Graham Allison and Jonah Glick-Unterman

A quarter-century ago, China conducted what it called “missile tests” bracketing the island of Taiwan to deter it from a move toward independence by demonstrating that China could cut Taiwan’s ocean lifelines. In response, in a show of superiority that forced China to back down, the United States deployed two aircraft carriers to Taiwan’s adjacent waters. If China were to repeat the same missile tests today, it is highly unlikely that the United States would respond as it did in 1996. If U.S. carriers moved that close to the Chinese mainland now, they could be sunk by the DF-21 and DF-26 missiles that China has since developed and deployed.

This article presents three major theses concerning the military rivalry between China and the United States in this century. First, the era of U.S. military primacy is over: dead, buried, and gone—except in the minds of some political leaders and policy analysts who have not examined the hard facts.1 As former Secretary of Defense James Mattis put it starkly in his 2018 National Defense Strategy, “For decades the United States has enjoyed uncontested or dominant superiority in every operating domain. We could generally deploy our forces when we wanted, assemble them where we wanted, and operate how we wanted.”2 But that was then. “Today,” Mattis warned, “every domain is contested—air, land, sea, space, and cyberspace.”3 As a result, in the past two decades, the United States has been forced to retreat from a strategy based on primacy and dominance to one of deterrence. As President Joe Biden’s National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan and his National Security Council colleague Kurt Campbell acknowledged in 2019, “The United States must accept that military primacy will be difficult to restore, given the reach of China’s weapons, and instead focus on deterring China from interfering with its freedom of maneuver and from physically coercing U.S. allies and partners.”4 One of the architects of the Trump administration’s 2018 National Defense Strategy put it less diplomatically and more succinctly: “The era of untrammeled U.S. military superiority is over.”5

Second, while America’s position as a global military superpower remains unique—with power projection capabilities no one can match, more than 50 allies bound by collective defense arrangements, and a network of bases on almost every continent—both China and Russia are now serious military rivals and even peers in particular domains. Russia’s nuclear arsenal has long been recognized as essentially equivalent to America’s, and while China’s nuclear arsenal is much smaller, Beijing has nonetheless deployed a fleet of survivable nuclear forces sufficient to ensure mutually assured destruction. The Department of Defense (DOD) designation of China and Russia as Great Power competitors recognizes that they now have the power to deny U.S. dominance along their borders and in adjacent seas.

Third, if soon there is a “limited war” over Taiwan or along China’s periphery, the United States would likely lose—or have to choose between losing and stepping up the escalation ladder to a wider war. Deputy Secretary of Defense Kathleen Hicks and her fellow members of the National Defense Strategy Commission provided a vivid scenario of a war over Taiwan that the United States could lose.6 In response to a provocative move by Taiwan, or in a moment of hubris, if China were to launch a military attack to take control of Taiwan, it would likely succeed before the U.S. military could move enough assets into the region to matter. If the United States attempted to come to the defense of Taiwan with the forces currently in the area or that could arrive during the Chinese assault, it would not be able to materially affect the outcome.7 As former Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Admiral James Winnefeld and former Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) Acting Director Michael Morell wrote last year, China has the capability to deliver a fait accompli to Taiwan before Washington would be able to decide how to respond.8 The National Defense Strategy Commission reached a similar conclusion: the United States “might struggle to win, or perhaps lose, a war against China.”9

Beyond these findings, we begin with three further bottom lines up front:

- In 2000, anti-access/area-denial (A2/AD) systems—by which China could prevent U.S. military forces from operating at will—was just a People’s Liberation Army (PLA) acronym on a briefing chart. Today, China’s A2/AD operational reach encompasses the First Island Chain, which includes Taiwan (100 miles from mainland China) and U.S. military bases in Okinawa and South Korea (500 miles from mainland China). As a result, as President Barack Obama’s Under Secretary of Defense for Policy Michèle Flournoy put it, in this area, “the United States can no longer expect to quickly achieve air, space, or maritime superiority.”10 As former Commander of U.S. Indo-Pacific Command Admiral Philip Davidson testified to Congress in March 2021, on its current trajectory, in the next 4 years China’s A2/AD envelope will extend to the Second Island Chain, which includes America’s principal military installations on the U.S. territory of Guam (2,500 miles from mainland China).11

- No U.S. official has analyzed this issue more assiduously than Robert Work, who served as Deputy Secretary of Defense under three secretaries before stepping down in 2017. While the acid test of military forces is their performance in combat, the next best indicator is wargames. As Work has stated publicly, in the most realistic wargames the Pentagon has been able to design simulating war over Taiwan, the score is 18 to 0. And the 18 is not Team USA. Reporting on an Air Force wargame conducted last fall documented a different outcome: the U.S. military successfully repelled a Chinese invasion of Taiwan, but doing so required fielding systems that it does not yet have, that are not in production, and that are not even planned for development, in addition to undertaking major structural reforms and convincing Taiwan to multiply its defense spending.12 These findings are—and should be—cause for alarm since Taiwan is the most likely source of military conflict between China and the United States.13 As Admiral Davidson warned in March 2021, the risk of conflict over Taiwan is “manifest during this decade.”14

- In the words of Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Mark Milley, when “all the cards are put on the table,” the United States no longer dwarfs China in defense spending.15 In 1996, China’s reported defense budget was 1/30 the size of America’s. By 2020, China’s declared defense spending was one-quarter ours. Adjusted to include spending on military research and development and other under-reported items, it approached one-third of U.S. spending. And when measured by the yardstick that both the CIA and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) judge the best single metric for comparing national economies, it is over one-half U.S. spending and on a path to parity.16 Moreover, while the U.S. defense budget buys weapons and builds forces to sustain America’s unique global presence, which includes commitments on almost every continent, China’s defense budget is focused locally on preparing for contingencies in Northeast Asia.

