Dalton Bennett

The engineers at a once-bustling industrial hub deep inside Russia were busy planning. The team had been secretly tasked with building a production line that would operate around-the-clock churning out self-detonating drones, weapons that President Vladimir Putin’s forces could use to bombard Ukrainian cities.

A retired official of Russia’s Federal Security Service was put in charge of security for the program. The passports of highly skilled employees were seized so they could not leave the country. In correspondence and other documents, engineers used coded language: Drones were “boats,” their explosives were “bumpers,” and Iran — the country covertly providing technical assistance — was “Ireland” or “Belarus.”

This was Russia’s billion-dollar weapons deal with Iran coming to life in November, 500 miles east of Moscow in the Tatarstan region. Its aim is to domestically build 6,000 drones by summer 2025 — enough to reverse the Russian army’s chronic shortages of unmanned aerial vehicles, or UAVs, on the front line. If it succeeds, the sprawling new drone factory could help Russia preserve its dwindling supply of precision munitions, thwart Ukraine’s effort to retake occupied territory and dramatically advance Moscow’s position in the drone arms race that is remaking modern warfare.

Although Western officials have revealed the existence of the facility and Moscow’s partnership with Tehran, documents leaked from the program and obtained by The Washington Post provide new information about the effort by two self-proclaimed enemies of the United States — under some of the world’s heaviest sanctions — to expand the Kremlin’s drone program. Altogether, the documents indicate that, despite delays and a production process that is deeply reliant on foreign-produced electronic components, Moscow has made steady progress toward its goal of manufacturing a variant of the Iranian Shahed-136, an attack drone capable of traveling more than 1,000 miles.

The documents show that the facility’s engineers are trying to improve on Iran’s dated manufacturing techniques, using Russian industrial expertise to produce the drones on a larger scale than Tehran has achieved and with greater quality control. The engineers also are exploring improvements to the drone itself, including making it capable of swarm attacks in which the UAVs autonomously coordinate a strike on a target.

