Qiheng Chen

In late 2022, the arrival of ChatGPT sparked a nationwide fervor in China to build similar indigenous generative artificial intelligence models and downstream applications. Unlike earlier breakthroughs in machine learning, which are task specific, the large language models (LLMs) that form the backbone of ChatGPT and other generative AI systems are general purpose in nature. They acquire human-like natural language understanding by training on a massive amount of data and then being fine-tuned.

Generative AI poses immediate political, regulatory, and security-related challenges for the Chinese government. The technology’s ability to generate and disseminate information threatens the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) control over information and raises concerns about privacy, safety, and fairness. At the same time, AI is front and center in U.S.-China technological competition. The technological know-how, often dual use in nature, not only fosters spillovers to the broader economy but also finds relevance in military applications. Beijing recognizes the risk of missing out on these opportunities. Consequently, China is committed to establishing the necessary conditions for catching up on this technology frontier, including tapping into generative AI’s potential to boost economic productivity and drive scientific progress in other disciplines.

This issue paper takes stock of developments in China’s domestic governance of AI over the past year and analyzes both the known aspects and the uncertainties surrounding China’s regulatory approach to generative AI.

Review of Developments in 2023

China currently regulates tech firms using a three-part framework of security, privacy, and competition; each pillar has a seminal law and a set of regulations. In June 2023, the State Council of China published a legislative plan that set a goal of presenting a draft comprehensive Artificial Intelligence Law to the National People’s Congress. Several sources suggest that the first draft may not materialize until late 2024. Until then, the AI space will be governed largely by ad hoc regulations.

The technological traits of generative AI require the Chinese government to elucidate how existing regulations would apply to them and fill the policy void where necessary. To date, regulation on generative AI — and on AI algorithms more broadly — has been led by the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) through piecemeal regulation. These regulations are targeted and problem-driven, addressing specific issues as they surface. To illustrate China’s current regulatory toolbox and approach, the rest of this section introduces the CAC’s three most relevant regulations, with an emphasis on the Interim Measures for Generative AI.

A Trilogy of Regulations on Algorithms

The three regulatory measures described here, which collectively establish the regulatory toolbox for generative AI, originated in response to the regulatory vacuum left by fast-changing technologies. Together, they function as substantive regulations on AI products and services in China in the absence of a general law on AI.

The first regulation is the Internet Information Service Algorithmic Recommendation Management Provisions (Provisions on Algorithms). This regulation, which became effective in March 2022, sought to address public discontent over price discrimination by e-commerce platforms and algorithmic exploitation of delivery workers, among other questionable practices. Notably, this regulation establishes a mandatory registration system for algorithms with public opinion properties or social mobilization capabilities. Companies must file information about their service forms, application fields, and algorithm types, as well as algorithm self-evaluation reports. At the time of this writing, the CAC had published six batches of registered algorithms from Chinese and foreign companies. Before the batch announced in April 2023, 85% of new registrations were personalized recommendations or search and filtering algorithms. Since then, the number of generative algorithms has increased more than tenfold, with 16 of them LLMs from Chinese providers.

The second regulation, the Internet Information Service Deep Synthesis Management Provisions (Provisions on Deep Synthesis), which took effect in January 2023, was released after deepfake images proliferated on the internet, breeding fraudulent activities. The regulation’s provisions define deep synthesis as technologies using generative and synthesizing algorithms (e.g., deep learning, virtual reality) to produce text, images, sound, video, and virtual settings. This was China’s first foray into regulating generative AI, with a narrow focus on the technology’s potential to generate misinformation and deepfake content. The provisions also include new mandates that deep-synthesized information must be labeled and that service providers must assume responsibility for protecting personal information in training data. These mandates are the bedrocks of China’s approach to regulating general-purpose AI.

However, ChatGPT and competing language models soon proved their use in cases beyond synthesizing images and creating human avatars. Industry experts envisioned a transition from “+AI,” where AI enhances productivity by performing a specific task, to “AI+,” where AI becomes the foundation around which workflows coalesce.

