Rich Outzen

Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has sought to be the world’s leading geopolitical balancer. So why is Turkey’s president so off-balance in the Gaza conflict?

The answer requires an understanding of the Turkish balancing act, which predates Erdoğan by decades—perhaps centuries. That act stems in part from the country’s central geographical position as a mid-sized power between Europe and the Middle East, Africa, and Eurasia, which necessitates and rewards flexibility toward all neighbors as threats and opportunities shift. It also stems from Turkish strategic culture, which has prioritized over many generations the pursuit of leverage in crises, peace deals, trade arrangements, and other geopolitical outcomes through patient, pragmatic, and often quite variable negotiating positions. To the frustration of great powers and neighbors who might prefer a more pliant and predictable approach, no one plays the balance and leverage game quite like the Turks.

And Erdoğan has become an adroit practitioner of this act. After idealistic (“zero problems with neighbors”) and unilateralist (“precious loneliness”) phases in his approach to foreign policy, he has over the past decade developed a mastery of balancing and realpolitik in a series of crises from Afghanistan to Ukraine. Erdoğan has returned a nation located figuratively at the center of the world to the center of global diplomatic activity and intrigue.

But the struggle between Israel and the Palestinians has defied this aspiration of leverage through balance. During the current war in Gaza, as during the 2008-2009 Gaza crisis, Erdoğan has abandoned careful rhetoric and engagement with both sides of the conflict and instead chosen to throw his weight overwhelmingly behind one side—in this case, that of the Palestinians.

The open question now is whether Erdoğan—and Turkey itself—can regain geopolitical balance. Tightrope walkers who fall don’t always have a net.

Ukraine, the model case

Ukraine's President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, left, visits Istanbul. Erdoğan has been careful to maintain economic and diplomatic ties with Moscow during the war in Ukraine.

Russia’s war on Ukraine provides the clearest example of Erdoğan's pattern of balancing in Turkish statecraft. On one hand, Ankara has made serious and substantive commitments to Ukrainian sovereignty. These have included legal and rhetorical steps such as not recognizing Russia’s annexation of Crimea and criticizing the Russian invasions in 2014 and 2022. They have also included robust military support and provision of lethal aid—well before Western powers were willing to provide such aid.

On the other hand, Erdoğan has been careful to maintain economic and diplomatic ties with Moscow during the war in Ukraine. Ankara has supported United Nations (UN) General Assembly condemnation of Russia but not broad and deep US and European Union sanctions. Erdoğan has opposed Western efforts to diplomatically isolate Russian President Vladimir Putin, continuing to engage him on a variety of issues. Bilateral Turkish-Russian trade has increased since Russia’s full-scale invasion.

Turkish diplomatic efforts to broker an end to Russia’s war in Ukraine, reflecting Ankara’s unique position as the only power that has retained relations of trust with both sides, have yet to yield conclusive results. Erdoğan has succeeded in negotiating more limited arrangements between the two sides, including several rounds of prisoner swaps and a grain-export deal that eased global cereal prices and helped Ukrainian farmers during the year or so that it was in force, though he failed in attempts to achieve an extension or follow-on grain deal. Overall the Turkish approach can be described as a sort of “pro-Ukrainian neutrality” that has protected Turkish economic and political interests and helped maintain a rough military balance that avoids Ukrainian collapse. This strategy has preserved the potential for Turkey to take a leading role in negotiating a peace agreement and reconstruction processes when the war eventually ends. Case in point: Erdoğan will host Putin for a visit this month to discuss the war, in the Russian president’s first visit to a NATO country in four years.

Another dimension of Turkish balancing has played out on the margins of the war in Ukraine: Sweden’s application for NATO accession. Turkish concerns over Stockholm’s laxity regarding recruiting, fundraising, and propaganda activities carried out within Sweden by the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), an anti-Turkey movement recognized as a terrorist organization by the United States and European Union, led to a nine-month delay in ratification by the Turkish parliament. Ankara used its veto right over NATO enlargement to obtain greater enforcement of anti-PKK laws in Sweden, while the United States has used Turkey’s interest in purchasing F-16 fighter aircraft as leverage to press Turkey to approve Sweden’s entry. Ankara defied nearly a year of mounting pressure from Western allies to ratify in order to highlight and achieve progress on counter-terrorism and arms sales—balancing in this case between multilateral and national priorities for leverage, rather than among competing geopolitical players. On January 25, Erdoğan signed the accession approval after his parliament ratified it, following a reported agreement for US President Joe Biden to champion the F-16 deal. On January 26, the State Department officially notified Congress of its intent to sell F-16s to Turkey.

