Patricia M. Kim, Kevin Dong, and Mallie Prytherch

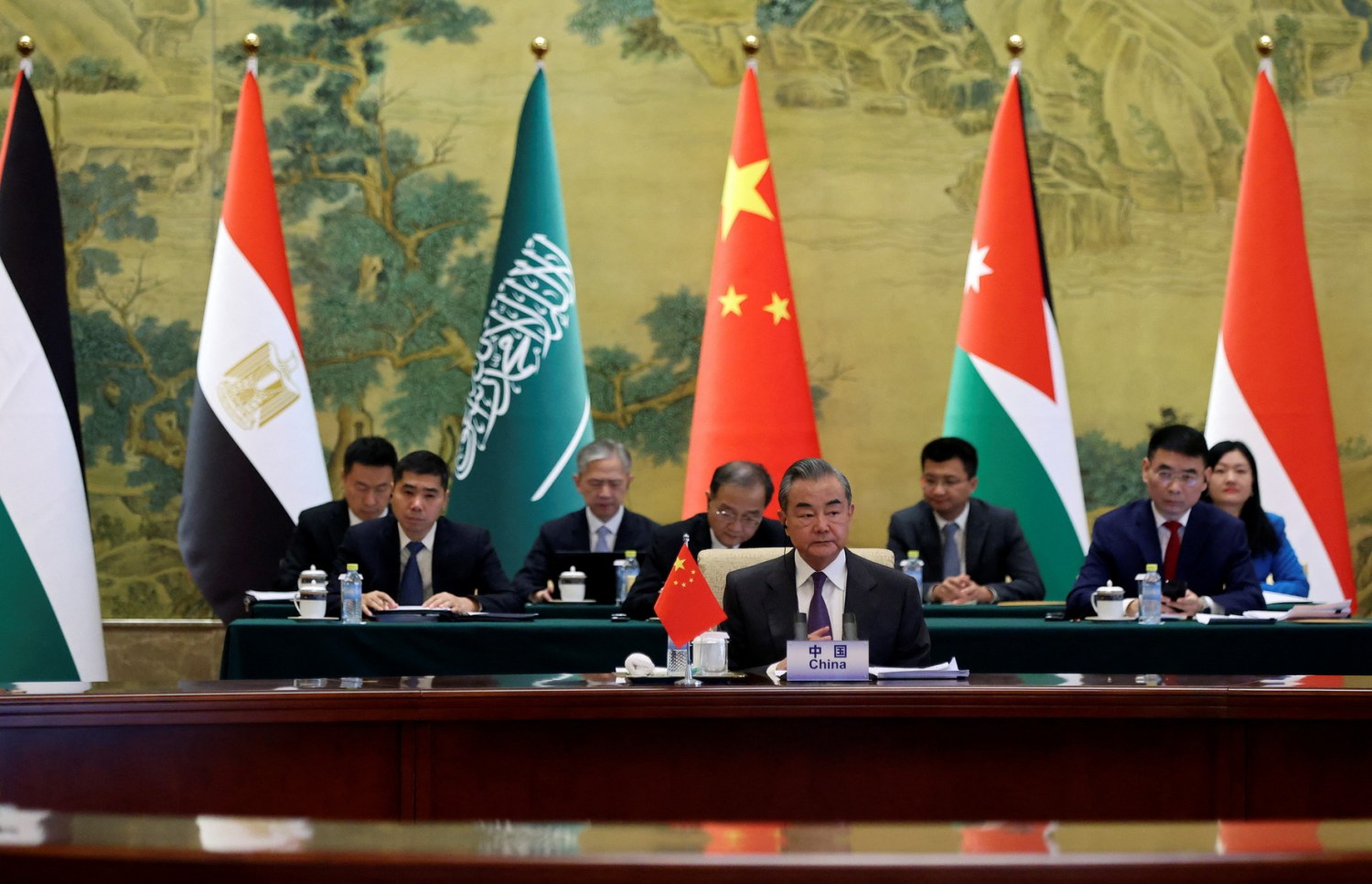

Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi attends a meeting with Saudi, Jordanian, Egyptian, Indonesian, Palestinian, and Organization of Islamic Cooperation delegations at the Diaoyutai State Guesthouse in Beijing, China, November 20, 2023.

How is China responding to the Israel-Hamas war?1 Since Hamas’ October 7 terrorist attack on Israel and the subsequent Israeli strikes on Gaza, Beijing has positioned itself as an advocate for peace, calling for an immediate cease-fire in Gaza and the establishment of an independent Palestinian state while criticizing the United States’ support for Israel. In the weeks following the attacks, China hosted the foreign ministers of four Arab states and Indonesia. The fact that the delegation chose Beijing as its first stop was heralded by Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi as a sign that “China is a good friend and brother of Arab and Islamic countries.”

