Natasha Hall

Human civilization was born out of the Middle East’s waterways. As ancient cities grew from thousands to millions, agriculture also expanded to support livelihoods, trade, and food security.

Human civilization was born out of the Middle East’s waterways. As ancient cities grew from thousands to millions, agriculture also expanded to support livelihoods, trade, and food security.Today, the Middle East is facing a water crisis.

Decades of poor water management, exploding populations, and rising temperatures have degraded the region’s land and sapped its limited water supplies. The region’s famous waterways are disappearing before our very eyes. Once-roaring rivers have been reduced to trickles that can easily be crossed on foot.

By 2050, every single country in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) will live under extremely high water stress.

If temperatures rise by 4°C, the region would experience a 75 percent drop in freshwater availability, and many countries in the region are expected to warm about 5°C by the end of the century.

Countries that are most vulnerable to climate change and the least ready to adapt are also those affected by conflict. Countries like Syria, Yemen, Iraq, Lebanon, and Jordan are either embroiled in their own conflicts or affected by violence in neighboring countries.

Water insecurity most endangers these conflict-affected countries, but those crises can spill across borders.

As a result, failure to improve water management and adapt to a changing climate threatens both regional and international security.

Many Middle Eastern governments are confronting unprecedented levels of corruption, violence, debt, and unemployment. That makes them especially vulnerable.

They must grapple with rising levels of water insecurity at a moment when the energy transition away from fossil fuels has combined with donor fatigue to shrink public coffers and divert international attention away from the region.

On top of these challenges, climate-related water scarcity is projected to reduce GDP in the Arab states by as much as 14 percent by 2050.

Despite the urgency, governments and other stakeholders continue to pursue the unsustainable water management practices of the past. Reform is difficult due to decades of unsustainable behaviors and policies that have been entrenched for generations. Understanding how these countries got to this inflection point is critical for implementing politically feasible reforms.

Era of Expansion

Farmers work in a rice field in Qalyubia governorate.

In the 1950s, the Middle East was positioned for dramatic change. Abundant energy resources, foreign assistance, and expansive irrigation projects drove development in arid regions and deserts. Populations boomed, and living standards rose. Water consumption exploded.

From 1950 to 2000, the MENA region’s population almost quadrupled from around 100 million to 380 million, growing faster than every other major region in the world.

Times of plenty led to an expansion in agriculture. Irrigated land rapidly increased.

When ambitious government agricultural polices combined with population growth, renewable freshwater resources began to decline precipitously.

In a post-colonial Middle East, governments sought self-sufficiency, rapid economic growth, and modernity. Those instincts drove the desire to expand and control water resources.

Governments built hundreds of dams, some of which ranked among the world’s largest.

Beyond the hydrological needs they were designed to meet, dams represented the region’s power and potential. Egypt’s Aswan High Dam became not only about controlling water, but about sovereignty.

Famous Egyptian singer Abdel Halim Hafez in concert in 1974. | Daniel SIMON/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images | *This song "حكايه شعب" is translated by the authors from the original Arabic.

Under the glimmering surface of seemingly endless expanses of water, tensions loomed.

Water tables were falling, stored water was evaporating at increasing rates, and subnational and transboundary tensions were rising.

But the rush to construct dams continued into the twenty-first century, driven by a strategy that prioritized near-term wins and sovereignty over sustainable cooperation.

As a result of today’s scarcity, regional transboundary tensions run higher than ever. By 2021, conditions had nearly reached “dead pool” in downstream dams in Syria along the Euphrates, meaning the reservoir level had fallen too low to flow through the dam. Further south, Syria consistently failed to deliver promised levels of water to Jordan’s Unity Dam, passing on to Jordan many of the same shortfalls that Turkey inflicts on Syria.

Al-Wehda Dam, or Unity Dam, in Jordan.

Governments continued to search for water to meet the unsustainable demand they created.

Many states provided diesel subsidies, allowing farmers to pump groundwater from ever-greater depths. By the 80s and 90s, groundwater in Syria, Jordan, and Yemen was being tapped at an unsustainable rate.

Changes in Groundwater Storage in the Middle East and North Africa between 2002 and 2023 (cm)

Era of Thirst

Drought ravages Iraq's southern marshes.

Today, the region is suffering from these decades of unsustainable expansion. Dams and agricultural policies have dried up legendary waterways and former oases. The Tigris, the Euphrates, and the Jordan Rivers became just a trickle of their former flow.

Untreated wastewater, gray water, and agricultural runoff have exacerbated scarcity by contaminating limited freshwater supplies.