From the Middle East to Latin America

A Syrian woman walks past Turkish Red Crescent tents at Reyhanli refugee camp on the Turkish-Syrian border in 2012. Turkey has sheltered millions of Syrian refugees.

The most consequential Turkish balancing maneuver may be playing out in Ukraine, but there are many other examples. The war in Afghanistan stands out as the longest-run case, with roughly twenty years between the initiation of Turkish logistical and combat support to the NATO mission in Afghanistan and the departure of Turkish troops after the fall of Kabul to the Taliban in 2021.

Yet throughout the twenty years of military backing to NATO’s International Security Assistance Force, Turkish troops carefully avoided engaging the Taliban in direct combat, and the Turkish government maintained—and facilitated for the United States—discreet contacts with Taliban leadership. Turkey is the only NATO country to retain a diplomatic presence in Afghanistan after the Taliban’s 2021 takeover. Ankara has refrained from formally recognizing the Taliban government, but has allowed Taliban representatives to operate Afghan diplomatic facilities on Turkish soil. Erdoğan seems to view Turkish involvement in Afghanistan as a boon to his bona fides as a humanitarian leader and leader within the community of Muslim nations. Continuing outreach and aid to struggling communities despite their government’s international isolation is a form of “humanitarian diplomacy” the Turks have carried out in Afghanistan, as well as in many countries in Africa.

Syria presents another complex example. The Turkish approach has evolved from demanding that Syrian dictator Bashar al-Assad must go between 2011 and 2016 to demanding that the PKK must go, beginning in 2016. Ankara fought against Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS) forces (both through the multinational anti-ISIS coalition and unilaterally), sheltered millions of refugees, and supported the international isolation of Damascus. Yet the Turks have also consulted and coordinated with Assad-backers Iran and Russia through the trilateral Astana format to manage tensions stemming from the conflict. And they have pursued their security interests through unilateral military operations in the country despite US objections. By maintaining cooperation with the West on certain issues and the Russians and Iranians on others—even as Turkish forces have confronted Iran and Russia or their proxies militarily—the Turks have exercised a sort of veto on any resolution of the conflict that would leave the PKK in control of Syria’s border with Turkey via its Syrian branch, known as the People’s Defense Units or YPG. The Turkish “safe zone” in northern Syria may be incomplete and not very safe, but it confers on Turkey leverage that will be key to shaping post-conflict conditions in Syria.

Turkey’s role in the geopolitics of the Gulf countries has also reflected a complex balancing game. The centerpiece is Ankara’s steadfast mutual commitment with Doha, including massive Qatari investment in the Turkish economy, bilateral military cooperation, and wide-ranging diplomatic collaboration between the two governments. Most critically, the Erdoğan government responded in 2017 to threats by Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), supported by other Arab countries, to isolate and potentially overthrow the Qatari government by extending robust military and diplomatic support to Qatar. Turkey deployed military forces to deter an external attack against its ally, and the two countries agreed that Turkish forces would maintain a brigade-sized base on the outskirts of Doha. Yet the firm Turkish-Qatari arrangement has not prevented Erdoğan from pursuing rapprochements with Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and other regional actors since 2020 as part of a diplomatic “charm offensive.” Both Turkey and Qatar have maintained cordial relations with Iran while opposing Tehran’s hegemonic ambitions in the Gulf.

In Libya, the tightrope has run between supporting and empowering Western diplomacy and vigorously pursuing Turkey’s national interests. The former was aimed at achieving a political bargain among warring Libyan factions in the decade after the death of Libyan dictator Muammar Qaddafi. The latter involved launching a direct military intervention on behalf of the UN-recognized Government of National Accord (GNA) to prevent its removal from Tripoli by the forces of Khalifa Haftar, a Tobruk-based former Libyan military officer seeking to be the country’s new strongman. The price of that intervention? A long-term Turkish military training and assistance mission in Libya, as well as a maritime demarcation agreement that favored Turkish territorial claims in the Mediterranean.

