SÉBASTIEN ROBLIN

The night of January 27, U.S. military personnel were sleeping in a tent serving as temporary living quarters at a forward base called Tower 22 (located near the Jordan-Iraq-Syria border) when a buzzing kamikaze drone swooped down and exploded. The blast killed three U.S. Army Reservists from the Georgia-based 718th Engineer Company and injured over 40 more troops. Eight were evacuated abroad for treatment, and are thankfully in stable condition.

Established in 2015, Tower 22 is one of many outposts set up by the Pentagon throughout the Middle East to support anti-ISIS operations. Along with several other nearby bases, Tower 22 has extensive aviation facilities and hosts logistics, security, and engineering units that support a key U.S. special forces base just 12 miles away across the border in at-Tanf, Syria.

As Tower 22 reportedly housed 350 U.S. soldiers and airmen, roughly one-tenth of its personnel were killed or wounded by the drone attack.

Since the onset of the Israel-Hamas war on October 7, 2023, there have already been around 165 attacks mounted on various U.S. bases in Iraq and Syria by Iran-backed militant groups collectively dubbed the ‘Axis of Resistance’. Thanks to stout air defenses and luck, none had yet proven fatal, but they had already caused 170 injuries.

This content is imported from x. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.

This was the first attack on U.S. forces since October 7 to have lethal results (though two Navy SEALs were also lost at sea during an operation intercepting arms smugglers in the Red Sea).

On eight separate occasions, U.S. warplanes conducted retaliatory or preemptive strikes against groups staging for attacks, and killed senior member of an Iran-back militia in Iraq. But these groups were undeterred, and it seemed only a matter of time before one of the attackers would get lucky and find a weak spot.

A photo from December 2018 featuring sergeants from the 77th and 300th Sustainment Brigades at Tower 22 shows the base’s use of tent-based facilities.

New reporting by the Wall Street Journal suggests that the source of the fatal gap in defenses—whether by design or sheer luck—was the fact that the low-flying kamikaze drone approached at the same time a U.S. surveillancedrone was expected to land, and was thus not engaged by air defenses.

It resembles, in a way, Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor—the attack was spotted by U.S. radars, but dismissed by operators as likely being a formation of B-17s that were scheduled to land in Hawaii at the same time. And of course, attacking at night reduces opportunities to visually distinguish a hostile drone from a friendly one.

AN/TPS-75 PESA phased array radar being optimized by the 84th Radar Evaluation Squadron at Camp Rilea, Oregon--typically transported by two 5-ton trucks and adaptable to various roles, including ballistic missile defense.

Tower 22 is known to have been overwatched by an AN/TPS-75 PESA-type phased array radar typically used by the U.S. Air Force for flight control and early warning, and reportedly did have counter-drone defenses. But the nature of its kinetic defenses is unclear. Elements may included the automatically guided Guardian C-RAM autocannons and Stinger missiles, either dismounted or mounted on Avenger Humvee systems.

Stingers and C-RAM are both counters against drones. C-RAM can gun down incoming mortar rounds and artillery rockets as well, which are also common forms of attack. It’s also likely that some counter-UAS systems (like portable drone jammers or Coyote interceptor drones) were present at the base—but, again, not used due to the failure to identify the approaching threat.

The base was not covered by one of the U.S.’s few and highly expensive Patriot air defense missile batteries, which—due to their high price per shot ($3-4 million per missile)—are not considered ideal counters to threats from cheaper drones. However, Patriots are preferred counters against ballistic missiles (which Iran has directly launched at U.S. bases in the Middle East on at least two occasions), and there have been requests for Patriot coverage of U.S. bases in Jordan.

Some rumors suggest that the drone was launched from Imam Ali base near Abu Kamal in southern Syria, which is used by the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps and its allied militias.

However, a group called the “Islamic Resistance of Iraq” has claimed responsibility for attacks on 3 U.S. bases, and has released a video purporting to show the rocket-assisted takeoff of the killer drone. As this is an umbrella organization for several Iranian-backed Shia militias, the claim diffuses responsibility, leaving the exact perpetrators unclear, though suspicion reportedly is falling particularly on the group Kataib Hezbollah. Iran has denied launching the attack.

