Dr. Erica Lonergan & RADM (Ret.) Mark Montgomery

Executive Summary

In the U.S. military, an officer who had never fired a rifle would never command an infantry unit. Yet officers with no experience behind a keyboard are commanding cyber warfare units. This mismatch stems from the U.S. military’s failure to recruit, train, promote, and retain talented cyber warriors. The Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marines each run their own recruitment, training, and promotion systems instead of having a single pipeline for talent. The result is a shortage of qualified personnel at U.S. Cyber Command (CYBERCOM), which has responsibility for both the offensive and defensive aspects of military cyber operations.

For the last decade, Congress, on a bipartisan basis, has made clear its sharp concern about cyber personnel issues. In 2022, it required the secretary of defense to deliver a report that addresses “how to correct chronic shortages of proficient personnel in key work roles” at CYBERCOM. The report is due on June 1.1

Often, however, military leaders have addressed personnel shortages by massaging statistics rather than fixing the underlying problem. In 2018, CYBERCOM appeared to reach a major milestone when it certified that all 133 of its Cyber Mission Force (CMF) teams had enough properly trained and equipped personnel to execute their missions. Yet multiple officers revealed these certifications to be hollow; CYBERCOM merely shifted a limited number of effective personnel from team to team to make them appear complete at the time of certification.

To deepen the understanding of the cyber personnel system and its flaws, this study draws on more than 75 interviews with U.S. military officers, both active-duty and retired, with significant leadership and command experience in the cyber domain.2 The study identifies these officers by rank and service but withholds their names for reasons of privacy.

This research paints an alarming picture. The inefficient division of labor between the Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps prevents the generation of a cyber force ready to carry out its mission. Recruitment suffers because cyber operations are not a top priority for any of the services, and incentives for new recruits vary wildly. The services do not coordinate to ensure that trainees acquire a consistent set of skills or that their skills correspond to the roles they will ultimately fulfill at CYBERCOM. Promotion systems often hold back skilled cyber personnel because the systems were designed to evaluate servicemembers who operate on land, at sea, or in the air, not in cyberspace. Retention rates for qualified personnel are low because of inconsistent policies, institutional cultures that do not value cyber expertise, and insufficient opportunities for advanced training.

Resolving these issues requires the creation of a new independent armed service — a U.S. Cyber Force — alongside the Army, Navy, Air Force, Marine Corps, and Space Force. There is ample precedent for this approach; battlefield evolutions led to the establishment of the Air Force in 1947 and the Space Force in 2019. An independent cyber service would naturally prioritize the creation of a uniform approach to recruitment, training, promotion, and retention of qualified personnel whose skills correspond to CYBERCOM’s needs. In addition to a single, dedicated cyber training and development schoolhouse, an independent service could establish a cyber war college for advanced research and training, akin to the Army War College and its peers. Without the responsibility for procuring planes, tanks, or ships, a Cyber Force could also prioritize the rapid acquisition of new cyber warfare systems.

This Cyber Force need not be large. An examination of existing cyber billets suggests it would initially comprise about 10,000 personnel but might grow over time. As the Space Force has shown, a smaller service can be more selective and agile in recruiting skilled personnel.

Some military experts have proposed alternative approaches to addressing the U.S. military’s cyber personnel shortage, but each has major shortcomings. For example, some argue that CYBERCOM should become more like the U.S. Special Operations Command, to which each service provides elite personnel uniquely trained for the land, sea, and air domains. But that model makes little sense for cyberspace since there are no cyber functions specific to the other warfighting domains. Others argue CYBERCOM should assume responsibility for manning, training, and equipping cyber forces in addition to employing them on the virtual battlefield. But this approach would break with 40 years of precedent and would overwhelm CYBERCOM’s leadership, which is already dual hatted with the National Security Agency, an arrangement that serves U.S. national security well.

America’s cyber force generation system is clearly broken. Fixing it demands nothing less than the establishment of an independent cyber service.

Illustrated prospective seal for U.S. Cyber Force (Design by Daniel Ackerman/FDD)

History and Current Organization of the U.S. Military in Cyberspace

For nearly 40 years, the U.S. military has separated the responsibility for force generation — the imperative to “man, train, and equip” personnel for their specific domains — from the responsibility of force employment — the use of troops in combat. The independent services — the Army, Navy, Air Force, Marine Corps, and Space Force — generate forces, while the unified combatant commands employ forces and can request manpower from each of the services.

For every domain but cyberspace, the United States has designated a single service as the one ultimately responsible for force generation for its respective domain. For example, while the Army, Navy, and Marine Corps operate significant aircraft fleets, it is primarily the Air Force’s responsibility to man, train, and equip U.S. troops for air combat.

Since the establishment of CYBERCOM in 2010 and its subsequent elevation to a unified combatant command in 2018, the military has had a designated organization for force employment in and through cyberspace. But the United States still has no single entity responsible for cyber force generation.

The Creation of CYBERCOM

The pivotal role of advanced technology in the 1991 Gulf War led the Department of Defense (DoD) to recognize the importance of what were then known as “computer network operations.”3 The U.S. military began developing cyber doctrine in earnest in 2003 after the discovery of a multi-year Russian cyber espionage operation revealed the “first large-scale cyberespionage attack by a well-funded and well-organized state actor.”4 The next year, the Joint Chiefs of Staff defined cyberspace as a warfighting domain,5 and DoD released its first National Military Strategy for Cyberspace Operations in 2006.6 (A more detailed account can be found in Appendix C.)

After discovering additional foreign cyber espionage campaigns targeting the department, DoD in 2010 combined existing cyber elements to establish CYBERCOM under U.S. Strategic Command. CYBERCOM is led by a commander dual hatted as director of the National Security Agency (NSA), the intelligence community component responsible for signals intelligence and cybersecurity services. CYBERCOM became responsible for defending DoD information systems, supporting joint force commanders in cyberspace, and advancing national interests in and through cyberspace.

The services also developed their own components responsible for information and cyber operations in support of operations in their respective warfighting domains. These components include what are now the 16th Air Force, Army Cyber Command, Fleet Cyber Command, and Marine Corps Forces Cyberspace Command.

In 2018, the president elevated CYBERCOM to a unified combatant command. This move retained the dual-hatted structure and gave CYBERCOM a direct line of communication to the secretary of defense plus greater authority to request budgetary resources.7

Despite standing up CYBERCOM, the military has not established a cyber-specific training academy. In other areas, institutions such as the U.S. Army War College, U.S. Naval War College, Air War College, U.S. Marine Corps University, and National Defense University provide specialized training for senior enlisted personnel and officers, preparing them for leadership positions and assignments in the joint force. This is known as force development.8

The 2019 National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence argued for the creation of a Digital Service Academy to address talent deficits in the defense and intelligence communities.9 DoD’s failure to implement this recommendation after three years and multiple congressional initiatives10 suggests such an academy will not succeed absent an independent service that can deliver the expertise and resources to equip a cyber-specific service academy.

