Susan B. Glasser

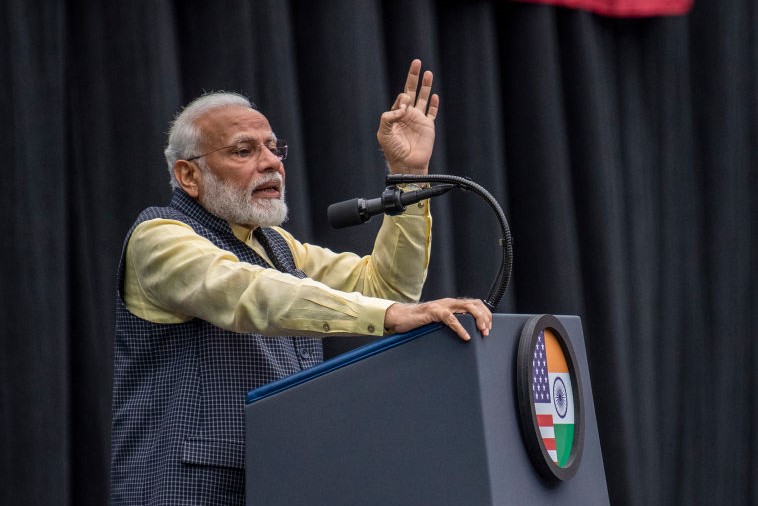

Modi’s visit has called attention to his autocratic leanings at home and served as a reminder of the trade-offs inherent in Biden’s foreign policy.

Just before 2 p.m. on Thursday, President Joe Biden and the visiting Prime Minister of India, Narendra Modi, stepped before a crowd of journalists in the White House’s East Room for one of the rituals of an official state visit to Washington: the press conference. The event was presented in the official schedule merely as an opportunity to “take questions”—apparently because of Modi’s persistent refusal to actually hold a press conference—and the questions, in the end, were also limited to just one U.S. and one Indian journalist. Both leaders swatted away the inevitable queries about India’s democratic backsliding with canned riffs about the shared importance of “democratic values,” as Biden somewhat gingerly put it, and the democracy that “runs in our veins,” as Modi sanctimoniously explained.

The choreographed exchange seemed most newsworthy in underscoring Biden’s willingness to suffer whatever embarrassment it entailed in the name of geostrategic positioning. Modi’s visit has, predictably, called attention to his autocratic leanings at home and served as a reminder of the trade-offs inherent in Biden’s foreign policy. The former U.S. diplomat Aaron David Miller called Biden’s embrace of Modi and the human-rights-abusing Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, whom Biden visited last year despite having vowed as a candidate to shun and isolate him, “a head-exploding hypocritical pivot.” Other criticisms, including from members of Biden’s own party, who planned to skip a scheduled Modi address to a joint session of Congress, have been equally scathing. Administration officials, meanwhile, are left to wonder just how exactly they are supposed to help Ukraine win the war or successfully contain China without forging closer ties with India.

As a practical matter, though, it’s far from clear whether the accommodations to Modi were worth it. In his White House remarks, Modi offered no sign of softening on the matter of support for Ukraine. He did not even acknowledge that it was Russia that started the war. He definitely did not sound like he had signed up for charter membership in Biden’s oft-cited alliance of democracies versus autocracies at this dangerous inflection point in world history.

/https%3A%2F%2Fengelsbergideas.com%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2023%2F06%2FLi-Qiang-Germany-visit.jpg)