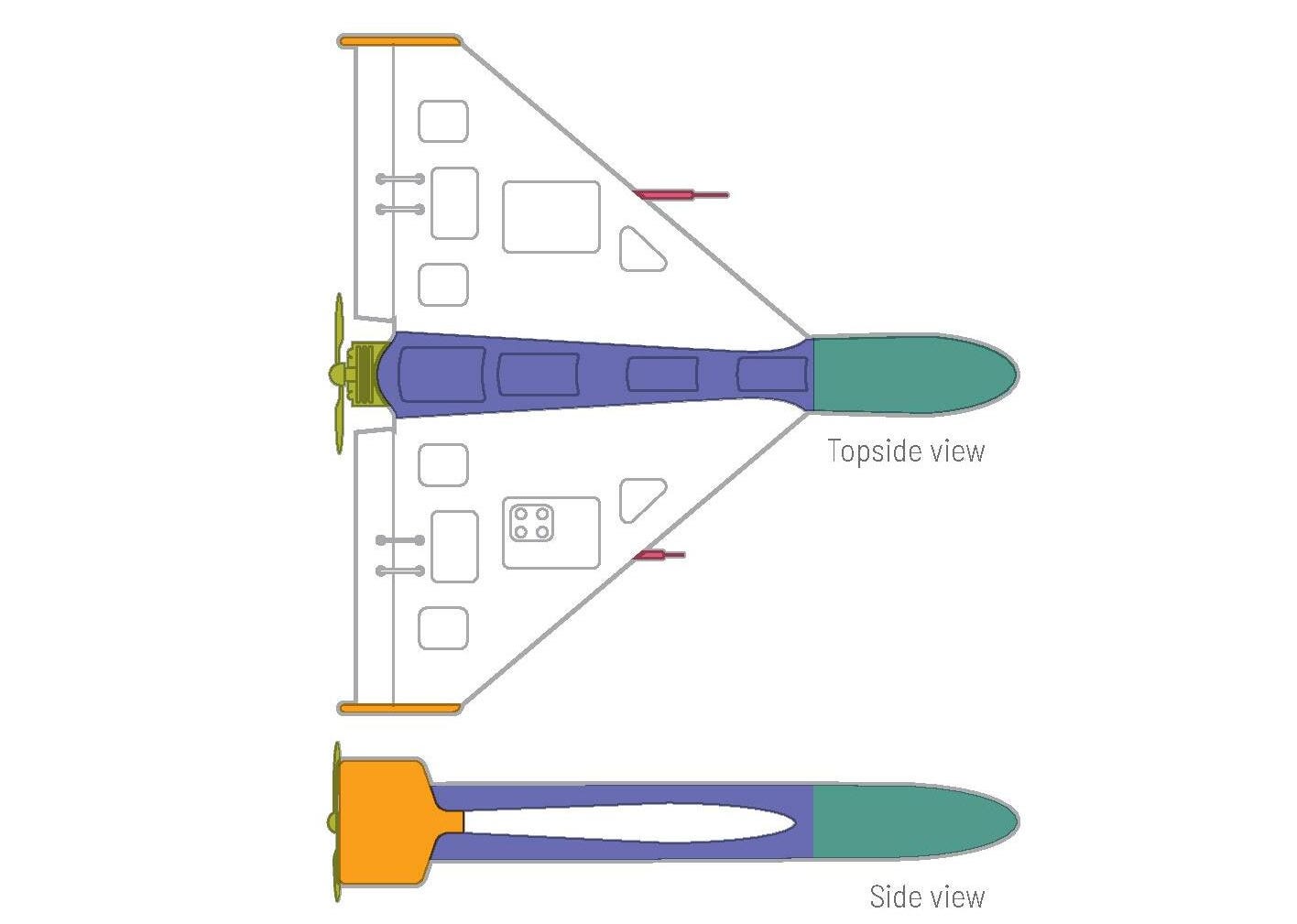

The type of kamikaze drone used remains unreported for now. Iran is known to have developed many purpose-designed kamikaze drones like the Shahed-136 and -131 (which often use rocket boosters for launch), and to have transferred both parts for assembly and know-how to regional actors including Hamas, Hezbollah, and Houthi rebels in Yemen. They have also been shared with Russia’s military for use in sustained large-scale attacks on Ukrainian cities.