Current Organization of the U.S. Military in Cyberspace

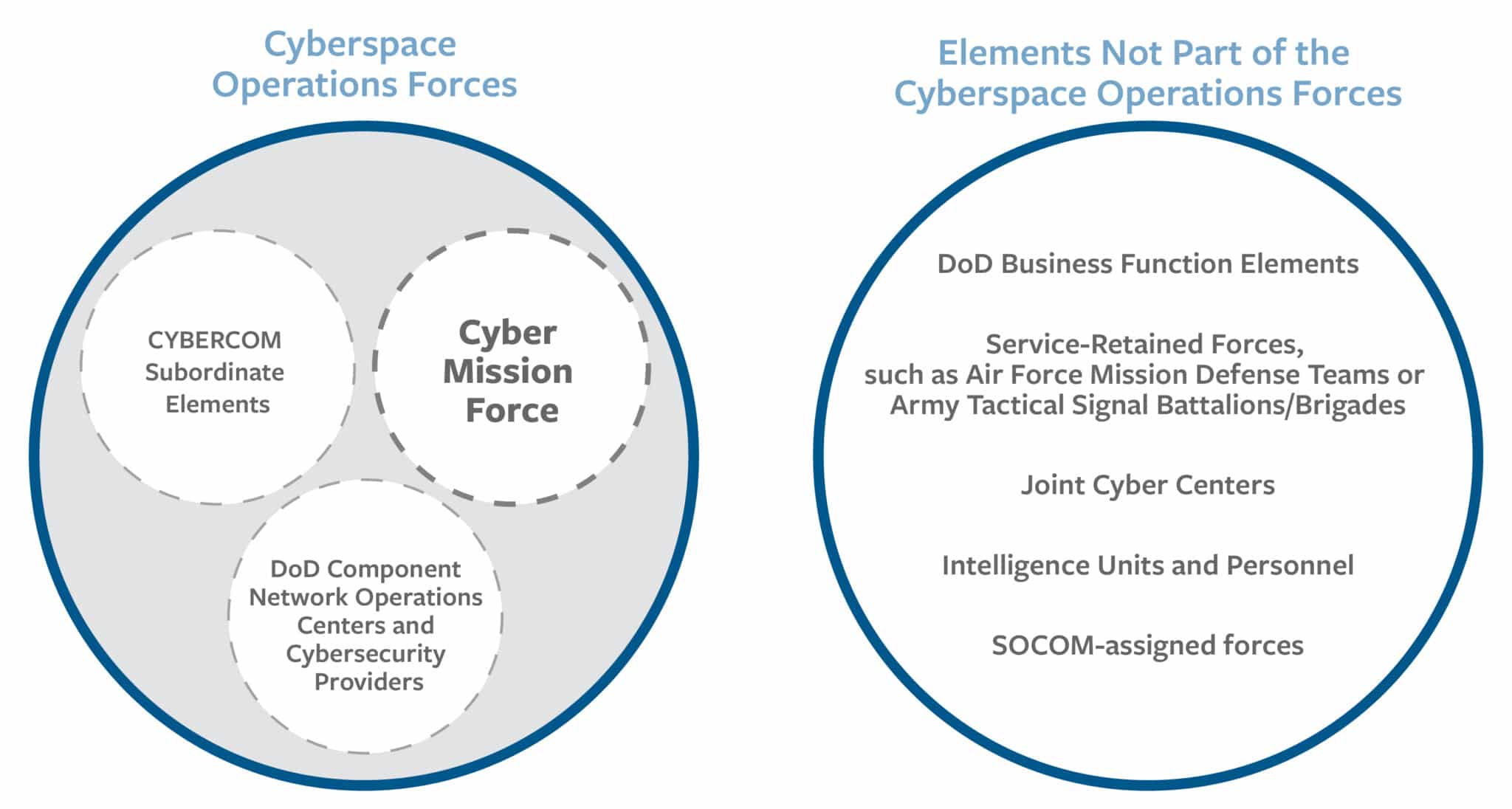

The U.S. military’s Cyberspace Operations Forces (COF)11 encompass elements that conduct reconnaissance, operational preparation of the environment, and network-enabled operations, along with subordinate logistics and administrative elements.12 In addition, the COF includes DoD network operations centers and cybersecurity service providers that conduct traditional network defense and information technology (IT) support functions. This latter group makes up the bulk of COF personnel.13 Separately, some U.S. military cyber personnel, serving outside the COF, conduct traditional business functions, protect service-specific systems, and support other functional or geographic commands (see Figure 1 below).

Figure 1: Cyberspace Operations Forces

Within the COF, the Cyber Mission Force directs, coordinates, and executes cyber operations. It comprises less than 3 percent of the COF, or approximately 6,200 military and civilian personnel.14 The CMF currently includes 133 teams. But in 2022, DoD announced the CMF would expand to 147 teams, including:15

- Thirteen Cyber National Mission Force (CNMF) teams responsible for “defend[ing] the nation by seeing adversary activity, blocking attacks, and maneuvering in cyberspace to defeat them.” These operations are largely conducted as independent campaigns, not in support of combatant command missions.

- Twenty-seven Cyber Combat Mission Teams, which “conduct military cyber operations in support of combatant commands.”

- Sixty-eight Cyber Protection Teams responsible for “defend[ing] the DOD information networks, protect[ing] priority missions, and prepar[ing] cyber forces for combat.”

- Twenty-five Cyber Support Teams, which provide analytic and planning support to CNMF and the Cyber Combat Mission Teams.16

- Fourteen new teams responsible for supporting combatant commanders in space operations and countering cyber influence.

In 2018, CYBERCOM attested that the original 133 CMF teams achieved full operational capacity (FOC). In other words, each team ostensibly had the ability to fully employ its cyber weapons with adequately trained, equipped, and supported servicemembers.17 Of those 133 CMF teams, 41 came from the Army, 40 from the Navy, 39 from the Air Force, and 13 from the Marine Corps.18

In 2022, the CNMF became a sub-unified combatant command, endowing it with additional authorities and responsibilities. Its commander explained that this status will enable CNMF to build “a force that can move faster than our adversaries, because we have the right set of equipment, the right authorities, and the right procedures that move with agility and speed.”19

The 14 additional CMF teams are supposed to be stood up between fiscal years 2022 and 2026. Five of the new teams are slated to come from the Army, with the Air Force and Navy providing five and four, respectively.20 By mid-2023, however, it became clear that CYBERCOM would need to delay its plans. In particular, the Navy will not be able to deliver new teams for at least a few years because it needs to focus on improving the readiness of its existing cyber personnel.21

Moreover, even the existing teams have not actually reached FOC despite what CYBERCOM claims.

