Micah McCartney

China's economy, once believed to be breathing down the neck of the United States, is losing steam relative to its geopolitical rival.

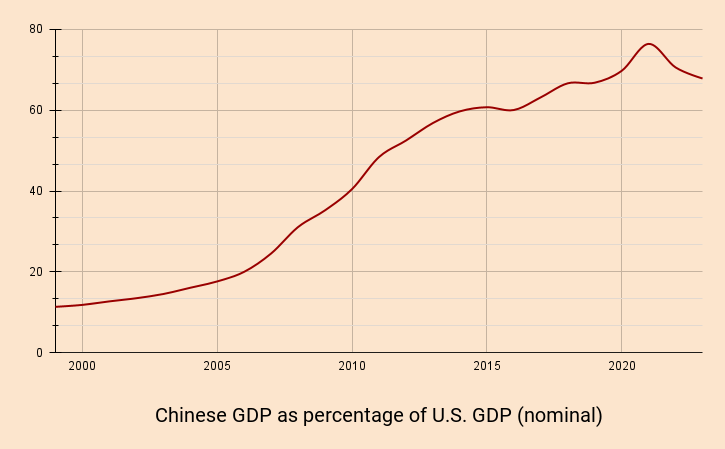

The World Bank now estimates the world's second-largest economy, as represented in Beijing's official reports, was two-thirds the size of Washington's last year, down from 70 percent the previous year and 76 percent in 2021.

The country's recovery from its yearslong anti-virus policies during the COVID-19 pandemic undershot some analysts' expectations, marred by months of rolling lockdowns, a real estate market on the ropes and declining foreign direct investment.

To eventually supplant the U.S. as the No. 1 economic powerhouse, experts said China needed to maintain a minimum annual GDP growth of 5 percent.

This graph shows China's nominal GDP as a percentage of the U.S.'s GDP from 2019 to 2022 and includes the World Bank's estimates for 2023. China's slowing economic growth has moved economists to revisit earlier predictions China would supplant the U.S as the world's largest economy by the end of the decade.

China, after reporting double-digit growth for the first two decades this century, likely met that 5 percent threshold last year, according to leading financial institutions like the International Monetary Fund. However, it is forecast to register a modest 4.6 percent in 2024.

Economic analysts previously observed that Chinese leader Xi Jinping's report to the Communist Party's national congress in 2022 included less bullish benchmarks, which he laid out in per capita income rather than in overall GDP—a departure from the lofty goal, announced two years prior, of doubling both GDP and GDP per capita within a decade and a half.

Beijing appears to be "quietly abandoning its ambition" to overtake the U.S. as the world's top economy, Chicago-based economic analyst Houze Song said at the time.

In 2022, China's nominal GDP, or GDP without adjustment for inflation, was evaluated at $17.96 trillion—70.6 percent of the U.S.'s $25.44 trillion.

"The fundamentals sustaining China's steady growth in the long run have not changed, and the world has shown confidence in China's economy this year," Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Wang Wenbin told a regular press briefing in early January.

He pointed to a comment by Steven Barnett, the IMF's representative in China, who predicted the nation's economy would see "sound growth" this year and continue to account for a third of the world's economic activity.

China watchers have questioned the official economic numbers Beijing has published.

Li Keqiang, the country's late former premier and economic reformist, in 2007 acknowledged the GDP data published by the government was "man-made" and thus unreliable, according a diplomatic cable published by WikiLeaks.

The Chinese Embassy in Washington, D.C., did not immediately respond to Newsweek's written request for comment.

Despite vigilant government censorship and attempts to scrub conversations about poverty from the Chinese internet, worries persist. Citizens and businesses alike are holding onto cash instead of spending or investing it, Adam Posen, president of the Peterson Institute for International Economics, wrote last fall in the magazine Foreign Affairs.

Posen, who described China as suffering from "economic long COVID," said Beijing "acted increasingly capricious and arbitrary in restricting economic activity" in the years leading up to, and especially during, the pandemic.

The remedy—a wholesale effort to assure everyday Chinese there are checks on state-backed intrusion into their pocketbooks—was not forthcoming, he said, thus limiting the effect of government efforts to stimulate the economy.

It was a common problem among authoritarian regimes, Posen said. They often negate growth previously achieved by the private sector by acting to "tighten the screws of government control in counterproductive ways."

No comments:

Post a Comment