ALEX HOLLINGS

The F-16 Fighting Falcon, known affectionately by many pilots as the Viper, is the most widely operated fighter aircraft on the planet for a reason.

In an era when fighter designs were largely focused on what could be argued were glamour metrics like top speed and service ceiling, the F-16 emerged as the embodiment of a new approach to air warfare. Using a classified analysis of air-to-air combat as its guide, General Dynamics devised a fighter that emphasized performance within the specific speed-envelope in which dogfights were likely to occur.

The result was an aircraft that may not set any speed or climbing records like the F-15 Eagle that preceded it, but that could nonetheless outmatch, outturn, and outperform nearly any fighter it could come across… and all for less than half the cost of top-tier fighters of its day.

An F-15 and two F-16 flying in formation.

Much like today’s F-35, when the F-15 first emerged in the early 1970s, its unparalleled performance came with a nearly unparalleled price tag. Early F-15As came with a sticker price of some $28 million per aircraft – which adjusted to today’s inflation shakes out to about $227.5 million a piece. That means a single F-15 cost Uncle Sam nearly as much as three F-35As do today.

This left many Defense officials concerned that the U.S. Air Force simply couldn’t afford to make the Eagle the real backbone of America’s fighter fleet.

The opportunity was exactly what a small group of Air Force officials, defense analysts, and industry insiders collectively known as the “Fighter Mafia” were waiting for. Unlike earlier airborne powerhouses like the F-4 Phantom II, or more modern tactical rocket ships like the F-15 Eagle, the Fighter Mafia prized agility over sheer power, and affordability over technological complexity.

THE FIGHTER MAFIA

Widely recognized as one of the U.S. Air Force’s best jet pilots in the 1950s, John Boyd was among the minds behind the Energy Maneuverability Theory.

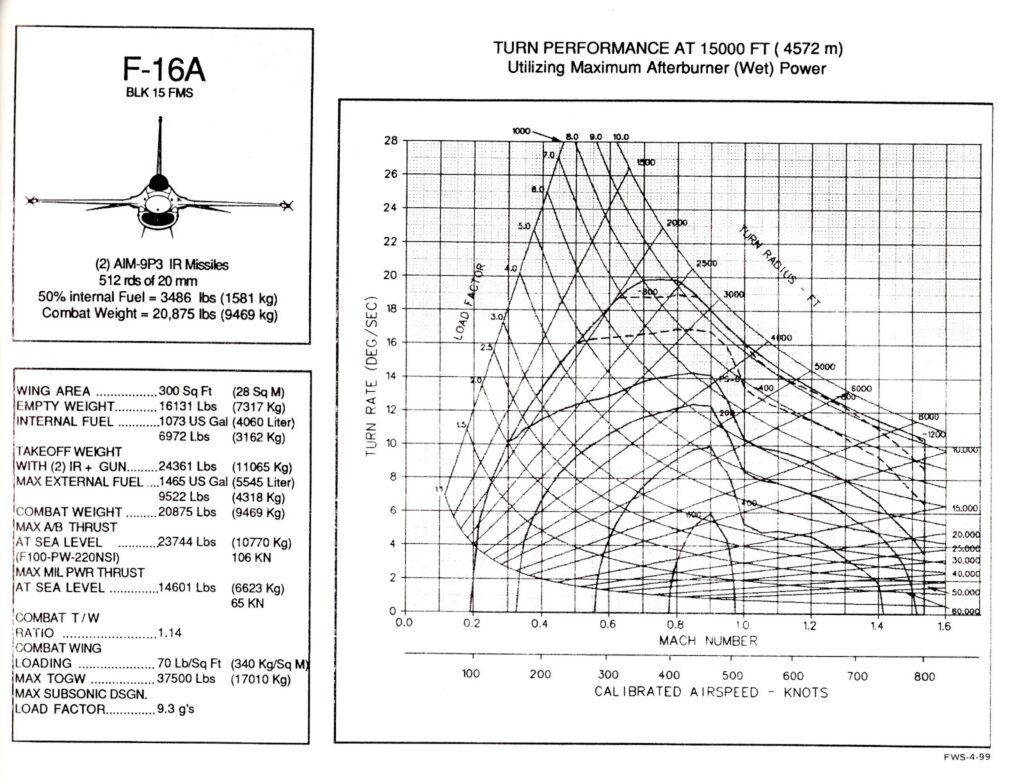

While the prevailing wisdom of the day prioritized things like top speed and weapon capacity over nearly all else, the Fighter Mafia championed something they called the Energy Maneuverability Theory (E-M theory or EMT). This theory was largely borne out of the lived experiences of fighter pilot John Boyd, who flew combat missions over Korea in his F-86 Sabre before going on to become a prolific instructor at the Air Force’s Fighter Weapons School, where he pioneered the idea that dogfighting wasn’t an art, but was instead a quantifiable science.

