MICHAEL NATALE

"Peruse again and again the campaigns of Alexander, Hannibal, Caesar, Gustavus Adolphus, Turenne, Eugene, and Frederick. Model yourself upon them. This is the only means of becoming a great captain, and of acquiring the secret of the art of war."

This was the advice given to officers by Napoleon Bonaparte, whose name would soon join, if not supplant, many of the revered military leaders he listed.

More than two centuries later, the public still has a fascination with Napoleon, as evidenced by the box office success of Ridley Scott's epic new film starring Joaquin Phoenix as the titular general. But Napoleon is hardly the only military leader to endure in the public consciousness. Alexander the Great is expected to get the big-screen treatment once again, this time at the hands of 300 director Zack Snyder. And even Ulysses S. Grant, whose reputation (particularly as U.S. President) was maligned over the 20th century by lost cause revisionism, is now seeing a historical reevaluation via new biographical books.

That's likely because, while the weapons of war have evolved drastically over the centuries, we can still learn so much from the tactics of major military leaders of the past—and continue to reckon with the ethics of some of their choices.

The decisions they made on horseback in battle, or from behind a desk an ocean away, led to decisive victories that shaped the course of human history. But the unintended collateral damage of their decisions also impacted the world we live in today.

Victories and defeats, liberation and oppression, are as much the story of military leaders as they are the armies they commanded. After all, as Alexander the Great once said:

"An army of sheep led by a lion is better than an army of lions led by a sheep."

1. Alexander the Great (356 - 323 B.C.)

As the centuries endure, it's easy to see much of history resigned to the fate of Percy Bysshe Shelley's Ozymandias: figures of antiquity fade from memory, left behind in the march of time.

But more than two millennia after his death, that fate has not befallen the legacy of Alexander the Great, whose life and leadership tactics are still studied to this day.

Alexander's ascent to power was not an easy one. Though he was the son of King Philip II and Queen Olympia of Macedon, and he was educated by no less than Aristotle, Alexander's future seemed uncertain when a Macedonian noble named Pausanias killed King Phillip at a festival celebrating the wedding of Alexander's sister.

The 19-year-old prince had to rally support from the Macedonian army, who declared him feudal king and, as Biography notes, "proceeded to help him murder other potential heirs to the throne."

After persuading the Greek city-states to give him control of the Corinthian League, Alexander the Great led a series of campaigns and conquests that often employed a "hammer and anvil" strategy of phalanxes to secure decisive victories, and expand his empire across Egypt, eastern Iran, and Northern India. With his defeat of the Persian army at the Battle of Guagamela, he was declared "King of Babylon, King of Asia, King of the Four Quarters of the World."

Alexander died of malaria at the age of 32 in Babylon (modern-day Iraq). With his death came the collapse of his vast empire, and its internal nations all grasped for power to fill the vacuum.

Reflecting on this in the 2nd century A.D., Marcus Aurelius would wryly note, "Alexander the Great and his mule driver both died and the same thing happened to both. They were absorbed alike into the life force of the world, or dissolved alike into atoms."