Buffaloes in the suburbs of the city are cooling their bodies in the sewage water by the Shatt al-Arab River.

Today, from above and below, pollution and salinization are encroaching on what little freshwater remains.

In Jordan, Yemen, Syria, Lebanon, and Iraq, many aquifers are no longer potable. In Gaza, the water that comes out of the tap is brackish and contaminated. The coastal aquifer upon which Palestinians and Israelis depend is undrinkable from overpumping and wastewater contamination. In Syria, the fluoride concentration of groundwater resources has reached toxic levels.

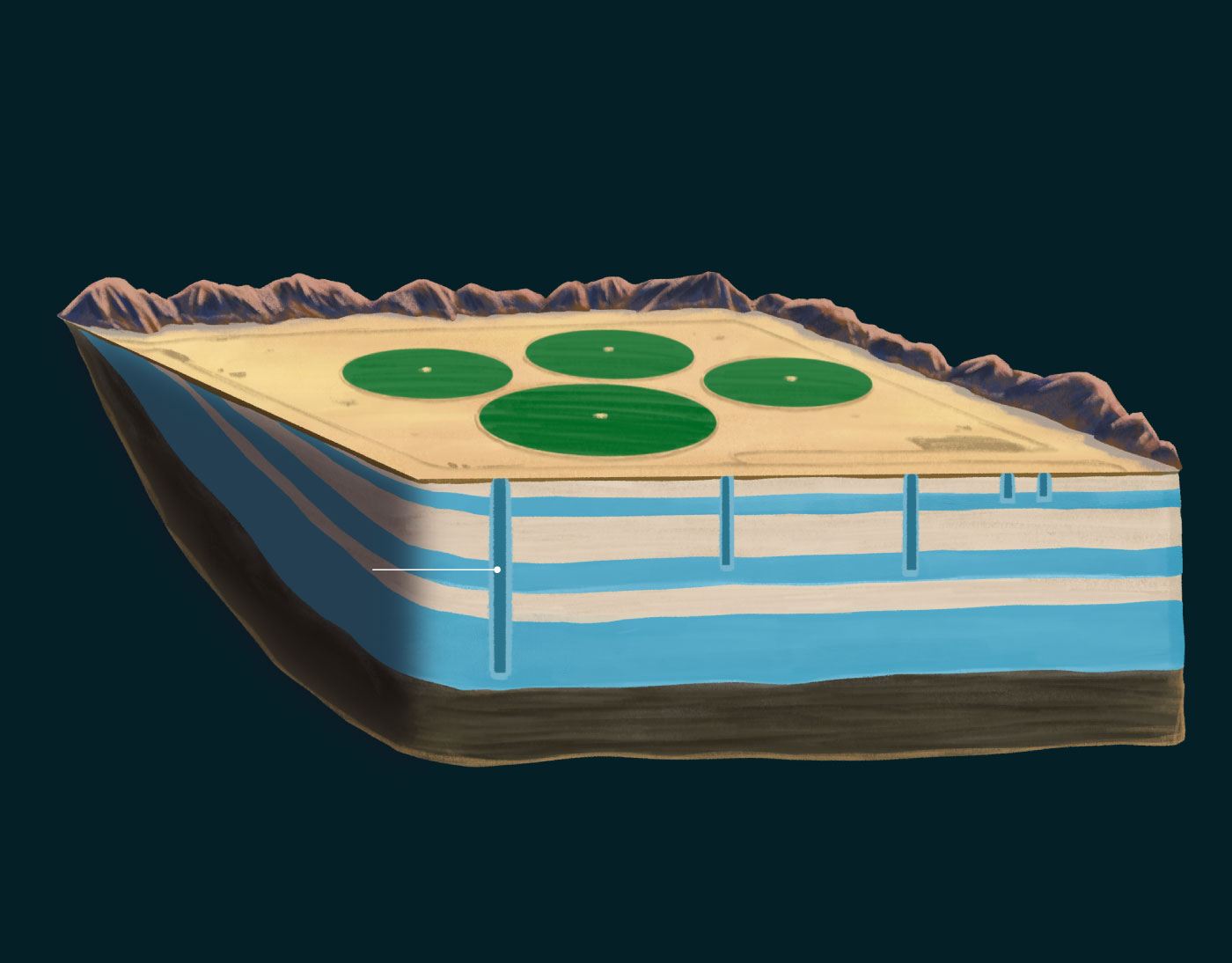

The Dangers of Overpumping Aquifers

MENA countries tap shallow and deep aquifers for irrigation needs. However, current levels of water usage far outpace renewal capabilities.

