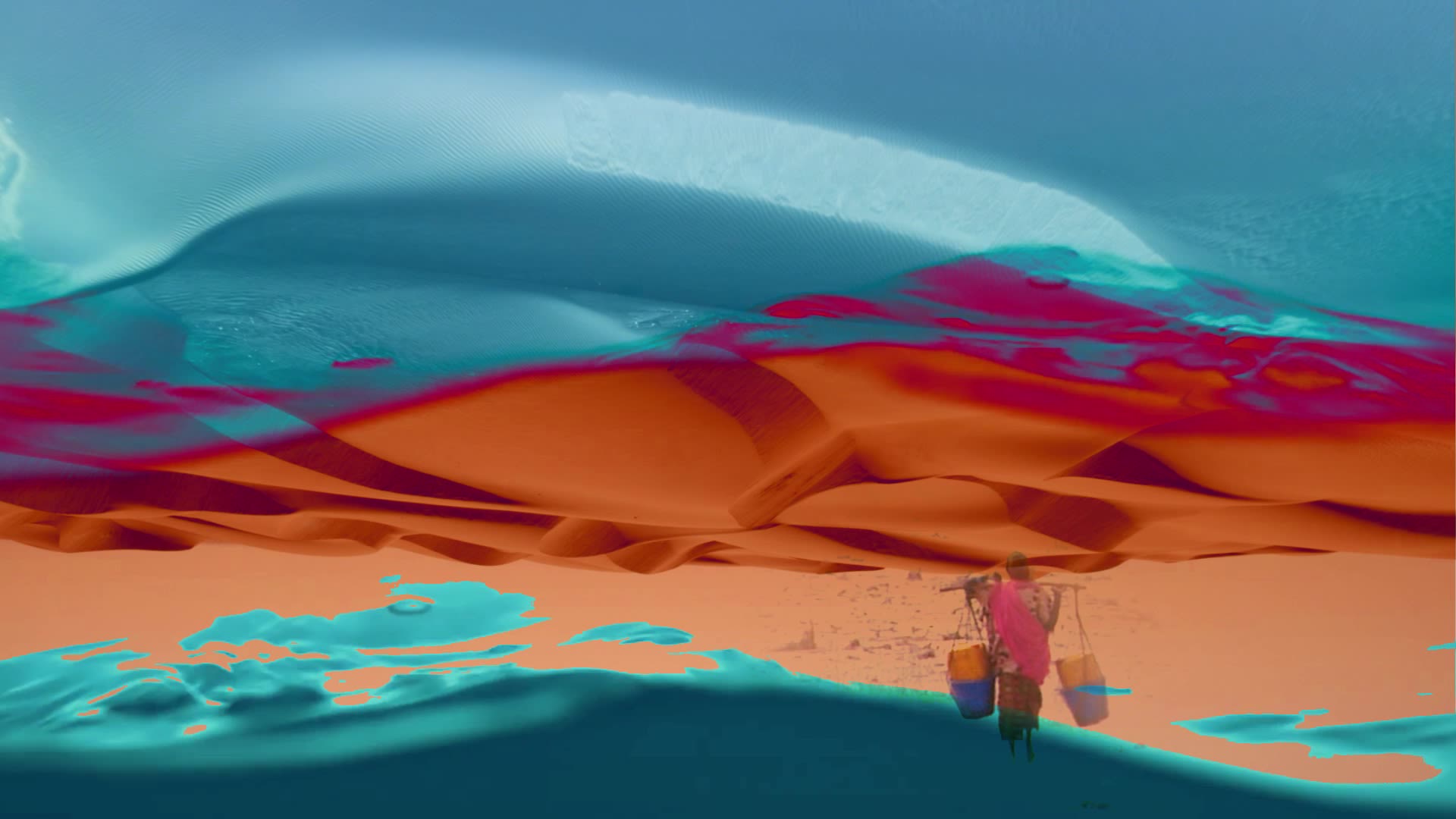

Yemen’s Houthis have announced they have “banned” vessels linked to Israel, the United States and United Kingdom from sailing in surrounding seas, as the rebels seek to reinforce their military campaign, which they say is in support of Palestinians in Gaza.

The Houthi’s Humanitarian Operations Coordination Center sent formal notices of the ban to shipping insurers and firms operating in the region on Thursday, the Reuters news agency quoted a statement as saying.

The Houthis’ communication, the first to the shipping industry outlining a formalised ban in the Red Sea, the Gulf of Aden and the Arabian Sea, came in the form of two notices, Reuters said.

It affects vessels wholly or partially owned by Israeli, American and British individuals or entities, as well as those sailing under their flags.

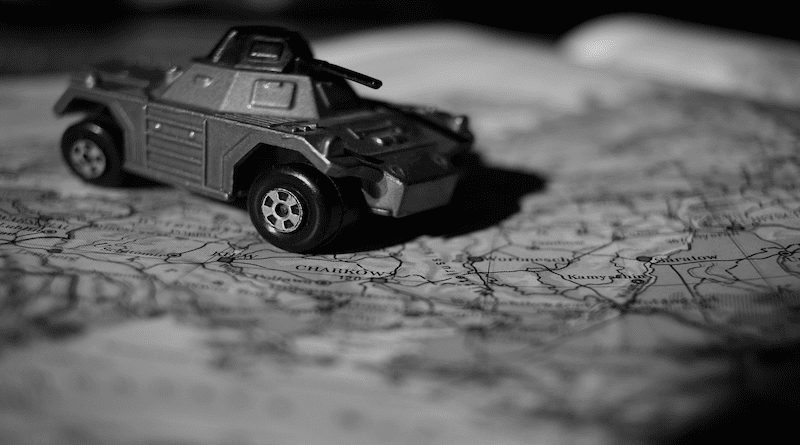

The warning came amid continuing Houthi attacks that have disrupted international trade on the shortest shipping route between Europe and Asia, and counterattacks by US and British forces hoping to deter the rebels.

They said the attacks were a response to Israel’s military operations in Gaza, which have killed almost 30,000 people in four months. They have promised to continue their campaign in solidarity with Palestinians until Israel stops the war.

On Thursday, Houthi leader Abdulmalik al-Houthi also said the group had introduced “submarine weapons” in their attacks.

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/archetype/YJR5QKCC2VGGTHMANNR3AADDJI.jpg)