The world is facing the worst five-year span in three decades. Higher interest rates have left developing countries crushed by debt, and half of the poorest economies haven’t recovered to where they were before the pandemic. Growth is weak across large swaths of the world, and inflation remains persistently high. And behind it all, the thermometer keeps inching up. Last year was the warmest on record, as is true of nearly every month.

For the last several years, world leaders have made big promises and laid out bold plans to mitigate the climate crisis and help poor countries adapt. They pledged that the World Bank would transform itself to work on climate change, and that the multilateral system would get new money and lend more aggressively with the resources it has, including to meet concessional needs. An agreement between creditors would provide debt relief to countries that most needed it. And where public money was insufficient, the multilateral system would be able to catalyze private investment in developing countries.

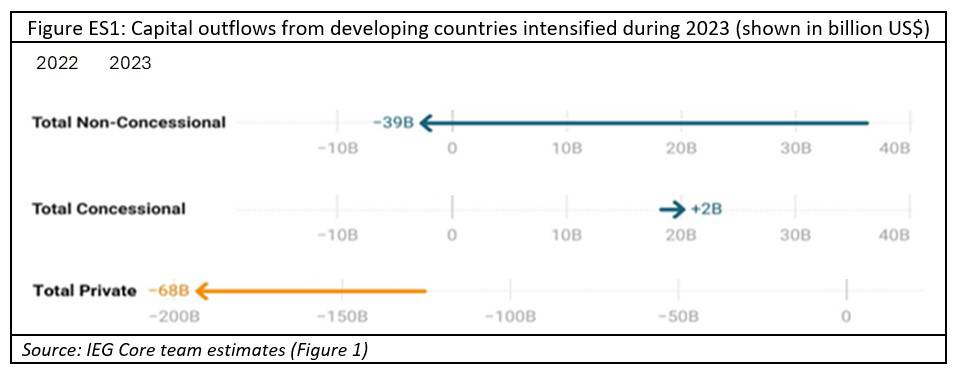

Despite the bold rhetoric, 2023 was a disaster in terms of support for the developing world. As the chart below demonstrates, the private sector collected $68 billion more in interest and principal repayments than it lent to the developing world. Amazingly, international financial institutions and assistance agencies withdrew another $40 billion, and net concessional assistance from international financial institutions was only $2 billion, even as famine spread. “Billions to trillions,” the catchphrase for the World Bank’s plan to mobilize private-sector money for development, has become “millions in, billions out.”

It is little wonder given that World Bank shareholders have not raised capital, substantially changed financing practices, or taken other bold steps. The International Monetary Fund is on net withdrawing funds from the developing world; the idea of comprehensive debt relief has gone nowhere; and financial defaults have been avoided only by the moral default of slashing health and education spending.

Setting aside the complex problem of climate change for a moment, world leaders haven’t even been able to tackle the simplest, most straightforward challenges. War, inflation, and poor governance have brought some of the poorest people – including in Chad, Haiti, Sudan, and Gaza – to the brink of famine, yet the international response has been slow and muted. This is both a humanitarian disaster in its own right and a symbol of our broader inability to act in the face of a crisis.

If the world can’t even get food to starving children, how can it come together to defeat climate change and reorient the global economy? And how can the poorest countries trust the international system not to leave them behind if that system can’t address the most basic challenges?

This week, finance ministers, central bankers, and economic leaders are gathering for the Spring Meetings of the World Bank and the IMF in Washington, DC, where they will discuss the global economy and lay out plans to strengthen it. But these efforts will fail if rhetoric falls as flat as it did during 2023 in terms of concrete action. Here are four big ideas as to what is necessary:

First, reverse the capital flows, so that the lowest-income countries are receiving more support than they are paying out to private creditors. In the short term, that means expanding the multilateral development banks’ use of innovative financial tools such as guarantees, risk-mitigation instruments, and hybrid capital. In the slightly longer term, it means stepping up with new money from shareholders – a capital increase for the World Bank and regional development banks, which will require legislative approval in shareholding countries.

Second, transform MDBs into big, risk-taking, climate-focused institutions. Development banks have tinkered around the edges with bolder approaches to lending, but it is time for them to scale up those efforts. The wealthy countries that are the biggest shareholders in the multilateral system need to provide the political support for that risk-taking.

Third, fully fund the International Development Association, a highly effective institution that provides much-needed resources to the lowest-income countries. The World Bank’s president has called for the largest-ever IDA replenishment from donors; given the challenges ahead, the world cannot afford to deliver anything less.

Fourth, tackle food security. Last year, the United Nations was able to raise from international donors only about one-third of what it sought for humanitarian relief, and it had to slash its goals for 2024. Stepping up with funding for the several hundred million people without enough food to eat would alleviate a humanitarian disaster and provide evidence to skeptical countries that the international system still can work.

Half the world goes to the polls this year, from the United States and the United Kingdom to India and Mexico. Pervasive distrust of governments and their promises is a ubiquitous issue, and we see every day that the idea of an international community is becoming an oxymoron. The conventional wisdom is that foreign policy falls by the wayside as politicians turn their focus to campaigning and to domestic issues that will win them votes.

We dare to hope that historians will look back at this week’s meetings as a moment when global leaders seriously addressed global challenges. The problem is not primarily intellectual. Blueprints like that of the G20 expert group we chaired on strengthening the MDB system abound. It is a problem of finding the political will to take on the most fundamental issues facing humanity.

No comments:

Post a Comment