Given the secrecy that surrounds some aspects of this topic, the clamor of advocates seeking to persuade Congress to fund their budgets, and a press that tends to hype the China threat, it is often difficult to assess the realities. Because so many of the public claims are misleading, this article does not address the U.S.-China cyber rivalry. Nonetheless, by focusing on the hard facts that are publicly available about most of the races and listening carefully to the best expert judgments about them, in the military rivalry with China, the United States has entered a grave new world.17

Should recognition of ugly military realities in this new world be cause for alarm? Yes. But the path between realistic recognition of the facts, on the one hand, and alarmist hype, on the other, is narrow. Moreover, in the current climate, with American political dynamics fueling increasing hostility toward China, some have argued that talking publicly about such inconvenient truths could reveal secrets or even encourage an adversary. But as former U.S. military and civilian Defense Department leaders have observed, China’s leaders are more aware of these brute facts than are most members of the American political class and policy community. Members of Congress, political leaders, and thought leaders have not kept up with the pace of change and continue repeating claims that may have made sense in a period of American primacy but that are dangerously unrealistic today. As a few retired senior military officers have stated pointedly, ignorance of military realities has been a source of many civilians’ enthusiasm for sending U.S. troops into recent winless wars.

The Rise of a Peer

America’s demonstration of overwhelming military superiority in 1996 left China no option but to back down in its own backyard. But this vivid reminder of China’s “century of humiliation” also steeled Chinese leaders’ determination to build up Beijing’s military strength to ensure this could never happen again.

In the years since, as the 2020 DOD annual report on China described, the People’s Republic of China has “marshalled the resources, technology, and political will…to strengthen and modernize the PLA in nearly every respect.”18 Indeed, the overall balance of conventional military power along China’s borders has shifted dramatically in China’s favor. In Admiral Davidson’s careful understatement, there is “no guarantee” of victory in a conflict against China.19

This shift in the balance of power follows PLA reforms that are unprecedented in depth and scale. In November 2015, Xi Jinping directed the most extensive restructuring of the PLA in a generation for China to have a military that is, in his words, “able to fight and win wars.”20 Under a Central Military Commission chaired by Xi, the PLA created five joint theater commands and established the Joint Logistics Support Force and the Strategic Support Force, which is responsible for high-technology missions. In addressing the 19th Party Congress in 2017, Xi proclaimed the PLA’s objectives to become a fully “mechanized” force by 2020, a fully “modernized” force by 2035, and a “world-class” force by 2049.21

These reforms have been tailored to reinforce PLA loyalty to the Chinese Communist Party and specifically to Xi as its chairman and to align China’s military power with its national ambitions. In Xi’s words, achieving the “great revival of the Chinese nation” requires “unison between a prosperous country and strong military.” The “Strong Army Dream” and its mandate to be able to “fight and win” are foundational to the “China Dream.”22

A modernized PLA will enable Beijing to deter third-party interventions, conduct regional missions, and protect China’s extra-regional interests. Deterring and defeating threats to China’s sovereignty are its armed forces’ highest priorities. As Xi declared at the 19th Party Congress, “We will never allow anyone, any organization, or any political party, at any time or in any form, to separate any part of Chinese territory from China!”23 Indeed, China has done everything it can to communicate unambiguously that, to prevent the loss of Taiwan, it is prepared to go to war—even though it recognizes that war with the United States risks escalation to nuclear war.

As a reminder of China’s willingness to go to war for what it sees as its core interests, Americans should never forget what happened in Korea. As American troops approached China’s border, even though it had only a peasant army, many of whom did not even have shoes, Beijing nonetheless attacked the world’s sole superpower. After the United States came to the rescue of South Korea when it was attacked by North Korea, as U.S. troops moved up the peninsula rapidly toward the Yalu River, which marks the border between North Korea and China, they discounted warnings that China might intervene on behalf of the North. The possibility that a poor country still consolidating control of its own territory after a long civil war would attack the world’s most powerful military, which had just 5 years earlier dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki to end World War II, seemed inconceivable. But Mao Zedong did just that. In late October 1950, Douglas MacArthur woke to find a vanguard of 300,000 Chinese troops slamming U.S. and allied forces. In the weeks that followed, Mao’s forces not only halted the allied advance but also beat United Nations (UN) forces back to the 38th Parallel.24

The Tyranny of Distance

Geography matters. Military planners talk about the “tyranny of distance.” As illustrated in figure 1, to support conflict along China’s borders and in its adjacent seas, U.S. ships must travel for multiple days or weeks. This unalterable asymmetry is a key driver behind China’s A2/AD strategy, whereby China has built capabilities on its own mainland and shifted the military balance in potential conflicts over Taiwan or in the South and East China seas.

