Liane Hartnett

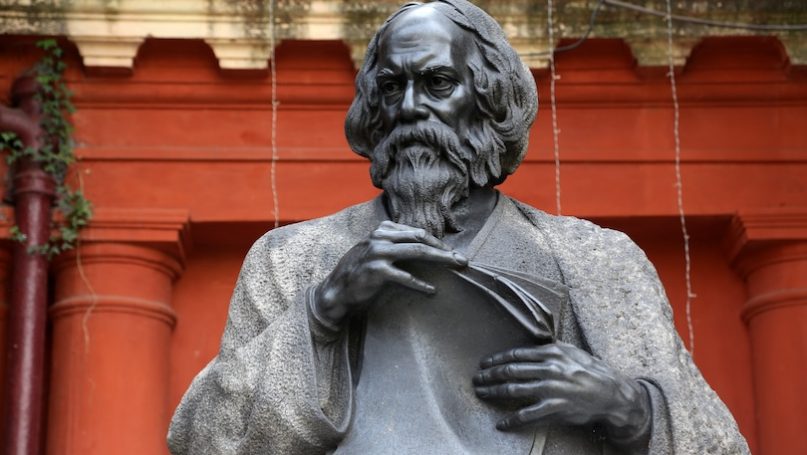

Endeavours to deprovincialize the discipline of International Relations (IR) including the embrace of global IR (Acharya and Buzan 2019), the recovery of neglected and erased political figures’ international thought (e.g., Owens, Rietzler, Hutchings and Dunstan 2022; Kapila 2021; Vitalis 2015), and the turn to literature as a site of international theorising (e.g. Hunt 2022; Mrovlje 2017) have collectively served to create space for a renewed focus on Rabindranath Tagore’s contribution to IR. Rabindranath Tagore was a Bengali polymath who described himself as a confluence of many cultures. After becoming the Nobel Laureate in Literature in 1913, he acquired the status of an international celebrity and traversed multiple political circles. In many ways, then, he was no marginal figure. Scholarship on Tagore’s life and works have long flourished in South Asia (e.g., Chakravarty and Chaudhuri 2017; Tuteja and Chakraborty 2017; Puri 2015; Haque 2010). A few prominent political theorists offer close and compelling engagements with his work (Berlin 2019; Nussbaum 2015; Sen 2006). Yet, but for some notable exceptions (e.g., Shani 2022; Devare 2018; Rao 2010), Tagore remains largely understudied in IR. This article seeks to redress this by offering a brief introduction to Tagore and contextualising and situating his early twentieth century international thought in the IR lexicon.

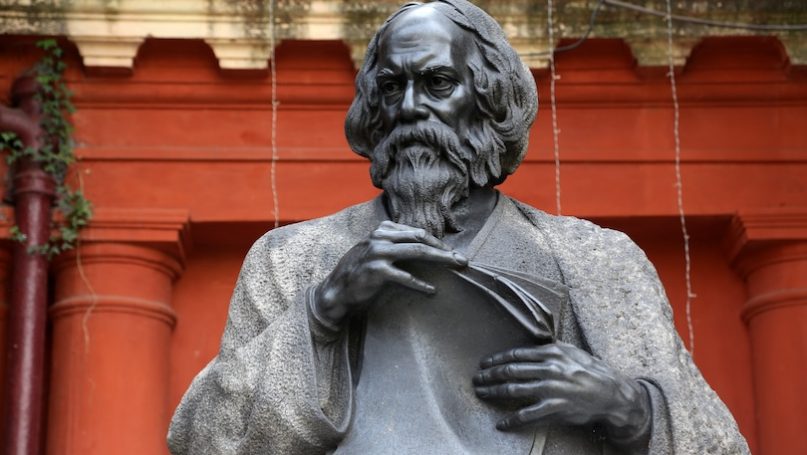

A Myriad Minded Man

Rabindranath Tagore was born on 7 May 1861 to Sharada Devi and Debendranath Tagore in Calcutta (present day Kolkata). At the heart of the Bengal Renaissance, the Tagores were the first family of Bengal (Vajpeyi 2012). Rabindranath’s grandfather ‘Prince’ Dwarkanath Tagore was a trader, banker and philanthropist who was a guest of Queen Victoria and King Louis Phillipe. His father, ‘Maharshi’ (Great Sage) Debendranath Tagore co-founded the religious reform movement, Brahmoism (Dutta and Robinson 1997; Collins 2012). Among Tagore’s many accomplished family members were the mathematician, philosopher, and poet, Dwijendranath Tagore, the first Bengali woman novelist, Swarnakumari Tagore, the artist and founder of the Bengal School of Art, Abanindranath Tagore, and the woman of letters, Kadambari Devi (Dutta and Robinson 1997).

Growing up in this immensely creative environment profoundly shaped Tagore’s development. It more than compensated for his unconventional formal education which included brief and often unsuccessful stints at four schools, and later, University College London. Indeed, in 1913, Tagore became the first non-European to win the Nobel Prize in Literature. In 1915, in recognition of his services to Literature, he was awarded a knighthood. In 1940, the University of Oxford conferred him with an honorary doctorate. Upon gaining independence, India and Bangladesh adopted his compositions as national anthems. Less celebrated – but no less significant – were his ecological or ‘rural reconstruction’ initiatives at Sriniketan, and the founding of his global university, Visva Bharati. The former influenced both the government of India’s development practices and inspired the formation of Dartington Trusts (Dutta and Robinson 1997), while the latter was dedicated to the study of humanity and had among its many visitors, the International Relations scholar, Merze Tate (Vitalis 2015). Tagore, then, was a myriad minded man: he was a poet, author, artist, composer, ecologist, educator, and a political figure.