Hui Zhang

On December 28, 1966, China successfully conducted its first hydrogen bomb test—only two years and two months after the successful explosion of its first atomic bomb. In so doing, China became the fastest among the five initial nuclear-weapon states (the United States, Russia, China, the United Kingdom, and France, collectively known as P5) to pass from its first atomic bomb explosion to a first hydrogen bomb detonation.

There is still very limited knowledge in Western literature about how China built its first H-bomb. Based on newly available information—including Chinese blogs, memoirs, and other publicly available publications—this account reconstructs the history of how China made a breakthrough in understanding hydrogen bomb principles and built its first H-bomb—without foreign help.

Beyond the previously untold story of China’s early exploration of the hydrogen bomb theory, the article also explores in detail the so-called “100 days in Shanghai”—a milestone of China’s hydrogen bomb development—and describes the efforts that led to a series of three nuclear tests that happened in 1966 and 1967 and that are often called “the trilogy” of the H-bomb development in China.

Early explorations

Raising the Little Red Book in celebration of China’s first atomic bomb test on October 16, 1964.

Moscow’s broken promise

China officially started its nuclear weapon program on January 15, 1955.[1] About two years later, China and the Soviet Union signed the New Defense Technical Accord in Moscow. Under that agreement, Moscow would provide Beijing with a prototype of an atomic bomb model and relevant technical materials. In June 1959, however, as many major relevant facilities in the Chinese nuclear weapon program were at the peak of construction, Soviet-Sino relations deteriorated,[2] and Moscow sent a letter to Beijing formally announcing it would not provide the promised model and data. From the second half of 1959 onward, the Second Ministry of Machine Building Industry—China’s government ministry overseeing the nuclear industry—followed central government policy and relied on the country’s own capabilities to complete the task of developing the atomic bomb.[3]

In early 1960, the weaponeers of the Beijing institute of nuclear weapon research—called the Ninth Institute and placed under the leadership of the Second Ministry[4]—started to explore atomic bomb science and technology. As those weaponeers started working hard on the atomic bomb program, then-Minister of the Second Ministry Liu Jie began considering ways to conduct the nation’s hydrogen bomb development. Before this, he had participated in the negotiation of the 1957 agreement with the Soviet government. In addition to information about the atomic bomb, under the agreement China was also supposed to receive a sample of a boosted nuclear bomb, specifically a “layer-cake” bomb.[5]

Liu understood that the boosted nuclear bomb provided by Moscow would be an atomic bomb, not a hydrogen bomb.[6] He sensed hydrogen bombs and atomic bombs could be very different in principle and structure. (An atomic bomb uses uranium or plutonium and relies on fission, a nuclear reaction that splits an atom or nucleus and releases a large amount of energy; a hydrogen bomb or H-bomb uses fission to trigger a fusion reaction that combines two atomic nuclei to form a single heavier nucleus, releasing a much larger amount of energy.) When the leader of the Soviet expert team was visiting the Second Ministry, Liu took the opportunity to ask him questions about the difference in principle and structure between the hydrogen bomb and the atomic bomb. But none of the responses he received satisfied him.[7] Liu understood that the Soviet Union would not share the hydrogen bomb technology with China. Liu therefore realized that it would take a significant amount of time to make breakthroughs in the theory of the hydrogen bomb and thought the start of this work could not wait until after the success of the first Chinese atomic bomb.