Evolution of CYBERCOM’s Authorities

While CYBERCOM has had the authority to conduct operations short of armed conflict outside of DoD-controlled networks since its creation,22 the Fiscal Year (FY) 2019 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) legislated the most important change in CYBERCOM’s authorities, defining cyber operations as a “traditional military activity,” and authorized DoD (and, by extension, CYBERCOM) to act in “foreign cyberspace to disrupt, defeat, and deter” cyberattacks against the U.S. government and the American people.23 This change allowed for more extensive planning and execution of cyber operations. The new authority also largely aligned with National Security Presidential Memorandum-13 (NSPM-13), a Trump administration initiative to streamline the process for authorizing military cyber operations.24 The Biden administration reportedly modified NSPM-13 but has largely kept it in place.25

CYBERCOM has also gained new acquisition authority and statutory responsibility for managing personnel. Previously, the services served as the executive agents for procurement for CYBERCOM, although CYBERCOM also possessed limited acquisition authority to execute contracts, with a $75 million annual cap. Then, in the FY 2022 NDAA, Congress took the unusual step of providing CYBERCOM with Enhanced Budgetary Control (EBC) to directly manage resources for equipping the CMF.26 These EBC authorities, which will take full effect this year, reflect congressional frustration with failures in the existing, services-led acquisition efforts on CYBERCOM’s behalf. As then CYBERCOM commander General Paul Nakasone explained to Congress in March 2023, the hope is that EBC will better harmonize CYBERCOM’s responsibilities and operations by providing it with control over funding for major acquisition programs.27

Nevertheless, the lion’s share of cyber funding in the FY 2024 budget remains with the services. CYBERCOM’s budget request is approximately $2.9 billion, while DoD’s total Cyberspace Activities Budget request for the services is $13.5 billion.28 Moreover, CYBERCOM will still rely on the services to spend much of the money that Congress appropriates.29

The promise of EBC was that it would bring CYBERCOM closer to the U.S. Special Operations Command (SOCOM) model, in which the force employer helps guide procurement. However, the services still retain the vast majority of cyber-specific funding, continuing CYBERCOM’s dependency on the services. The persistent structural problems render CYBERCOM unable to provide for itself. It continues to rely on the military services and, in some circumstances, the NSA for personnel, funding, foundational intelligence support, procurement and acquisition activities for cyber-specific capabilities, research and development for tools, and infrastructure supporting cyber operations.

Congressional Concerns About CYBERCOM’s Insufficient Maturity

Over the past five years, CYBERCOM has achieved important operational successes. It has conducted “hunt forward” operations at the invitation of allied and partner nations to help uncover and defeat cyber threats in their networks.30 It has also defended U.S. elections,31 responded to Iranian hackers in Albania,32 and helped Ukraine shore up its cyber systems following Russia’s 2022 invasion.33 However, these successes came despite, not as a result of, the U.S. military’s current organization for cyberspace operations.

Congress has repeatedly raised concerns about these issues. At a March 2023 hearing, Rep. Mike Gallagher (R-WI) noted: “Since 2013, Congress has tried to address force design and readiness through 24 different pieces of legislation. Twenty-four. And over that same period, we have tried to address the civilian and military cyber workforce dilemma 45 times; CYBERCOM acquisition matters, 12 times; and defense industrial base cybersecurity, 42 times.”34

Nearly every year for the past decade, Congress has requested information or reports about military cyber readiness — a clear indication DoD has been unable to satisfy congressional concerns. In 2016, Congress mandated that CYBERCOM launch an expedited two-year force-generation effort because the CMF had not achieved sustainable readiness.35 The next year, Congress requested briefings on cyber readiness shortfalls.36 In the FY 2020 NDAA, Congress required the secretary of defense to analyze the benefits and drawbacks of “establishing a cyber force as a separate uniformed service.”37 Two years later, Congress again called for an assessment of U.S. cyber posture.38

The FY 2023 NDAA directed the secretary of defense to study the services’ responsibilities for cyber force generation in light of “chronic shortages of proficient personnel in key work roles.”39 Among other issues, the study is supposed to explore whether a single military service should be responsible for force generation.

CYBERCOM implicitly acknowledged its force generation challenges in its May 2023 Strategic Priorities, vowing to improve readiness, recruitment, and retention.40 DoD, meanwhile, is developing a so-called “Cyber Command 2.0” initiative to address how the military generates and trains cyber forces.41 In December 2023, General Nakasone observed that the current state of U.S. military cyber organization is unsustainable. “I think all options are on the table, except the status quo,” he said.42

In Their Own Words: Gaps and Challenges in the Current Model

While force employment is the responsibility of CYBERCOM, responsibility for force generation is spread across the five military services. This system is failing to meet the unique demands of cyber-related training and acquisition. As one general officer lamented, “Our current strategy of relying on the existing Services to build the cyber expertise and capabilities required is inefficient, ineffective, and unlikely to succeed despite years of investment and the best efforts of our servicemembers.” Washington’s “only viable path forward,” the officer said, “is to establish a new Service focused on organizing, training, and equipping forces required to fight – and win – in cyberspace.” 43

Manning and training for cyberspace operations are not equivalent to furnishing infantry or logistics personnel. All specialties have distinct training and skill requirements, but the cyber domain requires a uniquely high level of technical training. As a result, individual cyber personnel can have outsized operational effects. As one lieutenant colonel in the Air Force noted, “10% of the [cyber] workforce provides 90% of the value.”

Additionally, acquisition processes for equipment and capabilities must move far more quickly than those for the other warfighting domains. Acquisition of software or exploits, for example, must occur rapidly to ensure they are not rendered obsolete.44 Moreover, many of the most cutting-edge capabilities reside within the private sector, including in industries not traditionally part of the defense-industrial base. Finally, there is a potentially greater role for non-uniformed civilian personnel in cyberspace capability development and employment.

The current system compounds these force-generation challenges. Each of the services has developed its own solutions, leading to both inconsistencies and shortcomings. As outlined below, these issues span talent recruitment and retention; occupational designations and training; promotions; critical support functions; administrative control; and capability acquisition.45

At root, the current readiness issue stems from the fact that none of the existing services prioritizes cyberspace. As a retired Navy captain observed, this fundamental mismatch “has yielded varying levels of fragmented support to cyber operations, [a] lack of continuity of cyber personnel, unclear career paths, insufficient experience, wide use of non-cyber personnel in cyber leadership positions, and cyber operations being treated always as a supporting entity across all services.”

The extensive interviews that inform this study provide the most direct and compelling evidence to date of the deficiencies in the U.S. military’s current cyber force generation model and readiness. They also help explain why the establishment of a Cyber Force is the best and only solution to these challenges. (See Appendix A for excerpts from the interviews and a demographic breakdown of the interviewees.)