Figure 1.

A critical component of these capabilities is the PLA’s arsenal of intermediate-range missiles. Having elevated the PLA Rocket Force to an independent service in 2015, Beijing has amassed what the U.S. Air Force judges “the most active and diverse ballistic missile development program in the world.”25 China has more than 1,250 ground-launched ballistic and cruise missiles with ranges between 500 and 5,500 kilometers, while the United States fields only one type of conventional ground-launched ballistic missile with a range of 70 to 300 kilometers and no ground-launched cruise missiles.26 In 2020, the PLA launched more ballistic missiles for testing and training than the rest of the world combined.27 Most prominent, the PLA Rocket Force developed and tested the DF-21 and DF-26 medium-range ballistic missiles, which have been dubbed “carrier-killers,” to credibly threaten America’s most prized power projection platform.28

The PLA Rocket Force’s vast stocks of conventional guided munitions underwrite what U.S. strategists have called a “projectile-centric strategy.”29 Projectiles are cheaper than air forces, easier to mass in a salvo exchange than airborne-based strikes, and harder to hunt than fixed airbases. In a conflict, they can penetrate U.S. forward defenses and cripple key nodes in U.S. battle networks while outranging reinforcements surging to the theater.30 As leading RAND analyst James Dobbins and other RAND researchers have explained, “the range and capabilities of Chinese air and sea defenses have continued to grow, making U.S. forward-basing more vulnerable and the direct defense of U.S. interests in the region potentially more costly.”31

No longer can the United States rely on nuclear escalation dominance, either. In 2000, China had a “minimum deterrent” strategy underwritten by only a few hundred nuclear warheads and a handful of intercontinental ballistic missiles that could reliably reach the American homeland to destroy American cities.32 Moreover, these missiles were vulnerable to a preemptive U.S. nuclear first strike. Today, according to Pentagon estimates, China still has a modest arsenal, with warhead numbers in the low 200s—less than 5 percent of America’s 5,500 warheads.33 Nonetheless, Beijing has concluded that this force is sufficient to ensure that it would survive an American first strike and be able to retaliate with a counterstrike that could destroy enough of the United States to create a nuclear stalemate. Both sides’ entrenchment in a state of mutually assured destruction will only deepen if China expands its nuclear arsenal to 700 deliverable warheads by 2027, as the Pentagon anticipates.34

The United States has recognized this reality in sizing its own missile defense systems. As the Obama administration’s 2010 Ballistic Missile Defense Review Report determined:

Russia and China have the capabilities to conduct a large-scale ballistic missile attack on the territory of the United States. . . . While the [ground-based midcourse defense] system would be employed to defend the United States against limited missile launches from any source, it does not have the capacity to cope with large scale Russian or Chinese missile attacks.35

Thus, if Ronald Reagan was right when he declared that “a nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought,” then between these nuclear superpowers (that is, nations with robust, reliable second-strike capabilities), the menu of viable military options cannot include nuclear attack.36

Wargames: A Perfect Record

The acid test of military forces is how they perform in combat. Short of that, wargames provide the next best indicator. U.S.-China wargames in plausible conflict scenarios offer a discouraging operational picture of the local balance of power. Most of these games are classified, and the most significant the most highly so. Particularly when the results are not favorable for Blue (Team USA), they are rarely publicized. Yet one of the features of the American system is that former officials sometimes speak candidly after they leave government. As Senator John McCain’s former Senate Armed Services Committee Staff Director Christian Brose has stated bluntly, “Over the past decade, in U.S. wargames against China, the United States has a nearly perfect record: We have lost almost every single time.”37

American strategists have been stunned by this scorecard and its operational implications. Summarizing a recent series of wargames, former defense planner David Ochmanek observed that, when we fight China, “Blue gets its ass handed to it.”38 Ochmanek noted that “For years the Blue Team has been in shock because they didn’t realize how badly off they were in a confrontation with China.”39 Former Deputy Secretary Work similarly found that “whenever we have an exercise, and when the Red Force really kind of destroys our command and control, we stop the exercise and say, ‘Okay, let’s restart. And, Red, don’t be so bad.’”40

In the wargames, U.S. forces struggle to achieve superiority in key operating domains early in a conflict. According to Ochmanek, “all five domains of warfare are contested from the outset of hostilities.”41 Likewise, as Work observed, “In the first five days of the campaign, we are looking good. After the second five days, it’s not looking so hot. That is what the war games show over and over and over.”42 Moreover, U.S. forces incur substantial losses of platforms and personnel. “We lose a lot of people,” Ochmanek acknowledged. “We lose a lot of equipment,” he continued.43 U.S. forward-deployed forces, including airbases in Okinawa and Guam, surface ships, non-stealthy aircraft, and other exposed U.S. assets proximate to the battlespace, suffer early and persistent salvos of conventional precision munitions.44 In Brose’s summary, “The command and control networks that manage the flow of critical information to U.S. forces in combat would be broken apart and shattered by electronic attacks, cyber attacks, and missiles. Many U.S. forces in combat would be rendered deaf, dumb, and blind.”45

