Michael Robbins, MaryClare Roche, Amaney A. Jamal, Salma Al-Shami, and Mark Tessler

Since October 7, the latest war between Hamas and Israel has claimed the lives of more than 15,000 Palestinians and over 1,200 Israelis. Scores more have been injured. The war has displaced more than 1.8 million Palestinians and left the fates of many of Israel’s people unknown; over 100 of those abducted in Israel remain hostages. Fighting has resulted in damage to 15 percent of the buildings in Gaza, including over 100 cultural landmarks and more than 45 percent of all housing units.

As many analysts have already declared, the high costs in Gaza have reverberated around the Arab world, reaffirming the salience and power of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in shaping regional politics. Yet it has been difficult to say exactly how much the attack has affected Arab attitudes—and in what particular ways.

Now, that is changing. In the weeks leading up to the attack and the three weeks that followed, our nonpartisan research firm, Arab Barometer, conducted a nationally representative survey in Tunisia in conjunction with our local partner, One to One for Research and Polling. By chance, about half the 2,406 interviews were completed in the three weeks before October 7, and the remaining half occurred in the three weeks after. As a result, a comparison of the results can show—with unusual precision—how the attack and subsequent Israeli military campaign have changed views among Arabs.

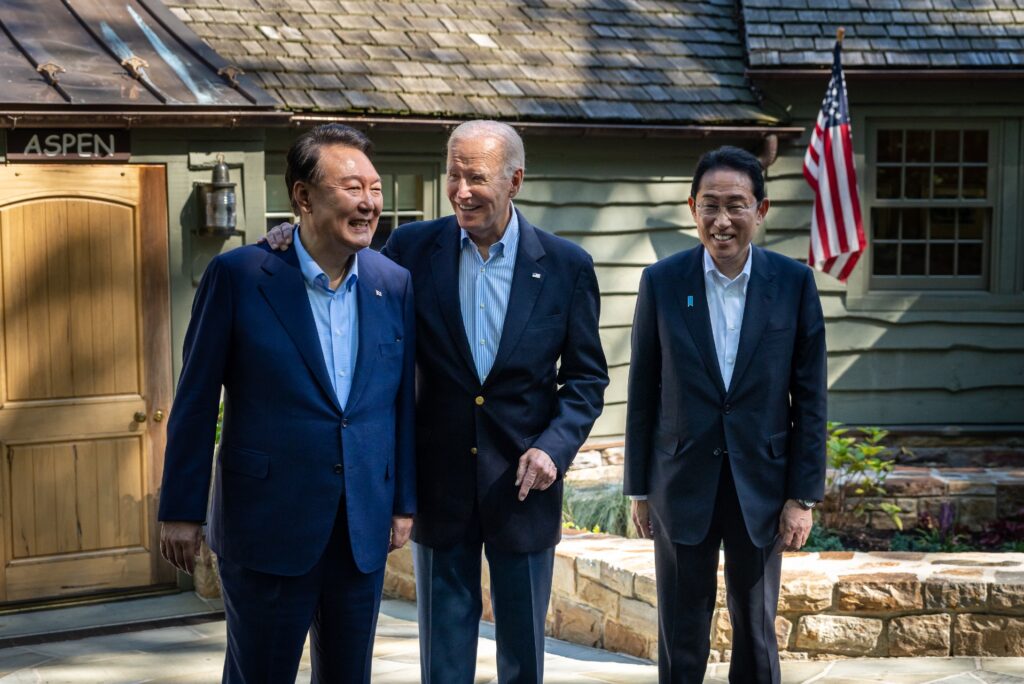

The findings are striking. U.S. President Joe Biden recently warned that Israel was losing global support over Gaza, but that is only the tip of the iceberg. Since October 7, every country in the survey with positive or warming relations with Israel saw its favorability ratings decline among Tunisians. The United States saw the steepest drop, but Washington’s Middle East allies that have forged ties to Israel over the last few years also saw their approval numbers go down. States that have stayed neutral, meanwhile, experienced little shift. And the leadership of Iran, which is ardently opposed to Israel, saw its favorability figures rise. Three weeks after the attacks, Iranian Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei has approval ratings that matched or even exceeded those of Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, known as MBS, and Emirati President Mohammed bin Zayed, known as MBZ.