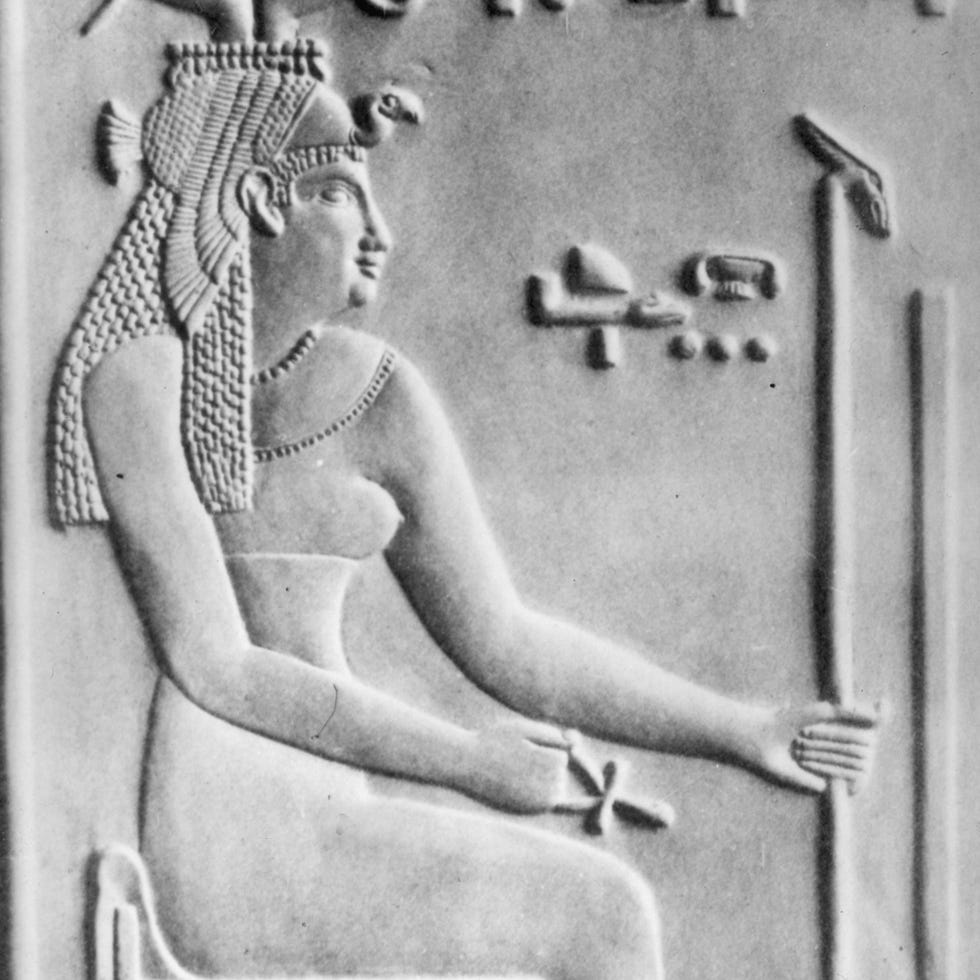

2. Cleopatra (69 - 30 B.C.)

These days, Cleopatra is often portrayed as glamorous, and simply in proximity to "great men" like Julius Caesar and Marc Antony. She's summed up, as Shakespeare's Enobarbus would say, with the idea that "Age cannot wither her, nor custom stale/Her infinite variety."

But Cleopatra VII was far more than a romantic interest in the annals of history. As Biography notes, the Egyptian Queen was, in fact, "an incredibly intelligent leader who excelled at politics, diplomacy, communications, and building strategic allegiances."

After the death of her father, Ptolemy XII, in 51 B.C., Cleopatra and her younger brother, Ptolemy XIII, came into conflict over who should rule Egypt. Cleopatra fled to Syria, gathered an army under her command, and returned to Egypt in 48 B.C. to face her brother's forces.

While we often romanticize a lone leader charging their small army against a greater force, Cleopatra understood that alliances were vital to not just victory, but post-war stability. An alliance (and, yes, romance) with Caesar helped secure Cleopatra her throne. A later bond with Marc Antony after Caesar's assassination would, however, prove less successful. Their combined loss to Octavian led to both Antony and Cleopatra's suicides.

3. Genghis Khan (1162 - 1227)

"No other commander in history has been more acutely aware of the fundamental importance of seizing and maintaining the initiative of always attacking, even when the strategic mission was defensive" wrote Captain Dana J. H. Pittard, U.S. Army, in the pages of Military Review, July 1986.

Captain Pittard's article is one of many works chronicling, and critiquing, the life and legacy of Genghis Khan. These include the oldest surviving work in the Mongolian language, which was written after the so-called "flail of God" had died.

Much of what we know about Genghis Khan comes from the vastness of his lineage and his empire, and the accounts of those who survived his deadly raids.

You know about the brutality of the man born Temujin in around 1162, which included boiling Taichi'ut chiefs alive, and ordering the slaughter of any Tatar man more than 3 feet tall. Most infamous, perhaps, is the invasion of the Khwarazmian Empire. As Biography notes of the slaughter, "no living thing was spared, including small domestic animals and livestock," and the "skulls of men, women, and children were piled in large, pyramidal mounds."

But Khan's dominance owes as much to strategic mastery as it does to shocking violence. Khan "employed an extensive spy network and was quick to adopt new technologies from his enemies," which included "a sophisticated signaling system of smoke and burning torches." And his well-equipped cavalrymen could steer their horses with just their legs, keeping arms free to fire arrows at the opposing hordes.

Khan died in 1227, leaving behind the largest empire in the world, until the British Empire arised centuries later.