The U.S. military has had extensive recent combat experience, but much of it is not that helpful for preparing to meet a peer competitor. As Deputy SecretaryWork has explained, in those campaigns the local balance of power at the outset of conflict “didn’t really matter. . . . We would’ve crushed them like cockroaches once we assembled the might of America.”46 But a conflict with China today would be different. As Brose concluded, a war over Taiwan “could be lost in a matter of hours or days even as the United States planned to spend weeks and months moving into position to fight.”47

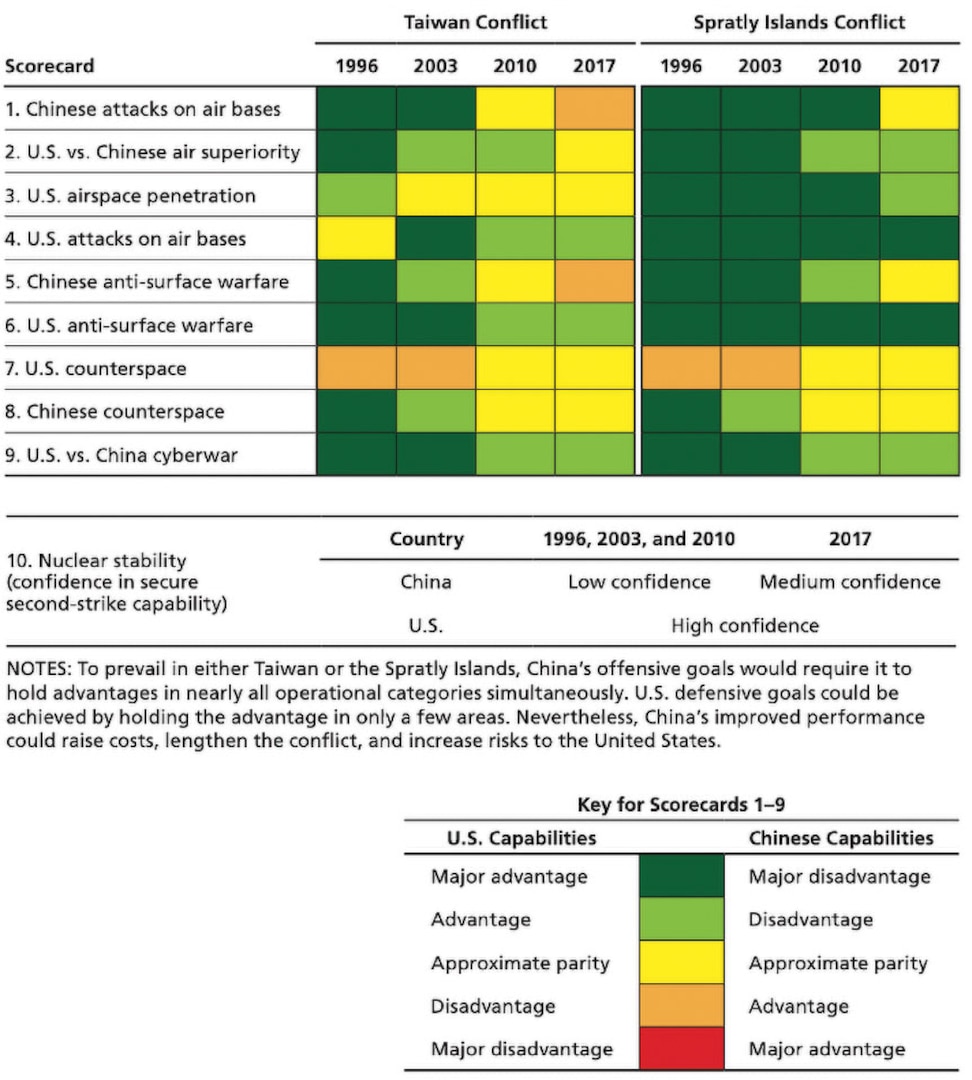

These uncomfortable findings are supported by the most authoritative public assessment of the operational balance, RAND’s “U.S.-China Military Scorecard.” It determined that, in a conflict over Taiwan, China would enjoy the advantage in U.S. airbase attack and anti-surface warfare. It would have approximate parity in establishing air superiority, penetrating U.S. airspace, and conducting and defending against counterspace operations. As the report concluded, with the United States no longer enjoying major advantages in nine key operational dimensions, “Asia will witness a progressively receding frontier of U.S. dominance.”48

Of course, there are choices the United States could make that would lead to changes on this scorecard in the years ahead. One that has been highlighted by Admiral Winnefeld would be to develop new high-power microwave weapons for disrupting electronics using electromagnetic energy.49 But these choices have not yet been made.