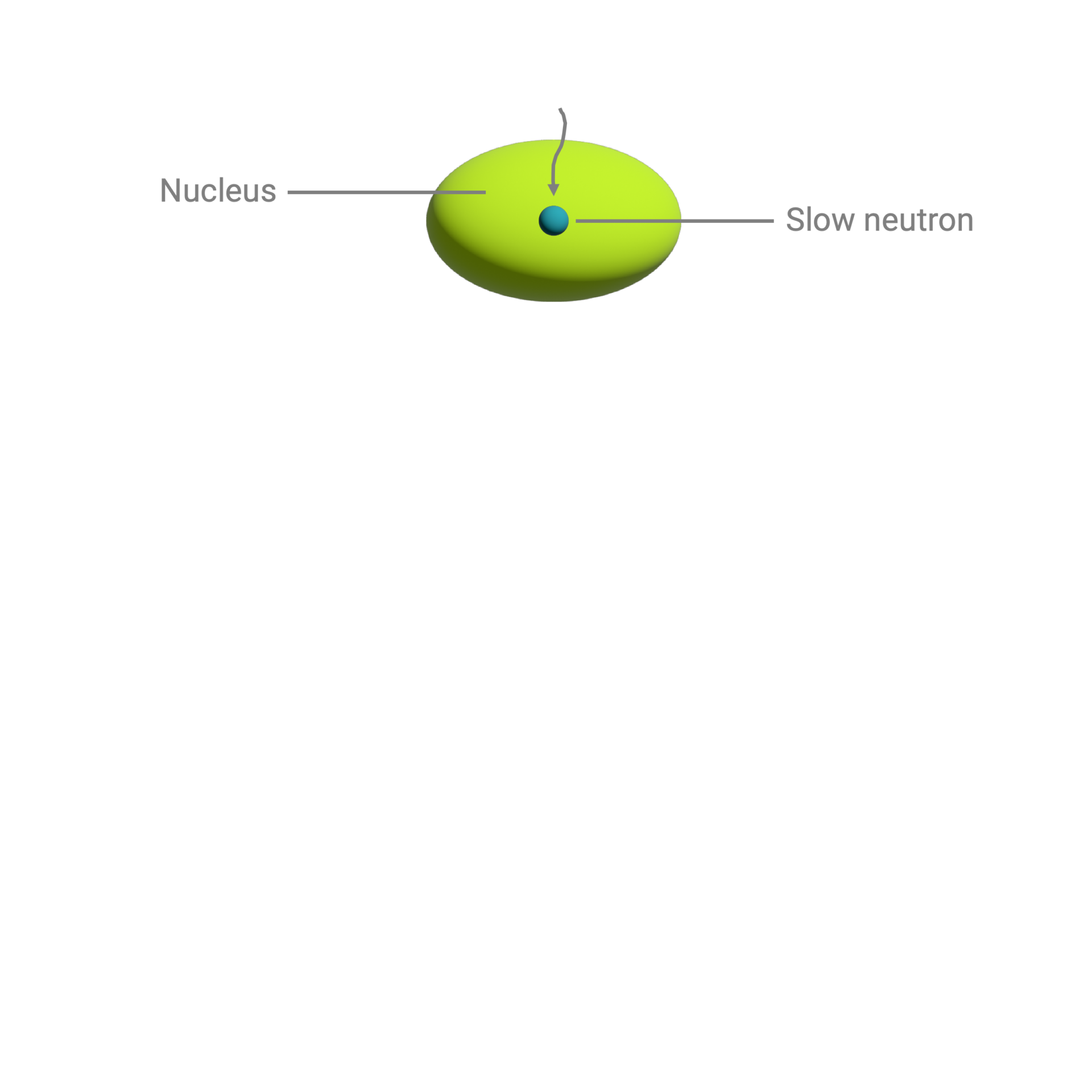

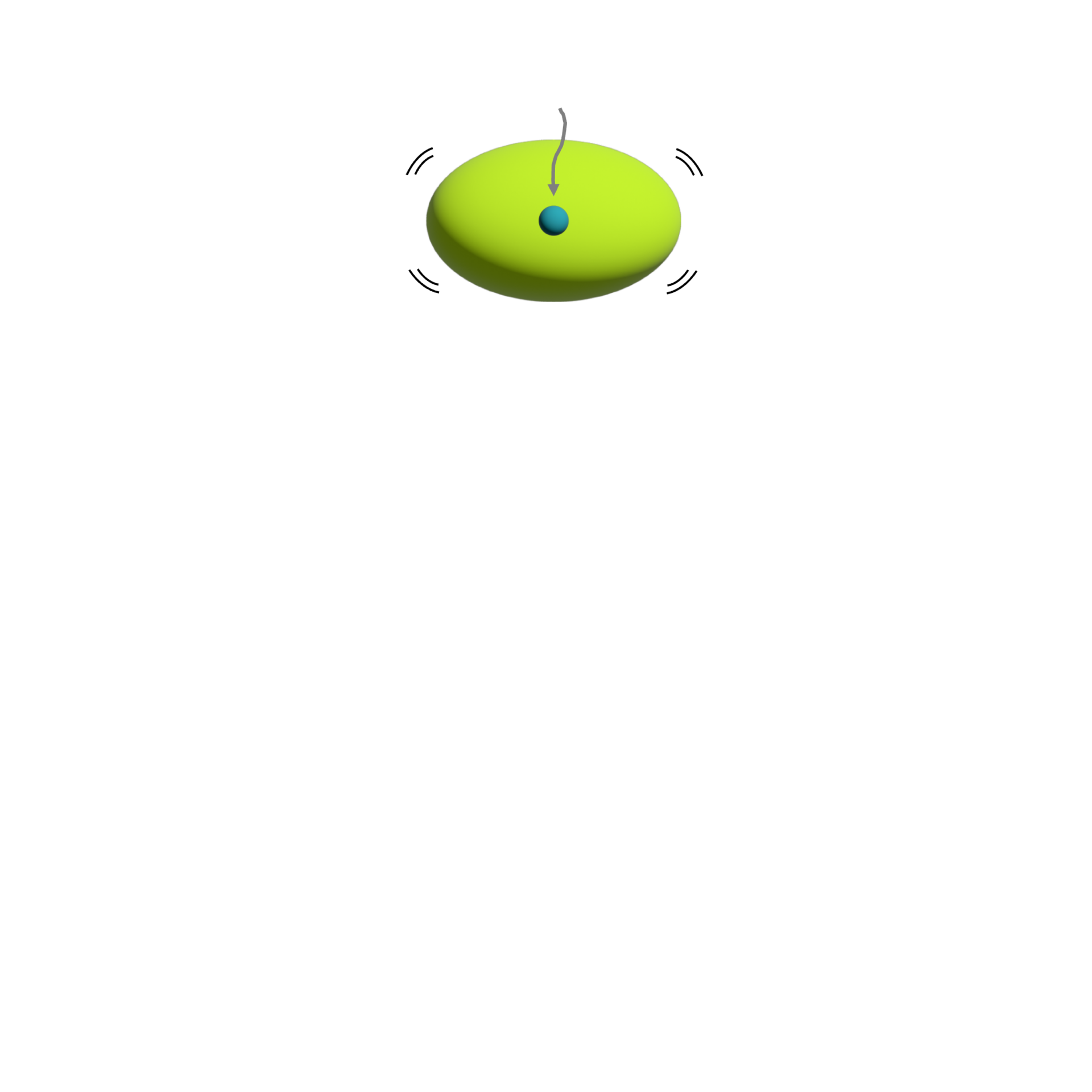

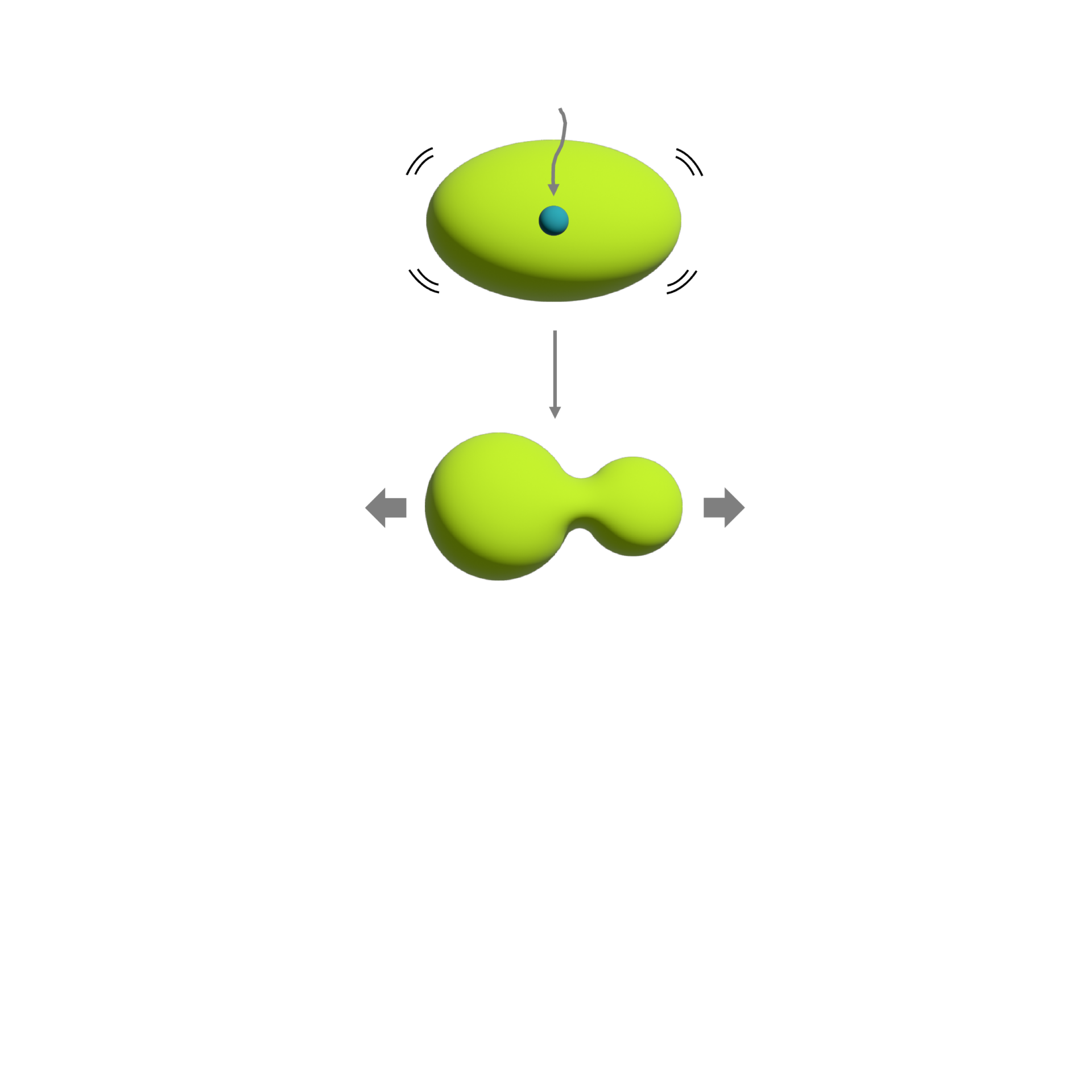

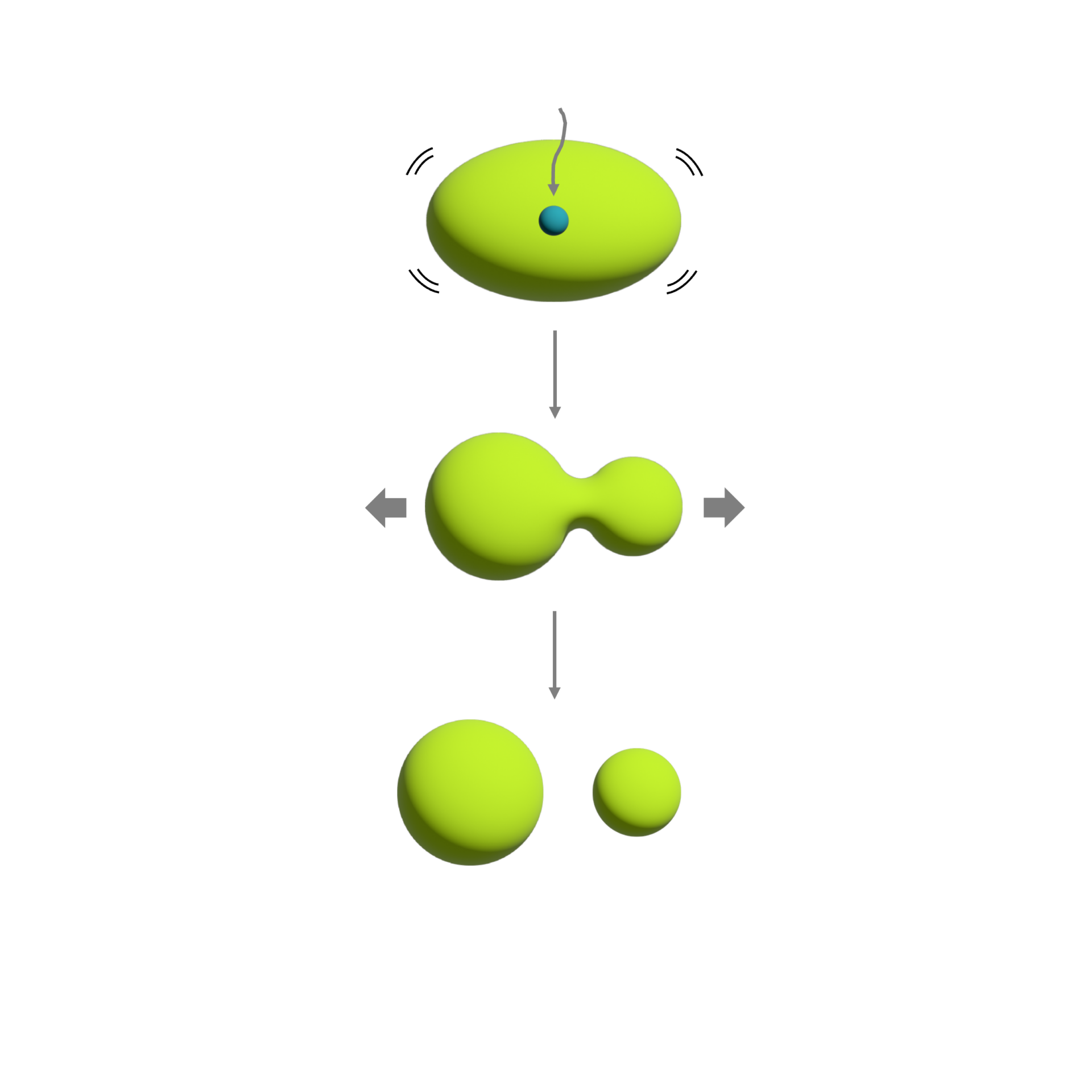

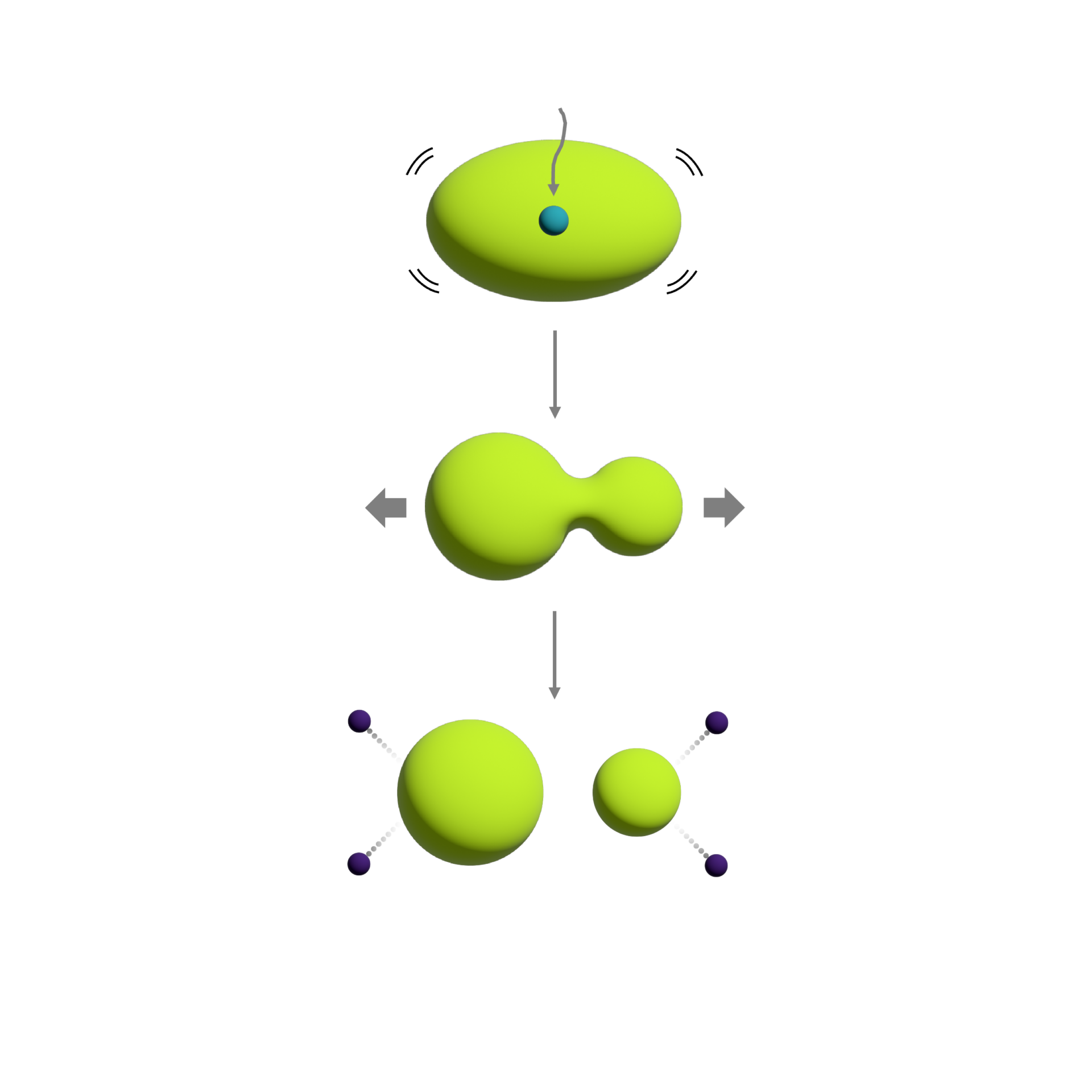

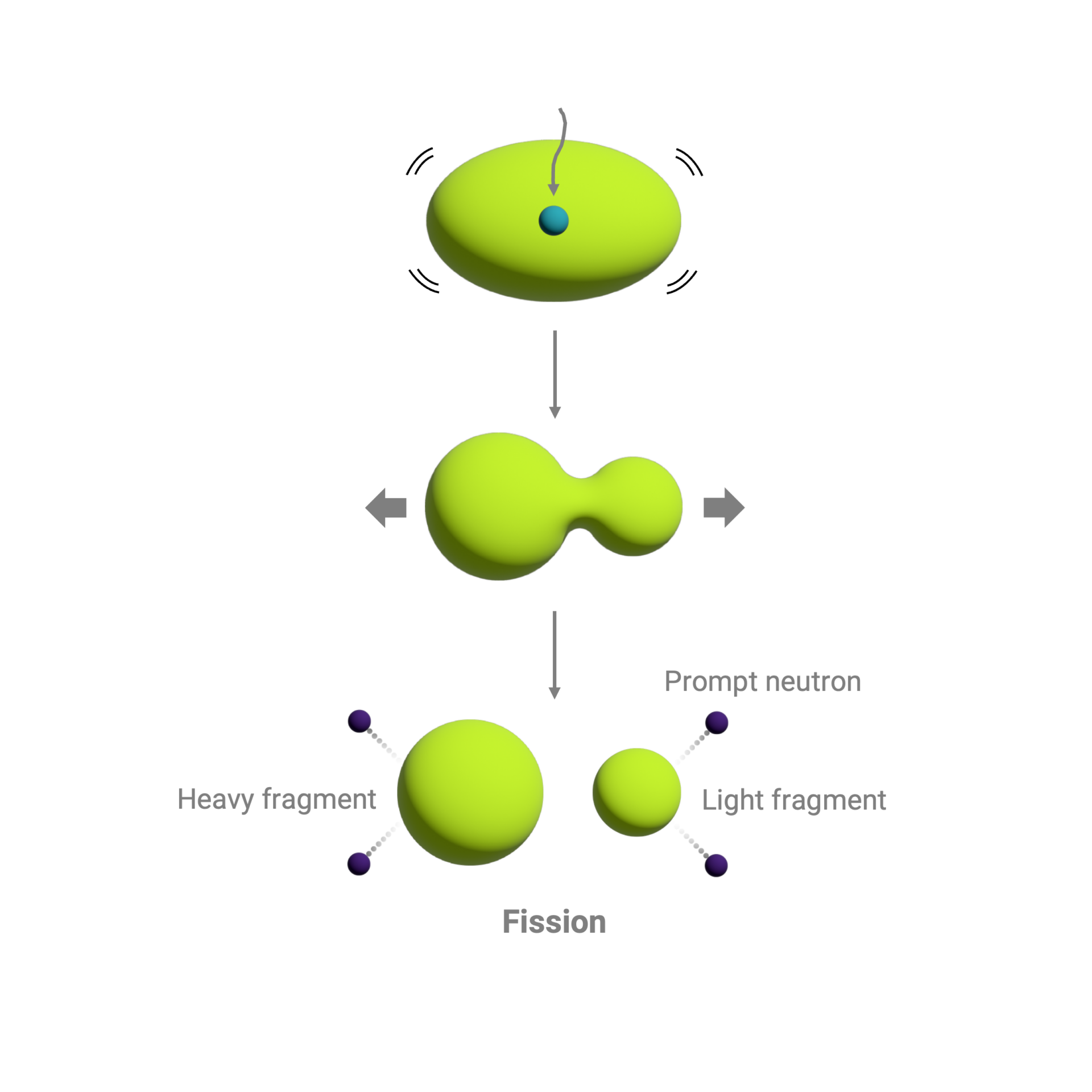

How nuclear fission worksBased on Bohr and Wheeler’s liquid drop model

When a positively charged nucleus absorbs a neutron …

… it vibrates …

… stretches …

… and splits.

The fission of the nucleus into two fragments releases a huge amount of energy in the form of excited (“prompt”) neutrons.

These neutrons can be captured by other nuclei and induce more fission events.

By modifying the arrangement and density of the fissile material, fission can proceed as a controlled, self-sustaining reaction or a “runaway” reaction that results in a nuclear explosion.

A new institute

Liu then discussed with Qian Sanqiang, then-Deputy Minister of the Second Ministry, the idea of launching a hydrogen bomb program. But because the weaponeers at the Ninth Institute were actively working to develop the first atomic bomb, and to avoid