Igor Delanoë

Introduction

There is no end in sight for the fighting in Ukraine, but some lessons can be already drawn out about the naval side of the conflict. Although the “special military operation” remains essentially a ground conflict, with limited involvement of the air forces, developments at sea have taken place in the Black Sea from the very beginning of the hostilities. As one of the leading naval formations in the Black Sea basin, Russia’s Black Sea Fleet (BSF)—one of Russia’s five naval components[1]—has been involved in the operations. This paper examines the evolving role of Russia’s BSF throughout the conflict.

Whereas Russia’s BSF had a theoretical superiority over the Ukrainian maritime forces when the conflict broke out, it has been unable to exploit this advantage and found itself in a partly defensive posture within a few months. This shift in the BSF’s posture is inherently tied to the balance of power on the front and the evolution over time of the fighting toward an attritional conflict. The analysis of the developments at sea since the beginning of Moscow’s campaign in Ukraine shows that the scope of the missions fulfilled by Russian naval forces in the Black Sea has increased over the past twenty months and that the BSF plays a greater role today than it did at the early stage of the “special military operation.” Although it has adapted to new challenges posed by Ukrainian operations against Russian civil and military naval infrastructures in the Black Sea, the BSF has not been able to overcome all the difficulties emanating from an asymmetric warfare at sea caused by the Ukrainians’ employment of naval drones and cruise missiles. [2]

As the fighting continues, it should be kept in mind for methodological purposes that many uncertainties remain regarding how this conflict will evolve and eventually end. Its outcome—and the scale of Ukraine’s potential territorial concessions—will influence Russia’s posture in the Black Sea basin for decades. Nevertheless, building on this provisional assessment, some possible solutions Russia may consider to enhance its strategic position in the Black Sea region can already be envisaged. Finally, it has been increasingly difficult for experts to work with Russian open sources dealing with Russian armed forces in general, and with the BSF in particular, due to new laws adopted to protect information relating to defense issues.[3]

Russian Navy’s ship is seen during the joint drills of the Northern and Black Sea fleets, attended by Russian President Vladimir Putin, in the Black Sea, off the coast of Crimea January 9, 2020.

The Black Sea Fleet meets the “special military operation:” Contested Supremacy over the Ukrainian Maritime Forces

Being responsible for an area spanning from the Black Sea to the Atlantic Ocean, with sporadic deployments as far as the Indian Ocean, the BSF has been modernized under the auspices of the 2011–2020 State Defense Plan.[4] During the 2010s and up to February 24, 2022, the BSF received three frigates (Project 11356, type Grigorovich), six small conventional attack submarines (Project 0636.3), and four small missile corvettes (Project 21631), all capable of delivering Kalibr long-range cruise missiles. These new units have consolidated the status of the BSF as a local dominant naval power as other Black Sea navies (Ukrainian, Georgian, Bulgarian, and Romanian, with the exclusion of the Turkish navy) do not have the same capabilities as Russia’s BSF.[5] Theoretically, the aggregated firepower of these vessels would allow the BSF to deliver a salvo of ninety-two cumulated Kalibr cruise missiles, which is, for comparison, as much as one Arleigh Burke-type US Navy destroyer. However, until the conflict in Ukraine, part of these units was regularly dispatched beyond the Black Sea for patrol missions mainly in the Eastern Mediterranean. The BSF also received a batch of four patrol boats (Project 22160), three minesweepers (Project 12700), one intelligence vessel (Project 18280), and a few support vessels. On the eve of the “special military operation,” the BSF was therefore probably the most refreshed and powerful Russian naval formation among those—the Baltic Fleet and the Caspian Sea Flotilla—not fulfilling strategic nuclear deterrence missions, like the Northern and Pacific Fleets.

