Gokul Ganesh

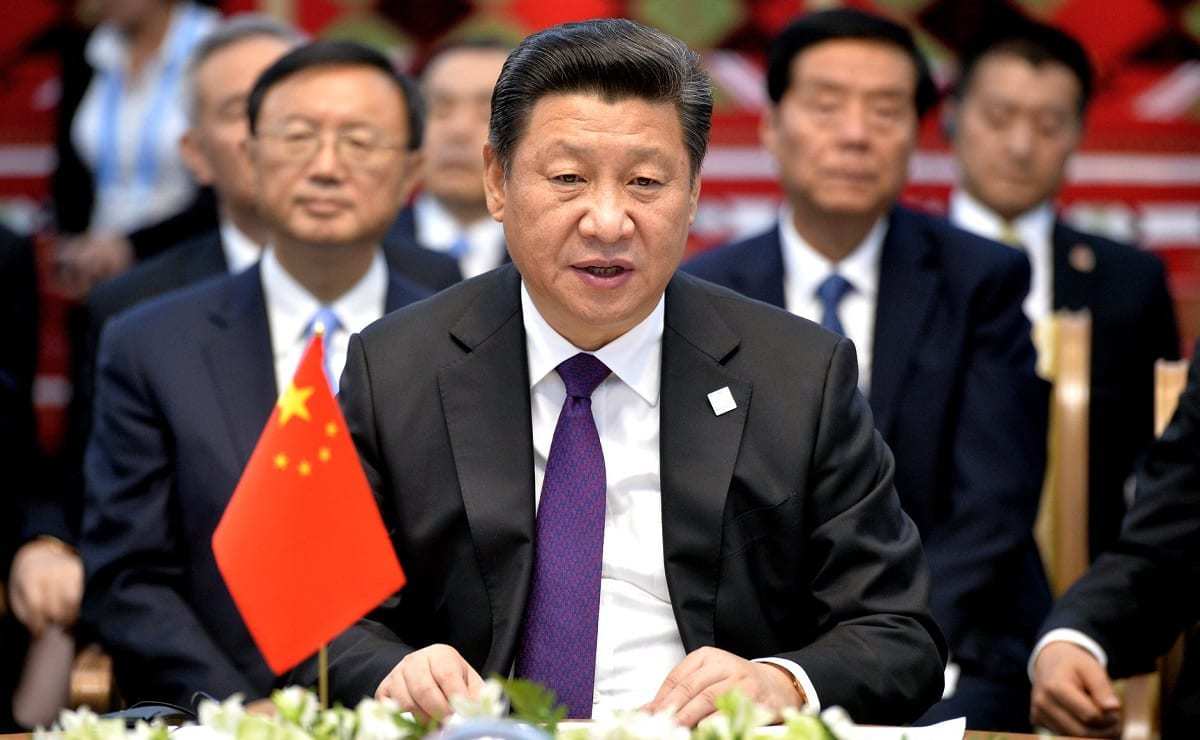

In the global chessboard of geopolitics, rare earth elements (REEs) are the new power pieces. Their strategic importance continues to escalate, especially for nations like India with a burgeoning technology sector. This is underscored by the Indian government’s recent unveiling of a list of 30 critical minerals integral to national security and active efforts to establish a domestic semiconductor manufacturing plant. Essential to hi-tech and renewable energy industries, REEs’ dominance by China—which controls over 80-90% of the global market—poses a significant challenge, leaving nations like India in an uncomfortable position of dependence on their eastern neighbor.

Africa – the sleeping giant of REE reserves – remains largely underexplored. Its rich REE deposits in countries like Burundi and Tanzania wait in the wings due to lack of technology and investment. However, the narrative is rapidly changing with China weaving its intricate web of influence in Africa’s REE sector. Yet China’s largesse comes with a price. Its notorious “debt-trap diplomacy” ensnares economically vulnerable nations into an unending cycle of debt, exemplified by Zambia, Djibouti, and Angola.

In stark contrast to China, India has always aimed to pursue a non-extractive and sustainable approach in all its engagements. India’s External Affairs Minister, S. Jaishankar, recently reaffirmed India’s non-expansionist and inclusive approach towards Africa. Thus, India, not China, at least over the longer term, clearly emerges as the preferred partner for Africa, setting the stage for a strategic repositioning of India’s influence in the continent.

The Winning Factor

An underappreciated facet of India’s connection with Africa is the vibrant Indian diaspora, which numbers over 3 million. Integrated into Africa’s socioeconomic fabric, the Indian diaspora has proven its mettle in the trade, manufacturing, and services sectors. This network, with its deep-rooted ties and understanding of local contexts, could be the catalyst for India’s enhanced engagement with the African REE sector.