E-M Theory saw all aircraft maneuvers as an exchange of potential and kinetic energy, creating a framework to understand how fighters can gain, lose, and, most importantly, maintain energy as they fight.

To oversimplify the concept, energy is derived from an aircraft’s speed and altitude (reflected as kinetic or potential energy), and pilots must trade one or the other to maneuver. When modern fighter pilots say, “speed is life,” this is what they’re referring to – because outmaneuvering inbound missiles, for instance, costs speed, and the more you expend, the less you have available for further maneuvers; at least, until you can recoup it by accelerating or climbing. E-M theory made it possible to design fighters and tactics that would preserve as much energy as possible throughout a fight, in order to maintain the advantage.

By utilizing the fundamentals of E-M theory, Boyd and the rest of the Fighter Mafia argued they could design a fighter that was twice as maneuverable as the F-4D, with twice the combat radius at a bit more than half the weight, and all with a massive reduction in overall cost. Their proposal soon caught the attention of the Pentagon, which, in January of 1972, launched a formal effort based on the concept. This effort directly resulted in the development of both the F/A-18 Hornet and, most famously, the F-16 Fighting Falcon.

Energy Maneuverability diagram for the F-16A.

Yet, not everything the Fighter Mafia proposed panned out. They could be described as dogfight purists, who believed fighter aircraft shouldn’t be burdened with heavy avionics systems like onboard radar, and instead should focus on being extremely light and agile, only leveraging guns and short-range infrared-guided missiles. There’s a reasonable argument to be made that the F-16 truly found success once its design team departed from the Fighter Mafia’s design principles, going on to include things like onboard radar and equipping the Viper with longer-ranged radar-guided air-to-air missiles that would come to be the foundation of both the platform’s Beyond Visual Range (BVR) capability set and its renowned air-to-ground chops.

However, even if much of what the Fighter Mafia preached could be considered dated already by the time they began campaigning for a new lightweight fighter, the impact the Energy Maneuverability theory had on military aviation simply can’t be discounted.

THE VIPER EMERGES

General Dynamics F-16 proposal wrang in at just over $6 million per fighter in 1975 currency, or a bit shy of just $36 million today, but its aerobatic capability was even more impressive than its price tag.

Unlike previous fighter designs, the F-16 was the world’s first fighter to come with fly-by-wire control that passed off flight control duties to a computer that took its cues from the pilot. This revolutionary technology made it possible to create a fighter with an inherently unstable design – something seen as impractical, if not impossible, in previous fighters because human pilots simply couldn’t keep up with the constant corrections required to keep the aircraft under control.

This inherent instability reduced the amount of energy required to perform aerobatic maneuvers. Put simply, rather than using energy to make a stable jet maneuver, the F-16 used computer controls to keep it stable, and had aerobatic maneuvering as its natural state. As a result, the Viper became among the first (if not the first) fighters to easily perform 9G maneuvers with a full tank of gas and combat load.

The effort resulted in a jet that felt as stable as a commercial airliner in level flight, while also being able to outturn every fighter in the U.S. arsenal until the emergence of the thrust-vectoring F-22 Raptor in 2005.

Today, the F-16 is recognized as among the most dominant dogfighters of its generation, with many contending that it stands undefeated in air combat thanks to 76 victories and a single reported (but controversial) loss that is now widely attributed to friendly fire. But despite the design’s focus on air combat, the F-16’s speed, agility, and versatility soon set it apart as America’s first truly multi-role fighter platform, proving so dominant in attack operations early in its career that despite its dogfighting pedigree, every F-16 to roll off the assembly line since 1981 has come standard with the built-in structural and wiring provisions required for air-to-ground ops.

In 1991’s Operation Desert Storm, F-16s flew more combat sorties than any other aircraft, the vast majority of which were air strike operations. One such mission even saw an F-16 piloted by Major Emmett Tullia dodge a series of six surface-to-air missiles launched at it in rapid succession. It wasn’t until after the mission that Tulia came to learn that his flares and chaff were not functioning – and he’d managed to dodge the half dozen missiles thanks to nothing more than pilot skill and the F-16’s incredible maneuverability.

The F-16’s combination of extreme capability and low cost led to it becoming the backbone of not just the U.S. Air Force, but of air forces around the world, with more than 4,600 F-16s having been built throughout its production run so far and new Vipers continuing to roll off the assembly line.

And despite the emergence of 5th generation fighters like the F-35, the F-16 remains the backbone of the U.S. Air Force to this very day.

No comments:

Post a Comment