Up until February 24, 2022, the BSF fulfilled so-called sovereignty missions (protecting Russia’s territorial waters, offshore installations, etc.) and tracked NATO surface units when they appeared in the Black Sea basin. Since the conflict broke out, the BSF’s core mission has been to enforce Russia’s naval supremacy in the Black Sea basin. To fulfill this mission, the BSF depends on the firepower of its own units and also on the various defense systems deployed in Crimea, such as the S-300 and S-400 anti-air systems, Bastion coastal batteries, and Bal anti-surface missiles. Likewise, electronic warfare (EW) assets and air assets dispatched in Crimea, in the Krasnodarsky krai, and the Rostov region complement BSF capabilities. All combined, these elements create a so-called bubble or an A2/AD complex, making operationally more difficult—but not impossible—and more costly any attempt by a hostile force to penetrate the area. Russia was also well aware that, in the case of an armed conflict breaking out in the Black Sea region, Turkey would quasi-automatically invoke the provisions of the 1936 Montreux Convention (Articles 20 and 21 more specifically), which legally allow Ankara to close the Turkish Straits (the Bosporus and Dardanelles) to all military vessels for a period of time at its discretion.[6] In other words, Moscow’s basic assumption was that, in case of a military crisis in the Black Sea region involving Russian interests or perceived as such, it would have free hands on the Black Sea naval stage to carry out whatever objectives it may assign to the BSF.

Beyond the Black Sea theater, the BSF was tasked with patrolling the Mediterranean, with a focus on the Eastern Mediterranean where the Russian Navy can count on a relatively favorable logistical environment and an air-sea complex, thanks to Russia’s presence in Syria. The Russian Mediterranean Squadron has been deployed in the Mediterranean permanently since 2010 (but formally reinstated in summer 2013) and is assigned under the command of the BSF, which also has provided the bulk of the platforms. However, this squadron has been regularly reinforced with units coming from Russia’s other naval formations on a rotating basis. Through the deployment of Kalibr capable vessels and diesel electric attack submarines in the Mediterranean, the BSF has been also fulfilling a nonnuclear strategic deterrence mission, as stated in the Russian military doctrine.[7] Russia’s military installations and armament systems in the Black Sea and the Eastern Mediterranean—the bubble—and Kalibr-equipped BSF units’ deployment across the wider Black Sea region are part of the Russian southern strategic bastion. This bastion has been aimed at protecting Russia’s southern flank from perceived dangers and threats, including the perceived Euro-Atlantic expansion of influence and the installation of US missile defense sites in Romania.