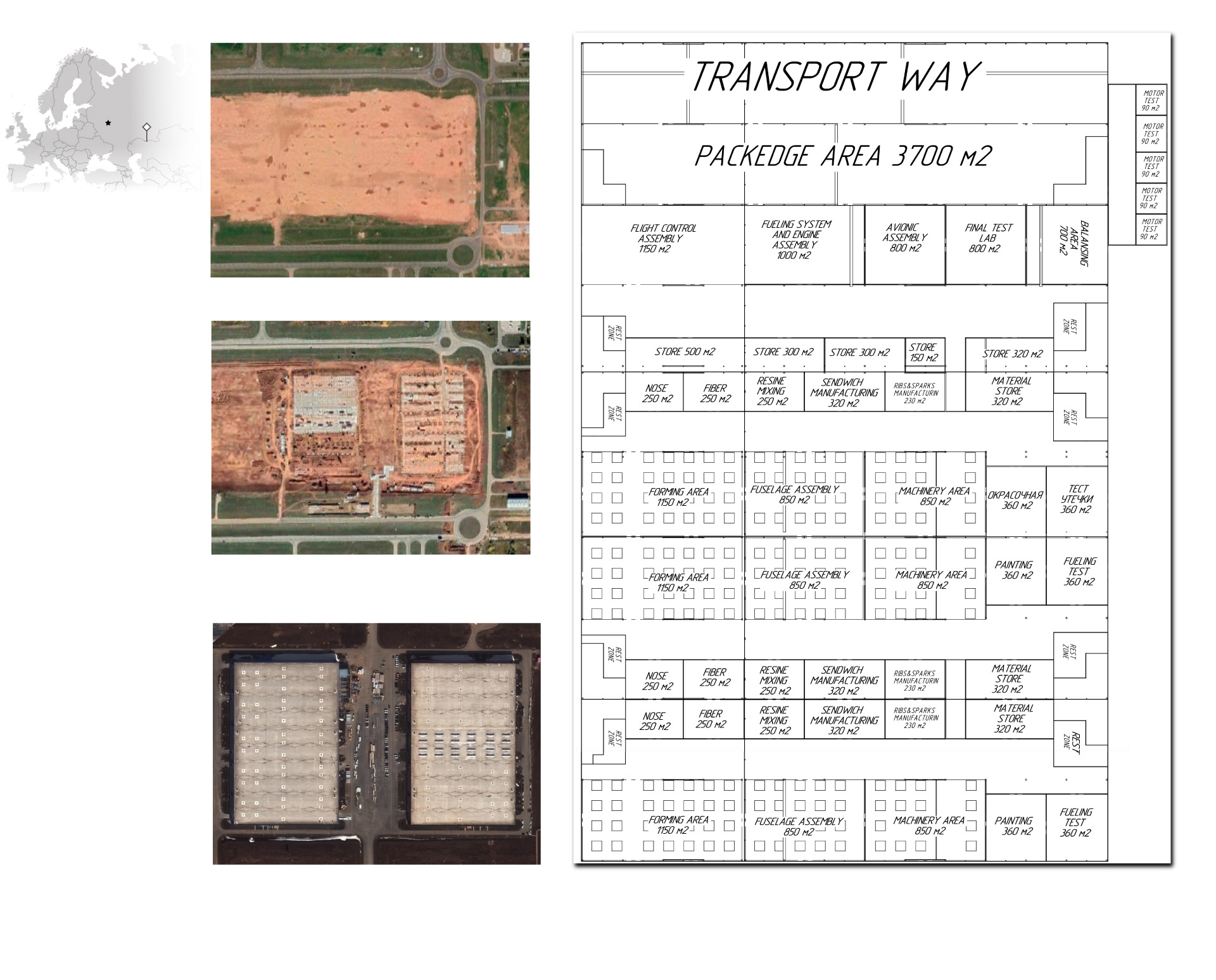

Construction of facilities Alabuga later used to establish a drone production line.

Preliminary floor plan for part of the drone assembly line.

Researchers at the Washington-based Institute for Science and International Security, who reviewed the documents pertaining to the production process at the request of The Post, estimated that work at the facility in the Republic of Tatarstan’s Alabuga Special Economic Zone is at least a month behind schedule. The facility has reassembled drones provided by Iran but has itself manufactured only drone bodies, and probably for not more than 300 of the UAVs, the researchers concluded. Alabuga is unlikely to meet its target date for the 6,000 drones, they said.

Even so, David Albright, a former U.N. weapons inspector who helped lead the research team that studied the documents, said: “Alabuga looks to be seeking a drone developmental capability that exceeds Iran’s.”

The Post obtained the documents from an individual involved in the work at Alabuga but who opposes Putin’s invasion of Ukraine. The individual decided to expose details of the effort in the hope that international attention might lead to additional sanctions, potentially disrupting production and bringing the war to an end more quickly, the person told The Post.

“This was the only thing I could do to at least stop and maybe create some obstacles to the implementation of this project,” the person said, speaking on the condition of anonymity because of safety concerns. “It has gone too far.”

The documents, dating from winter 2022 to spring 2023, include factory-floor blueprints, technical schematics, personnel records, memorandums provided to Iranian counterparts and presentations given to representatives of Russia’s Defense Ministry on the status of the effort code-named “Project Boat.” The Russian-language news outlet Protokol reported on some of the documents in July.

The team led by Albright and senior researcher Sarah Burkhard said the documents “appear authentic” and “go to great length to describe supply-chain procurement, production capabilities, manufacturing plans and processes, as well as plans to disguise and hide the production of Shahed drones.”

The research team found that the project faces challenges — including “doubt about its ability to reach its desired staffing levels” — but cautioned that Russia might be able to overcome those difficulties.

“Russia has a credible way of building over the next year or so a capability to go from periodically launching tens of imported Shahed-136 kamikaze drones against Ukrainian targets to more regularly attacking with hundreds of them,” Albright told The Post.

Albright said the disclosure of the records makes it difficult for Iran — which has publicly declared it is neutral in the war — to claim that it is not helping Moscow develop the ability to manufacture drones at Alabuga.

The Russian government and Alabuga did not respond to requests for comment from The Post. The Kremlin has dismissed reports that it is receiving assistance from Tehran on drones, saying that Russia relies on its own research and development.

Iran’s mission to the United Nations also did not respond to a request for comment.