distracting their efforts, Qian agreed to set up a separate research force at the Institute of Atomic Energy (referred to as “Institute 401”) where he was serving as its director.[8] In December 1960, the deputy director of the Institute 401, Peng Huanwu, set up the “group of theory exploration on light nucleus reaction device,” referred to as the “Light Nucleus Theory Group.” In April 1961, Peng himself joined the Ninth Institute as its deputy director before taking the lead of the hydrogen bomb research program in 1963.[9]

In January 1961, Yu Min—a physicist who later would become known as “the father of China’s hydrogen bomb” and a leading figure in China’s overall nuclear weapons development—joined the Light Nucleus Theory Group, which gradually expanded to nearly 40 people. During four years of exploration and research, Yu Min and his group accomplished significant achievements in research on the physical process of the hydrogen bomb and made some preliminary explorations on the bomb’s principle. They also arrived at some preliminary assumptions about the possible overall structure of the bomb. All these research achievements laid essential foundations and would play an important role in the final breakthrough of the hydrogen bomb principle. The group merged with the Ninth Institute in January 1965.

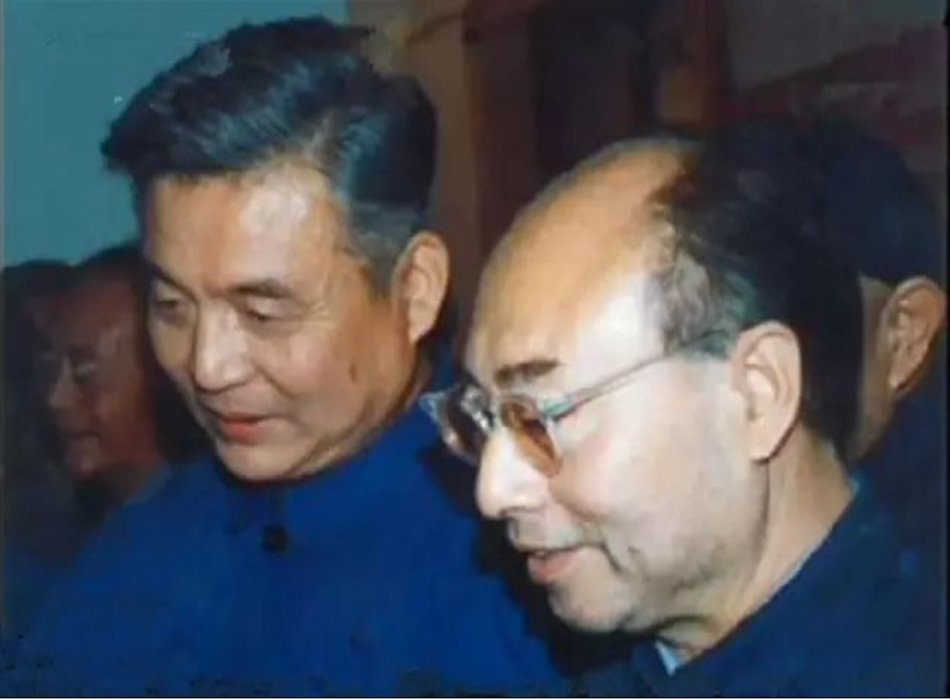

Deng Jiaxian (left) known as “the father of China’s atomic bomb” and Yu Min (right) known as “the father of China’s hydrogen bomb,” together. Undated.

A dead end

In March 1963, Deng Jiaxian, director of the theoretical division of the Ninth Institute, submitted the preliminary theoretical design of China’s first atomic bomb. Subsequently, part of his division moved on to explore hydrogen bomb theory. On September 3, 1963, after Marshal Nie Rongzhen examined the progress reports made by the leaders from the Second Ministry and Ninth Institute on the development of the first atomic bomb and plans for nuclear weapons, he declared that “after the detonation of the first atomic bomb, it is essential to quickly arrange the plans of the miniaturization of nuclear devices and the hydrogen bombs.”[10]