The inability of Tobruk and Tripoli to reconcile had led many in the West to tacitly condone an offensive by Haftar’s forces against the national capital. Based on 2019-2020 atrocities committed by Haftar forces in Tarhuna, east of Tripoli, there is a high likelihood that a Haftar victory would have been a humanitarian catastrophe. Ankara signed several military agreements with the GNA, then proceeded to rout Haftar’s forces, including Russian Wagner Group mercenaries. The campaign not only spared Tripoli, but also stabilized battle lines between eastern and western Libyan forces in a manner that re-energized UN-led diplomatic efforts. Turkey also supported post-war efforts to bridge the gap between the Libyan factions. A ceasefire among armed factions continues to hold, likely due to a tacit agreement between Russia and Turkey (backers of the respective sides in the 2020 fighting), and while national unity talks have progressed little, a return to large-scale violence does not appear imminent.

Turkey has also been quite active elsewhere in Africa. Over the last two decades, Turkey has dramatically expanded its trade volume and diplomatic relationships across the African continent, more than tripling diplomatic outposts and sextupling trade. Rather than focusing on a small number of anchor partners, Ankara has sought to develop broad-based ties with a diverse network of countries. The Turkish approach has also had a military component. One recurring theme has been avoidance of bloc or alliance behavior; Turkey has sought to establish numerous relationships of bilateral benefit without an organizing logic rooted in choosing sides. In brief, Turkey has pursued “unwavering pragmatism” to further its regional interests. Put more assertively, Turkey has cast itself as an African power.

Turkey’s involvement in Latin America was relatively stagnant prior to 2015 but has been more active since. Primarily in the interest of expanding trade, Erdoğan has deepened relations with Cuba and Venezuela. But it’s not just those two; Ankara has pursued a balanced approach to trade—and diplomacy—across the region, regardless of the partner government’s ideological leanings, resulting in broader regional engagement without excluding or marginalizing particular countries. Erdoğan’s opening to Latin America has been motivated largely by trade, but also by a desire to enlist mid-sized powers in the region to dent the perceived arbitrary clout of the United States and European states in international institutions. Erdoğan’s popularized this move in Turkey with his slogan “dünya beşten büyüktür” (“the world is bigger than five”), meaning the UN Security Council’s permanent membership should be expanded beyond five countries.

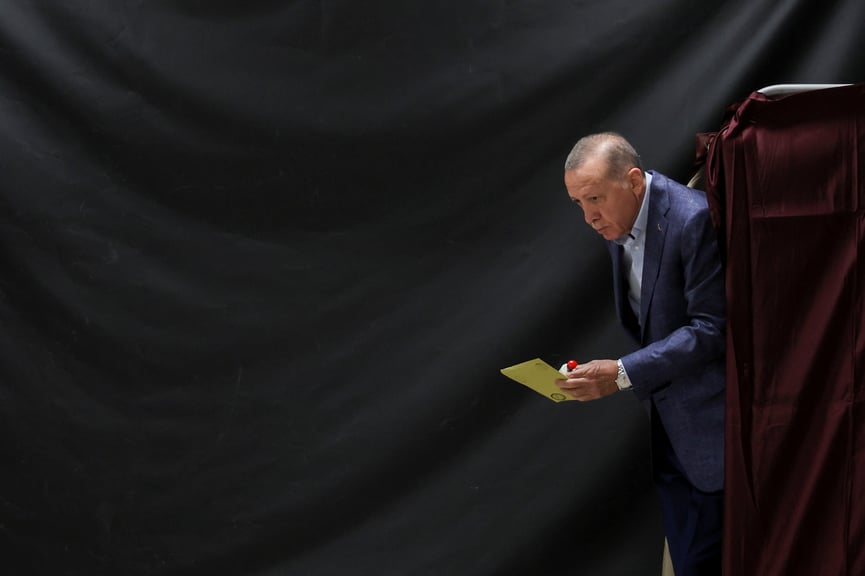

Losing his balance

Erdoğan walks out of a voting booth at a polling station in Istanbul in May 2023.