‘The flying moped’

While Russia has made breakthroughs in air defense and hypersonic missiles, its military was late to prioritize drone technology. To catch up, Moscow has had to turn to Iran, one of the few nations willing to sell it military hardware.

Last summer, Russia began receiving secret shipments of Iranian drones — many of them Shaheds — that were quickly deployed to prop up its flagging war effort, U.S. and other Western officials have said.

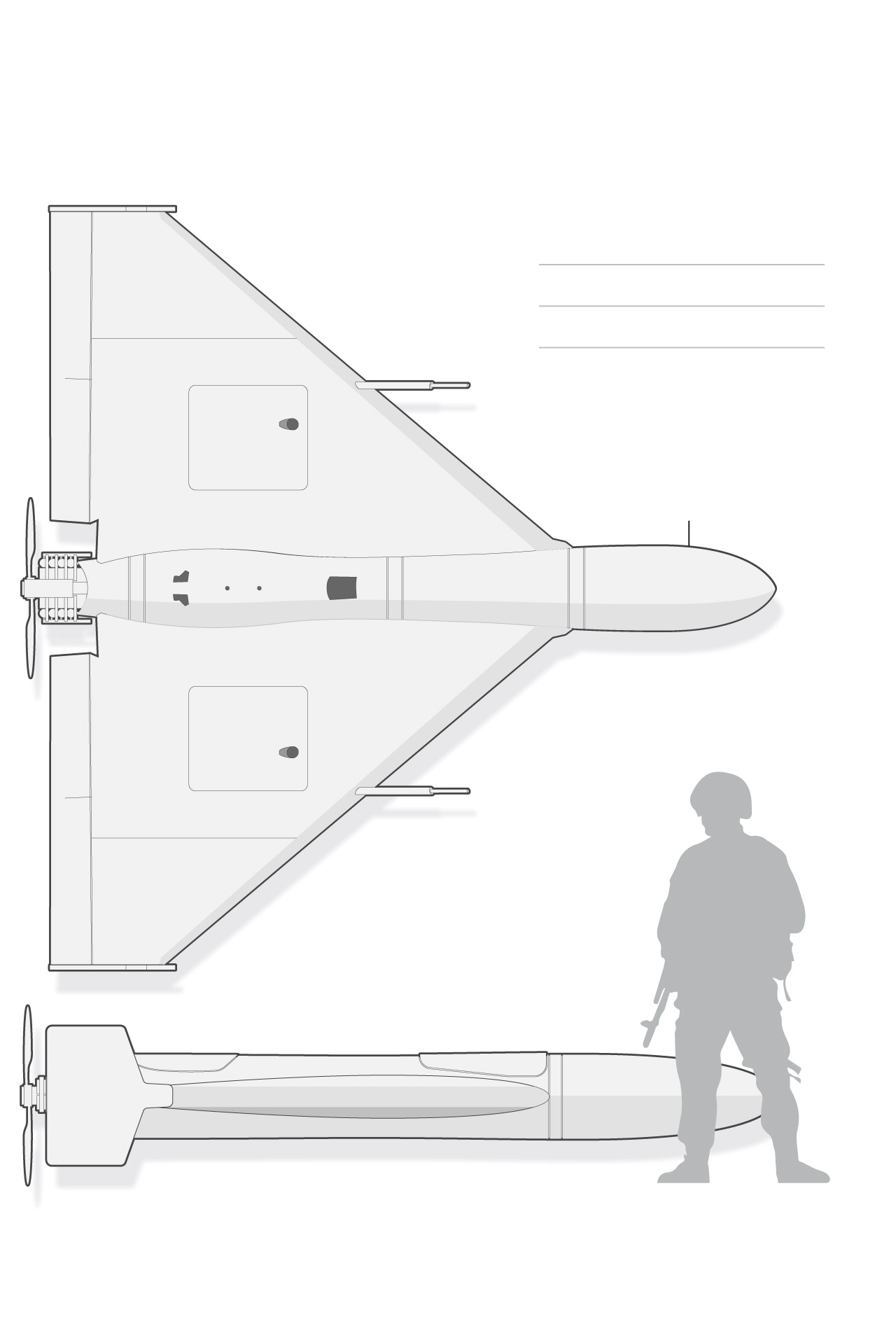

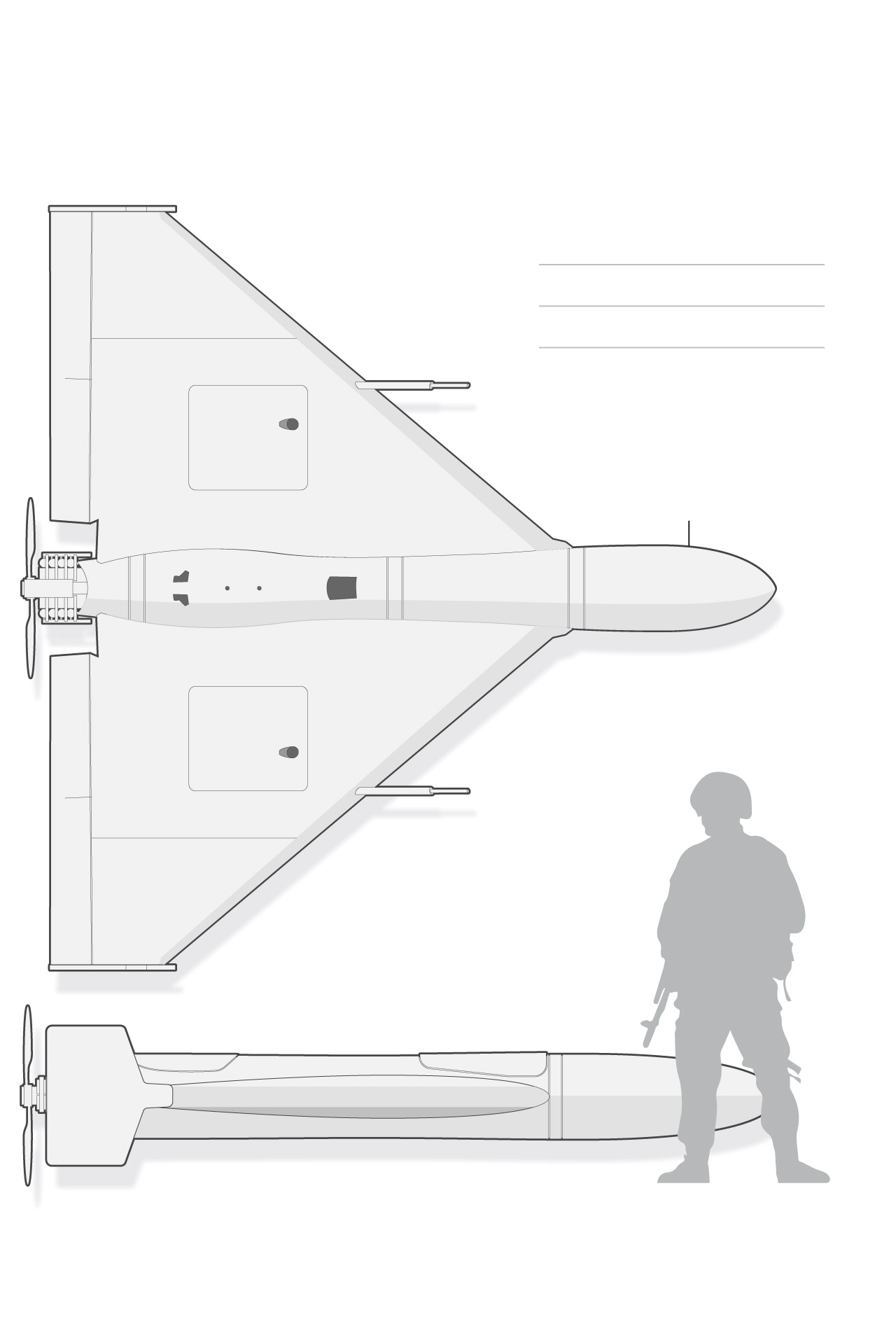

Iran’s Shahed-136 — Russia calls the drone the Geran-2 — can carry a 118-pound explosive payload toward a target that is programmed in before launch. Because the drone is powered by a noisy propeller engine, some Ukrainians have dubbed it “the flying moped.”