Future Technologies

China is laser-focused on military applications of emerging technologies, including artificial intelligence (AI), quantum computing, hypersonic missiles, and space assets. As former Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Paul Selva warned in 2018, on the current path, the United States will lose its technological superiority around 2020, and China will surpass the United States by the 2030s.50

In the decades since the shock and awe demonstrated by U.S. guided munitions warfare in Operation Desert Storm, China has pursued what former Deputy Secretary Work has aptly called an “offset strategy with Chinese characteristics.” As he describes it, Beijing has undertaken a “patient, exquisitely targeted, and robustly resourced technologically driven offset strategy” to achieve technological parity and, ultimately, superiority.51

Chinese strategists believe AI may be decisive in Beijing’s campaign to surpass the United States as the world’s premier military power.52 Former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Joseph Dunford concurred, “Whoever has the competitive advantage in artificial intelligence and can field systems informed by artificial intelligence, could very well have an overall competitive advantage.”53 AI functions as a force multiplier by improving vision and targeting, mitigating manpower issues, hardening cyber defenses, and accelerating decisionmaking. Its advantages were plain to see in the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency’s August 2020 AlphaDogfight Trials, when an AI algorithm swept a human F-16 pilot 5 to 0. In the past decade, DOD stood up new organizations such as the Defense Innovation Unit and Strategic Capabilities Office and announced its Third Offset Strategy, an initiative to preserve the U.S. military’s technological edge against rising peer competitors.54 Similarly, reflecting an acute appreciation of AI’s disruptive potential, Beijing launched a strategy to achieve AI dominance by 2030 and introduced the concept of “intelligentization” of warfare to operationalize AI and its enabling technologies, including cloud computing and unmanned systems.55

China is ahead in some sectors of quantum technology, a game-changing asset that could guarantee secure communications, expose stealth aircraft, complicate submarine navigation, and disrupt battlefield communications.56 In 2016, China introduced a quantum technology strategy to achieve major breakthroughs by 2030 and launched the world’s first quantum satellite. Also that year, Chinese company China Electronics Technology Group Corporation reportedly developed the first quantum radar that could detect stealth aircraft and resist jamming and spoofing, leaving Lockheed Martin, which had been experimenting with this technology for nearly a decade, in its rearview mirror.57 And in June 2016, the Shanghai Institute of Microsystem and Information Technology announced that it had built what could be the world’s longest-range submarine detector using a cryogenic liquid nitrogen–cooled superconducting quantum interference device magnetometer.58 As National Security Council Senior Director for Technology and National Security Tarun Chhabra has written, although the United States has an overall edge in quantum computing, Beijing is on pace to overtake this advantage if the United States idles.59

China also leads the United States in developing hypersonic weapons, which exceed Mach 5 and maneuver to their target.60 According to the Defense Intelligence Agency, hypersonic weapons will “revolutionize warfare by providing the ability to strike targets more quickly, at greater distances, and with greater firepower.”61 While Beijing has successfully tested its DF-17 hypersonic missile on multiple occasions as well as a nuclear-capable Fractional Orbital Bombardment System equipped with a hypersonic glide vehicle, it will be years until the United States has a similar platform.62

Meanwhile, Xi Jinping has extended his “China Dream” into a “space dream.” Beijing operates over 120 intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance and remote sensing satellites—second only to the United States—while expanding its BeiDou precision, navigation, and timing system as an alternative to GPS.63 In 2019, the BeiDou constellation surpassed GPS in size and visibility.64 In April 2021, China launched the core module of its first long-term space station, achieving in 20 years what took the United States 40.65 As the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission concluded, “China’s single-minded focus and national-level commitment to establishing itself as a global space leader . . . threatens to undermine many of the advantages the United States has worked so long to establish.”66

Beijing’s acquisition of frontier technologies has been guided by key organizing concepts, including what it calls “civil-military fusion” and “leapfrog development.”67 As part of China’s extensive military reforms inaugurated in 2016, civil-military fusion facilitates technological transfers between the defense and civilian sectors, builds cohesion among researchers in support of military objectives, and drives innovation.68 Simultaneously, the PLA has sought to achieve advantages in what it calls “strategic frontline” technologies that the United States has not mastered or may not be capable of mastering.69

China may also be ahead in aligning frontier technologies with warfighting concepts that exploit them. Beijing’s warfighting concept of “system destruction warfare” envisions future warfare as a contest of operational systems. PLA planners prioritize achieving information superiority by crippling an opponent’s battle networks at the outset of conflict using a suite of capabilities, including antisatellite and electromagnetic pulse weapons. In 2015, China took a crucial step toward preparing for system destruction warfare by establishing its Strategic Support Force, which centrally coordinates the PLA’s space, cyber, and electronic warfare capabilities. China’s doctrinal innovations may give it an edge in a potential conflict with the United States. As former Deputy Secretary Work cautioned, “The side that finds the better ‘fit’ between technology and operational concepts likely will come out on top.”70