In some exceptional but notable cases, however, Erdoğan’s Turkey has not applied a balancing policy. One clear example is the dispute between India and Pakistan. Turkey has long been a steadfast partner of Pakistan and has shown no interest in cozying up to India as a hedge against China along the lines the United States has. As a consequence, ties between India and Turkey are more strained now than at any previous point in recent memory. Erdoğan has drawn parallels between the Pakistani stance on Kashmir and the Turkish defense against British imperial forces at Gallipoli during World War I. Turkey has also eschewed a balancing strategy in the Caucasus, unequivocally backing Azerbaijan in its efforts to regain control of territories seized by Armenia in the early 1990s, including crucial arms and advisory support during Baku’s 2020 military campaign and 2023 retaking of Nagorno-Karabakh.

In the case of the Palestinians, Ankara first pursued, but ultimately abandoned, a balanced position. Turkey was the first majority-Muslim country to recognize Israeli statehood, and preserved cordial relations with Israel throughout the years of Arab-Israeli wars in 1956, 1967, 1973, and 1982. The 1990s were a “golden age” for security and political coordination between the United States, Turkey, and Israel—a dynamic seen in the West as a stabilizing factor in the Middle East and eastern Mediterranean. During the first decade of Justice and Development Party (Adalet ve Kalkinma Parti, or AKP) rule starting in 2002, Turkey maintained positive relations with Israel despite harsh criticisms of Israeli treatment of Palestinians during the Second Intifada in the early 2000s. Then-Prime Minister Erdoğan visited Israel in 2005, and as late as 2008 Ankara served as a mediator for exploratory peace talks between Syria and Israel. Turkish policy continues to balance engagement between the more moderate Palestinian Authority, inclined to cooperate with Israel, and the more militant Hamas.

Yet Erdoğan, more than previous Turkish presidents or prime ministers, has evinced a visceral and personal concern for the Palestinian cause—one with religious, historical, and civilizational overtones that has made it difficult to sustain a balanced position. Since 2009, these factors have rendered the Turkish balancing act impossible.

Three times since 2009, Israeli military operations against Gaza-based Hamas militants—or, more precisely, civilian suffering and collateral damage caused by those operations—have prompted Erdoğan to issue extended and bitter criticisms of Israel. These outbursts played well at home but undermined prospects for Turkey to play a mediating or a stabilizing role between Israel and the Palestinians. The first came after Operation Cast Lead in 2009, when Erdoğan confronted then-Israeli President Shimon Peres at the World Economic Forum in Davos. The second came with 2014’s Operation Protective Edge, during which Erdoğan compared the Israeli offensive to the atrocities of Adolf Hitler. The most recent Israeli operation, launched after the deadly Hamas terrorist attacks of October 7, has produced even more pointed rhetoric from Erdoğan, who has called for Israel to be prosecuted for war crimes and cast Israel as “a terrorist state” seeking to wipe out the Palestinian population altogether. Debunked reports that Erdoğan threatened military intervention in Gaza notwithstanding, his fiery anti-Israel speeches and statements comport entirely with his rhetorical pattern during previous Gaza wars

Erdoğan’s lack of balance on Gaza and the Palestinians stems in part from domestic politics, including pressure from Islamist and anti-Western elements of his political coalition to push back on the West—in this case, US-backed Israel. Yet the majority of the Turkish public supports a mediating or neutral role for Turkey in the Israel-Hamas conflict, so there is no political profit from pushing the envelope so far that Turkey is no longer a credible mediator. Erdoğan may also be motivated by a desire to burnish his credentials as a leader of the Muslim world and protector of the oppressed in his region—narratives in which the Palestinian cause has played a central and recurring role. It’s not as if Erdoğan is the first Turkish leader to publicly accuse Israel of genocide and atrocities against the Palestinians; his predecessor as prime minister, Bulent Ecevit, did just that regarding the policies of then-Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon in 2002. What’s most remarkable about Erdoğan is his willingness not only to go against his own brand by abandoning a balanced position on multiple occasions over the same issue, but also to undo the painstaking work of his own foreign-policy team to pursue a reconciliation with Israel over the past several years. It seems fair to conclude that Erdoğan has struggled with a personal attachment to the Palestinian cause that extends beyond his other foreign-policy proclivities, since he has demonstrated far more agility on the latter than on the former.