SHAHED-136 (IRAN)

Length: 11 feet

Max. speed: 115 mph

Approx. weight: 440 pounds

Range: About 1,100 - 1,500 miles

The Iranian Shahed-136

Russia is working toward manufacturing a variant of the Iranian drone, which it calls the Geran-2, to supplement its dwindling stockpile of precision weapons. The drone can deliver small payloads of explosives in self-detonating attacks.

Russia’s drones have struck targets deep inside Ukraine, degrading Kyiv’s precious air defenses and allowing Moscow to preserve its more expensive precision-guided missiles. The attacks, often targeting critical civilian infrastructure, have had a devastating impact on Ukraine’s war effort, knocking critical power grids offline and destroying grain stockpiles, according to Vladyslav Vlasiuk, an adviser to Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky.

“Those drones are much cheaper to produce compared to the damage they cause, and this is the problem,” Vlasiuk told The Post.

In November, a Kyiv-based think tank became one of the first nongovernmental organizations to examine the wreckage from a Russian Geran-2 drone downed in Ukraine. It found that key parts — the motor and warhead — were produced by Tehran. “We knew the drone was from Iran,” said Gleb Kanievskyi, the founder of the StateWatch think tank.

That month, Iran acknowledged it had provided drones to Russia but said it had done so only before the start of the war.

![]() Ukrainian firefighters work atop a destroyed building after a drone attack in Kyiv on Oct. 17, 2022. (Yasuyoshi Chiba/AFP/Getty Images)

Ukrainian firefighters work atop a destroyed building after a drone attack in Kyiv on Oct. 17, 2022. (Yasuyoshi Chiba/AFP/Getty Images)

In the past three months, Russia has attacked Ukraine with more than 600 of the self-detonating Shahed-136 drones, according to an intelligence assessment produced by Kyiv in July and obtained by The Post.

Conflict Armament Research, a weapons-tracking group based in Britain, examined two drones downed last month and concluded based on components it found that the Kremlin has started producing “its own domestic version of the Shahed-136.”

The Post reported in November that Russian and Iranian officials had finalized a deal in which the self-detonating drones would be produced at the Alabuga Special Economic Zone, a government-backed manufacturing hub designed to attract foreign investment. The cooperation included the transfer of designs, training of production staff and provision of increasingly hard-to-source electronic components.

“This is a full-scale defense partnership that is harmful to Ukraine, to Iran’s neighbors and to the international community,” White House National Security Council spokesman John Kirby said in June as the Biden administration confirmed plans by the two countries to build a drone production facility. Kirby said the plant “could be fully operational next year.”

Under the deal, the new documents show, Tehran agreed to sell Moscow what is effectively a franchise, with Iranian specialists sharing project documentation, locally produced or reverse-engineered components, and know-how. A document created in February by the project’s chief manager details the parameters of the effort and estimates the cost for some aspects of the project to be 151 billion rubles, more than $2 billion at the exchange rate at the time. Under agreements reached earlier, more than half of that sum was to go to Iran, which insisted on being paid in dollars or gold because of the volatility of the ruble, the individual who provided the documents said.

The effort — at a facility larger than 14 football fields and set to be expanded — is to be separated into three stages, according to a planning document. The first envisioned Iran’s delivery of disassembled drones that would be reassembled at the facility. The second called for the facility to produce airframes — the hollow bodies of the drones — that would be combined with Iranian-supplied engines and electronics. In the final and most ambitious stage, more than 4,000 drones would be produced with little Iranian assistance and delivered to the Russian military by September 2025.

Scarce components

The documents identify the sourcing of components required to build the Shahed-136 as an immediate challenge, after Western restrictions disrupted Russian access to foreign-produced electronics.

A detailed inventory, based on data provided to the Russians by Tehran, shows that over 90 percent of the drone system’s computer chips and electrical components are manufactured in the West, primarily in the United States. Only four of the 130 electronic components needed to build the drone are made in Russia, according to the document.

The research team led by Albright and Burkhard noted that none of the required items appears to be exclusively for use in military drones, and none is listed as a sensitive technology that is subject to export controls by the U.S. Commerce Department. The components would, however, fall under a near-blanket ban the United States recently imposed on the export of electronics to Russia, the team said.