4. Joan of Arc (1412 - 1431)

"...She was a rock of convictions in a time when men believed in nothing and scoffed at all things..." - Mark Twain, Joan of Arc

The English tried to paint her as a heretic. Nearly 500 years later, the Catholic Church declared her a saint.

Jeanne D'Arc, or Joan of Arc, led the French army to victory over the English at Orleans, at only 18 years of age. Each small victory of her campaign in the early summer of 1429 was met with the Armagnacs around her suggesting they stop and take stock, but Joan pushed her army ever onward, achieving what many had deemed impossible. "By mid-June," Biography says, "...the French had routed the English and, in doing so, their perceived invincibility as well."

The key to Joan of Arc's victory over England during the Hundred Years War was the same force that brought the poor farmer's daughter from Doremy to the court of Charles VII: her unflappable faith and confidence in her convictions.

From a young age, Joan was guided by visions of "St. Michael and St. Catherine designating her as the savior of France." Feeling, and declaring, that she had a mandate from heaven allowed Joan to charge ever-forward where others would not have dared. But this religious conviction also led to her conviction for heresy when she was eventually captured by the English. On May 29, 1431, an English tribunal declared Joan guilty, and on May 30, she was burned at the stake.

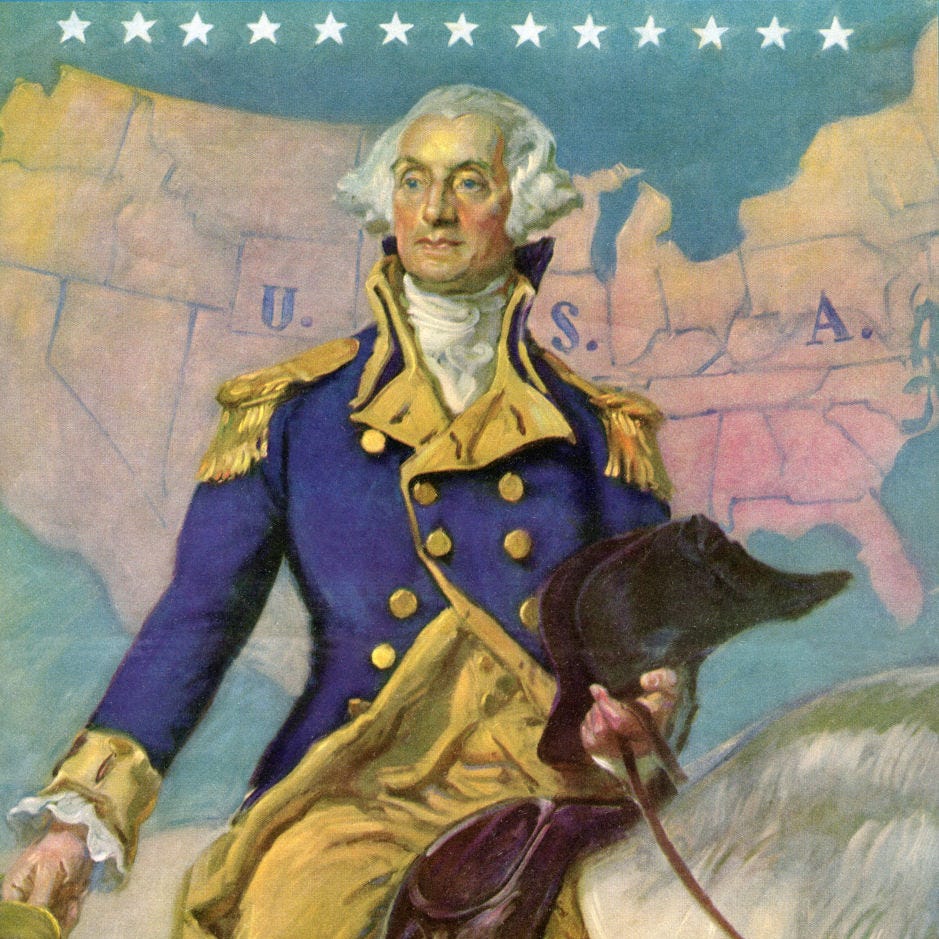

5. George Washington (1732 - 1799)

In the aftermath of Lexington and Concord, it was clear that the Second Continental Congress would need to be ready for war. George Washington, a planation owner and veteran of British General Edward Braddock's army in Virginia, was seen as the right choice because, per Biography, "...he had the prestige, military experience and charisma for the job and he had been advising Congress for months."