While more than 10 Chinese nationals have been killed, injured, or reported missing as a result of the crisis, the Israel-Hamas war has not, however, generated much of a public reaction in China. In fact, a close examination of Beijing’s official statements and activities, commentaries in state media, and social media narratives around the Israel-Hamas war reveals that while China seeks to portray itself as a proponent for peace and to signal its alignment with many non-Western states in advocating for the Palestinian cause, it remains reluctant to assume a substantive role in the ongoing conflict.

Parsing official Chinese statements and diplomatic activities

Official Chinese statements on the Israel-Hamas war have centered on expressing broad concern around the conflict’s escalation and its humanitarian consequences. Beijing has not explicitly condemned Hamas’ terrorist attacks while stressing that only a political settlement and a two-state solution can ultimately solve the conflict between Israel and Palestine.

Chinese President Xi Jinping commented publicly for the first time on the crisis nearly two weeks after the October 7 attacks on the sidelines of the Belt and Road Forum. In a meeting with Egyptian Prime Minister Mostafa Madbouly, Xi called for a permanent cease-fire and the need to prevent the conflict from spiraling out of control. His remarks that a two-state solution and establishing an independent State of Palestine are the “only viable way” to resolve the longstanding conflict between Israel and Palestine were again reiterated in his speech at an extraordinary BRICS summit on the crisis the following month.

In the early weeks of the crisis, Wang spoke with his counterparts in the Israeli government and the Palestinian Authority (PA), in addition to Saudi Arabia, Iran, Turkey, Russia, and the United States. A comparison of the official Chinese readouts of these meetings provides a window into how Beijing seeks to position itself publicly amid the crisis. For instance, the summary of Wang’s call with PA Foreign Minister Riyad al-Maliki adopts a considerably warmer tone, starting with Al-Maliki’s “heartfelt thanks to China” for “standing firmly with the Palestinian people” and a summary of the PA’s position.

In contrast, the readout of Wang’s call with Israeli Foreign Minister Eli Cohen simply notes that Cohen gave “an update on Israel’s position” to China. Wang is then quoted lecturing his Israeli counterpart that “All countries have a right to self-defense, but it is important to observe humanitarian law and protect civilians.” Wang notes that “only by adhering to common security can sustainable security be achieved” — a core theme of Beijing’s “Global Security Initiative.” Beijing has employed this argument with greater frequency in recent years to criticize the United States and its allies for pursuing “individual security” at the expense of “common security,” and to lend diplomatic support to Moscow, Pyongyang, and other “victims” of Western containment.

Although Beijing and Washington theoretically share a mutual interest in preventing the spread of conflict in the Middle East, there seems to be little, if any, coordination between the two sides on the crisis. At the United Nations, the United States and China have stood at a crossroads. The U.N. Security Council has failed on four separate occasions to pass a resolution related to the Israel-Hamas war due to vetoes by the United States, China, and/or Russia. China has vetoed a U.S.-sponsored draft resolution for failing to call for an immediate, permanent cease-fire, while the United States has vetoed resolutions for failing to condemn the attacks of October 7 and not mentioning Israel’s right to self-defense.

China has taken steps to bring attention to this division — for instance, Chinese Ambassador to the EU Fu Cong stated that “there are many countries who obviously do not see eye to eye with Europe in terms of values … We can clearly tell from the divergence of responses to the ongoing Gaza crisis.”

Eschewing a leading role in the conflict

Even as China has expanded its diplomatic footprint in the Middle East — most notably helping broker a deal between Saudi Arabia and Iran to restore relations last March — it has not sought to assume a leading role in the ongoing conflict in Gaza. In late November, Beijing released a five-point position paper in which it calls for an immediate cease-fire, the protection of civilians, and the ramping up of humanitarian assistance.

The paper also calls for “countries with influence on parties” to help deescalate the crisis and for an international peace conference to draft a “concrete timetable and roadmap” to implement a two-state solution and a “just and lasting solution to the question of Palestine.” Quite notably, the paper explicitly calls for the U.N. Security Council or the U.N. to take the lead on advancing each of the five points. Nowhere is there a reference to Beijing’s offer from last spring to mediate between Israel and Palestine.

Last week, Wang began his first foreign trip of the year in Egypt, where he expressed China’s support for a “larger-scale” international peace conference, stating the details of the conference would be “determined by all parties,” and for the United Nations to play an “active role” in the process. Despite growing global concerns about the Houthis’ attacks on commercial shipping in the Red Sea and China’s economic stakes in the region, Beijing has shown no interest in directly addressing the mounting crisis other than declaring its opposition to the harassment of civilian ships and obliquely criticizing U.S. and British airstrikes against Houthi-controlled sites in Yemen.

Narratives in state-owned media

Chinese state-owned media has leaned into using the crisis to cast Washington as the driver of instability in the Middle East. Many of these articles point to the United States’ “hegemonic behavior,” its history of military interventions in the Middle East, and its “biased” support for Israel as key drivers of the current conflict. For example, one editorial in the Global Times states that the United States and Europe’s inability to “uphold the existing world order” and their “marginalization of the Palestinian issue” are the driving factors in the current conflict. Another blames the United States and some of its Western partners for “add[ing] fuel to the fire” and for “seeking absolute security” for themselves “under the guise of peace.” These critiques parallel Chinese accusations that the United States is “fanning the flames” in the Russia-Ukraine war by providing Ukraine with lethal assistance.

