Chris Lau and Simone McCarthy

On a brisk December day, junior high school students in Fuzhou, southeast China, converged at a country park to study the thoughts of Chinese leader Xi Jinping.

Unfurling a red banner that declared their outing a “walking classroom of politics and ideology,” they sought enlightenment by retracing the footsteps Xi took on his 2021 visit to the neighborhood, according to a state-affiliated local news outlet.

Another group of youngsters in the northern coastal city of Tianjin toured a fort to reflect on “the tragic history of Chinese people’s resistance to foreign aggression.”

The trips are part of a ramping up of nationalist education in China in recent years – now codified into a sweeping new law that came into effect earlier this week.

That “Patriotic Education Law,” aimed at “enhancing national unity,” mandates that love of the country and the ruling Chinese Communist Party be incorporated into work and study for everyone – from the youngest children to workers and professionals across all sectors.

It is meant to help China “unify thoughts” and “gather the strength of the people for the great cause of building a strong country and national rejuvenation,” a Chinese propaganda official told a news briefing last month.

The push for a love of country and the Communist Party is far from new in China, where patriotism and propaganda have been an integral part of education, company culture and life since the People’s Republic was founded nearly 75 years ago.

And Chinese nationalism has thrived under Xi, the country’s most authoritarian leader in decades, who has pledged to “rejuvenate” China to a place of power and prominence globally and encouraged a combative, “wolf warrior” diplomacy amid rising tensions with the West.

Ultra-nationalism has flourished on social media, where anyone perceived as slighting China – from live-streamers and comedians to foreign brands – will face a fierce backlash and boycotts.

Attendees sing a patriotic song in Hangzhou, Zhejiang province on September 15, 2019 at an event marking the 70th anniversary of the founding of the People's Republic of China.

The new rules mark the latest expansion of Xi’s efforts to deepen the party’s presence in all aspects of public and private life.

But this time, they also follow years of stringent Covid-19 controls in China, which ended late in 2022 after young people across the country took to the streets in unprecedented protests against Xi’s government and its rules.

They also come as the economy slumps and youth unemployment has reached a record high – raising the potential for more discontent.

Experts said Beijing may see the new legal framework as a way to drum up nationalism and consolidate power to ensure social stability amid the challenges ahead.

China has long relied on its people to buy into its vision like an unwritten “social contact,” but it is now “in for a bumpy ride in the coming years,” said Jonathan Sullivan, an associate professor specializing in Chinese politics at the University of Nottingham.

“There could be challenges to that if there’s a protracted economic downturn … they’re doing the work to make sure the politically correct way of thinking is completely locked down, consolidating beyond doubt that the party’s way is the only way for China, and that if you love China, you ought to love the party,” he said.

That message has been hammered home in once outspoken Hong Kong following the huge democracy protests that erupted there in 2019.

Since then, Beijing has made clear it wants a new generation of patriots incubated in the city, rolling out patriotic education rules and political restrictions that forbid anyone deemed unpatriotic from standing for office.

The introduction of the law also coincides with the 75th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China this coming October 1. Officials will be under pressure to ensure a celebration of patriotism – and to stamp out any possibility for dissent.