As water availability shrinks further and water utilities deteriorate, water provided by the government is still cheap—but there isn’t enough, and it isn’t safe to drink. Customers need to buy expensive water from private companies, even in the poorest parts of the Middle East.

Before a UNICEF water project reached communities in Sa’ada, Yemen, in 2023, the price of water reached 10 USD per cubic meter. By comparison, Germans—whose average annual income is more than 100 times the average Yemeni’s—pay about one U.S. dollar per cubic meter for the safe water that runs out of their taps.

Residents of Taez, Yemen, collect water from a tanker truck on June 8, 2023.

Even trucked water isn’t always safe. It’s often not monitored or regulated, and it sometimes comes from illegal wells, further depleting groundwater. As a result, waterborne illnesses such as cholera are making a comeback. In 2017 and 2019, respectively, Yemen accounted for 84 percent and 93 percent of all cholera cases worldwide.

As water availability shrinks, populations are living on less and less water. Researchers often use the metric of daily water usage to assess a population's access to water for basic needs, but the reality is far starker for many populations than average per capita water withdrawals would suggest.

Water availability for the region's poor and displaced is even more dire.

For context, the average American uses around 380 liters per day.

An eight-minute shower uses 65 liters.

Handwashing a day’s worth of dirty dishes uses around 76 liters.

Policies are not keeping up with urgency of the matter. The percentage of water lost through leaks and theft—what water experts call “non-revenue water”—is remarkably high: about 50 percent of all water in Jordan, and far higher in certain parts of the country. Neighboring countries don’t have good data, but many think the situation there is even worse.

And even though agriculture is a shrinking part of many Middle Eastern economies, it remains a huge user of water.

Faced with growing scarcity, local authorities are forced to cut people off from water. While the Iraqi government once provided diesel, water, seeds, fertilizers, and pesticides at a subsidized rate or for free, the Iraqi Ministry of Agriculture slashed irrigation for agriculture by 50 percent in 2022. Across the border, the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria has rationed water for farmers and limited them to sowing 25 percent of their land for certain crops.

Those dependent on the flailing agricultural sector then struggle to find work elsewhere.

Without a safety net, many people move to cities in search of opportunities. But governments are struggling to accommodate rapid urban growth. Unemployment is already in the double digits throughout the region.

Cities, failing to absorb newcomers, often criminalize them instead.

In 2017, Asaad Abdulameer al-Eidani ran a successful political campaign for the seat of the governor of Basra Province in Iraq with rhetoric marginalizing these outsiders. After he won, he restricted legal residency in the city to those with proof of homeownership and claimed that Iraqi “immigrants” to Basra were responsible for all the crimes in the city.

Despite this resistance, urbanization and further displacement are only expected to increase with climate change, as precipitation variability and evaporation rates are already high.

The region is running dry.

The costs of business as usual are mounting daily, but there is a way forward.

The Way Forward

Generations of unsustainable water usage have become entrenched in the social, political, and economic fabric of societies.

To avoid shaking the delicate relationship between governments and their citizens, water-related projects have tended to focus on stopgap measures that increase supply, not holistic reform. Some regional governments seem to be waiting for technology or desalination to save them. But most experts agree that desalination is too expensive and energy-intensive and has too many potential environmental consequences to provide for all of a country’s water needs.

Technology is also unlikely to solve the problem alone. For example, some countries have installed powerful tools like SCADA (Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition) systems that allow utility managers to detect leaks and view real-time information about water pressure and flow changes.

But if theft or leaks are detected and there is no political will to address theft or personnel to fix the leak, such technology is useless.

Instead, regional governments will need to focus as much on water governance as they do on increasing water supply. They will need to do so while carefully balancing powerful vested interests.

Reimagining the Fertile Crescent

Reducing agricultural demand for water in the birthplace of settled agriculture is a politically difficult but necessary place to start.

The Water Innovations Technologies (WIT) project in Jordan, which aimed to help households and farmers implement a number of water-saving activities, highlights why. It divided the cost of each activity by the volume of water saved to get a cost-effectiveness figure for each cubic meter of water. That number was nearly 170 times greater for agricultural investments than household ones. And the solutions implemented under the project were simple.

Agro-meteorological stations measure meteorological data such as temperature, rain, and air humidity.

Installing drip irrigation and sensors to determine precisely when the soil requires more water sounds complicated and expensive, but they are relatively low-tech and low-cost solutions.

Building on the success of the project, though, requires overcoming certain challenges that are common in many international aid projects.