Except, of course, Washington's military experience wasn't really suited to the battles ahead. Biography continues:

"Washington's training and experience were primarily in frontier warfare involving small numbers of soldiers. He wasn't trained in the open-field style of battle practiced by the commanding British generals. He also had no practical experience maneuvering large formations of infantry, commanding cavalry or artillery, or maintaining the flow of supplies for thousands of men in the field."

But as it turned out, it was to Washington's advantage that he wasn't trained in the same manner as his opponents. Washington was able to adapt and fight the war as it was, where the British merely fought as they always had.

"Americans began to believe that they could meet their objective of independence without defeating the British army." Meanwhile, the British leadership "...didn't realize that capturing cities like Philadelphia and New York would not unseat colonial power. The Congress would just pack up and meet elsewhere."

The ability to assess the conflict at hand, as well as assemble a reliable team of allies like Marquis de Lafayette and Alexander Hamilton, would serve him well not just in winning the war, but in running the country as the United States of America's first President.

6. Napoleon Bonaparte (1769 - 1821)

As a young Corsican boy at the military college of Brienne, Napoleon Bonaparte looked to conquering figures of antiquity like Alexander the Great for inspiration. And through a combination of tenacity, a brilliant tactical mind, and some remarkable timing, Napoleon actually did manage to reach the heights of those towering figures of yore, becoming one of the most pivotal military leaders of the 2nd millennium.

Napoleon never would have become Emperor of France, strangely, were it not for the French Revolution. Having risen in the ranks in the French military, Napoleon initially allied himself with the Jacobins, a far-left movement during the Revolution. After Robespierre's Reign of Terror and the implementation of the Directory, Napoleon was given command of the Army of Italy, which Biography describes as "just 30,000 strong, disgruntled, and underfed," and used this force to win major victories against Austria and expand the French Empire thanks to his cunning and precise command.

Returning to France, Napoleon took part in the Coup of 18 Brumaire, a bloodless coup that eventually led to his absolute rule over France. Shortly thereafter, Napoleon secured a narrow victory in the Battle of Marengo, propaganda of the time elevated it to a glorious triumph, solidifying Napoleon's hold on power.

This combination of strategic victories and aggressive messaging worked well for Napoleon, right up to the point where it didn't anymore. His disastrous invasion of Russia was a major miscalculation, resulting in his exile. And though he returned briefly to power, a humiliating defeat at Waterloo resulted in a second and final exile.

7. Ulysses S. Grant (1822 - 1885)

Would you believe America's first-ever four-star General once said "a military life had no charms for me"?

Ulysses S. Grant wasn't planning on becoming President. He wasn't planning on a military career. Heck, he wasn't even really named Ulysses S. Grant! When Hiram Ulysses Grant was enrolled at West Point, there was a clerical error, and he chose to simply change his name to fit the flub.

During the Mexican-America War, Grant served under both General Zachary Taylor and General Winfield Scott, learning from both before bravely leading his own company. But he also "developed strong feelings that the war was wrong, and that it was being waged only to increase America's territory for the spread of slavery." Grant, like his father before him, opposed slavery, but his wife and her family were slave-holders. Grant himself did own a man named William Jones for roughly a year before freeing him.

He would try to pursue a civilian life after the Mexican-American War, but the outbreak of the Civil War brought him back to the battlefield. Early victories for Grant included the capture of both Fort Henry and Fort Donelson, for which he earned the nickname "Unconditional Surrender Grant."

As Grant raised through the ranks of leadership, he "saw the military objectives of the Civil War differently than most of his predecessors, who believed that capturing territory was most important to winning the war," Biography writes.

Grant instead feverishly pursued General Robert E. Lee's Army of North Virginia from March 1864 until April 1865. On April 9, 1865, Grant accepted Lee's surrender. Understanding the need for reconciliation after the war, Grant allowed Lee's soldiers "to keep their horses and return to their homes, taking none of them as prisoners of war."