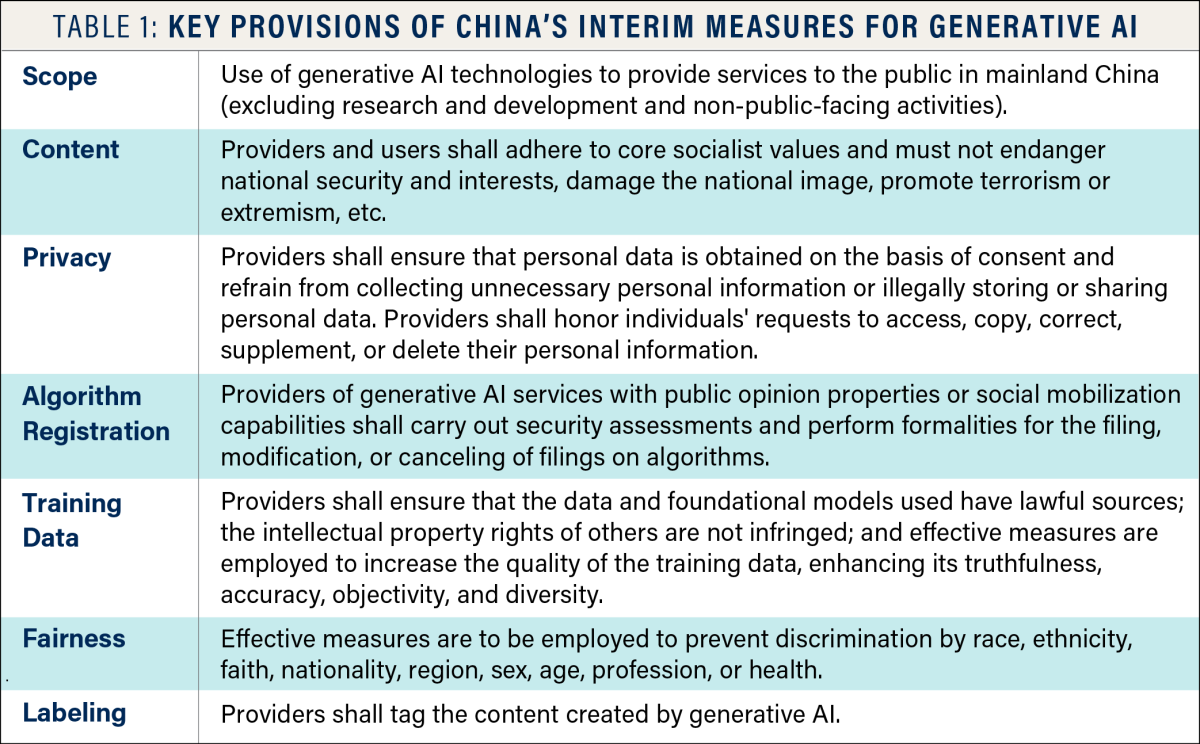

The third and most important regulation for general-purpose AI is the Interim Measures for Generative AI (Interim Measures). The CAC released the Interim Measures in July 2023 after a fast-tracked public comment period. The initial draft for comment was a makeshift effort intended to assert control over content generated from LLMs and provide directional clarity on how existing laws and regulations apply to generative AI as a slew of firms entered the space. The Interim Measures saw important changes from the initial draft, such as an explicit clarification that the measures do not apply to research and development or to non-public-facing activities. These changes signaled a policy environment that encourages AI innovation and adoption while still allowing the Party to retain control over information. Table 1 summarizes key provisions of the Interim Measures.

Emerging Contours of the Chinese Approach

Against the necessity of maintaining political alignment with the Party’s ideology, China’s approach to general-purpose AI has also sought to encourage domestic innovation as a primary focus. This focus is both an economic and a political requirement in the context of the technological rivalry between the United States and China. Although clear policies and precedents in various facets of AI governance have yet to be established, recent developments over the past year have begun to paint the contours of China's evolving approach.

Risk-Based Approach to Improve Regulatory Efficiency

Although no regulation has formally laid out a risk-based framework, one can infer the risk appetite of the Chinese government, whose top priority is to retain control of information. The Interim Measures specify that generative AI products and services must not contain information contrary to “core socialist values,” and public-facing generative AI products and services must undergo a security review and register the underlying algorithms with the CAC. In comparison, providers face lighter ex ante responsibilities for other risks of AI systems. For example, algorithmic discrimination is prohibited, and preventive measures must be taken throughout the life cycle of AI systems. However, the ban on algorithmic discrimination is not accompanied by mandatory conformity assessment by third parties; instead, it is up to providers’ internal compliance and risk management functions to audit AI systems.

A national-level risk-based approach would work most seamlessly with provincial measures. Several measures from economically advanced localities have advocated for risk-based regulations. The AI Industry Promotion Measures of Shenzhen, for example, proposed implementing a categorized and graded regulation based on new characteristics of the technology, ecosystem, and business model of AI.