Recruitment and Retention Shortfalls

The U.S. military is failing to recruit and retain enough talented cyber personnel. The “lack of talented personnel to fill positions on the Cyber Mission Force has been and continues to be a severely limiting factor for the overall force,” one Army colonel explained. A 2022 Government Accountability Office (GAO) report similarly concluded that all the services “continue to experience challenges retaining qualified cyber personnel.” Even the Army, which has fared better in the recruitment of skilled cyber personnel, has struggled to retain its cyber workforce.46

The current recruitment and retention shortfall stems from multiple problems, some of them inherent to the current system. First, the services are not using the tools at their disposal to bolster compensation for high-caliber personnel, nor are the services compensating them equitably. In addition, the services have inconsistent and poorly designed requirements governing how long their warfighters must serve. Worse, retention suffers from problems with service culture, leadership, and quality of life. The services’ promotion systems and CYBERCOM’s lack of administrative support also undermine retention, as discussed later in the report.

A Cyber Force would be far better equipped to recruit and retain cyber personnel, as the success of the Space Force has shown. Despite competing with private sector firms that offer more attractive salaries, the Space Force has not faced problems recruiting high-level talent.47 Because it is relatively small, the Space Force can selectively recruit highly skilled individuals rather than pursuing bulk accessions to fill the ranks like the larger services.48

SERVICES FAIL TO USE TOOLS AT THEIR DISPOSAL

To be fair to the services, the U.S. military is not the only one struggling to recruit cyber talent. There is a national shortage of cyber personnel, and the federal government struggles to compete with the private sector, which offers much better pay.49

Unlike the military, civilian government agencies use creative promotion schemes to ensure their cyber workforce is well-compensated, even if salaries do not match the private sector. The military also has some tools it can use to improve compensation, but the services are not using them effectively. For example, the 2022 GAO study found that the Army was not offering enlistment bonuses to cyber personnel.50

As one Army captain explained, CYBERCOM itself “is not able or empowered to use these options.” Meanwhile, “the service components responsible for manning CYBERCOM refrain from pursuing these choices aggressively because cyber is only one mission and not their primary charge.” A Cyber Force, by contrast, would naturally put cyber first.51

INCONSISTENT COMPENSATION

In addition to being inadequate, U.S. military compensation for cyber personnel is inconsistent across the services, damaging morale and esprit de corps.

Once the services recruit personnel, each service separately determines which ranks serve in which jobs. The Marines might assign a staff sergeant (E-6) to the same job the Air Force assigns a first sergeant (E-8). With different pay scales and incentives for these different ranks, the result is wide pay discrepancies between individuals performing identical work. Even when the servicemembers have similar levels of experience, compensation varies significantly. For example, the monthly salaries of two Interactive On-Net Operators (IONs) from different services, each with four to five years of experience, serving in the same location and performing largely the same job, may differ by more than $700.52 This discrepancy does not even take into account differences in housing allowances or pay incentives.

GAO studies have found that enlistment bonuses also vary dramatically across the services. Whereas GAO found in 2022 that the Army was not offering enlistment bonuses, the Marine Corps was offering $2,000 for cyber career fields, and the Navy was offering $5,000 with an additional $30,000 bonus after training completion.53

The services also use bonuses and incentives inconsistently and without regard for who is a worthy recipient. According to the 2022 GAO study, the services base retention bonuses for cyber personnel on their broader military career, not their unique skill sets.54 These findings matched conclusions from a 2017 GAO study.55 The persistence of these issues five years after the initial GAO study underscores that the services cannot fix these problems themselves.

INCONSISTENT AND POORLY DESIGNED LENGTH-OF-SERVICE REQUIREMENTS

Low cyber retention rates stem in part from inconsistent and poorly designed length-of-service requirements. Because each service has its own retention policies, they have distinct requirements for how long their servicemembers, including cyber personnel, must remain on active duty. What is more, these requirements do not adequately account for the “lengthy and expensive advanced cyber training” provided to cyber personnel, according to the GAO.56

For example, the Army usually requires officers to serve three times the length of their training. However, many advanced cyber training courses are not included in this Army regulation. As a result, personnel could attend an expensive year-long cyber training course and leave the military soon afterward.57 Until legislative intervention in 2023, the Marine Corps could not assign additional service obligations for lengthy and expensive cyber training.58

CULTURE

Many officers have described how service culture denigrates cyber talent, damaging the morale of cyber personnel and eroding retention.59 “Retention rates of cyber personnel are abysmal,” one retired Navy captain remarked. “The biggest reason the services hemorrhage talent is that cyber personnel do not feel valued by their service’s culture.” Similarly, a retired Army colonel shared, “I’ve seen senior warfighting leaders dismissively call cyber research ‘book reports,’ cyber operators ‘nerds,’ and cyber capability development ‘science projects.’” Only the creation of a new service dedicated to cyberspace can address these kinds of entrenched cultural challenges.

Inconsistent Career Field Designations, Skill Sets, and Training

Across the services, cyber-related career field assessments, assignments, designations, and skill sets60 are ill-defined and disjointed. This fragmented approach undermines training and personnel management.

INCONSISTENT AND INADEQUATE TRAINING

Currently, servicemembers arrive at CYBERCOM with skill sets that are not only inconsistent but also insufficient to fulfill their basic work roles. This problem stems from each of the services not only using different names for their cyber operators but also training them differently — without CYBERCOM’s needs in mind.

For example, when an Air Force cyber operations officer, a Navy cyber warfare engineer, and a Marine Corps cyber operations officer complete their initial entry training, they lack a common skillset (such as knowledge of specific operating systems or exploits). And none are qualified to serve in any of CYBERCOM’s basic work roles upon arrival.

In fact, it was not until February 2023 that the Navy began using a separate designation for its cyber warfare officers, in alignment with how the other services treat their cyber operations experts.61 While the Army and Air Force generally enable personnel to devote their careers to cyber roles, the Navy had been grouping cyber officers with intelligence and information warfare officers, hampering their ability to develop expertise.

The services train cyber personnel at service-specific training centers. Army centers include the Army Cyber School’s Virtual Training Area, the U.S. Army Cyber Center of Excellence, and Fort Eisenhower Signal Training Site. Air Force personnel train at the Air Force Cybersecurity University and the Cyberspace Technical Center of Excellence. The Navy has the Naval Information Warfare Training Center and the Naval Postgraduate School Center Cybersecurity and Cyber Operations. Finally, there is the Marine Corps Air/Ground Combat Center in California.

These centers do not have a common training system or set of standards. As one Navy captain noted, “Each service has developed their own training model and paths, which do have some overlap but for the most part are not synchronized.” They each have “different service-desired outcomes and minimal joint perspective when outside of CNMF roles,” the captain explained. “Without one overarching cyber service and related vision and clearly defined mission, cyber training will continue to produce an unbalanced and ineffective joint workforce where services will continue to prioritize efforts and service-specific career paths.”