While the PLA has focused on the future fight, the United States military has optimized for low-intensity operations, doubled down on legacy platforms, and left innovating startups struggling to survive the Pentagon’s acquisitions process.71 For 20 years, the Pentagon prioritized counterinsurgency and counterterrorism—in Admiral Winnefeld’s words, “sticking its head in the sand.”72 Meanwhile, as General Milley put it, China “went to school” on the U.S. military’s strategy and capabilities: the PLA “watched us very closely in the First Gulf War, Second Gulf War, watched our capabilities and in many, many ways they have mimicked those and they have adopted many of the doctrines and the organizations.”73 Likewise, the Chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee Jack Reed has noted, “For the past several decades, China has studied the [U.S.] way of war and focused its efforts on offsetting our advantages. This strategy has been successful, largely because China began without any significant legacy systems.”74 As a result, as defense analyst Andrew Krepinevich warned, the United States today is at risk of “having the wrong kind of military, conducting the wrong kinds of operations, with the wrong equipment.”75

Rendering of Tiangong Space Station between October 2021 and March 2022, with Tianhe core module in the middle, two Tianzhou cargo spacecrafts on left and right, and Shenzhou-13/14 crewed spacecraft at nadir.

The Curious Question of Defense Spending

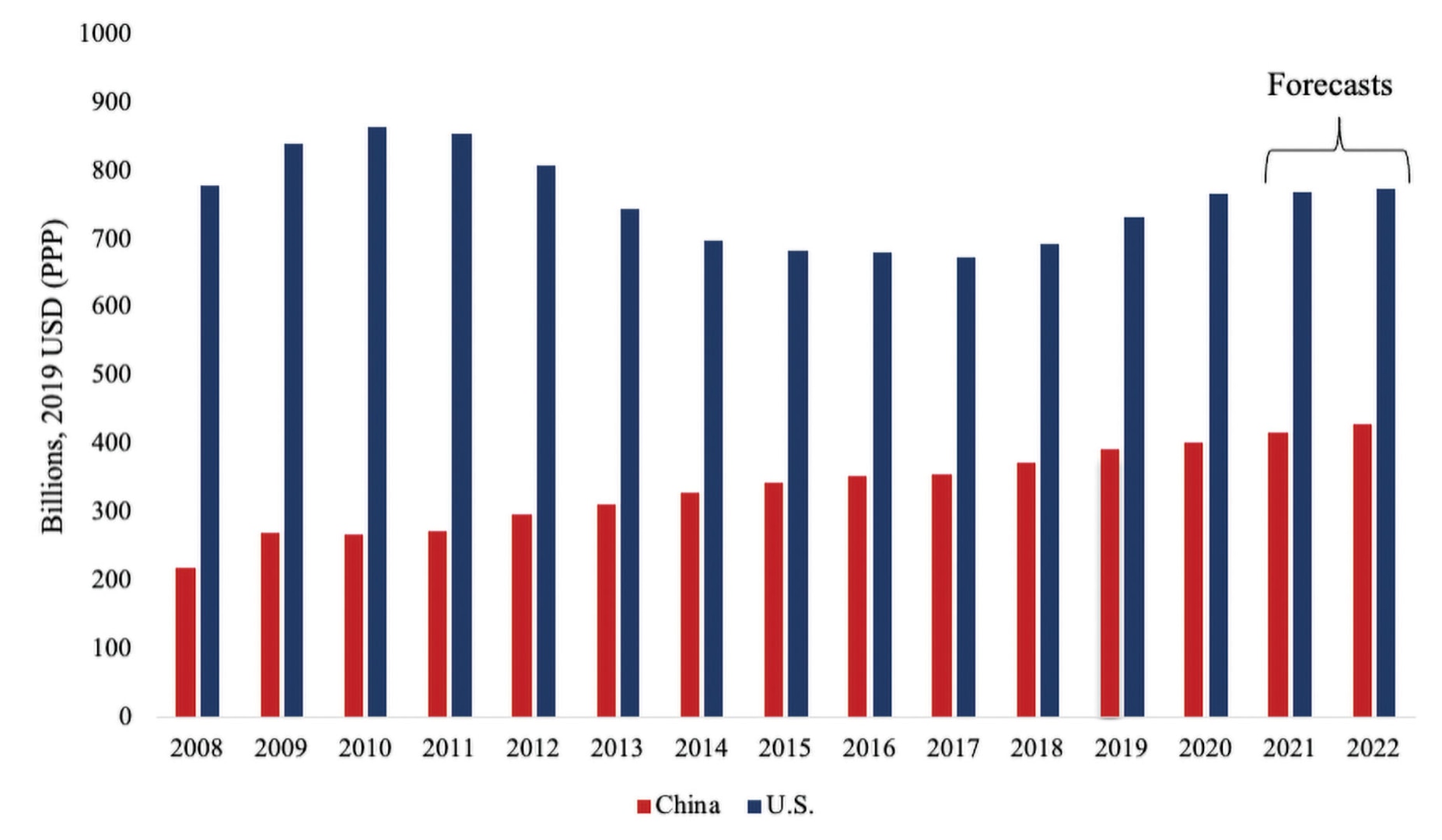

Skeptics who find it hard to believe claims about a dramatic shift in the military balance under way often ask, “But doesn’t U.S. defense spending dwarf that of China?” The answer is yes, but the reality is more complicated. Measured by the traditional yardstick, market exchange rate, in 1996, China’s reported defense budget was 1/30 the size of America’s. By 2020, it was one-quarter.76 When spending that appears in other budgets—for example, on military research and development—is included, its actual defense budget is one-third America’s.77 And if measured by the best yardstick of economic and military potential (purchasing power parity [PPP]), Beijing’s defense budget is over two times its stated budget—which brings it to over half of America’s and on a path to parity.

