ANUPAM MANUR

Barely a few days into summer and there are already reports of Bangalore facing a severe water crisis. Groundwater is depleting and borewells are running dry. The price charged by private tankers have doubled. Some apartment complexes and RWAs are already rationing water and cutting off water supply to households for a few hours in the daytime. Meanwhile, the state government has decided to nationalise all private water tankers in the city.

This is a complex problem with multiple causal factors – geography (Bangalore is situated far away from any naturally occurring water body), weather (weak southwest monsoons), and mismanagement. Mismanagement takes the shape of encroachment and building property on lake beds, failure to enforce rainwater harvesting systems, not providing piped water supply to peripheral areas, and unabated exploitation of ground water.

Grossly Underpriced

In the discourse on Bangalore’s water crisis, while many causes and potential solutions are strewn about, pricing of water does not attract attention. At the heart of it, the water crisis is a demand and supply problem. There is excess demand and less supply and unfortunately, water is criminally underpriced in our cities.

Water maybe a free gift of nature, but that is only if you live near the water source. For most of us living in dense urban areas, it taken an enormous amount of resources to deliver water from the source to the taps in our homes. Thus, potable drinking water is an economic good, which comes at a cost.

For Bengaluru homes, Cauvery water is pumped all the way from TK Halli, approximately 150 kms away with elevation changes of about 300-400 metres. The Bangalore Water Supply and Sewerage Board (BWSSB) collects, pumps, treats, and stores water in its many reservoirs, and distributes it through the network of pipes across the city. Add electricity, staff and maintenance costs to the mix and it is estimated that BWSSB spends roughly Rs 80-100 per kilolitre supplied.

What do we pay for this?

