Kamran Bokhari

A new generation of Iranian leaders is emerging that is ideologically far more hardline than what the country has produced since the founding of the Islamic Republic 45 years ago. Their rise is the result of the regime seeking to preserve itself in the face of a public increasingly disillusioned with an order long dominated by theocrats. The unprecedented scale of engineering in the country’s 2024 elections underscores an intensifying internal power struggle ahead of the succession of a new supreme leader. The Iranian political system cannot continue to suppress the public while also waging war against itself.

Ideologues vs. Pragmatists

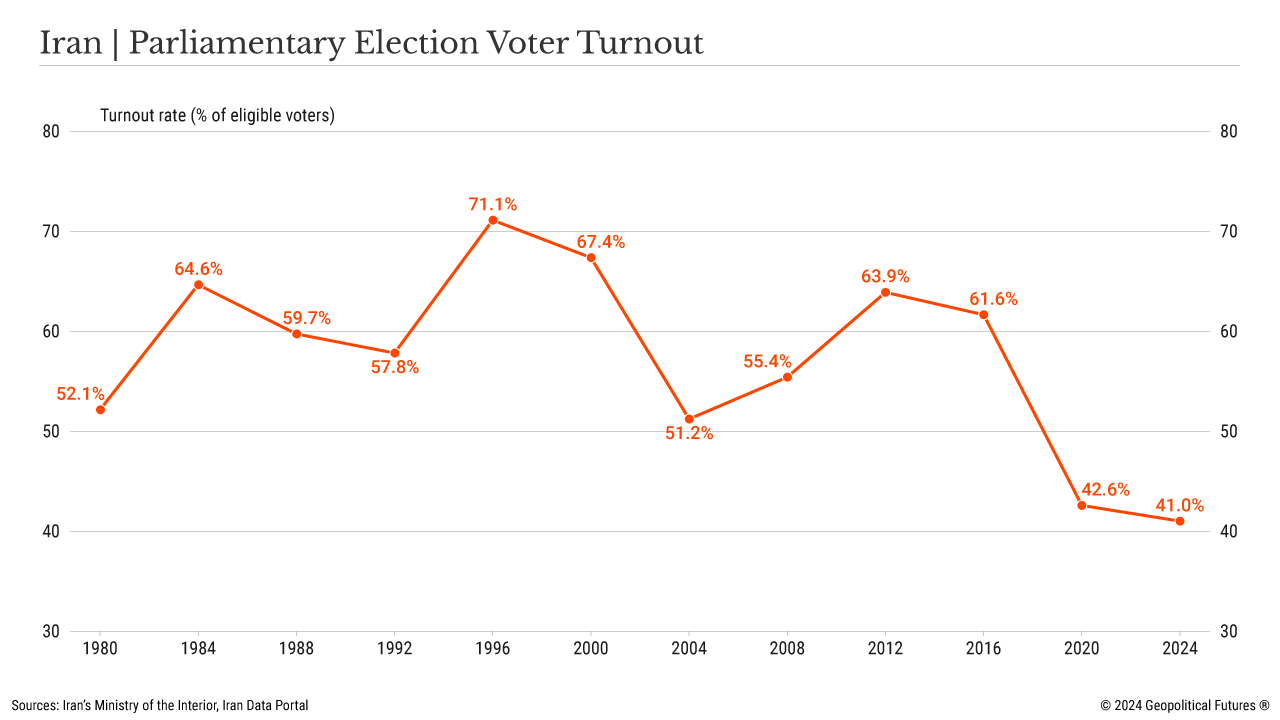

The 2024 parliamentary and Assembly of Experts elections held on March 1 saw the lowest turnout of any election since the founding of the regime in 1979. State media said a little more than 40 percent of the electorate cast ballots, while other reports suggested it was much lower. According to Middle East news platform Amwaj.media, the speaker of the outgoing parliament and a prominent former Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps commander, Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf, finished fourth in the race for seats in the capital, Tehran, where turnout was even lower at 25 percent. In the polls for the Assembly of Experts, the 88-member clerical body with the power to elect the supreme leader and remove him from office, the biggest upset was that Sadegh Larijani (who served as chief justice for a decade and hails from the powerful Larijani clan) lost his seat. That two-term former President Hassan Rouhani, who has been a top national security figure since the founding of the regime and held many key positions within its several elite institutions, was disqualified from running in the Assembly of Experts vote underscores the extent to which this year’s elections were manipulated.

Electoral engineering designed to give Iranian conservatives the upper hand dates back to the 2004 parliamentary elections. Ahead of that vote, the Guardian Council, a 12-member clerical body with the power to vet candidates for public office, announced the mass disqualification of reformists, a rising force since the 1990s. But rather than end the political infighting, the elimination of the reformists actually worsened it over the next 20 years, as competing conservative factions began to spar. During the presidencies of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and Rouhani, who each led Iran for two terms from 2005 to 2021, the struggle between pragmatists and ideologues was intense.

Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei has long arbitrated among the various factions jockeying for power and influence. However, in the past two decades, this process, which otherwise would largely play out behind the scenes, not only increasingly required his personal intervention but also became much more public. This was most visible during the Ahmedinejad era (2005-13) when the then-maverick president not only sparred with fellow conservatives in the establishment but also went on to defy Khamenei in his second term. Consequently, the fault lines in the conservative movement became much more acute, at a time when the U.S. was applying ever more sanctions pressure.

Khamenei’s solution was to enable the return of pragmatic conservative forces. In the 2013 elections, in which almost 73 percent of voters turned out, Rouhani soundly defeated his rivals. The move helped the supreme leader achieve two key objectives. First, it reestablished public support for the regime, which had been badly damaged by the controversial 2009 elections and subsequent months-long uprising led by the Green Movement. Second, it opened space for Tehran to negotiate a nuclear agreement with Washington amid the most severe sanctions that the country had experienced.

In addition to suffering serious financial pain from the sanctions, Tehran was struggling to balance an aggressive foreign policy agenda with the need for domestic calm. However, talks with the United States exacerbated rifts within the Iranian political establishment. While the Rouhani-led pragmatists viewed the talks as critical for national security, ideologues among the clerics and within the IRGC sought to limit contact with and concessions to the U.S. because they saw the negotiations as subversive to the regime.

The 2015 nuclear deal was a major victory for the pragmatists, but it was short-lived. The Trump administration’s 2018 decision to withdraw from the nuclear deal and reimpose sanctions seriously undermined Iran’s pragmatic conservatives. Iranian retaliation, including an attack in 2019 on a Saudi oil facility that disrupted half the kingdom’s crude production, led the U.S. to assassinate the head of the IRGC’s Quds Force, Qassem Soleimani, in early 2020. Soleimani’s killing galvanized the idealogues and further weakened the pragmatic conservatives, who had lost considerable ground during Rouhani’s second term (2017-21).

Not-So-Supreme Leader

In the lead-up to the 2021 presidential elections, the Guardian Council restricted the pool of candidates to ensure the victory of Ebrahim Raisi, a hardline ideologue and former prosecutor infamous for suppressing dissent in the country. But the pragmatic conservatives were not the only ones who were cut down to size; Khamenei’s own influence over the system had waned. This was evident when former national security chief and parliamentary speaker Ali Larijani, elder brother to former judiciary chief Sadegh Larijani and a favorite in the race, was disqualified. Khamenei tried to have the decision reversed, but the Guardian Council stood its ground.

Beset by speculation about his advanced age and failing health, Khamenei had long been losing influence as the system he fashioned and presided over for more than 30 years prepared for his successor. Meanwhile, the IRGC-led security establishment was gaining strength. The hardliners feared that they could be sidelined, especially with the armed forces not being as committed to theocracy as the clerics are. But in Raisi they had one of their own as president.

Raisi’s administration is the most right-wing in the history of the Islamic Republic. In an attempt to solidify its hold over the state, especially in the wake of several rounds of protests in recent years over increasingly harsh economic conditions, the Raisi government tightened public restrictions, especially the public dress code for women. This led to the September 2022 death of Mahsa Amini, a young woman from Kurdistan province, while in the custody of the morality police. Amini had been arrested for not properly wearing the hijab while she was visiting the capital. Her death sparked the worst public protests since those that brought the Islamic regime to power decades ago. Protesters across the country, many of whom were women, openly defied the authorities in violent demonstrations that lasted nearly a year.

Such was the level of unrest that many senior regime figures criticized the government and warned that the agitation threatened the Islamic Republic. Khamenei himself was forced to go on the defensive and issued a public statement that women who do not conservatively abide by the hijab should not be seen as less loyal citizens. Top regime figures announced that the laws related to the female public dress code would be revised, though no concrete actions have been taken. The demonstrations died down by mid-2023, but they were akin to a systemic shock to the regime, which feared that mass protests threatened its existence ahead of a critical transition. Divisions within the regime became even more acute.

In an effort to preserve their influence, the ideologues sought in this month’s elections to obtain a majority in the parliament and, more important, in the Assembly of Experts. Given that the Assembly of Experts is elected for an eight-year term, its new members will most likely decide who succeeds Khamenei to become the country’s third supreme leader. Meanwhile, the ideologues’ hold over the Guardian Council enabled them to eliminate competition from the pragmatists. Nevertheless, many districts are due to hold runoffs to fill parliamentary seats, while the precise composition of the Assembly of Experts remains unknown.

Between widespread and growing public disaffection, worsening economic conditions and intensifying power struggles among elites, the Iranian regime’s future will likely be decided by the country’s armed forces, which are not immune from broader public sentiments.

No comments:

Post a Comment