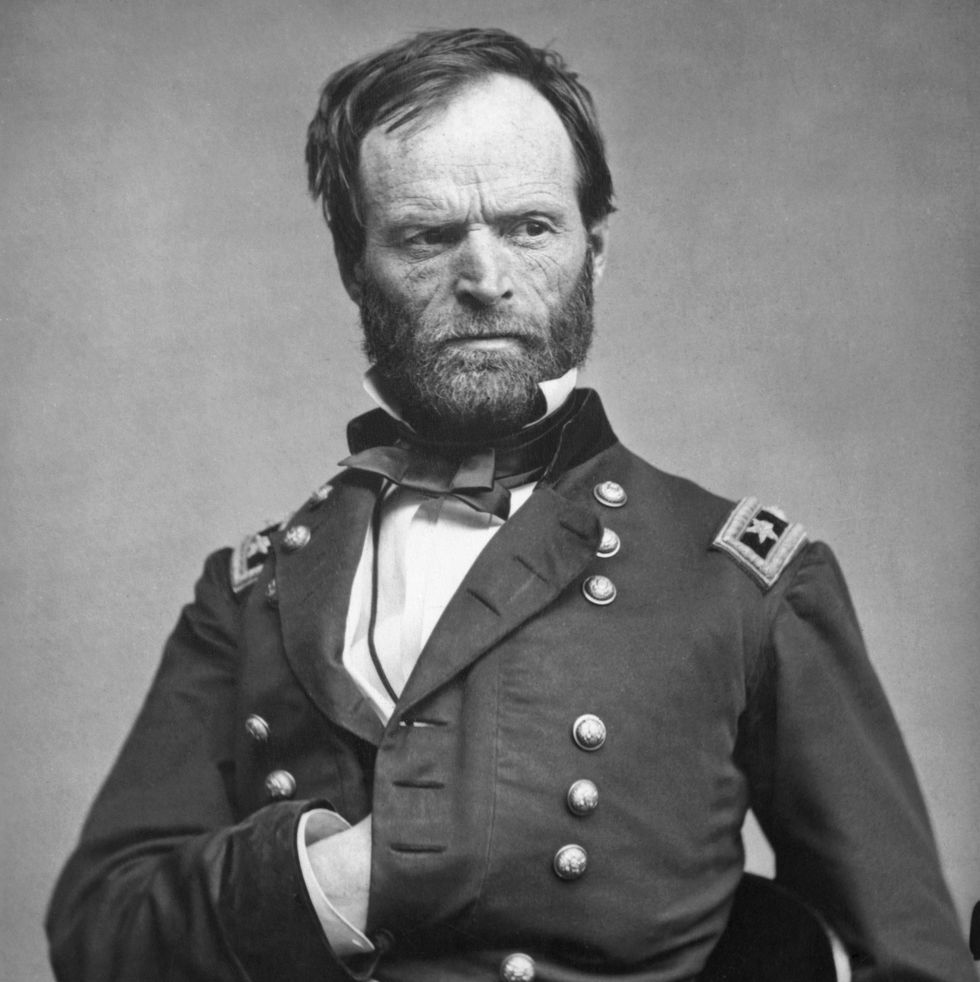

8. William Tecumseh Sherman (1820 - 1891)

William Tecumseh Sherman: Decisive leader or destructive leviathan? Where you land on that might depend on what side you land on the Mason-Dixon line, or at the very least, how you feel about the second act of Gone With The Wind.

It's fair to say Sherman was a complicated figure. He supported the Union, but Biography notes that he was personally "conservative on slavery." His middle name was chosen to honor a Shawnee Chief, and he spoke out against the mistreatment of indigenous reservations by the government, but as general commander of the U.S. Army, Sherman oversaw "total destruction of the warring tribes."

Sherman is often credited with implementing a "total war" tactic often referred to as "Sherman's March to the Sea," though some contemporary historians dispute that characterization. What began with the destruction of railways in Alabama grew into the burning of Atlanta (depicted apocalyptically in Gone with the Wind) and his "60,000 men" creating a "60-mile-wide path of total destruction."

As was the consensus in the 19th century, Biography says, "Sherman understood that to win the war and save the Union, his Army would have to break the South's will to fight." But the aftermath of the war, particularly the blows dealt to the Reconstruction effort by Presidents Andrew Johnson and Rutherford B. Hayes, would later cause some to question the necessity of the depths of Sherman's decimation, particularly amongst advocates of the pseudo-historical Lost Cause Revisionism.

9. Menelik II (1844 - 1913)

If the portion of New Imperialism colloquially referred to as the "Scramble for Africa" is mentioned at all in the textbooks of American or most European schools, it is almost exclusively to reckon with (and depending on the educator, attempt to excuse) the horrors wrought upon the continent by the British Empire and the monstrous King Leopold of Belgium.

