Kat Duffy and Kyle Fendorf

The gathering, selling, buying, aggregation, and redeployment of data—including highly personal data—has fueled the growth of the U.S. economy for decades. With the age of artificial intelligence (AI) firmly at hand, this commodification of data has also generated new and untenable national security threats that are exacerbated by the continued absence of a comprehensive federal privacy law. Authoritarian states are already taking advantage of the U.S. commercial data market. China maintains a large system to gather up data on social media users, including those on X and Facebook in the United States and abroad. It uses this data to monitor public opinion in the United States, track dissidents abroad, and anticipate potential threats to the regime. The United States’ current capacity to mitigate the risks of its commercial data market is limited. Indeed, the Joe Biden administration’s recent actions addressing Chinese-made electric vehicles (EVs) demonstrate how limited federal authorities are in protecting against national security risks centered on data security, as opposed to those based in economic competitiveness or cybersecurity.

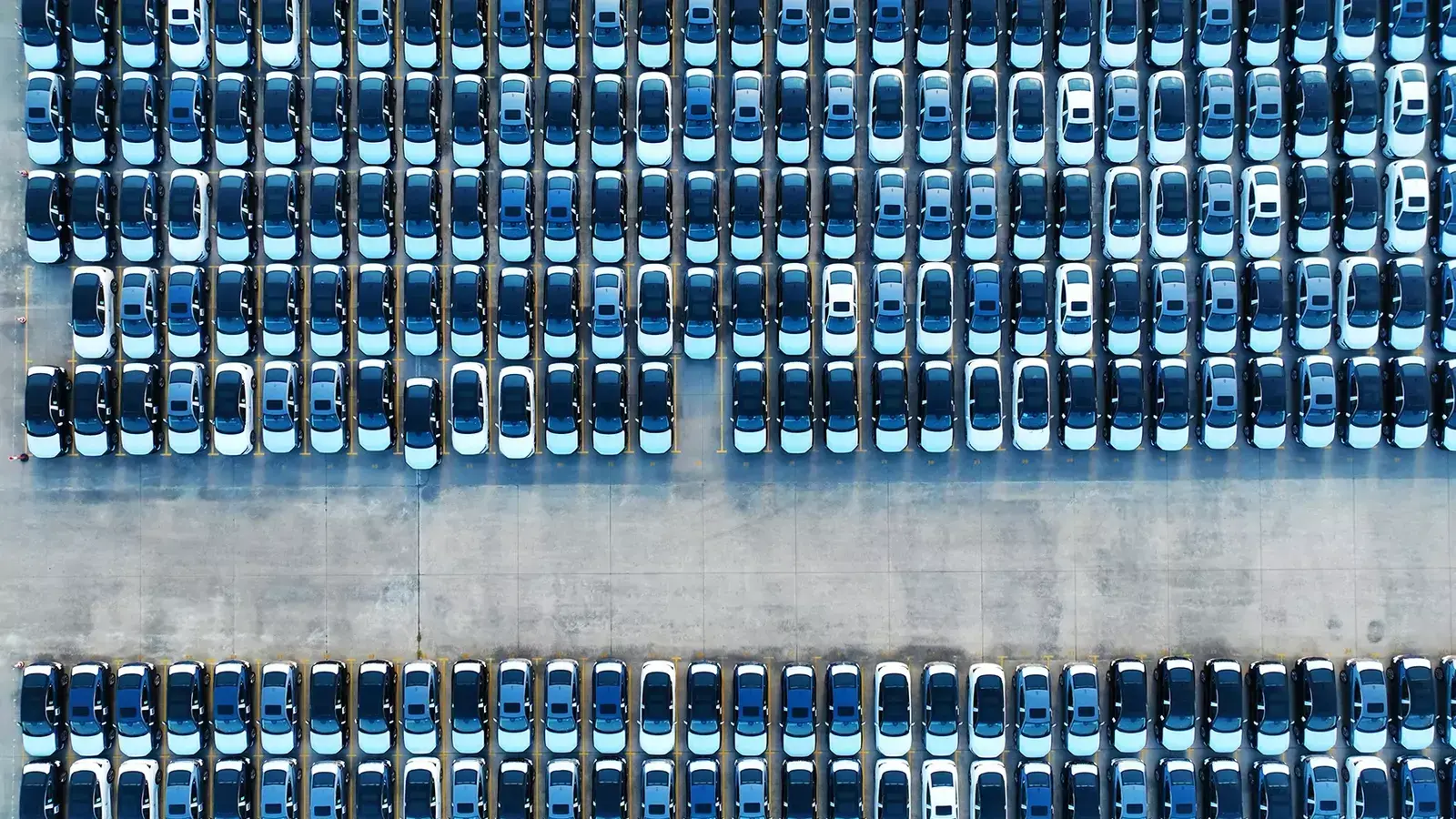

Both the Donald Trump and the Biden administrations have enacted policies to address economic competitiveness concerns around EVs, such as the Trump administration’s use of Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962 to impose 25 percent tariffs on Chinese EVs in 2019. Even such high tariffs could provide inadequate protection against market entry: in 2022, Chinese companies accounted for 35 percent of all EV exports globally, and Chinese-made EVs (which are heavily subsidized) are expected to comprise a quarter of the electric vehicles sold in Europe this year. This rapid growth has understandably concerned U.S. industry leaders and policymakers, not only because of its implications for the U.S. auto industry and economic competition, but also because EVs pose unique cybersecurity threats.