Since Jordanian farmers’ water is still essentially free, farmers had little incentive to maintain these systems on their own after the end of the project. And since water consumption is poorly regulated, many farmers simply diverted the water they saved through the project to other uses. Overall water use stayed steady.

This program points to the limitations of projects that fail to address political challenges.

Farmers in most countries receive free water or pay a few cents per cubic meter for it. Illegal wells are also common.

Many reforms have rightly focused on raising prices, punishing water theft, and restricting water allotments. But powerful agricultural landowners make raising the cost of water or curbing theft difficult and sometimes deadly. In a wave of protests in Jordan in 2017, one slogan was explicit: “Raising prices is playing with fire.”

Sticks without incentives or alternatives for farmers are unlikely to work. Providing continuous support to farmers using water conservation systems is essential in the near term. Subsidizing less water-intensive crops may also be necessary to shift away from more water-intensive crops that have been grown for generations.

Hydroponics and vertical farming are also promising. They can use around 80-99 percent less water than open-field agriculture. If these energy-intensive practices can be powered by renewable energy, they could potentially be scaled. However, in many countries, excessive red tape tends to stymie these efforts.

Subsidizing, rather than frustrating these projects, would make them more financially viable, sustainable, and scalable with little political risk.

From Waste to Water

Reusing treated wastewater is another more politically feasible solution.

Treating wastewater and gray water protects freshwater supplies, increases water supply for uses that include agriculture and livestock fodder, improves health outcomes, and mitigates climate change. Reducing methane emissions through proper wastewater treatment can immediately reduce warming. Despite these benefits, many countries in the Middle East have little to no adequate wastewater treatment.

An outlier is Jordan. The As-Samra wastewater treatment facility in Jordan serves 65 percent of the country’s population. The large scale allows the plant to produce 80 percent of its own energy needs from biogas and hydropower. The treated wastewater is then routed to the King Abdullah Canal, adding over 100 million cubic meters of treated effluent to farmers’ limited water resources in the Jordan valley. While farmers were hesitant to use treated wastewater, simply adding the treated wastewater to existing agricultural water sources worked.