Views from civil society appear to resonate with this risk-based approach. Researchers at the state-affiliated Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS) released a Model Law on AI, whose risk-based approach resembles the European Union’s AI Act. The Model Law proposes establishing a state body that would be responsible for regulating AI and implementing a negative list mechanism that would subject high-risk applications to a licensing requirement. The negative list would consider the significance of AI in economic and social development as well as the potential harm to national security, the public interest, and the legal rights and interests of individuals and organizations. Given the high regard for CASS by government officials, the Model Law could become a key input to the drafting process of China’s eventual AI Law.

In fact, a work process for establishing national standards to categorize algorithms and designate risk levels is already underway. Foundation models whose end use cannot be fully predicted in advance pose novel challenges in algorithm classification. Carving out algorithms with social mobilization is only the first step. A comprehensive classification of AI systems will inevitably consider not just the assessment of risk levels associated with end applications, but also the versatile nature of foundation models, the sensitivity of the training data and user inputs, and the scale of the AI models and their user base. Ongoing efforts to categorize algorithms will continue to shape and inform the risk-based approach that China is adopting.

Innovation Bias

Developments in the past year have demonstrated Beijing’s pro-growth stance, as evident in the Interim Measures as well as a landmark court ruling granting copyright protection to AI outputs. The Interim Measures, reflecting inputs from scholars and industry stakeholders, have introduced several new articles, underscoring China's ongoing efforts to foster a pro-innovation environment. For example, Article 6 promotes the sharing of computing resources, open access to high-quality public data, and adoption of secure and trustable chips.

In an attempt to balance regulatory requirements with industry feasibility, the Interim Measures have also been modified to reduce the compliance burden on generative AI service providers. For example, the initial draft required providers to fine-tune models within three months of knowing that certain content had become outlawed. This creates financial costs for providers as they must regularly adjust their models beyond the normal development cycles and provide continuous support for legacy models. However, the Interim Measures now offer more flexibility, having removed the rigid three-month window for fine-tuning models and acknowledging other viable methods for content filtering, thus reducing the operational strain on service providers.

The Interim Measures have also been updated to better reflect the inherent characteristics of LLMs. The original mandate to “prevent fake information” has been revised to “enhance transparency and reduce harmful fake information.” This change adds nuance by acknowledging that even the most advanced generative AI model is not immune to “hallucination” — the tendency for models to generate fabricated information in scenarios of uncertainty.

Retrospectively, the implementation of China’s Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL) in 2021 offers a useful lesson in how nimble policy design could mitigate negative effects on innovation stemming from stringent regulations. While the PIPL borrowed elements from the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), Chinese legal experts have been comparatively cautious about not stifling innovation, as they are keenly aware of the GDPR’s potential negative impacts and the disproportionate burden that it places on smaller enterprises. Chinese regulators chose to gradually tighten PIPL enforcement, initially focusing on a consortium of major apps.1 Doing so not only advances privacy protection goals, but also levels the playing field between dominant and smaller apps. This approach indicates a preference for gradual, targeted enforcement of regulation. The lessons learned from privacy protection could be applied to broader governance of AI, including LLMs.

Another issue that could impact technological innovation is how the nature of generative models presents challenges to existing copyright frameworks. LLMs, which are trained on extensive data sets typically sourced from the internet, may infringe on the copyrights of the original content creators. China mandates the legal acquisition of training data. However, the government has been exploring ways to avoid the high costs of data procurement, which can impede model development and amplify the advantage enjoyed by incumbent data controllers. The draft three-year action plan on data factors, issued in December 2023, encourages the development of common data resource databases by research institutions, leading enterprises, and technical service providers, while also fostering the creation of high-quality data sets for AI model training. The action plan represents the first substantial policy introduced by China’s National Data Administration; additional policies are expected in the future to stimulate data-driven innovation.

In addition to training data, there is a question of whether model outputs should enjoy copyright protection. China is advancing toward recognizing copyrights for user-generated content produced by LLMs. A landmark decision by the Beijing Internet Court in late 2023 acknowledged copyright in AI-generated images, citing the original human involvement in adjusting AI prompts and parameters as a basis. This decision diverges from international precedents. Conversely, the U.S. Copyright Office has refrained from granting copyrights to AI-generated content, drawing parallels between human instructions to AI models and directions given to a commissioned artist. If upheld, the Beijing Internet Court’s decision could foster artistic creation, thereby increasing demand for generative AI applications. However, this development may also raise concerns about the practicality of enforcement and the long-term cost on human creativity.