For example, computers in EVs often use vehicle-to-grid charging, which could be used as a jumping-off point to infiltrate critical infrastructure—a threat that could only grow as the United States invests in building a broader EV-charging grid. In addition, bipartisan policies have long supported limiting Chinese-made products’ access to U.S. critical infrastructure systems: in 2019, the Trump administration launched a $6 billion “rip-and-replace” program to completely remove equipment made by Chinese telecommunications firms Huawei and ZTE from U.S. networks.

When it comes to risks centered on data security, fewer immediate protections are at hand. This could be one reason the Biden administration unleashed a flurry of expansive executive actions in February leveled, in part, at Chinese EVs. The Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) issued an Advanced Notice of Proposed Rulemaking that will give BIS sixty days to investigate and take public comments on cybersecurity and data security concerns around “connected vehicles” (i.e., any modern vehicle) produced by six “countries of concern.” (China is the only country among the six that exports vehicles.) Launching the BIS investigation required the Biden administration to stretch its existing authorities: this marked the first time that Executive Order 13873 has been used to investigate an entire class of products, rather than those produced by a single company. On the same day, the Biden administration announced Executive Order 14117, aimed at limiting the sale of certain kinds of bulk data to companies and organizations in the same six countries of concern—but this data was limited to that which can clearly be defined as affecting national security, such as bulk sales of genomic data or the locations of military personnel.

The executive branch is right to be concerned: modern vehicles collect and transmit enormous amounts of data with little to no oversight. U.S. automakers already admit they collect audio recordings of occupants, driving habits, data from third-party devices connected to vehicles (including cell phones), precise geolocation data, and even drivers’ facial geometry. This information—some of it gathered by a vehicle company, some gathered by third company vendors—can then be sold to commercial data brokers, aggregated, and resold. For example, General Motors shared data on dates, distances, and times for individual drivers’ trips, as well as speed, braking, and acceleration patterns, with data broker LexisNexis for years before announcing it would stop on March 22 after the New York Times exposed the practice. EVs turbocharge those data risks, as batteries leave more room for computers and wiring than gasoline engines and offer more power for networks. Autonomous vehicles could expand risk even more as they gain popularity, given the extraordinary amounts of data they need to collect to operate safely.

As Secretary of Commerce Gina Raimondo noted in January, “it doesn’t take a lot of imagination to think of how foreign governments with access to connected vehicles could pose a serious risk to both our national security and the personal privacy of U.S. citizens.” This statement encapsulates a fundamental challenge. Entry into the U.S. vehicle market can be controlled with economic tradecraft. Entry into U.S. critical infrastructure can be controlled (to some degree) through cybersecurity controls over physical access. But when it comes to data access, crucial vulnerabilities remain even if Chinese EVs never cross U.S. borders. China is already engaged in an enormous effort to capture Americans’ data, and it does not need vehicles on the ground to do so: it can simply purchase the data it wants directly or through third-party data brokers.

Many U.S. data security risks would be better addressed by a national data privacy regulation, as is the case in Europe, where the EU General Privacy Data Regulation governs the collection, use, and resale of data generated by vehicles. As the AI age emerges, the United States’ lack of a clear, comprehensive, federal data-privacy standard will create even greater, and still unknown, risks. For a hungry AI developer, the ability to buy up Americans’ personal data is as enticing as a cheap, all-you-can-eat buffet is to a teenage athlete. And no one is clear on what will result: the insights that new AI models could generate remain unknown, but the value of gathering data—particularly high-quality, structured, standardized data that can be replicated—will be significant. The data market will continue to grow, and as it does, so too will the range of national security risks that market creates.

The Biden administration’s efforts to work creatively within its existing authorities to minimize such risks are simultaneously laudable and incapable of meeting the challenge at hand. Beyond protecting Americans’ basic rights to privacy, a federal data-privacy standard would put far less pressure on the executive branch to develop bespoke solutions to a blanket problem. Unfortunately, until Congress finally acts to exert its own authority to protect Americans’ data, every current and future president will be operating according to Theodore Roosevelt’s long-held maxim: “Do what you can, with what you’ve got, where you are.”

No comments:

Post a Comment