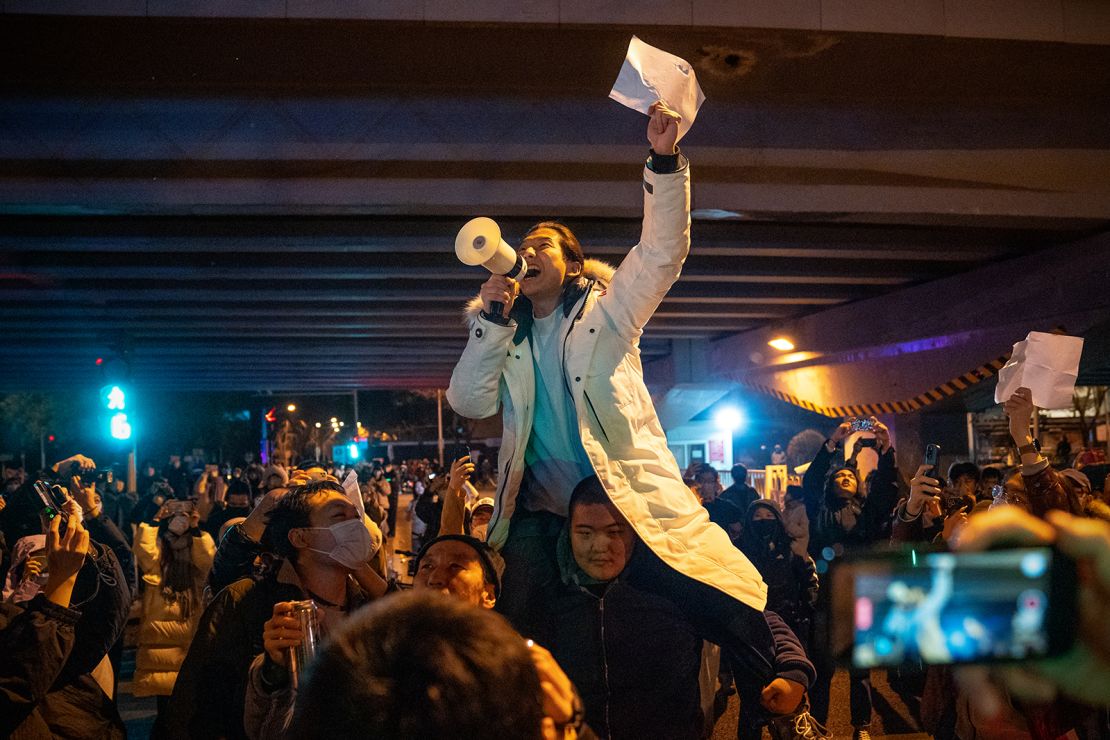

A demonstrator holds a blank sign and chants slogans during a protest in Beijing on November 28, 2022.

Patriotic curriculum for all walks of life

Under the law, professionals – from scientists to athletes – should be nurtured to profess “patriotic feelings and behavior that bring glory to the country.”

Local authorities are required to leverage cultural assets, such as museums and traditional Chinese festivals, to “enhance feelings for the country and family,” and step-up patriotic education through news reports, broadcasting and movies.

Religious bodies should also “strengthen religious staff and followers’” patriotic sentiment and their awareness of the rule of law – a stipulation in line with China’s push to “sinicize” and tighten its control over religion.

The latest legislation follows a 2016 directive from the Ministry of Education to introduce across-the-board patriotic education at each stage and in every aspect of schooling, which plays a major part in the new unified law.

It also follows past efforts, such as smartphone apps for people to “learn about new socialist thought” - including a lesson on how “Grandpa Xi led us into the new era” - and for adults to read up and take quizzes on Xi’s latest theories.

The latter was deemed a success in terms of downloads – as all 90 million Communist Party members were ordered to use it alongside many employees of state-owned enterprises.

People wave Chinese flags to mark China's National Day in Hong Kong on October 1, 2023.

The new rules affirm that patriotic education will be blended into school subjects and teaching materials “at all grades and all types of institutions,” while parents at home are required to guide their children and encourage them to take part in patriotic activities.

“(This has to do) with Xi’s consolidation of power. He wants patriotic education to start early,” said Alfred Wu, an associate professor at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy at the National University of Singapore.

He said the move is aimed at cultivating a loyal mindset toward Xi from a young age, while also sending a message to the wider public that Beijing’s focus is now on consolidating Xi’s power following the economic boom of the past decade.

The new law also orders cultural establishments such as museums and libraries to be turned into venues of patriotic education activities and tourist destinations into places that “inspire patriotism.”

Schools are required to organize trips for students to visit these sites, which officials call “walking classrooms of politics and ideology.”

Such trips were not uncommon in the past, but the law now officially imposes a legal mandate for schools to do so.

China has other legislation aimed at stamping out unpatriotic behavior, such as banning the desecration of national flags and insults to soldiers. And under Xi in recent years, any dissent in China – even in the form of online comments that don’t toe the party line – is enough to land people in trouble with authorities.

But the latest law appears to hint at the introduction of penalties for acts not already punishable under existing laws, according to Ye Ruiping, senior law lecturer from Victoria University of Wellington in New Zealand.

For example, it states that behaviors “advocating, glorifying and denying acts of invasion, wars and massacres” and “damaging patriotic education facilities” could be subject to punishments, she said.

No comments:

Post a Comment