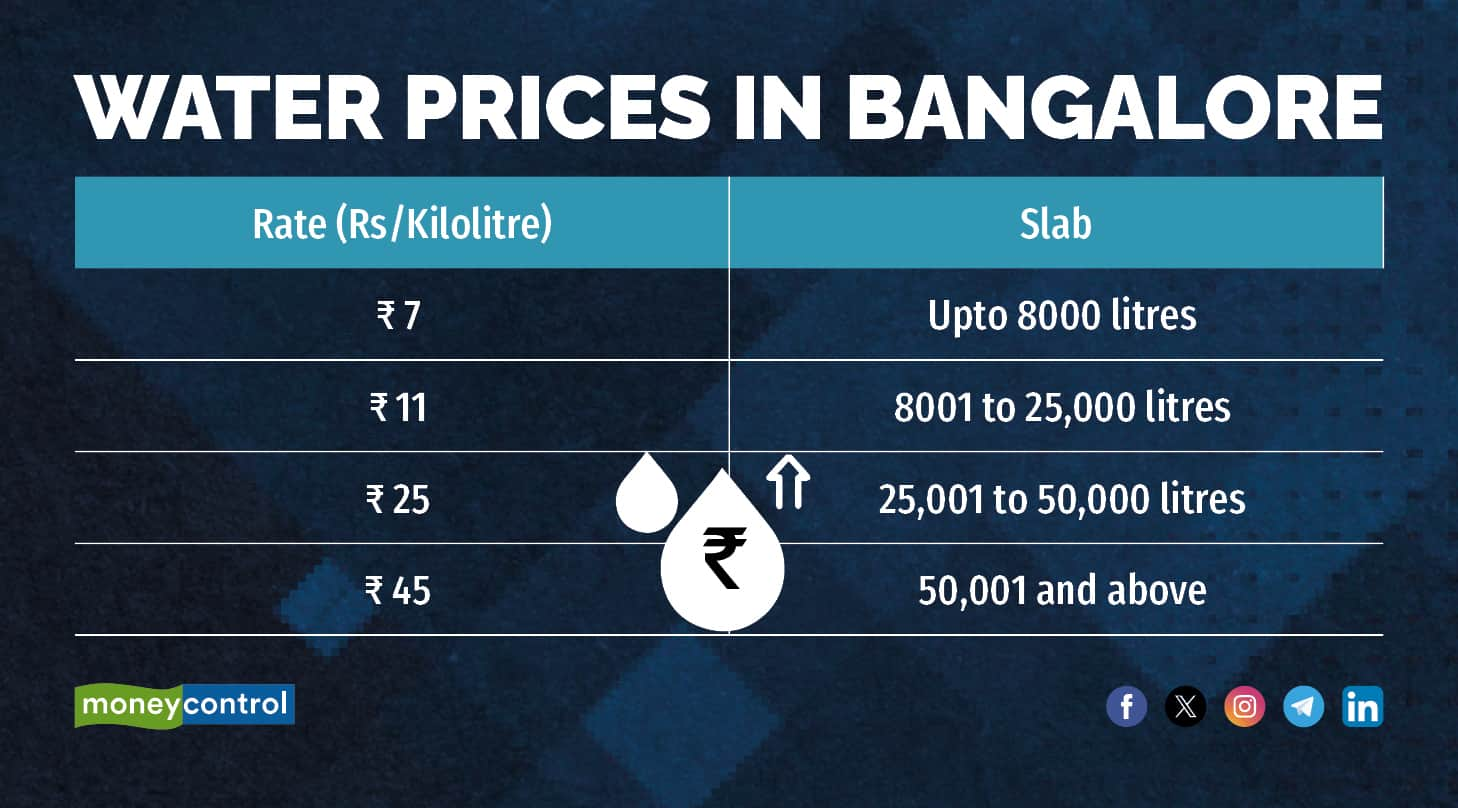

An average urban consumer uses about 130 litres per day. A household of 4 consumes 520 litres per day and about 15,600 litres a month. While they pay Rs 172 as the monthly bill, the cost to BWSSB is Rs 1248 - 1560.

Mispricing is Anti-Poor

The difference between the cost of supplying and the price charged is made up through public funds. Every single litre of water consumed is subsidised through taxpayer money. Since there is a per litre subsidy, the higher the water consumption, the greater the subsidy from the government. It should also be apparent that the rich consume more water than the poor. The poor might consume water for activities such as drinking, cooking, and bathing, the rich will use water for watering their lawns and cleaning their cars. The aforementioned household consuming 15,600 litres gets a subsidy of roughly Rs 12,912 – 16,656 per year. Since taxes are paid by everybody, this is a bizarre redistribution of resources to the rich.

Further, due to the gross underpricing of water, the main water agency is perennially broke and in debt. Though municipal finance in general and the BWSSB’s account books in particular are notoriously opaque, there are estimations that the annual revenue shortfall runs into hundreds of crores. A cash-strapped water agency has serious consequences for the city:

1. Leakages: The lack of funds and accountability reflects in poor maintenance of pipes. Out of nearly 1350 million litres of water sent from TK Halli, only about 840 million litres reach the target destination. That’s 38 percent wastage. In 2021, it took BWSSB 6 months to repair a leak in the main pipelines, by which time, nearly 1 million litres per day was wasted (180m total). Let that number sink in.

2. Theft and appropriation: There are thousands of illegal connections in the city and other forms of theft of water due to the inability to keep track of metred connections. Worse, BWSSB has no capacity or resources to track the usage and extraction of underground water. Many tankers extract underground water and sell it at a premium.

3. Water contamination: Improper treatment of water leads to contaminated water. There have been many instances when residents have received sewage water in their water pipes. This also disproportionately affects the poor as the rich are able to afford RO water purifiers to the glee of Hema Malini.

4. Unreliable and partial supply of water: The BWSSB provides piped water to the core of the city, while the periphery gets short-changed. While some of this periphery is high-end tech corridors, other parts of it are rural areas gobbled up by Bangalore city. While the rich can afford to call in tankers, the poor cannot afford it. Most slums which do not have piped water connection end up paying Rs 2-4 for a pot of water, which translates to Rs 200/kilolitre, far more than what the highest slab is for piped connection.

Ensuring that the water supplier has resources and having a strong governance and accountability framework can solve most of the above problems.

Incentives for Conservation

Unfortunately, most solutions are confined to awareness campaigns and requesting people to conserve water, which will have a negligible impact. Change can occur when incentives are aligned with conservation effects. If we want people to fix a leaky tap, close the tap while washing or shaving, and generally conserve water, it must pinch their wallets. At the margin, people will respond to the higher price. By pricing water so low, we are also sending out a signal that water is found in abundance and that there is no shortage, which is clearly counter-productive.

Even laws which have mandated rain-water harvesting has been largely ineffective (only 2 lakh household have this system set-up). Strong laws but with no state capacity to enforce and no incentives for compliance usually do not work. To note, all of this is confined only to urban water shortage, which pales in comparison to the mess of agricultural water supply strategy.

Keeping water prices low for the sake of the poor is clearly harming them. Instead, charge water at the highest marginal rate of supply. Use the additional resources to give targeted subsidies to only those who need it, as against everybody in the city. This can be done through vouchers or direct benefit transfers. Water is indeed a gift of nature; it is time we value it correctly!

No comments:

Post a Comment