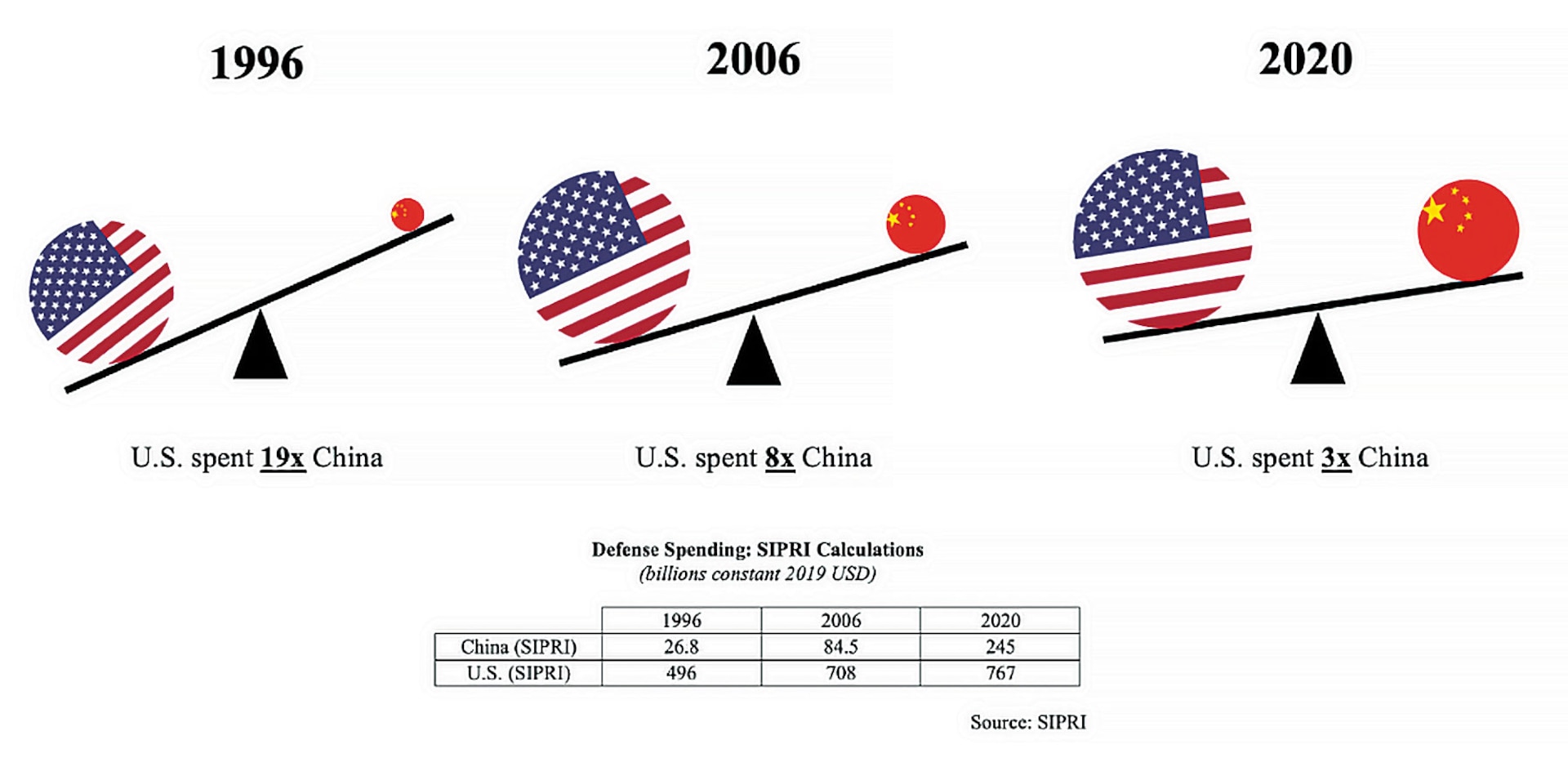

In 2020, the U.S. defense budget was $738 billion, while China’s reported budget was $178 billion at the prevailing market exchange rate.78 But when items that China excludes from its official reports that appear in the U.S. defense budget, including research and development (on which the United States spends over $100 billion), veterans’ retirement payments, and construction expenses, are included, as the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute found, since 1996 the gap in spending narrowed from 19:1 to 3:1.79

Moreover, in comparing defense budgets, it is essential to consider not only how much each pays for items but also what each gets at the prices paid. Both the CIA and the IMF have concluded that the best single metric for comparing national expenditures is PPP. As the Economist has illustrated vividly in its “Big Mac index,” for the $5.81 a consumer pays for one Big Mac in the United States, one gets one and a half Big Macs in Beijing. Similarly, when the PLA buys bases or ships or DF-21 missiles, it pays in renminbi and at prices substantially below the cost of equivalent products in the United States.80

Figure 2.

