Andrew Hammond

UK Prime Minister Winston Churchill famously described Russia during the Second World War as a “riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma.” Yet, fast forward almost a century later and similar sentiments are felt today toward India by many Europeans.

The relationship between Europe and the world’s most populous democracy is a tantalizing mix of complexity, ambiguity, frustration and wonder too. This was encapsulated in a report released this month by the European Parliament, which rightly asserted “the partnership has not yet reached its full potential,” despite momentum in recent years. This viewpoint is widely shared across the continent with, for instance, a report by the Jacques Delors Institute in France recently stating that “EU-India economic relations are well below their potential.”

To be sure, perceptions of New Delhi have changed dramatically across much of the bloc in recent decades. Back then, India was aligned with the Soviet Union and was a protectionist economy moving away from the colonial era. Much of Europe therefore had a remote relationship with the Asian giant.

Today, however, India is a €3 trillion ($3.3 trillion) economy with vast potential. It is also increasingly aligned with Europe and the wider West, despite disagreements over key issues including Ukraine.

The EU 27 nations (taken as a whole) and India are the world’s two largest democracies, while continental Europe is India’s largest single trade and investment partner, and that is why a bilateral trade deal is a key potential prize for both parties. There are also converging interests around shared defense mechanisms, including for maritime security in the Indian Ocean where 40 percent of bilateral trade passes.

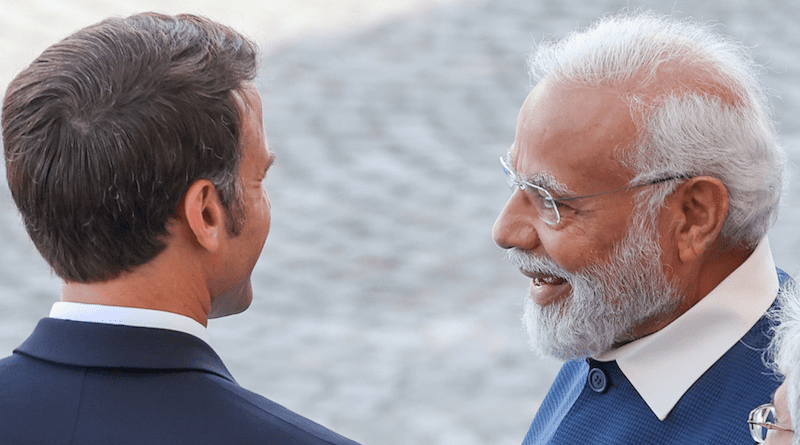

The latest signal of the potential upside in relations comes this week when French President Emmanuel Macron will be the chief guest at the Indian Republic Day celebrations on Jan. 26. This honor reflects both the respect that Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Macron appear to have for each other but also the mutual regard France and India have for each other, especially in defense, security, civilian nuclear cooperation and emerging technologies.

Last year, Modi was also the guest of honor at the annual Bastille Day celebrations in Paris. The prime minister was joined by Indian troops in the military parade marking what Macron called “a new phase in the strategic partnership between France and India.”

The Indian government last year approved the purchase of 26 naval variants of the Rafale combat jet from France, building on an earlier acquisition of 36 Rafale jets for the Indian Air Force. Paris and New Delhi have also stepped up collaboration on maritime security in the Indian Ocean.

Part of France and wider Europe’s fascination with India is the belief that it is a potential future superpower that could play a huge balancing role in the 21st century vis-a-vis China. While India’s development lags behind China, one indication of future potential is that the Asian giant is believed by many demographers now to be the most populous nation in the world at almost 1.5 billion people, overtaking China — a potentially significant moment in human history. So, the nation that has long been the world’s largest democracy becomes the world’s largest country of any political stripe, a position it may hold for decades if not centuries to come.

India’s higher fertility rate means the population is forecast to continue growing for several decades with some predictions it could peak around 1.7 billion in the second half of the century. Moreover, India’s over 250 million people aged 15-24 is the largest in the world, and more than two-thirds of all Indians are between the ages of 15 and 59, so the country’s ratio of non-working-age adults (children and retirees) to working age adults is very low.

What much of Europe now wonders is whether and how New Delhi will seek to leverage this new global population stature with some talk of an “Indian century,” for the milestone comes at a time when New Delhi is trying to promote itself as a rising international player.

The concern in Europe is that, despite the warmth of relations that it enjoys with India, there is a misalignment on key security issues like the Ukraine war. Here, New Delhi has sought to balance its relations between its remaining dependence on Russia, including for energy, and the West.

Moreover, Russia continues to be India’s largest arms supplier even though its share has dropped to about 50 percent from 70 percent due to New Delhi’s decision to diversify its portfolio and boost domestic defense manufacturing. This could leave India vulnerable to US sanctions from legislation such as the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act, which prohibits any country from signing defense deals with Russia, Iran and North Korea.

There is also some concern in Europe over India’s human rights record under Modi. This includes the treatment of Sikh and Christian minority groups by the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party, which he heads. Indeed, Modi himself was once subject to US and UK travel bans over 2002 communal violence during his tenure as chief minister of the western Gujarat state that killed around 1,000 people, mostly Muslims.

Nonetheless, if key European leaders, including Macron, continue to prioritize ties with India, such controversies will continue to be largely deemphasized. The huge appetite for greater economic and security collaboration, as Europe seeks to offset cooling relations with Beijing and Moscow with warmer ties with New Delhi, is trumping all else.

• Andrew Hammond is an associate at LSE IDEAS at the London School of Economics.

No comments:

Post a Comment