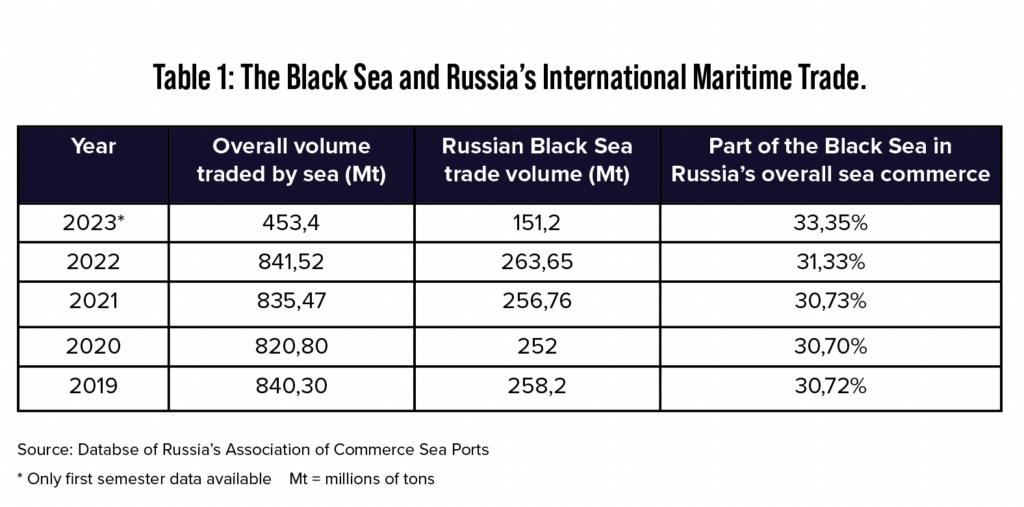

Russia’s military command likely considered two important aspects of any conflict scenario in the Black Sea region. First, the fact that the Black Sea is a critical economic outlet for Russia’s international sea trade (see Table 1). Around 30 percent of Russia’s overall international sea trade transits through its Black Sea ports, with Novorossiysk playing a key role as a terminal for oil and grain exports.[8]

This point appears critical since any conflict breaking out in the vicinity of Russia’s Black Sea coast would automatically create tensions for Russian sea trade. There is a direct and vital issue for Russia concerning the freedom of navigation for its international commerce across the Black Sea (and beyond), particularly for oil exports, which generates considerable revenue for the federal budget (28,3% for the 9 first months of 2023)[9]. Any deterioration of the maritime security context in the Black Sea zone, as it has occurred since last year, can exert pressure on maritime commerce, including exploding fares and insurance costs for tankers crossing the Black Sea (and not only for those transporting cargo for Russian firms). In this context, the BSF may be requested to ensure the security of transit for tankers leaving Russian ports.

The second aspect has to do with the Montreux Convention. Since February 28, 2022—four days after the conflict broke out—Turkey has hermetically closed navigation through the Turkish Straits for war vessels according to the Montreux Convention (Articles 19, 20, and 21). On the one hand, it has certainly made things easier for the BSF which has not had to cope with the naval presence of potential non-Black Sea countries’ NATO warships. But, on the other hand, Turkey’s approach has created logistical difficulties in supporting its own presence in the Mediterranean, while preventing any robust naval reinforcement of the BSF over the past twenty months. What is more, on February 24, 2022, two classic submarines of the BSF (the B-261 Novorossiysk and the B-265 Krasnodar), one frigate (Admiral Grigorovich), and one small missile corvette were deployed in the Mediterranean. Yet, according to Article 19 of the Montreux Convention, Moscow could have legally asked Turkey to allow the aforementioned units to return to their homeport.[10] Russia has refrained from doing so, however, most likely because it did not want to alienate Ankara. Indeed, according to Article 21 of the Montreux text, “It is understood, however, that Turkey may not extend this right to vessels of the State whose attitude would have motivated the application of the present article.”

Despite this interdiction, the BSF has received new units after the “special operation” began, including one corvette (Project 20380) which, being in the Mediterranean, cannot factually join the Black Sea naval theater until Turkey cancels the aforementioned restrictions.[11] New units, however, did join the BSF. The first small missile boat of Project 22800 was commissioned by the BSF last summer, with one more unit likely coming in line before the end of the year. These platforms are Kalibr capable and since they were built in Crimea, they are immediately available. One more patrol boat (Project 22160) was integrated into the BSF in summer 2022. It was also built in Crimea. Finally, before the beginning of its campaign, Russia had nevertheless reinforced the amphibious component of the BSF with six large landing ships (Projects 1155, 1171, and 11711) coming from the Baltic and the Northern Fleets. In other words, on the eve of the conflict, roughly 50 percent of the Russian Navy’s amphibious capacities were concentrated in the Black Sea. This rough percentage does not take into account vessels under repair, nor those going through various cycles of tests. Finally, up to three small missile boats of the Caspian Flotilla equipped with Kalibr cruise missiles may have been added to the order of battle of the BSF before the “special operation.” They were transferred through the network of channels between the rivers Volga and Don from the Caspian Sea and through the Azov Sea to the Black Sea. Other light units may follow in the future, using the Volga-Don channel. In sum, before the outbreak of the conflict, the BSF order of battle was enhanced thanks to inter-theater maneuvers which strengthened its amphibious potential and its firepower.