A Navy lieutenant commander agreed. “Each of the services are [sic] training and employing cyber personnel to do the exact same jobs, such as exploitation analyst, tool developer, and cyber planner,” the officer observed. “Despite these identical needs, there is virtually no standardization whatsoever across the entirety of the military workforce. Each separate service maintains its own training programs, its own performance evaluation processes, its own employment metrics.” In short, “the totality of the force is wholly uncoordinated. From a mission perspective, I have witnessed firsthand how this situation creates impossible problems with regard to technical expertise and training.”

Many other officers discussed the lack of specialization in operating systems, intelligence, exploits, and other techniques associated with cyber-related personnel across the services. Instead of offering specialized training, the services provide general coursework, teach capabilities at a high level of generality, and require operators to learn a broad range of system architectures rather than honing their skills on a specific system. This is like requiring Air Force pilots to learn a bit about all types of aircraft in the fleet rather than specializing in the particular craft they will pilot.

Figure 2 contrasts CYBERCOM-defined work roles with service-specific cyber career field designations and titles for both officers and enlisted personnel.62 There is little overlap between the two. Furthermore, the service-based training with each military occupational specialty (MOS) does not slot into any particular CYBERCOM work role.

Compared to the other warfighting domains, the U.S. military spends relatively little time and money on training for cyber officers. The initial cost of training an Air Force fighter pilot ranges from $5.6 to $10.9 million, and the annual cost of training for a Naval aviator is $2.2 million, according to a RAND report.63 By contrast, the GAO found that the training and subsequent certification to become an interactive on-net operator costs between $220,000 and $500,000.64

The GAO also found that courses are “not listed in regulation or in Army or joint training systems of record.” There are long breaks between courses, and the length of the courses themselves fluctuates. In addition, there are often significant delays between when candidates are nominated for training and when they attend.65

Across the services, there is also a lack of continual training for the officer corps. An April 2023 paper published by the National Defense University concluded that the cyber domain requires continual training with some technical training delivered every 18 to 24 months.66 Although servicemembers often have the opportunity to attend graduate school, such courses are also not well suited to technical training for a dynamic, rapidly changing field. Such courses are also different from the more specialized cyber upskilling needed to create effective leaders.

INABILITY TO MANAGE CYBER PERSONNEL

Because the services do not designate personnel for particular CYBERCOM work roles, “military service officials cannot determine if specific work roles are experiencing staffing gaps,” the GAO concluded. Put simply, the services do not know if they have “the right personnel to carry out key missions.”67

Likewise, there is no system or method to track individuals with cyber skills as they transition to and from the services and CYBERCOM. This means a servicemember may enter with initial training for a cyber-related career field but could be moved to a non-cyber career track during one of these transitions. Such reassignments stem from the reality that the services understandably prioritize their unique needs and missions, which may not allow for individual personnel to stay on a cyber-specific track for the duration of their career.68

Promotion Processes Do Not Reward Technical Competence

The services determine promotions for their cyber personnel, but they use systems designed for the non-cyber world. These systems reward command experience — usually in non-cyber fields — over technical competence. As a result, the services are replete with commissioned and non-commissioned officers who may be good leaders but lack the cyber-specific skills and experience necessary to excel.

Standard service processes require an individual to have held certain positions to be promoted. These roles are often entirely unrelated to CYBERCOM priorities. In the Army, for example, a lieutenant must serve as a platoon leader before being promoted. But many technically proficient cyber operators never hold the positions deemed necessary for advancement. Consequently, they are passed over for promotion, while those without cyber expertise are placed in command.

Compounding this issue, the personnel in charge of the promotion process within each service typically lack the requisite cyber knowledge to make effective promotion decisions. A U.S. Army colonel noted that the individuals on service promotion boards struggle to differentiate between “officers with advanced, skilled degrees in computer science from esteemed institutions” and “those who received online degrees in information management. … This is akin to equating a brain surgeon with a field medic.”

It does not have to work this way. The Space Force provides an illustration. As a first lieutenant in the Air Force explained, the “Space Force gives the best-qualified commanders the best-qualified experts (long-time members who have reached the major, lieutenant colonel, or warrant officer levels), and those experts retain the ability to work a technical role while still benefiting from career progression.” By contrast, the current promotion system for cyber “robs all highly technical career fields of their most qualified experts, as our antiquated career progression system demands they go on to command something rather than do their best work at the keyboard.”

The current promotion system creates real risks to U.S. security. In a June 2023 military journal article, Navy Reserve Lieutenant Commander Eric Seligman notes that officers without cyber warfare experience struggle to assess the risks stemming from cyber operations. They face decision paralysis, improperly staff subordinate positions, and often fail to employ technical solutions necessary to achieve operational and tactical objectives. They also have difficulty translating doctrine into action, distinguishing good from bad operational and tactical advice, and predicting enemy maneuvers.69

As Seligman argues, a doctrinal and policy-focused understanding of cyber warfare is no replacement for hands-on experience. It would be like an officer who has “been trained on the concept of the rifle and its potential effects on the enemy” but never actually fired one.70 Marine Corps officers stand by the tenet, “Every Marine a rifleman.” No Navy SEAL would follow an officer into battle if that officer did not go through BUD/S training. However, cyber operators and junior officers today follow the orders of a mostly inexperienced senior officer cadre. A Marine Corps captain concurred, “Leading in the cyberspace domain demands technical competency that cannot be taught in a 12-month schoolhouse alone.” He added, “Under no circumstances would a cyber officer be asked to lead a squadron of aircraft, and yet the opposite is often true.”

Indeed, interviewees for this project cite numerous examples of senior officers who have little to no experience in the cyber domain — even though the services have had 13 years since the creation of CYBERCOM to develop qualified senior leaders. Of the U.S. military’s more than 45 general and flag officers involved in cyber as of summer 2023, fewer than five had any technical experience in the cyber domain.71

CYBERCOM today has promotable talent, but the military is not properly utilizing it. A Marine Corps captain stated that he “personally had career setbacks because (he) pursued a master’s degree in computer science instead of a military war-college certificate.”

The current promotion system creates a vicious cycle. Potential cyber leaders cannot look to their superiors for mentorship or wisdom gained from experience within the domain. Facing disincentives to the further development of their skills, talented cyber officers choose other paths or exit the military altogether, depriving the next generation of cyber-experienced leadership.

Lack of Administrative, Intelligence, and Mental Health Support

CYBERCOM lacks many of the dedicated support functions that other unified combatant commands enjoy, including foundational intelligence support for operations, administrative support, and medical support, especially for mental health.