But there is one remarkable story from this tumultuous time that countries with colonial roots tend to gloss over—a battle whose victory is still celebrated annually in Ethiopia to this day. The Battle of Adwa, where invading Italian forces were roundly defeated by an Ethiopian army, commanded by Emperor Menelik II.

On May 2, 1889, Italy and Ethiopia signed the Treaty of Wichale. Except, the countries actually signed two different agreements:

"Article XVII in the Italian version of the treaty stated that Menelik had agreed to Ethiopia becoming a protectorate of Italy, while in the Amharic version the country's independence was maintained."

When Italy tried to enforce their claim, Menelik pushed back. "My kingdom is an independent kingdom," he said, "...and I seek no one's protection," according to Biography.

Italy tried to take the nation by force, but though Ethiopia had been ravaged by plague and famine the previous year, Menelik managed to rally troops with the plea, "Today, you who are strong, give me your strength, and you who are weak, help me with your prayer."

On March 1, 1896, the Battle of Adwa saw Menelik's 100,000 Ethiopian soldiers beat back the Italians, who eventually signed the Peace Treaty of Addis Ababa. Through his tenacity, Menelik became "the first African ruler to successfully counter a colonial invasion."

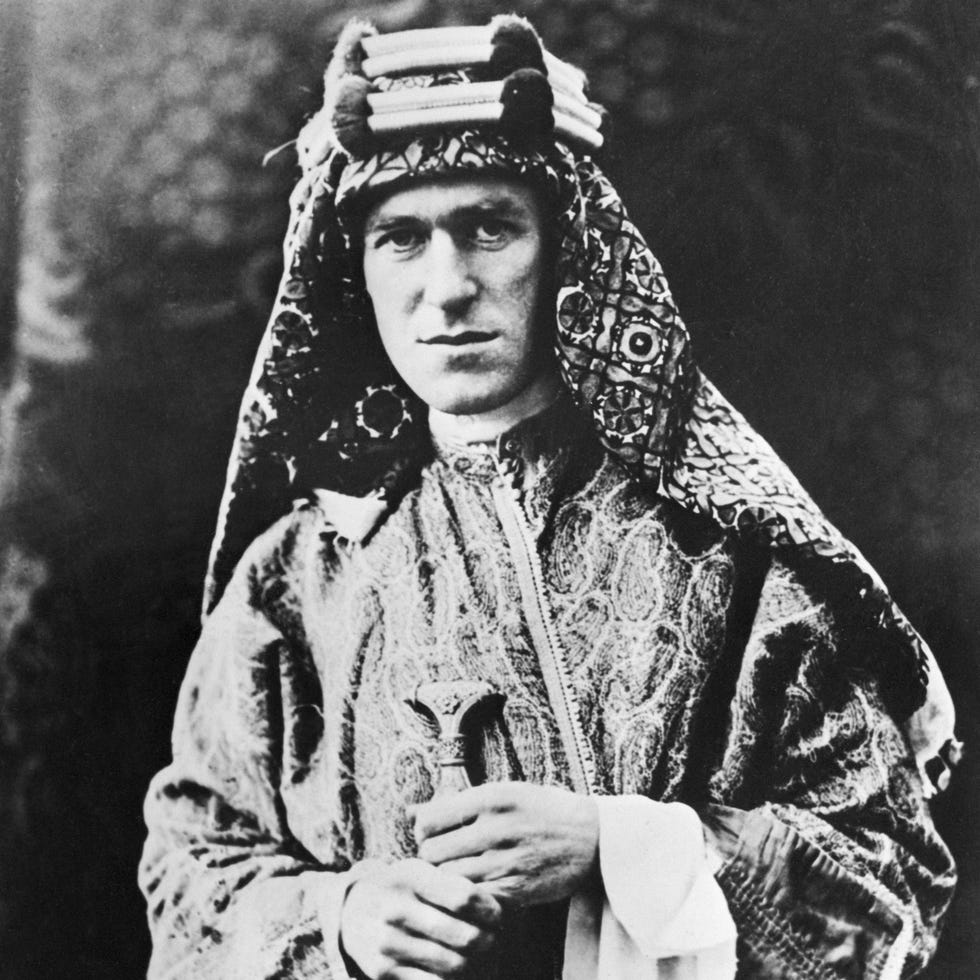

10. T.E. Lawrence (1888 - 1935)

Few figures of the British Empire are as complex, controversial, and confounding as T.E. Lawrence. Known for his role in the Arab Revolt against the Ottoman Empire, a role that (some suggest inadvertently) helped advance British colonial interests in the region, the question of just who the man called Lawrence of Arabia was hasn't fully been answered, even a century later.

