Bruce Gilley

Japanese sub-hunting helicopters have recently been training with their American allies in the Pacific to defend Taiwan from a possible invasion by China. There is a certain irony. After all, it was Japan’s full-scale invasion of China in 1937 that opened the way for the communist takeover of China, eventually forcing the retreat of the republican government to Taiwan. The result was “two Chinas” and an enduring conflict between the two sides. The Japanese, it seems, are making amends for their contribution to this historical disaster.

So are the Americans. With the help of useful idiots like the journalist Edgar Snow and the agronomist William Hinton, American opinion-makers of the 1940s came to see the communist rebels as more virtuous and progressive than the Kuomintang government of Chiang Kai-shek. American academics then lavished praise on Mao in the early years of the People’s Republic, which kept the refounded Republic of China on Taiwan on edge. If Mao had invaded Taiwan after China went nuclear in 1964, the U.S. might not have intervened.

Once the true horrors of Maoism began to emerge, U.S. policy shifted decisively in support of Taiwan. “How little we knew about China!” began a doleful 1981 article by Professor Edward Friedman, a former Mao-worshiper at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. The 1979 Taiwan Relations Act that protects the island from the Reds might better be called the “Sorry For Believing Leftist Myths About Mao and Destroying the Republic of China Act.”

The so-called “republican” era in China’s history usually refers to the years 1912 to 1949, when the first and only experiment in liberal modernity took place in China under the Kuomintang. The era has been widely derided by communist and leftist historians as rife with poverty, corruption, and disorder. For them, the coming to power of the CCP was the fulfillment of the March of History, the arc of social justice.

That image is patently unsupported by the facts, says Xavier Paulès, Director of the Center for Modern and Contemporary China Studies at France’s Institute of Social Studies. In this book, published first in French in 2019, Paulès makes the case that the republican era witnessed major progress on all fronts—economic, social, and political. That progress was substantive and institutionalized, unlike the flights of revolutionary fancy in the communist base areas that won the praise of Western intellectuals. The foundations of a modern, industrial economy were laid and a flourishing capitalism emerged. The distinctively Chinese form of the modern state that still obtains on Taiwan was created with five branches of government (executive, legislative, judicial, civil service, and anti-corruption). Classical culture was nourished while social progress (especially for women in the banning of polygamy and foot binding and the entry of women into the bureaucracy) leaped ahead. Civil society flourished, elections were held, and the bureaucratic state began to provide public health, education, infrastructure, policing, prisons, divorce, and statistics.

The old communist claim about peasant impoverishment, meanwhile, is a myth. The population is said to have risen from 410 million to 540 million, and a new urban middle class emerged. “There is no serious empirical evidence to support the thesis of a generalized impoverishment of the peasants, nor of a trend towards concentration of land in the hands of landowners,” Paulès writes. In other words, communism in China was built on a false premise.

That this noble experiment ended was mainly attributable to the Japanese invasion, Paulès argues, which forced the KMT into a war posture that undermined its modernization project. The CCP was of “mediocre size and importance” until the Japanese helpfully cleared a path for its conquest of northern China. Add in Soviet aid to the CCP and the tactical mistakes by the KMT in the civil war of 1945 to 1949, and the Stumbles of History became the March of History.

Paulès’s book makes it easy to imagine a KMT that held onto the portion of southern China roughly defined by the Yangtze River. Shanghai and Canton, not to mention Tibet, Taiwan, and later Hong Kong, would have remained part of what came to be called “free China.” Tens of millions of lives would have been saved and bettered. A major geo-strategic competitor to the U.S. would have been confined to the dry flatlands of northern China. The Republic of China, like the Republic of Korea, would have outshone the communist sclerosis in the north.

The good news, in the view of Paulès, is that today’s China looks a lot more like the modernizing KMT than it does the impoverishing CCP under Mao. The restored place of Shanghai as the nation’s undisputed cultural and economic center reflects the triumph of republican China’s ideals in China, he believes. China has “completely turned its back on its revolutionary origins.”