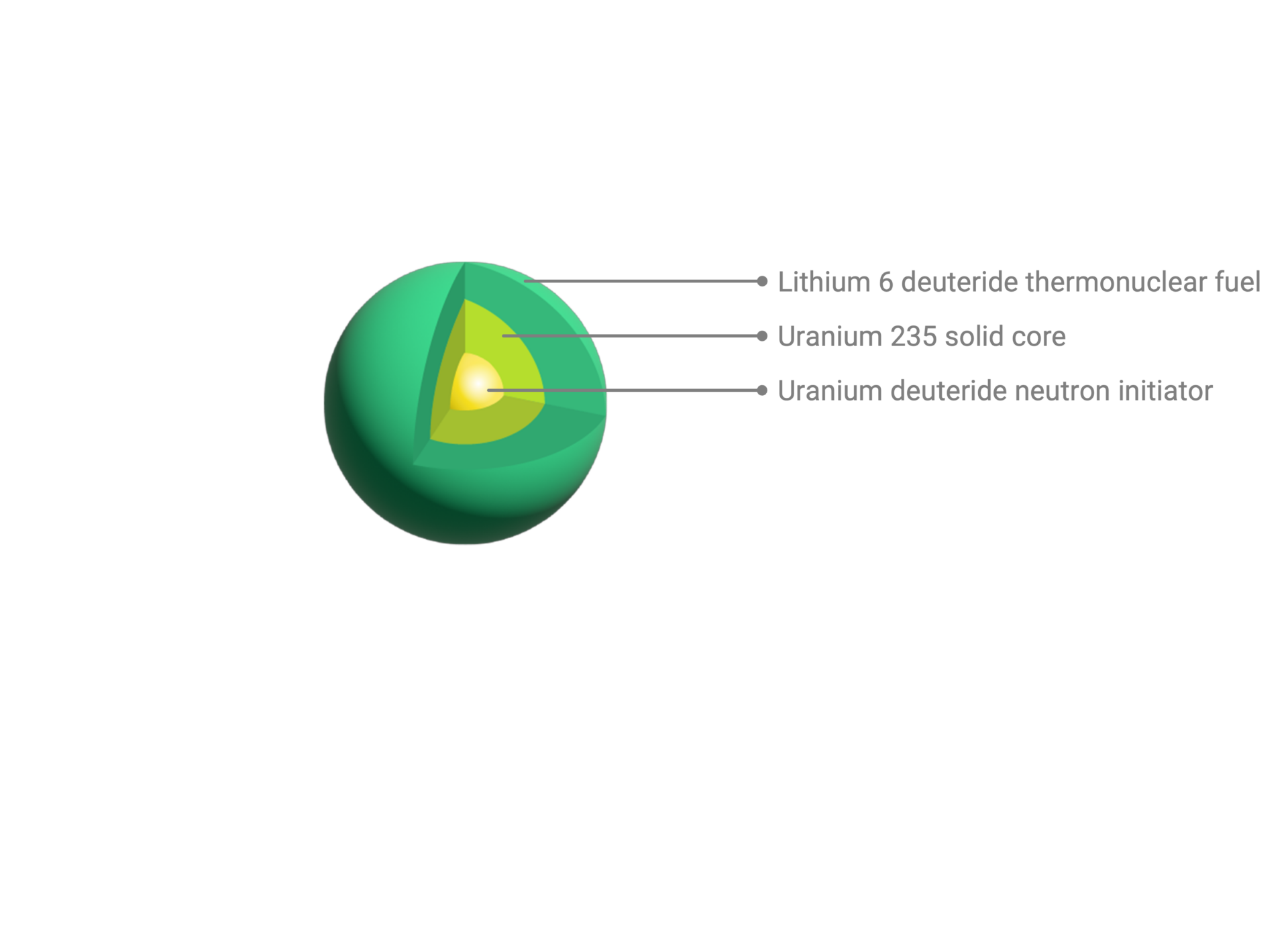

Once it had completed the theoretical design of the first atomic bomb, the Ninth Institute reinforced its “hydrogen bomb exploration group,” which was directed by Peng Huanwu.[11] The group started with the Soviet “layer-cake” model.[12] The model, however, was missing some data and Peng had to collect new information to complete it.[13] It is still unknown how Peng obtained the Soviet model, but there are several opportunities through which the design information of the model may have been disclosed—including through the 1957 agreement with Moscow or when Soviet experts helped to design the lithium deuteride production line at Baotou (Plant 212) to fuel the boosted atomic bomb in 1958.

The Soviet Union had tested only one layer-cake design bomb—the RDS-6 device, detonated on August 12, 1953.[14] After about a year studying the layer-cake model, Peng Huanwu and his group concluded that it was technically impossible to use the boosted atomic bomb design as a pathway toward the hydrogen bomb. The reason for this involved the boosted atomic bomb’s declining rate of chain reactions, which limited the increase in yield the device could deliver. To overcome this problem, the team proposed to study technical issues, including strong coupling of uranium and lithium deuteride. By May 1965, the group was now hoping that, by adding more uranium 235 to a devices, they could get a larger yield.[15]