Some called his famed memoirs Seven Pillars of Wisdom fabulist and exaggerated. Others posit that Lawrence's supposed importance was exaggerated by the British government, who needed a positive figure in World War I to contrast all the devastation on the Western Front. And many wonder just how much Lawrence knew about the Sykes-Picot Agreement that would carve up, for European powers, the very region he was fighting to ostensibly liberate.

We know that Thomas Edward Lawrence developed an appreciation for what was then called Arab affairs during his time working for the British Museum as a junior archeologist. With the outbreak of WWI, Lawrence was recruited by British Intelligence.

"Lawrence joined Amir Faisal al Husayn's revolt against the Turks as political liaison officer, leading a guerilla campaign that harassed the Turks behind their lines," Biography notes. "After a major victory at Aqaba—a port city on the southern coast of what is now Jordan—Lawrence's forces supported British General Allenby's campaign to capture Jerusalem."

Undeniably, something changed in Lawrence after his capture and torture in Dar'a in 1917. While it’s unclear how much he knew of the British intentions toward the Arab people before the end of the war, he was vocal in his support for Arab independence afterward, declining the Distinguished Service Order and the Order of Bath awarded to him by King George V.

11. George S. Patton (1885 - 1945)

The life of George S. Patton would, were it not heavily documented and chronicled in countless history books, seem like the stuff of fiction. A West Point-educated Olympic athlete who first proved himself on the field of battle by personally shooting one of Pancho Villa's captains, who revolutionized tank warfare in World War I, and achieved victories in Italy and France in World War II. Oh, and he also wrote poetry on the side.

"To this day," Biography writes, "Patton is considered one of the most successful field commanders in U.S history."

During World War I, Patton saw the instrumental role tanks played in the Battle of Cambrai, and set about educating himself to become "one of the leading experts in tank warfare." His establishment of an American tank school in Bourg, France, and leadership of the tank brigade, earned him the the Distinguished Service Medal.

During World War II, Patton further solidified his reputation. "In 1943, he used daring assault and defense tactics to lead the 7th U.S. army to victory at the invasion of Sicily," according to Biography. He later commanded the 3rd U.S. Army, which "swept across France, capturing town after town."

Patton earned the nickname "Old Blood and Guts" for his ruthlessness, not only on the battlefield, but beyond it. Patton earned infamy for his many "slapping incidents," some of which involved soldiers afflicted with shell-shock (now called PTSD). One of Patton's poems, "Peace -- Nov. 11, 1918," suggested a palpable disdain for life after wartime:

"Looking forward I could see

Life like a festering sewer

Full of the fecal Pacafists [sic]

Which peace makes us endure"

12. Douglas MacArthur (1880 - 1964)

Few men have ever been as "born for war" as Douglas MacArthur. As Biography observes:

"His father, Arthur, was a captain at the time of Douglas’ birth, and had been decorated for his service in the Union Army during the Civil War. Douglas’ mother, Mary, was from Virginia, and her brothers had fought for the South during the Civil War. The base where Douglas was born was just the first of several military posts on which he would live during his youth."

MacArthur first distinguished himself during World War I when he was put in command of the "Rainbow Division." In 1918, "he participated in the St. Mihiel, Meuse-Argonne and Sedan offensives, during which he repeatedly distinguished himself as a capable military leader."

Were that the only global conflict MacArthur participated in, his reputation may have been more affected by his actions as Army chief of staff in the 1930s, when the Great Depression caused MacArthur to become concerned (and some say "paranoid") about the threat of Communism, and he ignored orders from the President in order to set the Army against his fellow World War I veterans during the infamous Bonus March of 1932.

MacArthur's actions in the Pacific, however, both during and after World War II, are what he's best remembered for. He had a series of successful military victories against the Japanese military in the region, even while the bulk of his superiors' focus was on Europe. At the end of the war, MacArthur was named supreme Allied commander by President Harry S. Truman, and oversaw the rebuilding of Japan for six years.

MacArthur's career ended unceremoniously. He was extremely vocal about his disagreement with President Truman about strategy in the Korean War (he wanted to expand the conflict into China), which led to the President relieving him of his command. His later suggestion to President Dwight D. Eisenhower that nuclear weapons be deployed in Korea to resolve the conflict further damaged his reputation.