ADMINISTRATIVE SUPPORT

Too often, CYBERCOM’s few qualified cyber operators are pulled away from operational responsibilities to handle administrative functions because the services provide CYBERCOM with inadequate administrative support. “Very few capable analysts can dedicate a significant amount of time to the operational mission,” a U.S. Air Force major commented. “Less than 10 percent of team members have been on the team for over a year,” placing a significant burden on the few experienced analysts to both execute operations and train new personnel. The CNMF’s elevation to a sub-unified command in December 2022 partly resolved this issue, but the CNMF is only one-third of the CMF. The other teams continue to lack administrative support.

The administrative burden foisted onto cyber operators undermines talent retention. A 2019 internal survey of the U.S. Army Cyber Command workforce found that “a factor in their decision to leave after their contracts or service obligations expired was their inability to focus on the mission or tradecraft (i.e., time spent on keyboard) due to the constant distractions from administrative requirements.”72

INTELLIGENCE SUPPORT

Cyber reconnaissance and targeting support are essential to the effectiveness of offensive cyber operations but CYBERCOM currently receives inadequate intelligence support.73

Like all combatant commands, CYBERCOM does have a Joint Intelligence Operations Center, which provides operational intelligence for force employment. Cyber operations, however, lack a dedicated all-source cyberspace intelligence center to collect foundational, ongoing intelligence about adversary cyber capabilities and order of battle. The U.S. military does have such centers for other warfighting domains, such as the Army’s National Ground Intelligence Center or the Navy’s Office of Naval Intelligence. These centers address standing intelligence requirements about adversary capabilities and strategies. Last year, the outgoing commander of CYBERCOM’s Joint Intelligence Operations Center called the absence of a comparable center for cyber intelligence a “gaping hole.”74

In 2023, CYBERCOM announced it would establish a foundational cyber center in partnership with the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) and NSA. In effect, CYBERCOM attempted to build a service-like capability to remediate the gaps stemming from the absence of an independent cyber service. The final version of the FY 2024 NDAA, however, did not include the proposed provision to establish such a center.75

If such a center were established, it would likely suffer staffing shortages unless the United States also creates a Cyber Force. The resourcing and staffing for existing intelligence entities usually falls to the parent service. While the DIA (or others) could be charged with managing the center, it would fall to the existing services to provide trained and qualified personnel, who would likely face the same training and skill development issues described earlier.

MEDICAL SUPPORT

Cyber operators work in intense environments but are not afforded the same downtime as their counterparts in other fields.76 Mental health initiatives exist across the DoD, including for Special Operations Forces, pilots, and operators involved with unmanned aerial flight operations.77 However, there are no programs for the distinct challenges faced by cyber personnel.

Without an understanding of the work roles and tasks of cyber operators, the services (and specific commanders) may not appreciate the need for mental health services. One officer shared his troubling experience: “I think many folks in military cyber have been struggling with inexperienced leadership. But in [my service], those put in charge of cyber units can be downright hostile to technical cyber officers. For example, how about getting retaliated against by your [commanding officer] and your chain of command simply for going to mental health [treatment]? That thing they said in the yearly [general military training] about how going to mental health won’t affect your clearance … it happened to me.”

Service Control and Service-Related Requirements Degrade Full Operational Capability

“Years of investment and training are lost when servicemembers are moved away from the cyber mission,” a general officer lamented. But because the services retain administrative control over cyber personnel assigned to CYBERCOM, the services can pull them out for service-related requirements unrelated to their cyber roles. This is one important reason why CYBERCOM was unable to get all 133 CMF teams up to FOC status and why it is so difficult for teams to maintain that status.

A lieutenant colonel in the U.S. Army Reserves, speaking from personal experience at the CNMF, observed a “general tension” between the administrative control and operational control commands. “[W]e are forced to pull servicemembers away from operational tasks to instead conduct service-related activities … This is a systemic problem that, in mine and others’ opinions, hurts retention, as it undermines morale,” the officer said. Administrative control commanders “often create requirements at the expense of the mission. There are well documented times when units have closed down joint mission areas en masse to conduct unit events.”

An Air Force major shared a similar experience: “In one instance, a group commander required a 12-week ‘life skills’ course that taught new airmen how to cook, how to date, and how to be emotionally healthy. Meanwhile, the mission was manned at less than 60 percent.” The major said, “Another commander cited an ‘unwritten rule’ stating that he only owed the [NSA] 80 percent of his airmen’s time and the other 20 percent belongs to the USAF.”

In addition to impinging on cyber operators’ time, the services can also rotate them to different, non-cyber assignments. As one Army colonel explained, “Upskilling talent is hard, takes years, and as soon as someone reaches a threshold, the service rotates that person out of the team and back to a service assignment … The demands within the services are continuing to pull talent away from the CMF.”

THE SERVICES’ FOC SHELL GAME

By 2018, all the existing CMF teams had officially reached FOC, meaning they were supposed to have sufficiently trained and equipped personnel to execute their missions.78 Yet fewer CMF teams are actually at FOC than official metrics indicate.

First of all, the services have not recruited and trained enough cyber personnel to fill 133 teams. As an Army colonel noted, “The lack of talented personnel to fill the positions on the teams has been and continues to be a severely limiting factor for the overall force. From the onset of U.S. Cyber Command, [the] services focused on recruiting, retaining, and filling teams to reach fully operational capable (FOC) status. Once teams achieve FOC, they often filled between 67-75 percent capacity.” As a result, teams that are officially considered to be FOC are not, in reality, at 100 percent strength.

According to multiple interviewees, proficient cyber operators are double-counted to make it appear like all the teams are at full strength. The services “play a shell game [with their] top tier talent,” one Army major warned. “It is a common occurrence that the same 50 people are constantly task-organized from across the force to solve any and all of the command’s hardest problems.” An Army captain gave a similar account of how his service initially brought its cyber teams up to FOC: “The Army’s rush to get teams to Full Operational Capability (FOC) was built on a farcical shell game in which the same personnel were moved from recently certified teams to new teams until all teams had certified. Yet few are able to provide capability if asked.”

An Army Reserve major similarly said that U.S. Army Cyber Command “consistently bent numbers, changed interpretations, and moved soldiers from team to team, or mission element to mission element, to paint the picture that teams were both fully manned and fully trained.” In fact, the officer said, “most [Cyber Protection Teams] never exceeded 75 percent of their intended manning and relied on a core squad of fully trained people cleverly assigned to launder the reality that most soldiers were not fully trained.” This deception “was compounded by unrealistic training timelines.” U.S. Army Cyber Command “issued demanding deadlines to reach FOC, and lower-level commanders would then force timelines to move even faster — presumably to maximize their personal performance evaluations.” The result was an “environment that incentivized exaggerating how many soldiers and [Cyber Protection Teams] were FOC and disguising our numbers to higher headquarters.”