Domestically, state-owned media has gone further. In one instance in early October, a China Central Television social media account reposted a clip from coverage of the 2020 U.S. presidential election. It included several antisemitic conspiracy theories, including that “Jews influence the U.S. government through money and votes.” The social media clip went on to utilize the hashtag “占美人口3%犹太人操纵七成美国财富,” or “Jews represent 3% of the U.S. population but control 70% of the U.S. wealth.”

Narratives in Chinese social media

Weibo, often described as a Chinese version of X (formerly known as Twitter), is one of the few remaining gauges of Chinese public opinion despite substantial censorship of its content and the heavy presence of government-sanctioned posts. A few weeks after the outbreak of the conflict, there were 12 trending topics/hashtags related to the Israel-Hamas war that were read by at least 250 million people (see Table 1). Interestingly, most of the trending topics focused on Israel rather than Gaza, Hamas, or Palestine, although whether this reflected genuine user interest or curation efforts by censors is difficult to determine. Videos and photos of attacks committed by both Israel and Hamas were rampant, although more posts highlighted atrocities committed by Israel. Posts that discussed terrorism by Hamas were not censored, however, and received both sympathy and condemnation from netizens.

Narratives in Chinese social media

Trending topics/hashtags related to the Israel-Hamas war that were read by at least 250 million people on Weibo

Widespread posts and discussions showed a general lack of sympathy for Israel’s security and territorial rights. The argument that China does not “owe” Israel any apologies or special support gained significant traction in response to Israeli expressions of disappointment over China’s stance on the conflict. A video of the Israeli ambassador referencing the Old Testament to assert Israel’s right to its land was ridiculed, with some netizens sarcastically suggesting that according to such logic, China could then use historical literature like 山海经 (known in English as Shanhai Jing, or “The Classic of Mountains and Sea”) to claim the entire world.

Another prevailing narrative pointed to the United States as the primary instigator and perpetuating force behind the current conflict. Though this sentiment was not as pervasive on social media as it is in state-owned media, many netizens pointed to U.S. interventions in the Middle East and its unwavering support for Israel as factors exacerbating the crisis.

Although four Chinese nationals have been killed, six have been injured, and two have been reported missing since the outbreak of the current conflict, the tragic news has received relatively little attention among netizens. While censorship likely contributes to the muted response on Chinese social media, the lack of a major societal reaction and demands for the government to take action suggests a relative detachment by the broader Chinese public from the ongoing crisis.

The postings that remain uncensored are primarily those that reference the casualties while supporting the government’s official position that calls for a cease-fire and the ultimate adoption of a two-state solution. One such popular Weibo post states: “Causing the death of Chinese people is unforgivable. Hamas indeed should not lead Palestine, but Palestine really has no other choice. But this does not mean that we should support Israel one-sidedly. We should look at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ point of view: armistice negotiations and implementation of the two-state solution.”

A specific case that has stirred attention on social media involves a kidnapped Israeli woman of Chinese descent, Noa Argamani, whose mother called on the Chinese government to secure her release. Many netizens expressed little sympathy for the woman and instead criticized her mother for “presumptuously” asking Beijing for help. Neither Chinese state media nor official government channels commented on the situation, despite the post of the mother’s plea garnering over 260 million views on Weibo as of October 25, 2023.

As with most social media platforms, there are also extreme, antisemitic views circulating on Chinese social media. For example, conspiracy theories like “Project Pufferfish,” which alleges a Jewish plot in conjunction with Imperial Japan to settle Northeastern China, have gained traction. Likewise, the arguments that “only Palestinian youths are civilians” and that Israeli youths do not deserve the same protections given Israel’s military service requirements are among the inflammatory perspectives found on Weibo.

A “diplomatic power broker” in name only

The Israel-Hamas war has sparked impassioned reactions in the United States and across Middle Eastern nations, where public protests, debates, and vigorous demands for government intervention have been prevalent. In stark contrast, neither Chinese leaders nor the Chinese public envision a major role for their government in the ongoing crisis.

A public opinion poll conducted by Tsinghua University’s Center for International Security and Strategy in November 2022 showed only 3.3% of Chinese believe peace in the Middle East should be China’s top international priority. In fact, it was the lowest-ranked issue in the poll, trailing far behind other topics such as pandemics, territorial disputes, and U.S.-China relations. While this poll predates the current crisis, it is highly likely that if it were conducted again today, the Middle East would rank far behind other key issues.

These findings suggest that while Beijing will not pass up the opportunity to use the current and future crises to discredit the United States while amplifying its alignment with its non-Western friends, it is likely to remain a nominal power broker in the Middle East by choice for the foreseeable future.

No comments:

Post a Comment