The most vexing issue in comparing defense spending is personnel costs. Because of the complexity, differences are often relegated to a footnote. But as General Milley noted pointedly in his testimony to Congress in 2018, when he was Chief of Staff of the Army, “What is not often [accounted for] is the cost of labor, and anyone who takes Econ 101 knows cost of labor is the biggest factor of production . . . we’re the best paid military in the world by a long shot. . . . Chinese soldiers [cost] a tiny fraction.”81 Milley is certainly correct. The average PLA active-duty soldier costs China one-quarter what the United States pays. DOD currently spends on average over $100,000 per Active-duty Servicemember annually, including salary, benefits, and contributions to retirement programs.82 In contrast, the PLA’s budget for each of its 2.035 million active-duty personnel is on average $28,000.83

Three further differences are worthy of note. First, the U.S. defense budget pays for bases and forces to meet global commitments in Europe, the Middle East, South America, and Asia. The United States currently maintains 750 overseas bases around the world.84 Thus, while the U.S. Indo-Pacific Command’s area of responsibility includes half the world’s population and two of its three largest economies, its commander must compete for funding with other commanders responsible for the many other U.S. commitments.85 China’s defense budget, by contrast, is focused on Northeast Asia.

Second, much of the U.S. acquisition budget is consumed by exquisite and expensive legacy systems dear to each of the military Services but not well designed for a potential conflict with China. The escalation in costs of these systems was captured by one of the wisest leaders of America’s defense world, Norman Augustine, in the early 1980s, when he coined what has become known as Augustine’s Law. According to this law, the cost of American weapons doubles every 5 years. To be even more provocative, he quipped that on the trajectory at the time, by 2054 “the entire defense budget will purchase just one aircraft. This aircraft will have to be shared by the Air Force and Navy three and a half days each per week except for leap year, when it will be made available to the Marines for the extra day.”86 In 2010, the Economist reviewed what had happened in previous decades, compared it to the trajectory forecast by Augustine’s Law, and concluded that “we are right on target.”87

Figure 3.

As a result, as Christian Brose has argued, in the competition with China, the United States is “playing a losing game.” While the United States has built “small numbers of large, expensive, exquisite, heavily manned, and hard-to-replace platforms,” China has developed “large numbers of multi-million-dollar weapons to find and attack America’s small numbers of exponentially more expensive military platforms.”88 As National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan put it, “for every $10,000 we spend on an aircraft carrier, [China spends] $1 on a missile that can destroy that aircraft carrier.”89

Third, for the past two decades, much of U.S. spending has gone to wars in the Middle East and been handicapped by paralysis in Congress. As General Dunford told Congress in 2019, “seventeen years of continuous combat and fiscal instability have affected our readiness and eroded our competitive advantage.”90

The cost of the war on terror now exceeds $6.4 trillion, including $2 trillion in Afghanistan.91 At the height of the U.S. troop presence in Afghanistan and Iraq in 2010, defense spending reached almost $820 billion and 4.7 percent of gross domestic product (GDP).92 After the 2011 Budget Control Act introduced cuts, partisan jockeying led to delayed budgets and a government shutdown in 2013, followed by declining defense outlays for 2 years. Although spending has risen slightly since 2016, by 2020, defense expenditures constituted the lowest percentage of GDP and Federal discretionary spending since 1962.93 These figures are markedly below the bottom line of 3 percent annual growth above inflation that General Dunford told Congress is the floor necessary to preserve America’s “competitive advantage.”94

Figure 4.

In sum, emerging from what former Secretary of Defense Mattis has called a period of “strategic atrophy,” serious American strategists have increasingly recognized the demise of U.S. military dominance and are now struggling to understand what that means for our national security and defense.95 All agree that to restore strategic solvency in a deteriorating security landscape, the United States must find more imaginative ways to adapt.

Where Do We Go from Here?

Our objective in this article is to report the facts about where the United States and China currently stand in key races. We hope this summary of what has happened can inform the Biden administration’s strategic reviews—not anticipate their conclusions. Choices the administration and Congress will make in 2022 and beyond can significantly impact the current trajectories. But the decisions likely to have the greatest positive impact are the hardest to make and execute. For example, as Admiral Winnefeld, former CIA Acting Director Michael Morell, and Graham Allison explained in their Foreign Affairs article “Why American Strategy Fails,” the legacy platforms we have, to which core groups within the military Services are committed and which are supported by congressional subcommittees and industry lobbyists, are mostly not what the Nation needs if China is the defining military challenge for the decades ahead.96 As Admiral Winnefeld put it, the U.S. military is on a “non-virtuous flywheel . . . maintained by powerful incentives for Congress (money in Members’ districts), identity metrics for the services (ship numbers), and a lack of imagination on the part of the combatant commands.” As a result, the military is too often “merely trying harder to do the same things and demanding more resources to chase the same increasingly moribund concept (decisive mano-a-mano power projection).”97

No comments:

Post a Comment