Acquisitions Challenges

Across the U.S. military, it takes an average of 10 to 15 years to field a new capability.79 Yet in the cyber domain, tools are frequently updated and rendered obsolete within a year or two of development (if not sooner). Nevertheless, the services continue to enjoy a preponderant share of the budget and acquisitions authority for cyberspace even though they have not adapted to meet CYBERCOM’s timeline for tool acquisition. Thus, CYBERCOM is stuck with out-of-date capabilities and is forced to borrow the NSA’s tools, explaining why assessments continue to conclude that severing CYBERCOM from the NSA would have detrimental effects.

Recognizing this problem, Congress has intervened several times to grant CYBERCOM greater control over the acquisition of capabilities, resulting in incremental changes to ameliorate this issue. However, this solution runs contrary to civilian oversight of acquisition, which services have and CYBERCOM does not.

In the FY 2016 NDAA, Congress granted CYBERCOM authority for the development, acquisition, and sustainment of cyber-specific equipment and capabilities.80 The following year, Congress amended DoD’s special emergency procurement authority to facilitate defense against and recovery from a cyberattack.81 As a result of more recent congressional direction, CYBERCOM in 2027 will assume “service-like acquisition decision authority” over platforms that the command uses to conduct cyber operations.82

Since the passage of the FY 2016 NDAA, CYBERCOM has been able to hire some acquisition professionals, but it continues to outsource most contracting, as the services make the large purchases on its behalf.83 The director of CYBERCOM’s acquisitions directorate said that since Congress granted the command EBC, he hoped to hire 40 people in 2023 and up to another 50 in 2024. But this is still a fraction of the personnel required to manage a $3 billion budget. In comparison, the Army boasts that its acquisition workforce “is composed of approximately 32,000 civilian and military professionals,”84 or about one person for every $6 million of discretionary budget.

Despite CYBERCOM’s acquisition authorities and EBC, the lion’s share of funding for cyberspace activities remains with the services. The services, however, lack a unified process for spending money on cyber-related capabilities, equipment, training, and education. This leads to redundant and disparate efforts, not effective preparation for joint warfighting. As a major in the U.S. Air Force noted, “The services and the other combatant commands have taken it upon themselves to acquire their own cyber capabilities to meet their needs, resulting in vast duplication and reliance on defense contractors to provide questionable and often self-serving operational guidance.”

Another Air Force major similarly shared:

I’ve witnessed vendors sell the same $100M offering to two services under a different name so those services could independently lobby for resources. I’ve witnessed one service sabotage another’s cyber operation (both under the same ‘Joint’ Force Headquarters) simply because that service did not receive credit. I’ve seen the services’ acquisition communities spend over $1B on poorly defined and duplicative cyber requirements to deliver tools that will never be used. Every effort to unify resources and address national priorities is undermined and resisted by the services who perceive no benefit to their domains.

All of this ultimately reduces force readiness. Without the correct equipment, even the best-trained cyber warrior cannot be effective in conflict. Moreover, the ongoing effort to transfer acquisition authority to CYBERCOM, while borne out of a legitimate frustration with the status quo, will result in the removal of traditional civilian oversight of acquisition, which only the services can provide.

Counterarguments to Establishing a U.S. Cyber Force

Some experts who acknowledge the force-generation challenges facing CYBERCOM nevertheless oppose the creation of a Cyber Force.85 They offer four main arguments against creating an independent, uniformed cyber service.

Counterargument 1: A Cyber Force will negatively impact readiness in the short term and create budgeting and personnel problems for the other services.

This critique posits that creating a Cyber Force would deprive the services of critical personnel. Transferring capable IT and cybersecurity professionals now focused on network architecture and the defense of internal service systems to the Cyber Force would leave the services bereft of skilled personnel. However, shifting only CMF billets, which do not include the services’ IT and cybersecurity personnel, would render this potential issue moot.

A related objection argues that transitioning personnel and budgets to the Cyber Force from multiple services would impose an insurmountable administrative burden. Prior to the establishment of the Space Force, the preponderance of space-related personnel and investments were already housed within the Department of the Air Force. But cyber-focused personnel and funding are currently much more dispersed.86 While this is true, all services have existing methods for inter-service transfers. By streamlining these transfers, the Space Force acquired more than 13,000 servicemembers and civilians in its first two years.87

Counterargument 2: The Space Force should be responsible for force generation for cyberspace.

Some commentators argue that DoD should combine cyber and space operations under the control of the Space Force. Those who favor this position tend to believe a service’s value is based at least in part on its size. At present, the Space Force is small but set to grow from 8,400 to 16,000 uniformed and civilian Guardians and may continue to grow based on the importance of space operations.88 More to the point, however, this critique ignores the fact that a small number of highly skilled operatives can be effective in cyberspace.

The argument also presumes an inherent link between space and cyberspace. Space assets, such as communications satellites, indeed serve a critical function in the transmission of information. Likewise, many ground operations and weapons systems are also dependent on space assets, but this does not mean the Space Force should train personnel for ground operations. As distinct operational domains, space and cyberspace have unique “man, train, and equip” requirements.

Counterargument 3: The SOCOM model is a better fit for cyberspace than a Cyber Force.

Perhaps the most common counterargument to the creation of a Cyber Force is that CYBERCOM should apply the SOCOM model to cyberspace — notwithstanding SOCOM’s own growing pains over its 30-year history.89 However, while SOCOM and CYBERCOM both possess highly skilled operators, they are otherwise very different.

In the SOCOM model, each of the services provides the force employer — SOCOM — with expert personnel who possess skills suited to their particular domain. For instance, an Army Ranger trains for special operations on land, while Navy SEALs possess skills tailored to maritime special operations. Rangers and SEALs are not interchangeable. The Army cannot train SEALS, nor the Navy Rangers. Thus, SOCOM actually gains strength from this one-of-a-kind distributed force-generation model.

However, there are no land, sea, or air-specific cyber functions that only particular services can provide. As one U.S. Navy captain noted, SOCOM’s “success is achieved by allowing each of the service-specific commands to specialize in discrete types of warfare, technologies, and operational environments.” By contrast, as a retired Navy captain noted, “Cyberattacks will not be, nor are they currently, service-specific nor sector-specific, so it does not make sense to have created service-specific mission teams, different designators, MOSs, etc., to respond to the broad scale of cyberattacks.”

A side-by-side comparison of the SOCOM and CMF structures depicts two wholly different organizational architectures, as illustrated in figures 3 and 4. SOCOM’s organization into many sub-unified commands and geographic commands does not reflect the requisite structure of CMF and its component parts.

SOCOM has also faced the same challenges as CYBERCOM regarding drawing personnel from disparate services. The services’ inconsistent definitions of overlapping skill sets create incompatibility. This makes interoperability challenging, particularly in dynamic, high-operational-tempo environments. Although the defense community is largely content with the way SOCOM is organized, led, and operated, a GAO report from October 2022 noted that SOCOM has its own challenges concerning oversight and command and control.90 For SOCOM, a dependence on multiple services makes some of these challenges unavoidable, yet the U.S. military has a better option for cyber force generation.