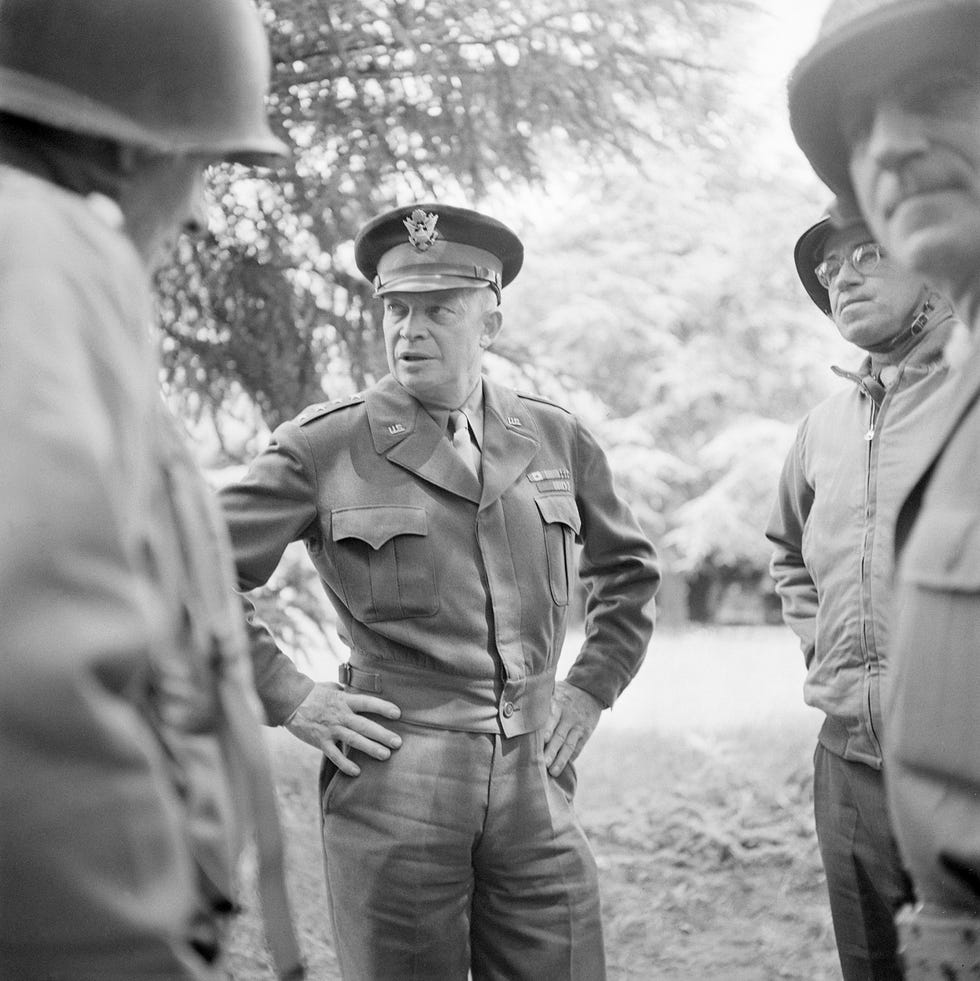

13. Dwight D. Eisenhower (1890 - 1969)

Dwight D. Eisenhower is one of only five U.S. Presidents to have never previously been elected to previous public office, and the last who had a military background.

A West Point graduate, Eisenhower initially served under MacArthur as assistant military advisor to the Philippines. During World War II, he led the Allied invasion of North Africa, known as Operation Torch, before playing a major role in the most well-known American action of World War II, D-Day.

On June 6, 1944, Eisenhower commanded the Allied forces in the invasion of Normandy. He would be promoted to the rank of five-star general in December of that year. After World War II, he served as military governor of the U.S. Occupied Zone in Germany, and later, the Supreme Allied Commander of NATO.

Both major political parties sought to "draft" Eisenhower, who ultimately chose to run on the Republican ticket. Winning "by a landslide," Eisenhower would serve two terms as President, bringing the Korean War to an end and vocally pursuing peace with the Soviet Union. Decades later, it would be revealed that Eisenhower's administration had, however, employed a great deal of covert action throughout the world, including two CIA-backed coup d'etats.

Delivering his farewell address, Eisenhower expressed concerns about the manner in which commerce had become intertwined with military spending and strategy, warning Americans that "we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex."

No comments:

Post a Comment