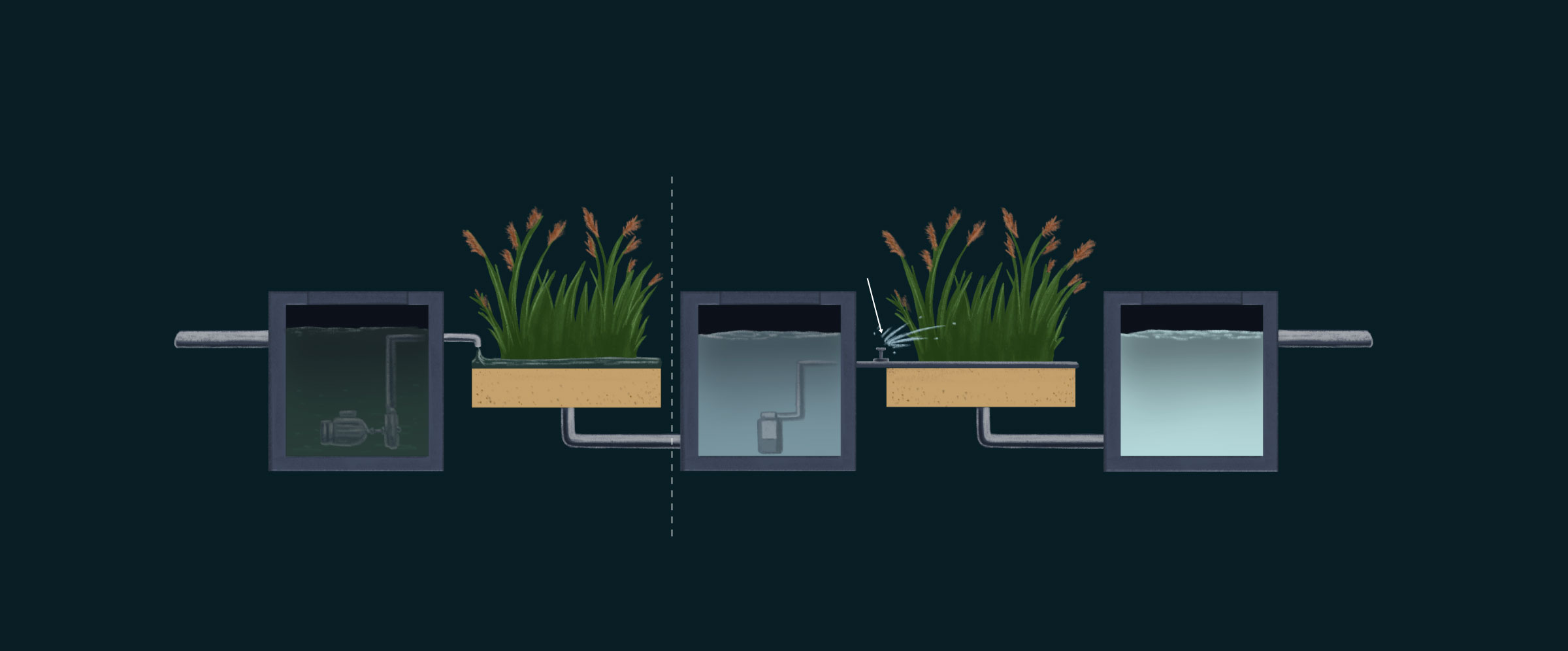

Some communities are also experimenting with decentralized wastewater treatment plants. Constructed wetlands can naturally treat wastewater. They have the added benefits of minimal energy, low maintenance, and little expertise needed.

Raw Wastewater Treatment By Constructed Wetlands

Improving the collection and treatment of gray water and stormwater would also reduce flooding hazards and increase supply.

Once again, the devil is in the politics.

While effective treatment is a game changer for water security, it is expensive. And many politicians are not willing to pay for the construction and maintenance of water-related infrastructure. In 2018, the Iraqi government allocated only $15 million, or less than 0.2 percent of the overall budget to the water ministry.

Wastewater treatment also arouses “not in my backyard” feelings. Often, residents think being close to a treatment plant will devalue their land or smell.

Raising the awareness of citizens on the risks of failing to treat wastewater will be necessary to put pressure on governments and convince communities of the benefits.

It's Not Just about Water

Urbanization

Addressing water insecurity will not just be about water. For much of the Middle East, the fallout of scarcity and climate change is irreversible and must be dealt with. Many farmers may abandon their farms for the cities for good, and the global trend toward urbanization is unlikely to slow. Failing to accommodate this urban growth could be disastrous.

Mohamed Bouazizi Square in Tunisia.

If farmers run out of water and move to cities where their livelihoods are criminalized, tensions will boil over.

This is what happened to Mohamed Bouazizi, a Tunisian man who set himself on fire in 2010 and the rest of the Arab world with him. Yet, his is a common story in the Middle East. As such, even water experts are now begging their governments to find job opportunities for citizens outside of agriculture.

On the other hand, if governments built up their cities more sustainably and inclusively, they could turn a seemingly harmful trend into one that adapts to climate change. Urbanization is an opportunity to move away from an agrarian economy—to which the most water-stressed region in the world is not well-suited—to other sectors.

Transboundary Relations

The aforementioned reforms will build trust not only between citizens and their governments but also with upstream neighbors. Improving water management within countries would make it more difficult for upstream countries like Turkey to blame downstream neighbors like Iraq for their own water woes.

However, improving transboundary water sharing will not just revolve around water. Developing other economic and political linkages with transboundary neighbors can also shift water from a zero-sum game to a more cooperative endeavor. Though Turkey and Iraq haggle over allocations of the Euphrates and Tigris Rivers, the countries’ important economic and political ties have, at times, pushed Ankara to release more water to its southern neighbor.

Building Trust to Move Forward

Both long-term planning and cooperation are needed for improving water security within and between states. But a low-trust environment, like the Middle East, shortens planning horizons and generates little incentives for cooperation.

Rebuilding that trust will require more transparency from governments and more awareness from citizens. A recent example comes from Jordan. In 2023, the government announced a gradual increase in water tariffs. Unlike previous price hikes, the resistance was moderate. Experts say it was due to a widespread public campaign to explain the reforms and the reasons for them.

Governments should view civil society as an ally in this process, rather than a threat. Activists, scientists, and academics can identify polluters and raise awareness among local communities on the need for change.

Conclusion

Water is the only resource in the Middle East that is vital to human life, increasingly scarce, and still cheap if not free. This is the recipe for a disaster that is already unfolding across the Middle East. Water shortages are sparking deadly protests, conflict, and displacement. Water security is quickly becoming a matter of national and international security.

Ignoring the political realities that brought the region to the brink is debilitating serious reform. Water reforms may have a technical foundation, but the implementation of reforms requires a political mindset to develop the right mixture of investments, incentives, and sticks for stakeholders in each context.

Time is running out. Governments, multilateral development institutions, and aid organizations must recognize that stability hinges on the provision of this most basic element of human existence.

No comments:

Post a Comment