The Black Sea Fleet’s Posture: From Offensive to Active Defense

Since Ukraine did not have any capable naval force before February 24—the only capable frigate, the Hetman Sahaidachny, was scuttled in Nikolayev on March 3, 2022—and given the absence of a naval adversary on the Black Sea stage after Turkey closed the access to the Pontus Euxinus on February 28, the BSF carried out the operations that were, by nature, subordinate to operations on land. The bulk of the Ukrainian Navy was indeed stationed in Crimea and lost by Kiev during the operations which led in 2014 to the annexation of the peninsula. The scope of BSF’s missions includes combat and support tasks carried out in the Azov and Black seas. Those tasks have included in-depth strikes with Kalibr cruise missiles (up to 2,500 km range), which probably remain even today at the core of the combat missions of the BSF. Units capable of carrying out long-range cruise missile strikes have been regularly engaged together with land-based systems and air assets. According to some studies, sea-delivered Kalibr missiles represented around 12.5 percent of the overall missiles fired against targets in Ukraine from January 1 to March 31, 2023.[12]

There are no reliable statistics regarding the use and type of missiles fired since February 2022, and we can safely assume that missile strikes carried out by the BSF remain irregular over time. In the early stage of the conflict, Russia seemed to project a landing operation on the coasts of the Odessa region, to carry out what was initially supposed to be a combined offensive with ground units expected to progress across the Nikolayev and Odessa regions. The large landing ships sent in reinforcements prior to the conflict were later spotted off southern Ukraine, with pictures and videos of their silhouettes on the horizon appearing on social networks. However, this amphibious task force never carried out its supposed mission, as the situation on the ground did not unfold as expected, because the Ukrainians moored mines off Odessa to prevent any landing operation. One successful landing operation nevertheless was carried out on Snake Island, which fell under Russian control in the very first hours of the offensive. Large landing ships were furthermore involved in support missions and tasked with supplying equipment and vehicles by sea to troops operating in southern Ukraine. That was done in the early stage of the campaign by amphibious units crossing the Azov Sea to deliver their cargo in Berdiansk. One of them, the Saratov, was reportedly hit by a ballistic missile on March 24, 2022.[13]

After the cruiser Moskva was sunk in April 2022, surface units of the BSF started to operate at a greater distance from the Ukrainian coasts. Although the threat posed by surface drones supplemented, over time, the anti-ship missiles threat emanating from Ukrainian coasts, videos shared on Telegram channels in early summer 2022 already showed some platforms fired their Kalibr missiles from a rather short distance from Sevastopol’s harbor. Ukraine indeed started to absorb Harpoon anti-ship missiles as soon as early summer 2022 and had, apparently, a small stock of Neptune anti-ship missiles. Retrospectively, the absence of air supremacy from the Russian aerospace forces (or VKS) due to the air denial created by the combination of Ukrainian anti-air systems, limited aircraft activities, as well as the intelligence Ukraine has received from the West, caused a sea denial for the BSF, which has been compelled to operate much farther from the Ukrainian coasts. Starting from April 2022, when it became clear that the conflict would last longer than probably expected after the diplomatic track collapsed in Istanbul, the posture of the BSF morphed from an offensive to a de facto active defense posture to consolidate the territories conquered during the first weeks of the offensive. In wartime, active defense could be defined as “a military strategy [that] denotes operations premised on defensive maneuver, and a sustained counterattack throughout the depth of the theater of military action. It places strong emphasis on defensive and offensive strategic operations […] This envisions degrading an opponent’s forces via fires and strike systems, while parrying their initial offensive operations.”[14]

In the context of the Ukrainian counter-offensive, this posture has appeared relevant: the strikes and actions carried out by the BSF aim to destroy and disorganize Ukrainian logistics in order to weaken Kyiv’s ability to sustain its war effort against Russian lines of defense.