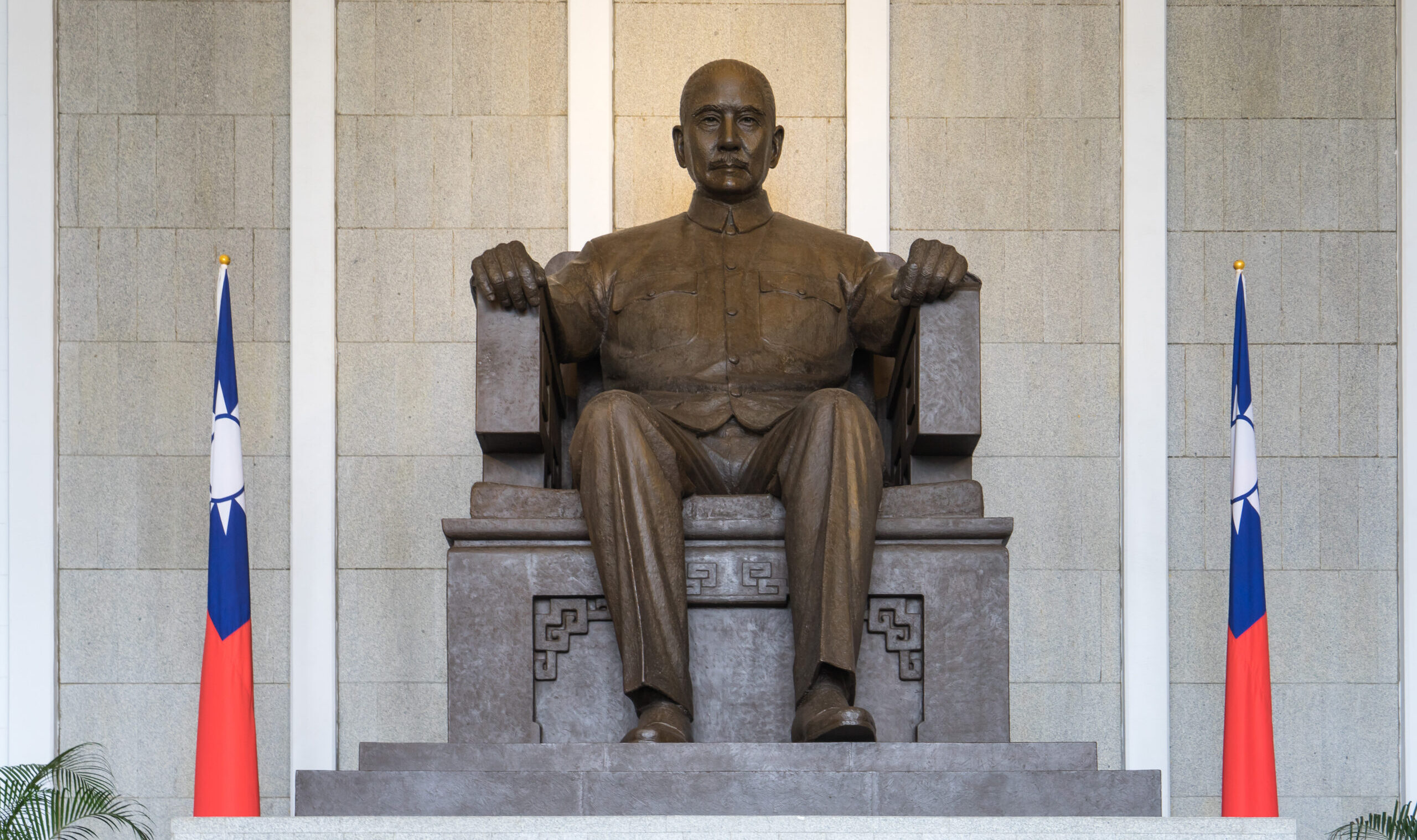

To be sure, the CCP, which openly venerates republican founder Sun Yat-sen, has made peace with that era and borrowed from its success. It has given up controlling markets, allowed social autonomy, and built a legal system.

But is it too much to assert that the CCP has changed its spots? Paulès goes into some detail to explain why the KMT itself never qualified as a revolutionary regime of the right. This question came suddenly back into fashion among academics during the global moral panic of the Trump era. Cambridge University Press rushed out a book by the Hong Kong scholar Brian Tsui titled China’s Conservative Revolution, which claimed to shed light on today’s “rise of far-right politics” including Trump. The KMT, Tsui wrote, had committed the cardinal sins of “opposition to social revolution” and “shielding the system of private property from political intervention.” Its youth movement and nationalist rhetoric drew inspiration from Hitler.

Paulès shows these claims are ludicrous. The KMT was conservative but not fascist. There was no all-powerful state controlling society, no mass indoctrination, no mass movements, little censorship, and hardly any police suppression of political opposition. There was no “New Man” being forged from the crooked timber of Chinese humanity, and the youth movements were a sideshow. The KMT held elections, allowed a flourishing media, and left businessmen to themselves.

Can the same be said of today’s CCP, as Paulès claims? While Tsui saw a fascism in the KMT where none existed, Paulès might be charged with seeing a moderation in the CCP that does not exist. Censorship, crushing opposition, mass indoctrination, and the all-powerful state remain. I’ll need more convincing to think that today’s CCP is an inheritor of the liberal, modernizing legacy of the KMT.

The continuation of “free China,” both in historical inquiry as well as in practice, in Taiwan matters greatly. While China may try to invade Taiwan, there is also a non-trivial possibility that China may fall apart before it has a chance. Just as the Qing dynasty collapsed into the arms of the KMT’s predecessor organization in 1912, the communist dynasty may one day need help from the KMT’s successor state on Taiwan. That’s a teleological March of History that I could buy into—one in which liberal governance triumphs over illiberal rule.

Actual history will be different, of course. But the 75 years since 1949 have been far kinder to the Chinese people living under republican rule on Taiwan than to their compatriots warped by the ferocious illiberalism of communism on the mainland. The eminent Taiwan scholar Lee Kung-chin published a book in 2017 titled The Turbulent Hundred-Year History of the Republic of China showing how republican rule has steadily adapted to new challenges and been self-critical enough to respond to social needs. Those Japanese helicopters prowling for Mao’s subs in the Pacific alongside American flattops are part of a bigger historical drama. They keep alive the only chance the Chinese people have ever had to be free.

No comments:

Post a Comment