Counterargument 4: CYBERCOM should absorb many of the man, train, and equip responsibilities from the services.

Rather than creating a Cyber Force, some argue that CYBERCOM should evolve to absorb the force-generation responsibilities from the other services. This approach would be tantamount to carving out an exception for cyber-related military matters from the 1986 Goldwater-Nichols Act, the landmark legislation that drew the line between force generation and force employment.

In this scenario, the commander of CYBERCOM would become responsible for military cyber force generation and force employment in addition to his or her duties as head of the NSA. While the dual-hatted structure for CYBERCOM and the NSA was initially intended to be temporary, it remains advantageous, as concluded by a December 2022 study led by General (Ret.) Joseph Dunford, former chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.91 The study, however, conceded that simultaneously leading both organizations is a significant amount of work for one individual. Adding what would effectively be a third hat — force-generation responsibilities — would leave the commander less time for the other two, or even force DoD to sever NSA from CYBERCOM.

What Should a Cyber Force Look Like?

Many of the challenges outlined in the section above could only be solved or at least significantly mitigated through the creation of the Cyber Force as the force generator for the cyber domain. CYBERCOM would remain the force employer. This new Cyber Force could be located within the Department of the Army, just as the Marine Corps is housed within the Department of the Navy and the Space Force sits within the Department of the Air Force.

Standing up this new service would be relatively straightforward. Initially, the Cyber Force would encompass the billets that currently comprise the CMF: a 6,200-person mission group consisting of servicemembers, civilians, and contractors (see Figure 5).92 Beyond the CMF, the Cyber Force could also absorb a select number of billets for cyberspace operators that currently fall within the SOCOM enterprise.

In addition, the Cyber Force would require the transfer (or addition) of support staff billets and infrastructure. The services would likely need to retain some cyber support staff, but a percentage of the cyber-specific force-generation billets from each of the services would transfer to the Cyber Force, particularly those necessary for Cyber Force training institutions. And some Cyber Force recruitment of existing servicemembers would be necessary to fill the remaining gaps in support staff. This shift, however, should not strain the resources of any one service. In total, the Cyber Force would probably initially comprise approximately 10,000 personnel, although this number would likely grow over time as cyber threats continue to expand.

The Cyber Force could draw on lessons from the Space Force, which has encountered few issues filling its new roles even though it requires highly technical and skilled personnel.93 At a leadership level, the Space Force’s establishment mostly required the lateral transfer of personnel from Air Force Space Command.94 The Space Force, which currently has 8,400 billets, attributes much of its recruiting success to being small, agile, and selective with applicants. Its leaders understand they do not need to mimic the larger services.95 To boost recruitment, the service has also taken advantage of opportunities for the direct commissioning of civilians with requisite skills for space.96

Most importantly, the creation of a Cyber Force would not require an extensive or complex shuffle of personnel, and the services would retain defensive cyber personnel and IT infrastructure management capabilities for the DoD information networks (DODIN). The creation of a Cyber Force, however, would preclude service-retained personnel from conducting offensive cyberspace operations. Figure 6 illustrates proposed responsibilities of the Cyber Force and the services.

An initial budget for the Cyber Force would be approximately $16.5 billion, a fraction of the hundred-billion-dollar budgets of the Army, Navy, and Air Force. This estimate includes DoD’s current allocation for the cyberspace activities budget ($13.5 billion), minus the cybersecurity investments from the services ($511 million). The budget estimate also includes the resources currently carved out for CYBERCOM under EBC (about $2.9 billion), the military personnel funds ($624.25 million), and training resources.97 An apt comparison is the budget for the Space Force, for which DoD requested $30 billion for FY 2024.98

While the other services may see a slight reduction in their budgets after the creation of a Cyber Force, most of the decrease would come from a reduction in cyber force generation costs thanks to efficiencies from eliminating redundancies. The Cyber Force would consolidate the acquisitions process specifically for operational capabilities. It should not, however, become the IT and communications service provider for the services, a role that would distract it from operational priorities.99

Creating a Cyber Force would also benefit the NSA.100 A quarter of the NSA’s workforce comprises active-duty military units, currently provided by the services. However, these units are not held accountable for successfully serving the NSA’s mission. With a Cyber Force focused on delivering well-trained cyber personnel, the NSA would, in turn, receive more, high-quality, human resources.

During a visit to Navy Information Operations Command Pensacola, then deputy commander of U.S. Cyber Command Lt. Gen. Timothy Haugh, engaged in cyber discussions with Sailors on Oct. 12, 2023.

A Cyber Force would also facilitate the establishment of more robust legal principles for cyberspace. Military leaders and commanders have long required legal advisors for the specific domains in which they operate. The DoD legal community, in turn, has training, education, and experience tracks to develop attorneys who deliver this legal support. Yet unlike land, sea, air, and space, cyberspace is an interdependent global domain, entirely human-made, and consists largely of privately owned and operated systems. The current reliance on non-cyber lawyers serves U.S. cyber operations poorly.

If done properly, the overall readiness of the military’s cyber forces should not suffer during a transition to an independent Cyber Force. Instead, cyber forces would gain more operational focus and direction while consolidating acquisition processes and maximizing budgetary effectiveness.

Conclusion

Years after designating cyberspace as a warfighting domain, leaders must acknowledge the writing on the wall. The scope and scale of cyber threats are growing. Cyberspace plays a central role in China’s strategy as the “pacing threat” for the United States. China has already centralized its cyber, space, electronic warfare, and psychological warfare capabilities within its Strategic Support Force. Russia is actively leveraging cyber operations both on the battlefield and to threaten U.S. critical infrastructure and interfere in American politics.

Conventional wisdom holds that the U.S. military is well positioned to dominate in the cyber realm given CYBERCOM’s current resources, capabilities, and authorities. However, recent congressionally mandated studies,101 independent analyses and audits, and the accumulated personal accounts from current and retired servicemembers demonstrate otherwise.

Previous attempts to increase U.S. cyber force readiness have failed. Measures such as the elevation of CYBERCOM to a unified combatant command, the promised expansion of the CMF, and the delivery of EBC do not address major underlying force-generation problems. U.S. policymakers must acknowledge the difficult reality that the military has tried and failed to salvage the status quo.

This failure stems from the basic fact that non-cyber services are responsible for cyber force generation. The solution is to create an independent, uniformed Cyber Force. While many experts have long called for the creation of an independent Cyber Force,102 policymakers should especially listen to the voices of those servicemembers with direct, extensive operational experience. The numerous first-hand accounts highlighted in this monograph offer a compelling testament to the need for an independent service for cyberspace.

The United States has a limited window of opportunity to reorganize, allocate resources, and develop sustainable cyber force readiness. The U.S. military has failed to fix the problem on its own. Only Congress can create a new independent service, so it is time for lawmakers to act.

No comments:

Post a Comment