However, the emergence of the combined threats of surface drones and anti-surface missiles has not prevented the BSF from operating in the southwestern part of the Black Sea basin, as demonstrated by the boarding of a tanker bound for Ukraine last September.[15] This type of operation relates to another mission of the BSF: the blockade of the Ukrainian coasts. However, the combined effects of the drones and missile threats emanating from the regions of Odessa and Nikolayev, on the one hand, and the conclusion of the Grain Deal—or Black Sea Grain Initiative (BSGI), which entered into force in mid-July 2022—downgraded the geographical and operational scope of this mission. The three Ukrainian ports of Odessa, Tchernomorsk, and Yuzhny were protected by the provisions of the BSGI and a maritime security corridor was set to export Ukrainian grains while a monitoring center in Istanbul was created under the auspices of the United Nations. However, on July 17, 2023, Russia suspended its participation to the BSGI, claiming that Ukraine was using the maritime corridor to launch drone attacks on Crimea and started to strike Ukrainian ports and maritime infrastructure on the Black Sea and the Danube that were previously under the protection of the BSGI. The missile threat escalated during the summer of 2023 after Ukraine had received a batch of air-launched cruise missiles from the UK (Storm Shadow missiles) and France (SCALP missiles) fired from Ukrainian Su-24 aircrafts. These munitions have been apparently used against military targets in Crimea, such as ammunition depots, anti-air systems, and shipyards. On September 22, 2023, the BSF headquarters was reportedly struck by Storm Shadow missiles. A few days later, a shipyard was reportedly struck in Sevastopol, again by Western cruise missiles fired by Ukraine.

As the conflict has dragged on, the scope of the missions of the BSF has expanded to include the protection of military and civilian critical infrastructure exposed to surface drone attacks. Ukrainian surface drones have targeted Sevastopol, the Crimean bridge, and Russia’s naval base in Novorossiysk, as well as a Russian civilian tanker in early August 2023.[16] The BSF has been tasked with protecting the infrastructures on shore, but also with preventing a potential saboteur attack on gas pipelines running on the seabed of the Black Sea between Russia and Turkey, namely the Blue Stream and TurkStream pipelines. Russian officials claimed that attacks similar to the sabotage of the Nord Stream 1 and 2 pipelines were reportedly averted by BSF units.[17] It was during one of these monitoring missions that the intelligence ship Priazovye was targeted by a Ukrainian surface drone.[18] The platform that appears to play a greater role in detecting, searching, and destroying incoming surface drones from Ukraine is the patrol boat of Project 22160. Belonging to the separate division of patrol vessels of the 184th Water District Protection Brigade based in Novorossiysk, these four units built in the Gorki shipyards in Zelenodolsk (Tatarstan) on the Volga have demonstrated their relevance for this type of mission. Finally, large landing ships of the BSF were affected by the transport of civilians and their cars between Crimea and mainland Russia in summer 2022, in the context of regular drone attacks against the Crimean bridge. During the summer season, many tourists crossed the bridge back and forth to spend time on the peninsula, which created huge lines of vehicles on both sides when Russian authorities decided to close the bridge every time drones appeared or approached the area.

Russian Navy’s Black Sea Fleet logistics support ship Vsevolod Bobrov sails in the Bosphorus in Istanbul, Turkey January 7, 2022. Picture taken January 7, 2022.