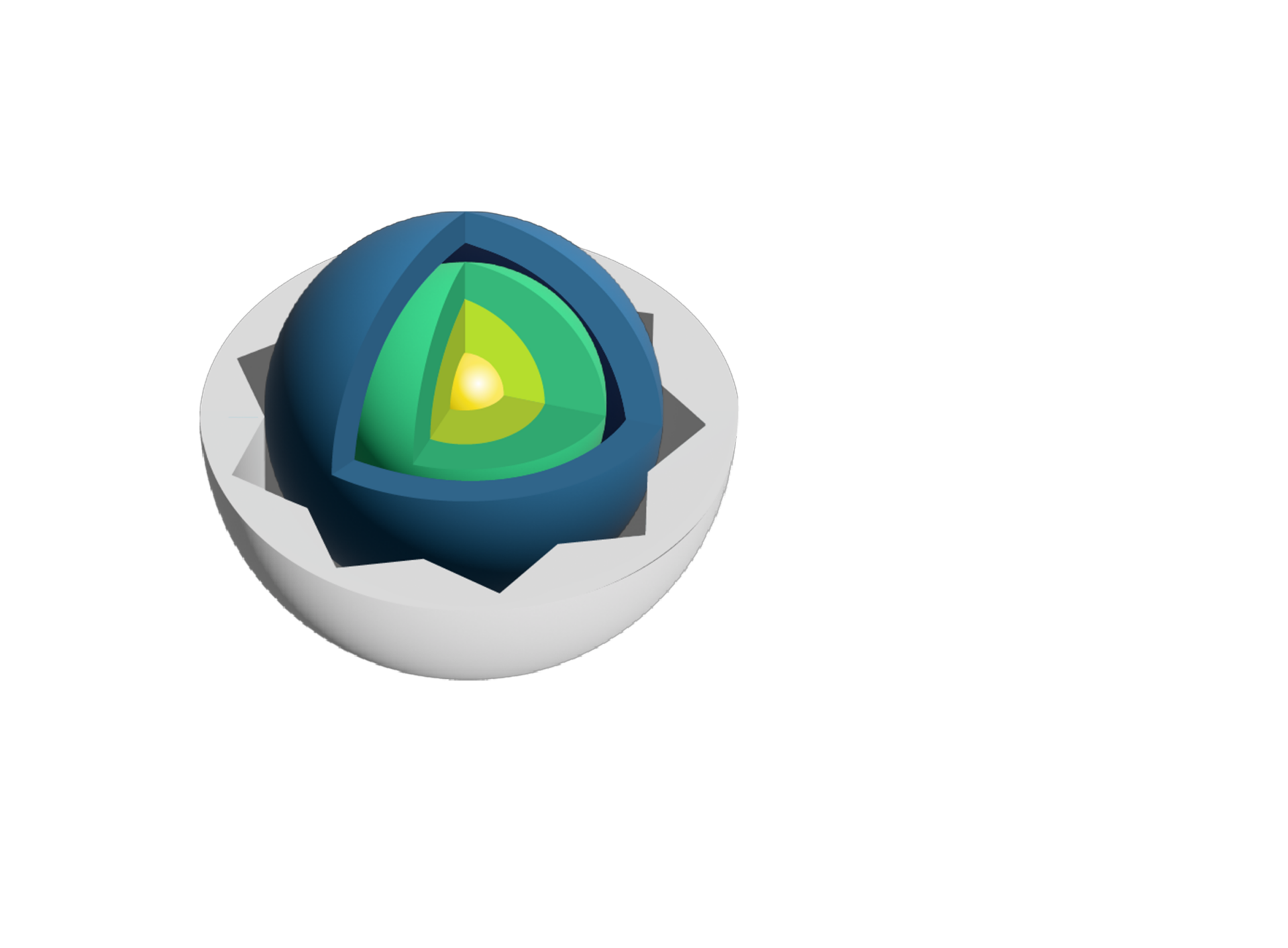

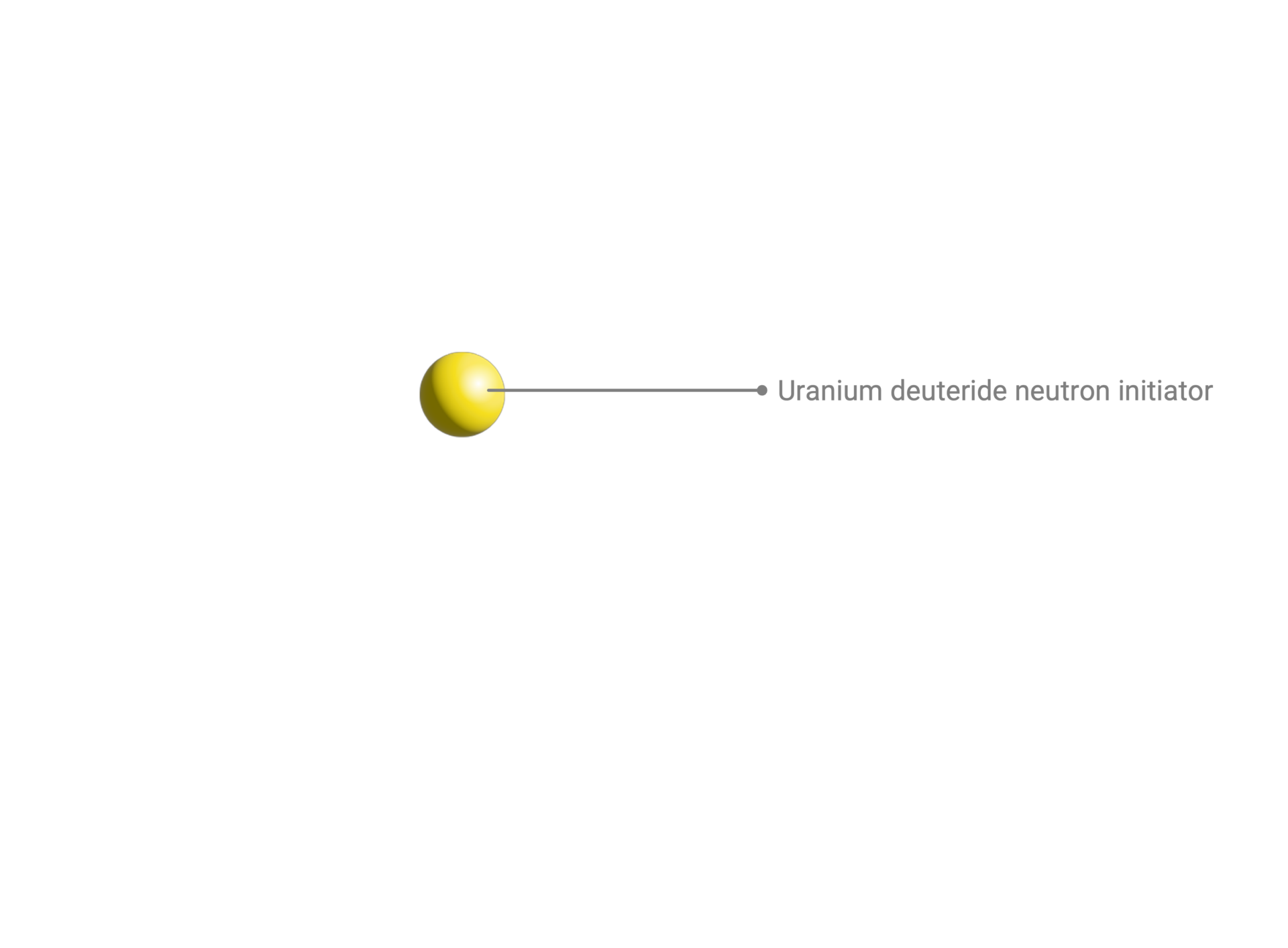

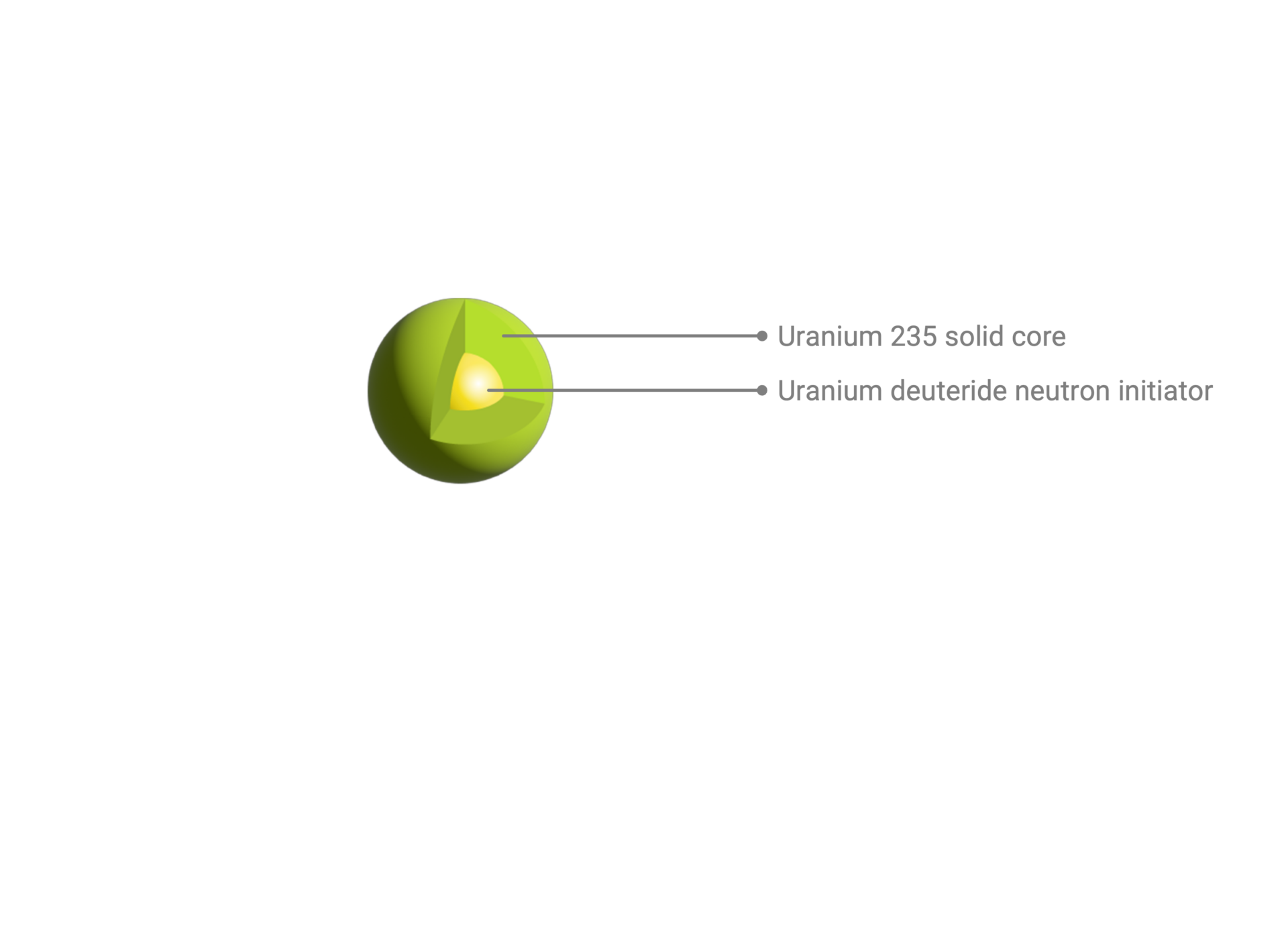

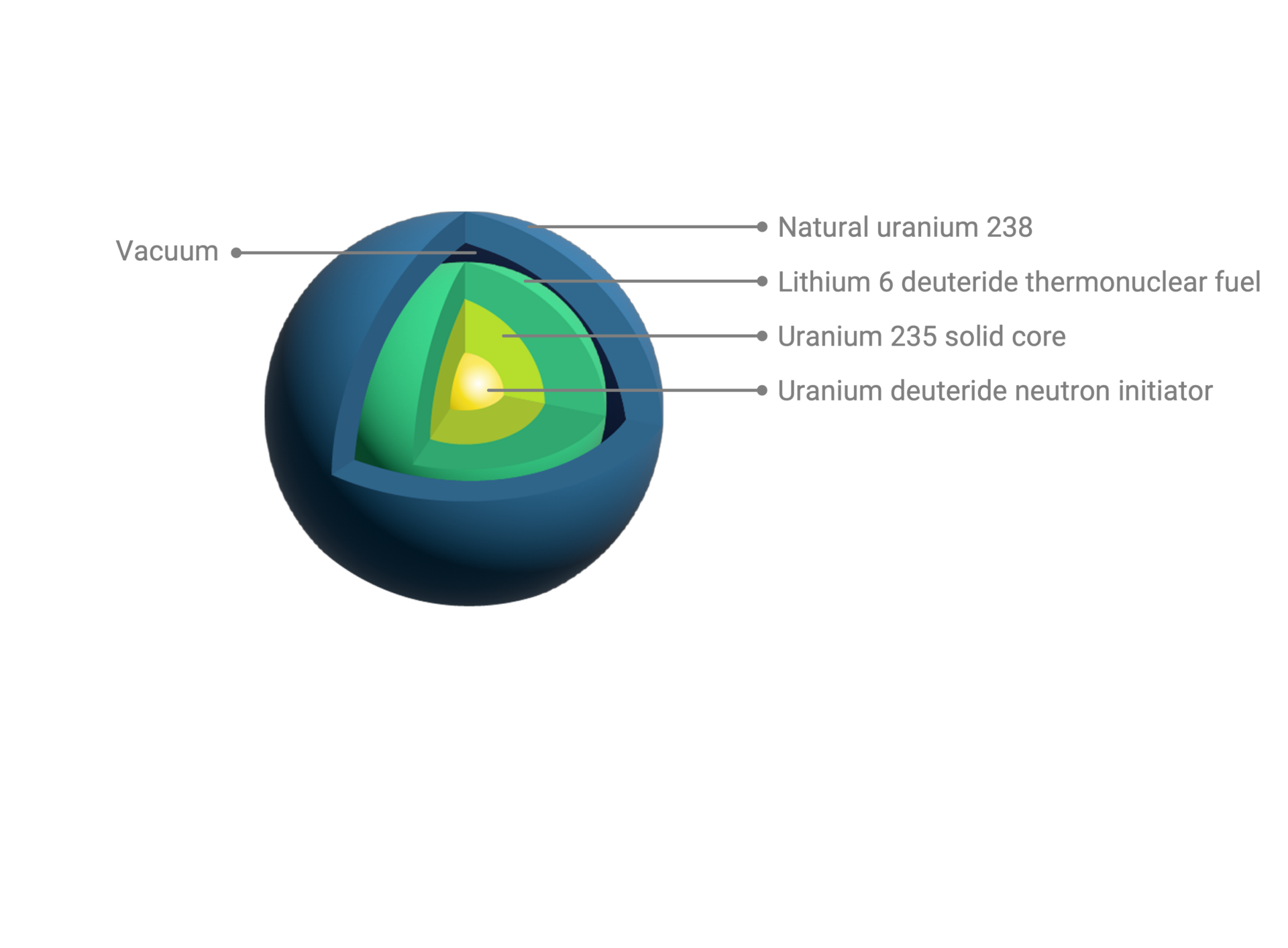

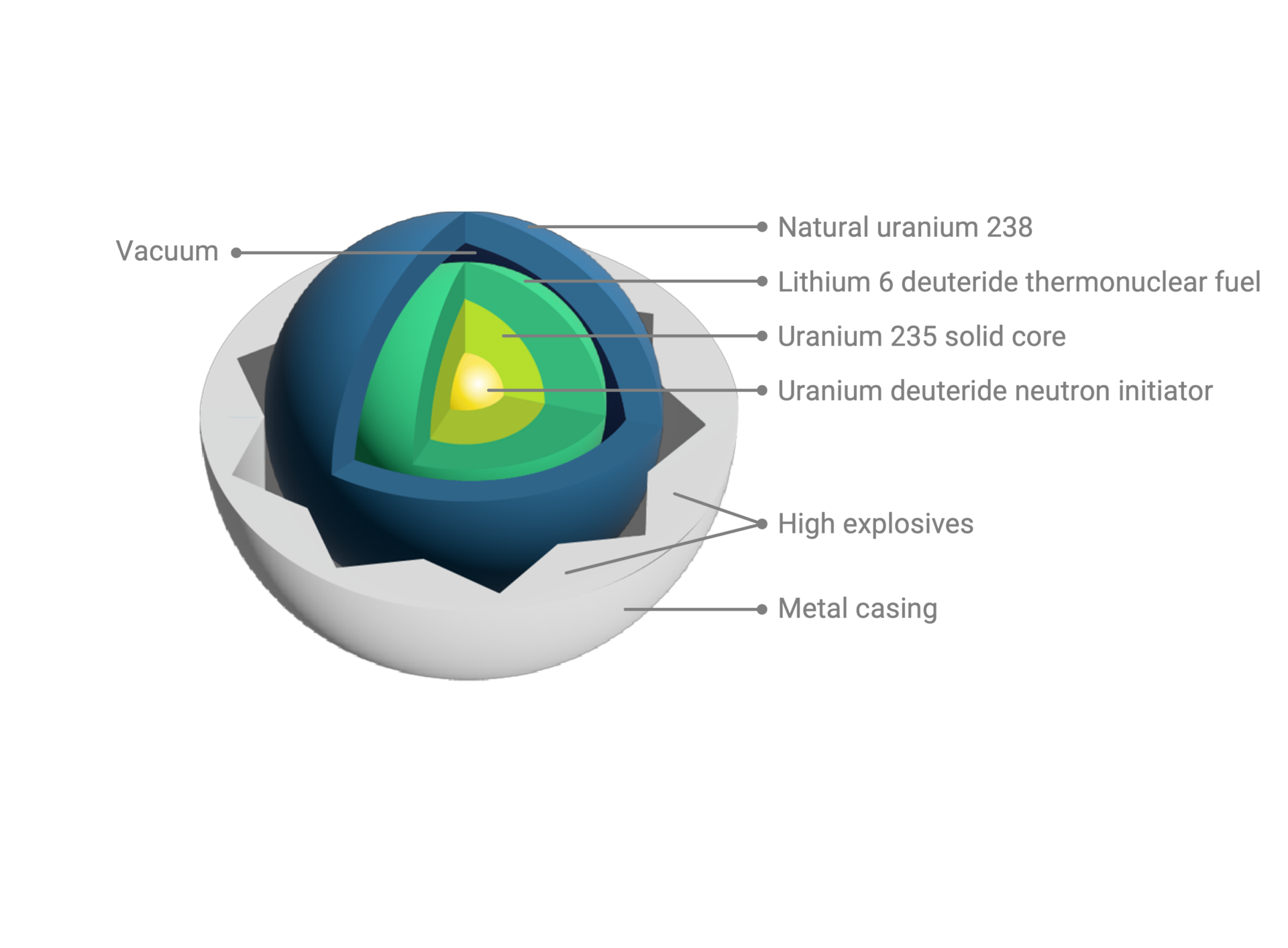

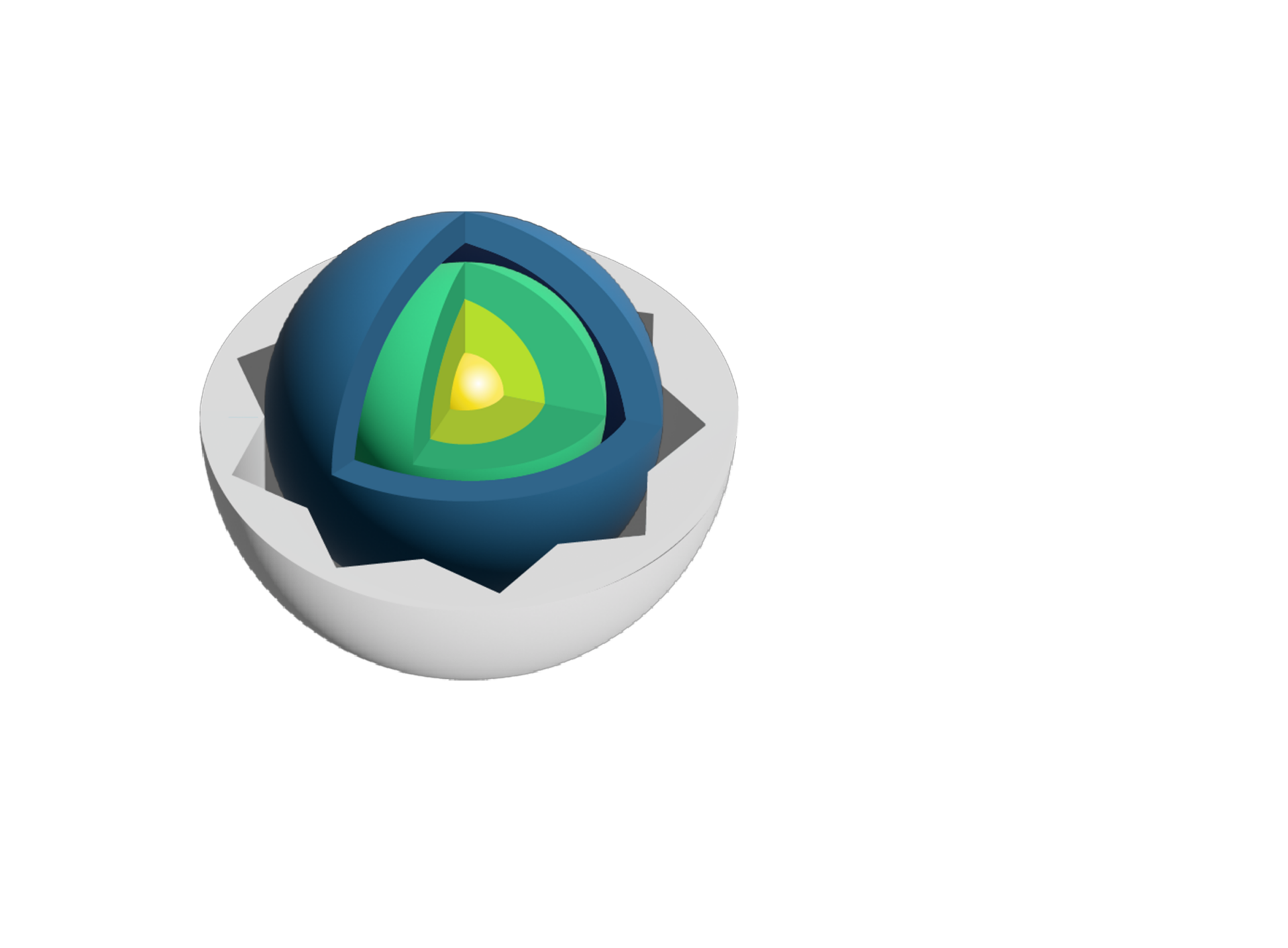

Boosted “layer-cake” implosion fission bomb design

Based on the first atomic bomb device 596 tested in October 1964

High explosives create shock waves that compress a uranium core until the nuclei split, releasing huge amounts of energy in a process called fission.

Starting over

On January 29, 1964, the Central Special Committee[16] reported to Mao Zedong—officially the Chairman of the Chinese Communist Party—and the Party’s Central Committee on the development of the atomic energy industry and the atomic bomb. The committee’s report proposed that “the central task of atomic energy for the Third Five-Year Plan (1966-1970) was to resolve the question of the ‘have or not’ of the nuclear bomb and thermonuclear bombs.”[17]

The development of the H-bomb started over—again.

Between 1964 and 1965, facing pressure from the central government to find a new pathway to the hydrogen bomb, the Ninth Academy (formerly known as the Ninth Institute) hosted discussions and debates on the topic and searched widely in the foreign scientific literature and news reports for any mention of the hydrogen bomb. At one workshop, Zhou Guangzhao, the deputy director of the academy’s theoretical division, brought a pile of magazines to show the participants that many photos of nuclear missiles had the shape of a long cylinder, instead of a large sphere as the layer-cake model suggested. Zhou believed the configurations of the atomic bomb and the hydrogen bomb were very different, and so their associated principles would also be different in nature.[18]

