P. K. Balachandran

China to celebrate centenary of Tagore’s 1924 visit in collaboration with Santiniketan

India and China have been antagonistic since the late 1950s. The Chinese invasion of India in 1962, the border clashes of 2020, retaliatory sanctions against Chinese mobile products, restrictions on the learning of the Chinese language, have made rapprochement seem impossible.

But there is light at the end of the tunnel.

In his interview to Newsweek, which is the first to be given to a US magazine in the recent past, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi said that for India, the relationship with China is important and significant.

“It is my belief that we need to urgently address the prolonged situation on our borders so that the abnormality in our bilateral interactions can be put behind us. Stable and peaceful relations between India and China are important for not just our two countries but the entire region and world,” he said.

The Chinese Foreign ministry spokesperson Mao said the boundary question “does not represent the entirety of the India-China relations. It should be placed appropriately in the bilateral relations and managed properly. The two sides are in close communication through diplomatic and military channels,” she said.

“We hope India will work in the same direction with China, handle the bilateral relations from the strategic heights and long-term perspective, enhance mutual trust, stick to dialogue and cooperation, handle differences properly and put the bilateral relations forward on sound and stable track, she said.

Tagore Bridges the Divide

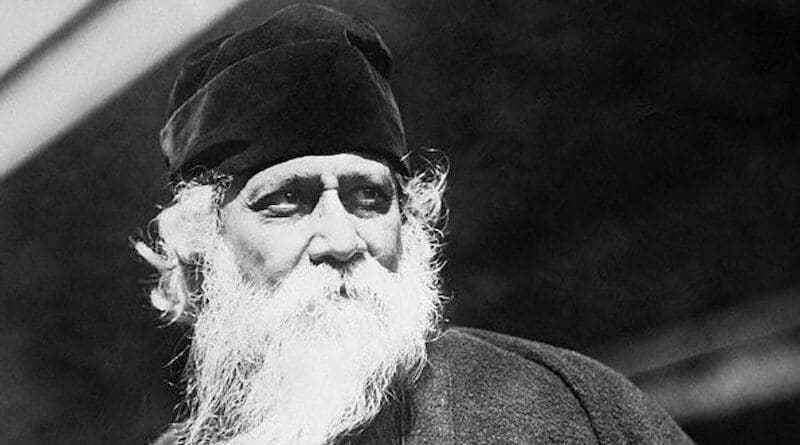

Meanwhile, a shared interest in India’s first Nobel Laureate Rabindranath Tagore is being used by both sides to re-establish cultural and educational ties.

China is to celebrate centenary of Tagore’s 1924 visit in collaboration with Santiniketan and is set to renew its ties with the Cheena Bhavana in Santiniketan to further the study of Chinese language and culture. These ties had snapped in 2020.

Earlier this month, the Viswa-Bharati University in Santiniketan, founded by Rabindranath Tagore, and the Chinese Embassy in India, discussed the revival of cultural and educational exchanges between Viswa-Bharati and Chinese Universities at a seminar in Santiniketan.

Between 2010 and March 2020, teams from 20 Chinese universities, including Peking University, Yunnan University and Yunnan Minzu University, had participated in Santiniketan’s exchange programmes regularly. But these stopped in 2020 partly because of the pandemic and partly because the border clashes between Chinese and Indian troops.

But there are plans to revive the collaboration in October this year.

Prior to that on April 13, Shenzhen University is organizing a symposium to commemorate the centenary of Tagore’s visit. In May, China will organize a conference in Beijing to mark the 100thanniversary.

Tagore had visited China twice, in 1924 and 1928. On his first visit, he had stayed for 49 days. The Chinese embassy has requested Viswa-Bharati University to send a delegation to participate in the event.

Ma Jia, the Chargé d’Affaires of the Chinese embassy, who took part in the discussions at Santiniketan, said that Tagore’s visits to China constituted a “milestone that still plays an important role in promoting exchanges and mutual learning between the two major civilizations of China and India. China and India should inherit and carry forward Tagore’s great spirit, deepen people-to-people and cultural exchanges between China and India, and add more positive factors to China-India relations.”