Regarding the attack on Tower 22, it remains to be confirmed whether the drone was of Iranian lineage or improvised locally. The rocket-boosted takeoff and description of the drone as relatively ‘large’ may point to a platform like Iran’s Shahed-136.

Overall, the Tower 22 attack reinforces the growing deadly threat posed by drones—even those deployed by non-state actors—and the need to systematically deploy anti-drone capabilities everywhere. To be fair, it’s likely that such defenses were present at a base Tower 22’s size, but failed to engage due to an identify-friend-or-foe error. No defense is perfect, and given enough chances, attackers are likely to get lucky at least once.

Why are U.S. troops at Tower 22, and how may Washington respond?

While the anti-ISIS coalition succeeded in driving ISIS from the urban strongholds it occupied at the height of its power, the terrorist group has managed to moderately resurge in areas where anti-ISIS coalition forces have withdrawn. For this reason, the U.S. and its coalition partners have maintained some forces in the Middle East to sustain pressure on the group.

Special ops Black Hawk helicopter carrying Maj. Gen. James Jarrard arrives at the landing zone of the U.S. Special Forces base in at-Tanf, Syria--greeted by Humvee and MRAP vehicles of the 5th Special Forces Group’s Bravo 5310 detachment in November 2017.

However, over the years, these outposts like Tower 22 and at-Tanf have become punching bags for various Iranian-armed resistance groups, which dub themselves the ‘Axis of Resistance.’ These non-state actors provide cover for Iran, which seeks to displace the U.S. presence across the Middle East in favor of its own armed proxies like Iraq’s Popular Mobilization Forces and Houthi rebels controlling much of western Yemen.

Two major U.S. bases (situated in regions of Syria and controlled by Kurdish separatists) are furthermore irksome to the Iran-backed Syrian regime of dictator Bashar al-Assad, as they prevent the re-consolidation of his authority across the country.

Iran’s regional proxies, however, are taking advantage of surging enthusiasm for attacks on U.S. forces due to Israel’s bloody war against Hamas in Gaza. And the U.S.’s regional allies, in turn, are reluctant to openly support the U.S. for fear of being perceived as tacitly supporting Israel. This makes for opportune timing to attack U.S. troops in support of Iran’s agenda while ostensibly showing support for the Palestinian cause. The mere act of attacking Americans (effectually or otherwise), and getting hit back by U.S. forces, pumps up street cred in the region and makes deterring these groups difficult.

The Biden administration has been keen not to reward groups seeking to provoke an escalated response that could lead to a broader regional war—one which could suck U.S. forces back into the Middle East and away from arguably more important foreign policy priorities in Europe and the Pacific.

However, the U.S. will undoubtedly be compelled to mount lethal, targeted attacks against the group it deems responsible for the Tower 22 incident. This may require some discerning intelligence work, as groups waging such attacks often diffuse responsibility in hopes of diverting retribution away from themselves. To what extent the retaliation will fall on groups in Iran or Syria, and how broad the retaliation will be beyond the attack’s direct perpetrators, will need determining.

Broadly, the combination of the Israel-Hamas war and Iran and its proxies are frustrating the U.S.’s general desire to maintain a smaller, lower-profile footprint in the Middle East and focus security efforts elsewhere. This forces the U.S. to chose between unpleasant choices: either withdrawing forces to Iran and ISIS’s benefit, reinforcing the U.S. presence and aggressively retaliating at risk of larger war in the Middle East, or trying to sustain the present course weathering constant attacks that—through sheer frequency—are bound to cause more casualties eventually.

No comments:

Post a Comment