During the first two weeks of the present crisis, Erdoğan maintained a degree of constructive neutrality. He made offers to mediate and commit his country to a security “guarantor” role, and strove to maintain open communications with both sides. After reading reports of a reputed Israeli bombing of the Al-Ahli hospital in Gaza, which were later refuted, Erdoğan’s tone became less measured and more visceral. Meanwhile, such negotiations as have taken place have been mediated by Egypt and Qatar. Both of these countries have closer ties with Hamas now that Turkey has sent Hamas leadership packing—which Ankara did earlier in the conflict when it was more balanced—and both Egypt and Qatar have been more discreet in their public statements about the conflict. Erdoğan’s rhetorical excesses have lowered confidence among Israeli and US policy elites that Turkey is even-handed enough to mediate the conflict, as it has in other conflict zones, or to play a key role in stabilizing Gaza post-conflict, despite Turkey possessing the contacts, resources, operational capabilities, and will to do so.

Anomaly, error, or norm?

A person walks behind a flag with an image of Erdoğan ahead of the presidential and parliamentary election in Istanbul in May 2023.

Turkey’s one-sided policy response and unrestrained rhetoric regarding the current Gaza conflict have exacted costs, keeping Ankara on the sidelines—including in negotiations over hostages and ceasefires—and halting a reconciliation with Israel that could pay economic dividends for Turkey. For Erdoğan, there have also been some offsetting domestic political benefits, because the Palestinian cause is a popular one among the Turkish public at present. Whether the unbalanced positioning ends up being a serious misstep in Turkish statecraft or a less significant anomaly depends upon how the conflict ends and how Gaza is stabilized.

Even if Erdoğan’s stance on Gaza is more than just an anomaly, it is certainly less than a paradigmatic shift. Especially as a president in the first year of what may well be his final term, he is unlikely to gamble his legacy of balanced strategic positioning across multiple regions that has allowed him to advance Turkey’s strategic interests, from counterterrorism to energy access. Erdoğan’s positioning on the Gaza conflict is best thought of as a serious and recurring, though peripheral, shift in his balancing portfolio.

A return to a more balanced and pragmatic Turkish position on the conflict between Israel and the Palestinians, moreover, is certainly conceivable, and may be precisely what Erdoğan intends to do after deploying harsh rhetoric to signal solidarity with the oppressed in Gaza to his multiple audiences at home and abroad. Observers have noted that Ankara continues to support back-channel diplomacy through Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan and intelligence channels to prevent regional escalation and limit the fallout of the war. Despite public demonstrations of sympathy for the Palestinians among segments of the Turkish public, expect Ankara to gradually lower the temperature and seek ways to be part of de-escalation and relief efforts in Gaza. Meanwhile Turkish-Israeli bilateral trade is still booming, with new deals being signed even as the war in Gaza continues. The painstakingly constructed reconciliation highlighted by the September meeting between Erdoğan and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu in New York has been effectively put into deep freeze, but a degree of security and economic cooperation continues. The fact remains that Turkey under Erdoğan, while a difficult ally for the West, is nevertheless geopolitically potent, inclined to balance as a norm, and better to have as a partner than an adversary, which means positive roles for Turkey in relief, reconstruction, and stabilization efforts related to the conflict remain possible.

There is a Turkish proverb that nicely sums up the Turkish balancing act as applied across the Middle East, the Balkans, and the Black Sea: zor oyunu bozar (“force can undo a game of trickery”). Variations on this proverb became quite popular in the Turkish press just before and after the Libyan military campaign: oyun kuran, oyunlari bozan bir Türkiye var (“now there is a Turkey that sets and upsets the games”), and oyun oynanan değil, bölgesinde oyun kuran, oyun bozan kararlı bir Türkiye var (“no longer the table where games are played, now Turkey is the player that sets and upsets the game”). The proverb as applied to most regional conflicts retflects a more self-aware, agile, and confident Turkish approach—one that has strengthened Ankara’s ability to influence geopolitical outcomes in which Turkey has a vital interest. Diplomacy, military strength, and economic ties have all played a role in such balancing arrangements.

No comments:

Post a Comment