The Black Sea Fleet Adapts

It is highly likely that the experience acquired and being acquired by the Russian navy in the Black Sea naval theater will serve as the backbone of the naval component of the country’s future armament program. The developments at sea since February 24, 2022 have shed light on challenges and threats the BSF has and will have to deal with in the foreseeable future. Mines and drifting mines appeared as soon as spring 2022 as not only a threat for Russian vessels, but also for all the shipping in the Black Sea. Ground-based and air-launched cruise missiles supplied by some Western countries posed a direct threat to Russian surface vessels and infrastructure in Crimea. This latter threat has been supplemented by naval drones (surface and probably underwater in the near future) and airborne unmanned aerial vehicles. In late spring 2023 and during summer 2023, while the Ukrainian army was carrying out a counter-offensive, Ukraine was also carrying out missile and drone attacks against civilian and military infrastructures and commercial and military ships. Supposedly, these attacks were also made possible by discreet hostile local actions of saboteurs or enemy special forces. Finally, the operational activity of NATO spy planes and drones in the immediate vicinity of Russian air and naval space, or considered as such, above the Black Sea has increased. This has posed a challenge to the Russian military and resulted in some dangerous interactions in the sky.[19]

To meet these challenges, the Russian Navy has already taken several measures and is likely to adopt others. In other words, it has been able to adapt within a few months to a new security reality at sea. Concerning the threat posed by drones, a number of countermeasures have already been adopted. These measures include the installation of nets and barges to protect critical infrastructure and potential targets; bombing campaigns targeting suspected drone storage, assembly, and production sites; and the use, with some success, of Project 22160 patrol boats projected as radar in the Black Sea (these platforms are also equipped with a Ka-27 helicopter) to detect drones and destroy them in close combat (with grenade launchers or MTPU-1 Zhalo heavy machine guns).

Future measures to consolidate this defense, again irrespective of the outcome of the conflict, could include the permanent deployment in the air of BSF naval aviation patrol aircraft. Possibly built based on the Il-114, it would be sufficient for one aircraft to fly over the basin to detect incoming drones. This mission could also be carried out by drones, such as the Forpost or the more recent Inokhodets, of which deployment could be combined with the action at sea for one or more patrol boats. The patrol boat could be employed in combination with Grisha III type anti-submarine warfare (ASW) vessels (to protect the Grisha III) which feature towed and immerged sonars.[20] Since noncombatant military platforms are the most vulnerable—as illustrated by the failed attempt to attack the Ivan Khurs intelligence vessel—it is to be expected that, in the future, they will be equipped with close-combat capabilities (GSh-23 type grenade launchers and KPVT heavy machine guns). In the medium term, we cannot rule out the possibility of Russia immerging a hydrophone system in the Black Sea (something similar to the American SOSUS across the Greenland–Iceland–United Kingdom gap) to detect in advance incoming surface and submarine drones. In the air, Russia could also dispatch a curtain of aerostats to detect approaching drones. The patrol boats and corvettes responsible for the in-depth tracking and the destruction of hostile units will themselves be equipped with surface and aerial drones. Given the spectacular leap forward made by Russian industry in the production of drones and their use by the Russian army at the tactical level, we cannot rule out the possibility that they will also be part of the response to the threat posed by naval surface drones. Last, one cannot, at least methodologically given that surface drones are launched from Ukraine’s Black Sea coasts, exclude that this will give an additional argument for those who, in the Russian military, certainly advocate for the conquest of all Ukraine’s coastal oblasts up to the Danube River. This would fit in the framework of the long “war of attrition” regularly put forward by some Russian officials for several months now.[21]

The recent announcement by the Abkhazian leader Aslan Bzhania that the BSF will be granted a naval support point in Ochamchire on the shores of Abkhazia can be, to some extent, considered a response to Ukrainian drone attacks on Crimea, Novorossiysk, and even against Sochi airport.[22] Yet, there are some limits to this plan. First, it’s been an old topic of discussion between Russia and Abkhazia since Moscow recognized this territory as independent from Georgia in 2008 following the Russo-Georgian war. In early October 2023, it was reported that an agreement was signed regarding the creation of a “naval base” in Ochamchire, on Abkhazian coasts[23]. Second, given the geographical specificity of the considered site (the Ochamchire area), it can harbor a maximum of a few patrol boats or small missile boats, but in any case, it cannot be considered as a Plan B to relocate the units deployed in Sevastopol. The two sites cannot just be compared in terms of size and infrastructure. Third, the Black Sea coast of Abkhazia provides Russia with some sort of strategic depth. During World War II, as the Germans seized Crimea and Novorossiysk, they were never able to reach the Georgian coasts where the Soviet BSF escaped.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky has visits Snake Island on Saturday July 8, 2023 as the conflict reaches its 500th day. Moscow captured Snake Island shortly after launching its invasion on February 24, 2022 but Ukraine liberated it on June 30, 2022. The Russian ship involved, the Moskva, sank in the Black Sea in April following what Moscow said was an explosion on board.

