Marc Lanteigne

With the Arctic finding itself under ever greater global scrutiny due to climate change, and opening up to increased economic activities, from shipping to mining to fishing, the question of whether great power competition is spilling over into the far north has assumed greater importance. One aspect of this attention has been the idea of a probable, and perhaps even inevitable, Arctic pact between China and Russia, one based on mutual northern interests and shared mistrust of the West.

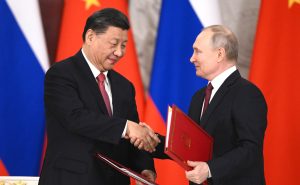

At first glance, there is much evidence to support this view, especially with Beijing declining to condemn the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and instead adopting a nebulous policy of neutrality toward the conflict. China and Russia are both pushing back against what they perceive as NATO militarism and expansionism in the Arctic. The Polar Silk Road, which the two states began to jointly develop after 2017, was meant to further enhance Sino-Russian boreal cooperation, centering on the Northern Sea Route connecting Asia and Europe via the waters abutting Siberia.

These points of collaboration are now more commonly viewed as signals that a deeper Arctic pact is forming between the two powers. One recent example is a report, published earlier this month by American intelligence firm Strider Technologies, which argued that China is rapidly increasing its economic presence in the Russian Arctic and that Moscow has opened the door to Chinese interests in Siberia and Russia’s Far East. This would suggest the powers are now openly seeking to counterbalance the West in the Arctic in light of NATO’s expansion to include Finland and likely Sweden. In short, there is the conclusion that the Sino-Russian “no limits” partnership – declared in February 2022, on the eve of the invasion of Ukraine – is allegedly thriving in the Arctic.

A closer look at the pattern of Sino-Russian cooperation in the Arctic over the past decade, however, reveals much more ambivalence, especially on Beijing’s part. There are concerns within both governments as to each other’s future intentions in the Arctic. Far from pursuing an “unlimited” partnership, Beijing has instead selectively engaged Russia in the Arctic, in areas that reflect China’s own interests, such as increased science diplomacy, and has agreed to purchase Russian oil and gas (at discounted rates).

As for overall shipping, Chinese firms have been reluctant to use the Northern Sea Route since 2022 due to concerns about facing Western sanctions for providing economic assistance to Russia. Additionally, the Hong Kong-registered vessel Newnew Polar Bear was placed under an uncomfortable spotlight after being implicated in undersea cable cuts in the Gulf of Finland last October.

China’s stance on oil and gas development in the Russian Arctic has also been sporadic, with Beijing remaining tepid on Russian interests in co-developing the Power of Siberia 2 natural gas pipeline. Chinese energy firms have made only infrequent protests over Western sanctions on Russia.

The Strider report highlighted a considerable uptick in Chinese firms registering to operate in the Russian Arctic as a sign of deepening bilateral cooperation in the region. Yet this leads to the question of whether these figures reflect an immanent increase in joint China-backed Russian Arctic projects, or merely a window of opportunity for Chinese interests to jockey for position, given the spaces vacated by European firms decamping from Russian partnerships. What remains to be seen is whether the potential impact of the growing number of Chinese companies in the Arctic will represent any significant economic power shift, given ongoing Russian sensitivity to the economic sovereignty of its Arctic lands, and the uneven track record of previous joint Polar Silk Road projects in Siberia.

One notable example is the long-planned Belkomur rail link in western Siberia, which was touted as a potential Sino-Russian investment in a vital land link for Eurasian trade. The project remains in bureaucratic limbo, with ongoing questions about its economic viability.

Moreover, China originally perceived the Polar Silk Road as eventually linking Chinese interests with the whole of the Arctic, with plans ranging from mining in Canada and Greenland, to rail links in the Nordic region, to natural gas development in Alaska. Few of these projects are likely to move forward. Now Beijing must deal with Russia as its only viable economic outlet to the Far North, a situation the Chinese government did not anticipate when the Polar Silk Road was first established.

Much discussion of closer Sino-Russian Arctic ties ignores the fact that Moscow is seeking to further diversify its Arctic partners beyond China, by including India and countries in the Gulf Region. With Russian participation in the Arctic Council reduced since March 2022, Moscow has made little secret of its interest in looking for additional Arctic partners elsewhere.

Last year, Russia called for a BRICS science station to be established in Pyramiden, in Norway’s Svalbard archipelago, which would allow not only China but also other members of the group such as Brazil and India to participate. This came at a time when the BRICS are in the process of expanding their membership, with countries such as Egypt, Iran, and the United Arab Emirates already signed on (and the UAE has recently given many indications that it is seeking to expand its own Arctic interests). While China will remain an integral player in Moscow’s Arctic planning, it is evident that the Russian government is counting on the creation of a wider alternative Arctic regime.

Despite lofty declarations of mutual interests in the Arctic, there have been significant cracks in this regional relationship. These include ongoing concerns about demographic stresses between Russia’s depopulated Arctic territories and adjacent Chinese provinces. In addition, in 2020 a Russian Arctic researcher was accused of spying for Beijing, and overall there has been little movement beyond rhetoric on further joint research initiatives between the two states.

Another telling sign of trouble was the release of an official standard Chinese map in August last year, which designated an island shared by the two powers, Bolshoi Ussuriysky (Heixiazi Island in Chinese), as wholly belonging to China. The Chinese Ministry of Natural Resources had also decreed in February 2023 that its own maps of the Russian Far East be changed to use traditional Chinese names of Russian cities like Vladivostok. These moves must also be considered when discussing the robustness of Sino-Russian Arctic cooperation.

The underlying question is whether there is a threshold degree of trust between China and Russia to allow for a deepening of Arctic cooperation. Both countries have engaged in joint military operations in and near the Arctic, such as off the coast of Alaska in August of last year, but it remains unclear as to whether these displays have served any purpose beyond a show of unity versus the West. The signing of a bilateral coast guard agreement in Murmansk, near the Finnish border, was symbolic, but there has been little sign that Russia will significantly yield its coveted Arctic maritime space to Chinese vessels.

The Russian government remains concerned about China’s longer-term goals in the region, especially as the power gap between the two states continues to widen. Beijing worries about being too dependent upon Russia, especially since the future of that country remains cloudy, at best. The 1969 Sino-Soviet border war has likely not been forgotten by either power, and remains a cautionary tale for both states about the dangers of, to use the Maoist-era phrase, “leaning to one side” too much.

While the far-northern strategies of Beijing and Moscow need to be carefully analyzed, presuming that the two states are in lockstep with their regional policies creates a distorted strategic picture at a time when clarity about Arctic security is desperately needed.

No comments:

Post a Comment