Tagore’s Visits

In a lecture at the Singapore Consortium for China-India Dialogue in 2011, the then Indian Foreign Secretary, Nirupama Rao, pointed out that during his visits to China in 1924 and 1928, Tagore had met top Chinese scholars such as the Minister of Justice and intellectual, Liang Quicho (1873-1929) and Chinese poet and writer Xu Zhimo (1897-1931).

Interestingly, one of the earliest admirers of Tagore was Chen Du Xiu, one of the founding fathers of the Communist Party of China. Chen had translated Tagore’s prize-winning anthology, ‘Gitanjali’ as early as 1915. The renowned Chinese scholar, Liang Qichao, had given Tagore the Chinese name, ‘Zhu Zhendan’ which translated as “thunder of the oriental dawn”.

The late Ji Xianlin, the Chinese Indologist who was awarded the Padma Bhushan by India years later, said that Tagore was an icon of Sino-Indian friendship both in India and China.

“China and India” Ji said: “have stood simultaneously on the Asian continent. Their neighbourliness is created by Heaven and constructed by Earth.”

According to Rao, Tagore truly believed in the mutually beneficial interactive relationship between the two great civilizations of China and India. He passionately advocated the reopening of the path between the two countries that had become obscured through the centuries.

In one of his lectures in China in 1924, Tagore said: “I hope that some dreamer will spring from among you and preach a message of love and therewith overcoming all differences bridge the chasm of passions which has been widening for ages.”

In Tagore’s view, there was no fundamental contradiction between the two countries whose civilizations stressed the concept of harmonious development in the spirit of ‘vasudhaiva kutumbakam’ (the world is one family) and ‘Shijie Datong’ (world in grand harmony), Rao said.

Left Wing Criticism

But Chinese left wing intellectuals were highly critical of Tagore’s soft approach to imperialism. Shyam Saran, another of India’s Foreign Secretaries, in his book ” How China sees India” (Juggernaut Books 2022) said that Chinese Left wingers dubbed Tagore a weak man.

One of them Shen Yanbing wrote about Tagore’s visit thus: “We are determined not to welcome the Tagore who loudly sings the praises of Eastern civilization nor do we welcome the Tagore who creates a paradise of poetry and love and leads our youth into it so that they might find comfort and intoxication in meditating.”

Rao’s Rebuttal

Correcting this impression, Rao said: “Tagore neither sought to perpetuate the political or social status quo of China nor impose the self-negating values of India, as his critics in China at that time alleged. Instead, Tagore’s was an effort to shift the attention of both India and China from the West, whose power and prestige at that point were at their zenith but also produced war and turmoil, to each other as well as to their past glory and their harmonious contacts.”

“Tagore wanted India and China as fountainheads of ancient civilizations to take pride in their rich heritage and draw from their past to build a future of friendly contacts. While aware of somewhat unidirectional past contacts between them in the religious realm, Tagore did not attempt to persuade China to accept another wave of cultural influence from India. He merely asked China to join him in his experiment of building institutions based on the “ideal of the spiritual unity of all races”.

Rao pointed out Tagore’s great sensitivity to the plight of the Chinese people.

“When he was all but 20 in 1881, he authored an essay vehemently denouncing the opium trade which had been imposed on China since that opium was mostly being grown in British India. He called this essay ‘Chine Maraner Byabasay’ or the “Commerce of Killing people in China” Rao said.

He expressed similar feelings of sympathy after the Japanese invasion of China writing to his friend, a Japanese poet, Yone Noguchi. “The reports of Chinese suffering batter against my heart,” Tagore wrote.

In Rao’s view, Tagore reflected the spirit of an Asia which had traditionally lived in peace, pursuing the traffic of ideas. Peaceful absorption of different religions without proselytization was the norm. Trade and commerce across oceans were not polarized. The Oceans were zones of peace and a common economic space.

Cheena Bhavana

In 1937 Tagore set up an institution called Cheena Bhavana in Santiniketan to promote the study of the Chinese language and culture with the participation of two Chinese scholars, Tan Yunshan and Wi Xioling and artists like Xu Beihong. Tan Yunshan became the first Director of Cheena Bhavana. Tan Yushan’s son, Tan Chung, was to be Professor of Chinese at Delhi University for many years.

The Cheena Bhavana went on to offer graduate and post graduate courses. It has a library of over 40,000 books now.

No comments:

Post a Comment