A Potential Post-Conflict Black Sea Fleet

Irrespective of the outcomes of the “special operation,” the post-conflict BSF should have an enhanced littoral component with an emphasis on long-range cruise missile capabilities, possibly hypersonic. This would be consistent with Russia’s industrial capacities and possibilities constrained by the sanctions, as well as its traditional focus on littoral waters, and firepower. Of course, the BSF will retain some limited high-sea capabilities with the Project 11356 frigates, and one cannot exclude that one or two Project 22350 frigates will be transferred to the BSF, with their Tsirkon hypersonic missiles. The littoralization of the BSF was a tendency already observed before February 24, 2022; the conflict has just accelerated it. Moreover, even littoralized, the BSF would still retain the ability to project power beyond close sea zones[24] and toward remote maritime zones,[25] like the Mediterranean or the Red Sea. Accordingly, we should see more Project 22160 patrol boats (1,000 tons of displacement)—with enhanced detection capabilities—and Project 22800 small missile boats (2,000 tons of displacement). They can be supplied through internal waters and can therefore reinforce the order of battle of the BSF regardless of the closure of the Turkish Straits. At a later stage, once the Straits are open, it is expected the BSF will receive at least one Project 20380 corvette and one Project 20386 heavy corvette.[26]

The naval development of the conflict in Ukraine may furthermore act as a wake-up call for the Russian Navy in general regarding naval aviation. The modernization of the Il-38N maritime patrol aircraft equipped with the Novella suite has begun, but it is certainly not sufficient. Likewise, the ASM Minoga (or Ka-65) combat helicopter program seems to have been shelved for the time being but is likely to return. However, since the fleet is a priori unlikely to be prioritized in the next armament plan, the funds that will be affected to the Navy in general should support the expansion of the littoral fleets in particular. This will be done to the detriment of heavy surface units, and here, the downfall of the Moskva will probably influence decision-makers. These lessons learned from this latter episode will probably be confirmed by the tremendous cost of the overhaul and modernization of the ex-Soviet nuclear-powered missile cruiser Admiral Nakhimov (Project 1144, 26,000 tons)—200 billion rubles, or nearly $2 billion.[27] This probably will play against large surface programs, at least those bigger than the frigates of Project 22350 and Project 22350M (as the program of a new destroyer, the Project 23560, which seems to have been mothballed since the late 2010s). The money saved could serve to finance the overhaul of the surface anti-submarine component which has been aging (Project 1124 Grisha in their various derived versions).

Conclusion

Russia’s BSF has adapted to its contested supremacy in the Black Sea maritime theater. At this stage of the confrontation between Russia and Ukraine, the adaptative measures already taken by the BSF put the emphasis on littoral warfare. The littoralization of the BSF has been at play during the last decade, and the conflict in Ukraine has reinforced, if not catalyzed, this trend. The actual industrial, financial, and capability context already plays in favor of the constrained reinforcement of the littoral fleet (in the Baltic and Northern fleets especially), with the prioritization of the construction of small missile boats, corvettes (although heavy ones), and frigates, capable of being deployed on the high sea, according to Russian Navy practices. Therefore, it is expected that, despite the context where the navy should not be the priority of the next armament program covering the end of the 2020s and the beginning of the 2030s, the BSF should nevertheless be primarily regenerated according to the lessons learned from the conflict.

No comments:

Post a Comment