The flight-control unit, used to pilot the drone, comprises 21 separate electronic components manufactured by the Dallas-based company Texas Instruments. At least 13 electronic components manufactured by the Massachusetts-based company Analog Devices are present in all of the drone’s major circuit boards, including an accelerometer critical for the craft’s operation that allows the UAV to navigate along a preprogrammed route if the GPS signal is lost.

One document highlights the need to develop a supply channel for various American components, including a Kintex-7 FPGA, a processor used in the drone’s navigation and communication system, made by a company that was acquired last year by California-based AMD. Without elaborating, another spreadsheet notes the domestic availability of Western-made components inside Russia and lists U.S.-based electronics distributors Mouser and DigiKey as potential suppliers.

AMD, DigiKey, Texas Instruments and Analog Devices told The Post that they comply with all U.S. sanctions and global export regulations and work to ensure that the products they make or distribute are not diverted to prohibited users. Mouser did not respond to requests for comment.

The documents do not suggest that any Western company directly supplied Iran or Russia with components used in production of the drone.

In response to questions from The Post, the White House said U.S. officials have worked to prevent Moscow from obtaining technology that might be used in its war against Ukraine and have imposed sanctions against those involved in the transfer of Iranian military equipment to Russia.

“As Russia searches for ways to evade our actions, the U.S. government, alongside allies and partners, will continue to ramp up our own efforts to counter such evasion,” Adrienne Watson, a spokeswoman for the National Security Council, said in a statement.

According to a breakdown of material requirements along with the status of negotiations with suppliers, Alabuga specialists were able to promptly source the materials required for manufacturing the airframe. Most of those components are supplied by Russian or Belarusian companies, and the Chinese company Metastar provided a sample of a material used to make the wings, the breakdown shows.

Other components proved harder to obtain. Documents highlighted a problem that perpetually plagues Russian military production: the lack of a capable domestic engine industry. The Shahed-136 is powered by a reverse-engineered German Limbach Flugmotoren L550E engine, which Iran illicitly obtained two decades ago.

To reach the final stage of the project, Russia would have to come up with its own version of the engine, which engineers described in internal documents as their most complex task. A spreadsheet created by a senior engineer on Nov. 5, titled “Questions asked to Iran at the very beginning of cooperation,” listed a request for a copy of the engine as “the most important point.”

“Better two: one to take apart, and after the chemical analysis it will not be functional; the second one is for comparative tests. The propeller is also needed for testing,” the engineer wrote. “We’ll copy it too.”

The questions — over 120 in total — were separated into thematic categories that include “policy” and “warhead,” and requested details on how Iran achieved mass production. They also asked “which countries are suppliers of electronic components.” The documents obtained by The Post do not show a response to that question.

The Alabuga team also requested a meeting with Mado, an Iranian company that produces engines and other components for UAVs with the help of illicitly obtained Western technology. Western governments imposed sanctions on the company late last year for its contribution to the war in Ukraine.

Subsequent documents include a detailed description of the re-engineered Limbach engine, known as the Mado MD550. The authors indicated that the description was compiled on the basis of the information “provided by Mado specialists.”

Efforts to reach Mado for comment were not successful.

Despite those challenges, Alabuga engineers have worked to improve the drones, the documents show. They have swapped out malfunctioning Chinese electronic components for more-reliable analogues, and they replaced a glue the Russians deemed defective and added waterproofing in a design overhaul of the airframe.

Struggling to staff up

Documents show that Alabuga has struggled to fill specialized positions at the facility, which was to have 810 employees for each of three shifts per day. The production team lacked experts in key and highly complex areas of drone development including electronic warfare systems.

Numerous Alabuga employees have traveled to drone manufacturing centers in Iran to gain expertise, according to personnel documents. Delegations included project managers and engineers, along with students and manual laborers.

While one group was visiting Tehran on Jan. 29, Israeli’s external intelligence service, the Mossad, carried out a strike on a weapons factory in the Iranian city of Isfahan, leaving flames billowing from a site believed to be a production hub for drones and missiles. Alabuga’s managers and engineers were forbidden to leave their hotel as Iranian officials worried that Israel might strike facilities the group was supposed to tour, according to the individual who provided the documents.