All the team could find was one sentence from a US newspaper that read: “Edward Teller’s brilliant idea that led to the creation of hydrogen bomb.”

The theoretical division subsequently set up a group to investigate US and Soviet newspapers and scientific papers on the subject. Those from the group went to the Beijing library to borrow all foreign newspapers, including all issues of the New York Times and Pravda since 1945. This effort required special permission from the Second Ministry because foreign newspapers were not available for public use at the time.[19] After loading those materials—reportedly in Jeeps—and bringing them back to the academy, the team started to read through all of them. All the team could find was one sentence from a US newspaper that read: “Edward Teller’s brilliant idea that led to the creation of hydrogen bomb.”[20] But, of course, the paper was not revealing what this “brilliant idea” actually was.

A goal code-named “1100”

On November 2, 1964, as they were discussing future nuclear testing issues, Premier Zhou asked his Minister Liu Jie when the hydrogen bomb would be ready. China had successfully conducted its first atomic bomb (device 596) test in October 1964.[21] Liu Jie replied that “the pre-research on the theory of the hydrogen bomb had been explored, and there were still many questions that cannot be fully understood. It will probably take three to five years.” Premier Zhou replied that five years were too many.[22] On January 7, 1965, Liu Jie delivered a speech at the meeting of the Second Ministry, conveying Mao’s new instructions to the audience: “If we have hydrogen bombs and missiles, wars may not be fought, and peace will be more secure. We make the atomic bombs but will not be too many. It will be used to scare [enemies] and embolden [ourselves].” Mao also said that “it still needs three years to have the hydrogen bomb, which is too slow.” [23]

In January 1965, the Second Ministry decided to transfer the Light Nuclear Theory Group of the Institute of Atomic Energy to the theoretical division of the Ninth Academy, as a way to speed up the development of the hydrogen bomb. By merging the two research forces, the ministry hoped to quickly resolve the key problems of hydrogen bomb development.[24] Yu Min was appointed deputy director of the now fleshed-out theoretical division.

On February 3, 1965, the Second Ministry set the goal of testing the first hydrogen bomb device in 1968.[25] When explaining the reasons why the ministry chose this target year, Liu Jie said that it would make China the fastest among the then-nuclear states to develop a hydrogen bomb from the first atomic bomb.[26] At the time, they defined a hydrogen bomb as one that had an explosive yield of more than one million tons of TNT equivalent, with fusion energy providing more than 30 percent of the yield. The next day, the Central Special Committee approved the Second Ministry’s proposal during a meeting presided by Premier Zhou.[27]

No comments:

Post a Comment