David Scott

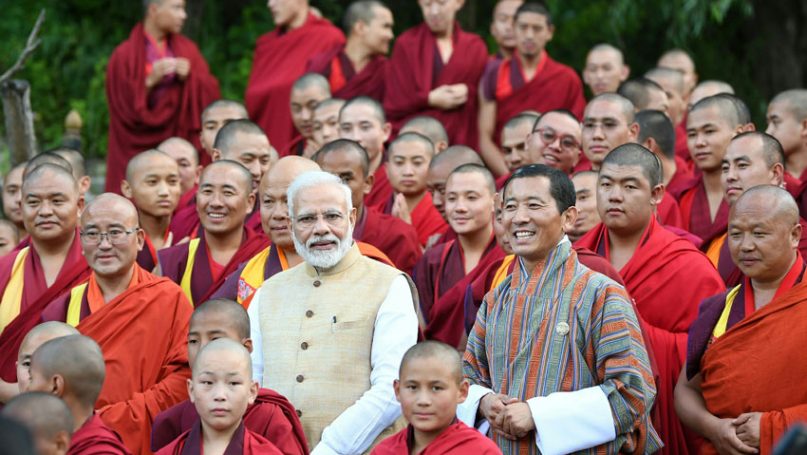

Strategic utilization of Buddhism in Indian foreign policy is a feature that has become particularly noticeable in the last decade, under Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) which took power in 2014. Modi has pushed an “Indian vision of Buddhism” which “appeals to ancient history while rooted in contemporary geopolitical concerns” (Lam 2022). The geopolitical concerns reflect the deterioration in India’s relations with China on show with confrontation, casualties and conflict along India’s Buddhist Himalayan frontier – at Doklam in 2017, Galwan in 2020, and Yangtse in December 2022.

Leading analysts were already noting by the end of 2014 that “the PM has put Buddhism at the heart of India’s vigorous new diplomacy.” Two examples suffice from September 2015. At the Mahabodhi Temple in Bodh Gaya, Modi proclaimed:

That same month, Modi also initiated a “…‘Samvad’ – Global Hindu-Buddhist Initiative”, in which “India is taking the lead in boosting the Buddhist heritage across Asia.” This Samvad initiative was enthusiastically embraced by Japan’s leader Shinzo Abe. A Samvad framework was then pushed jointly by India and Japan in subsequent years, a geocultural use of Buddhism to offset the geoeconomic allure of China’s Silk Road project.

India is a rising power, with rising hopes for influence in and around its immediate and extended neighborhood. Its power projection is multi-faceted, with geocultural linkages sought for geopolitical purposes. Kishwar noted the “rising role of Buddhism in India’s soft power strategy” in 2018. This soft power Buddhism-facilitated diplomacy is also evident with regard to India’s strategic partnerships with Japan and Mongolia (Sarmah 2022), as well as with Vietnam and South Korea, and with regard to Indian outreach to Thailand, Myanmar and Sri Lanka. Tibetan Buddhism has been “a source and strength of Indian soft power diplomacy” (Tsultrim 2020), along the Himalayas with regard to bilateral relations with Nepal and Bhutan, and further afield with regards to Mongolia.