The documents also reveal that Central Asian workers who held low-level jobs at Alabuga were sent to Iran because they speak a language similar to Farsi. They were supposed to observe the assembly process on Iranian production sites, interpret for the rest of the delegation and undergo training that would allow them to build drones back in Russia.

By end of spring, an estimated 200 employees and 100 students had received training at the Iranian facilities, according to the documents and the individual.

Students from the local polytechnic university were required to work at the Alabuga factory as part of their curriculum, the Russian news outlet Razvorot reported in July.

Alabuga also has sought to recruit young people for menial assembly-line positions, with glitzy ads promising “a career of the future” and subsidized housing. One ad posted on Alabuga’s Telegram channels invites women ages 16 to 22 to relocate to the site and “build a promising career in the largest center for training specialists in the UAV production,” with a wage starting at $550 a month.

At the same time, the individual said, some workers have been uncomfortable with the idea of developing drones to pummel Ukraine and discontented by what they view as long work hours and poor management. To keep staffers and lure talent from rival manufacturers, Alabuga boosted salaries, budget documents show, with some key workers earning 10 times the median Russian salary. Management created obstacles to prevent employees from quitting, including seizing passports and requiring workers to seek sign-off before leaving their positions, according to the individual.

Damaged drones

The Russians had issues in dealing with the Iranian side. An estimated 25 percent of the drones shipped from Iran for Alabuga’s use and delivered by Russian Defense Ministry aircraft were damaged, according to the documents and the individual who provided them.

One document from February includes a log of damaged or faulty drones received in a second shipment of the UAVs from Iran — separated into the categories of “big boats” and “small boats,” which refer to the Shahed-136 and the Shahed-131, respectively, despite Alabuga’s mainly being interested in the former. The document indicates that 12 of the Iranian drones in the Feb. 15 delivery were inoperable, including one irreparably damaged when it was dropped on the ground.

“That was an interesting moment, because the initial agreement with Iran concerned only big Shahed drones, as the smaller 131 model is pretty useless — its payload is ten times lower compared to the 136 model, and it can maybe blow up a car,” the individual said. “But as you can see, Iran pressed its own conditions for the deal and supplied smaller models, many of them broken.”

The log shows that the Russian team lacked the expertise and replacement parts to repair the damaged or malfunctioning drones.

The team struggled to meet initial deadlines. A February memo shows that project managers warned their higher-ups about a 37-day delay in the schedule as communications with Iran were slowed by the Russian Defense Ministry’s bureaucracy and Iran’s failure to provide some technical documentation.

“Iranians aren’t used to working according to some high European standards, and I suspect they didn’t have a ready set of all documentation,” the person said.

Technicians suggested reverse-engineering a drone already in the possession of Russia’s Defense Ministry to create their own project documentation, but the request was denied as their managers feared it would be perceived as a failure on Alabuga’s part by military officials in Moscow, according to the individual.

“There was a political moment that if we say that we don’t have something, it would show our weakness and inability to implement such a complex project, so all problems were being swept under the rug,” the individual said.

Delivery of the drones and equipment to the production facility also was a challenge. The first Iranian shipments arrived at Begishevo Airport in Tatarstan with little advance notice. Staffers at Alabuga scrambled to sort out the basic logistics of transporting the cargo back to their warehouse, the individual said.

In one instance, after securing trucks to transport the shipment, the staffers realized they did not have a forklift to load the heavy wooden crates full of disassembled drones. An employee was dispatched to a nearby business to find an off-loader, only to realize after finding one that no one was qualified to operate it.

The individual related that boxes of drones were first stored in a nearly empty warehouse as the facility was not yet prepared even for simple tasks such as reattaching parts of the UAV body that had been disassembled for transportation.

“So they just unboxed them and tried to reassemble on the floor,” the individual added. “At the same time, they wanted to show the Defense Ministry that the process was ongoing, the facilities are being built, so they bought some tables and did a photo shoot to show how they are supposedly actively assembling these drones.”

High-ranking officials at Alabuga spent a week taking and retaking photos, according to the individual.

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/archetype/TW52OPBYSVEAXEDH4ATQWIVMVI.jpg)

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/archetype/XSAL3RNFONF7ZAOISMC2R2LGGY.jpg)