Share of Responsibilities Along the Value Chain

The supply chain of AI products and services generally consists of upstream providers of the technology infrastructure, downstream application developers, and end users. The ideal regulatory regime would allocate duties to those actors best capable of fulfilling them. Overregulation either upstream or downstream could stifle innovation and lead to undersupply of products and services. Specifically, excessive responsibility imposed on AI infrastructure providers would raise entry barriers for smaller firms, entrenching the power of a few big incumbent players. Excessive responsibility on downstream developers, by contrast, could result in fewer applications or a narrower range of product features available to end users.

The Interim Measures notably grouped upstream technology and downstream application developers into a single category of “providers” and imposed transparency requirements on them. Providers must release necessary information that affects user trust and choice. This could cover a range of information, including training and fine-tuning data, human labeling rules, and details of the technology stack being deployed.

Further clarification of the responsibilities of each group along the value chain is still lacking. Providers of proprietary general-purpose AI models may decline to share details of their models because of competition or trade secret concerns, limiting the ability of downstream players to fulfill their transparency obligations. These foundational model providers could also be in a position of power to offload responsibilities through contracts signed with downstream customers, which regulators around the world seek to prevent. The eventual allocation of responsibilities could emerge through top-down requirements such as technical standards or through natural evolution of the AI ecosystem. AI infrastructure providers may be incentivized to build more guardrails and compliance tools into their offerings. Since downstream developers prefer options with lower compliance overhead, the ease of compliance would become a dimension of competition between foundation model developers, with responsibilities naturally shifting toward the upstream.

Open-Source Models

A critical aspect of AI governance involves addressing the dynamics of open-source models and their ecosystems. AI infrastructure providers typically offer their models through an application programming interface (API) or an open-source format. The API model allows for control over and visibility into downstream use, along with the possibility of directly charging for API use. In contrast, under the open-source model, providers make their source code and sometimes training data available for download. While some firms monetize their work through support and consulting services, others focus on building a community of developers who are familiar with the open-source technology stack and whose contributions could be incorporated into future product releases.

From a national economy perspective, promoting open-source technology is instrumental to accelerating China's broader technological advancement by democratizing access to foundational AI models. Open-source pretrained models and fine-tuning algorithms create a shared knowledge base, enabling downstream entities to adapt and customize models to their specific needs. This approach helps avoid wasteful efforts to train similar large models and lowers entry barriers for firms that lack the means to develop proprietary models from the ground up. The Chinese government recognizes the positive externalities of open-source models. For example, the Beijing Academy of Artificial Intelligence (BAAI) embarked on a mission with government funding to develop open-source LLMs that permit commercial use.

However, a notable gap in China’s generative AI regulations is the lack of specific guidance for open-source providers, which leads to ambiguity. The Interim Measures do not distinguish between open-source and API model providers. Imposing the same responsibilities on open-source and API providers could inadvertently hamper innovation. Open-source providers generally have limited insight into how their models are utilized in downstream applications and therefore cannot be held primarily responsible. The open-source community, comprising independent researchers, hobbyists, and students, is often motivated to contribute by personal passion or reputation building and may not possess the resources to adhere to stringent compliance requirements. While it is reasonable to require noncorporate open-source developers to provide essential documentation (e.g., descriptions of training data), imposing obligations such as conformity assessment, ongoing maintenance, or algorithm registration could be excessively burdensome.

Conclusion

China's approach to regulating general-purpose AI strikes a balance between the aims of fostering innovation and ensuring control. This approach mandates alignment with the Party’s interests while addressing universal AI challenges like safety, fairness, transparency, and accountability. The country is poised to adopt a risk-based framework, either rolling out tailored regulatory requirements or reinforcing existing rules in a tailored way. Like other jurisdictions, China is exploring effective ways to distribute responsibilities across the AI value chain and cultivate a robust open-source community.

Notably, China has integrated substantial support for innovation into its regulatory framework. The government is committed to nimble regulation and seeks to employ top-down coordination to meet common AI development needs, such as access to high-quality training data and computing power. The court decision to grant copyright to AI-generated outputs is a testament to this bias toward innovation.

As the AI industry evolves and business dynamics become more defined, Chinese policymakers are likely to refine the regulatory details in areas currently marked by ambiguity. However, it is important to remember the policy effects of decisions regarding AI governance made by any country, including China, are not confined to national boundaries. In many cases, domestic regulations carry extraterritorial effects. In addition, combatting the proliferation of AI capabilities to malicious actors, ensuring the alignment of AI systems with human values, and achieving technological interoperability will require cross-border, multilateral cooperation.

In short, the evolving regulatory landscape in China will shape and will be shaped by global discourse and developments in AI governance. The second paper in this series will address these broader international issues and their implications for China's AI pursuits.

No comments:

Post a Comment