Husain Haqqani

Pakistan is adrift in a sea of troubles. Its economy is in a tailspin. GDP growth in the past year shriveled to only 0.29 percent. Annual inflation has soared to 36 percent, and annual inflation in food prices stands at a whopping 48 percent. The country faces a balance-of-payments crisis, and negotiations with the International Monetary Fund over a bailout have stalled. Catastrophic floods in 2022 have forced the country, until recently a wheat exporter, to import wheat.

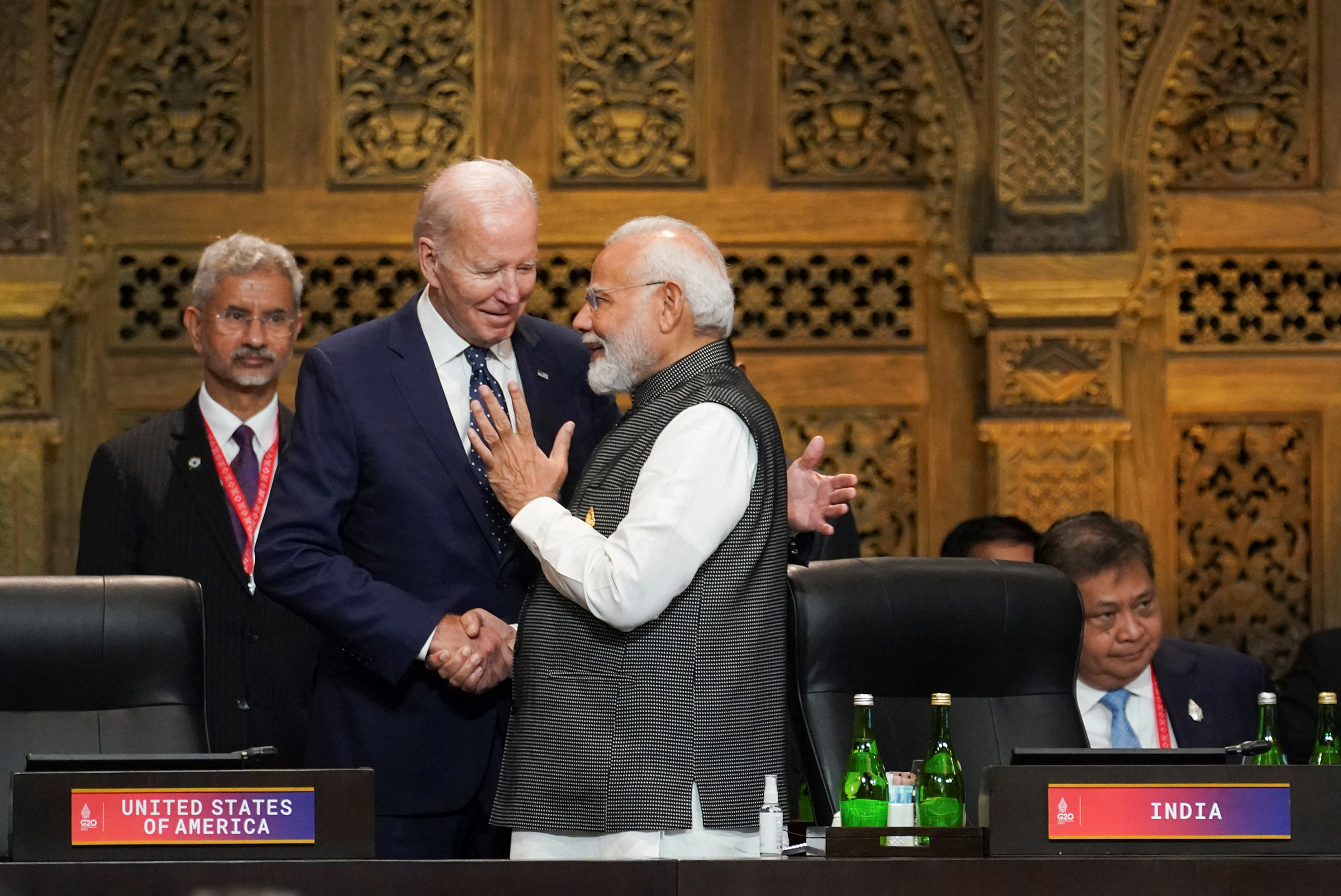

Compounding the economic misery is the ongoing security threat posed by the Pakistani Taliban, a militant group that has grown increasingly brazen in its attacks on civilian and military targets across the country. Internationally, Pakistan’s standing is at an all-time low. Relations with the United States, once an ally and the source of billions of dollars in military and economic assistance, have waned since the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan in 2021. India, a rival ever since the two countries emerged from the partition of British India in 1947, refuses to engage its neighbor until Pakistan acknowledges its role in backing terrorism across the border and clamps down on militants. Even traditional partners and friends, including China and countries in the Arab and Islamic world, seem weary of Pakistan’s metastasizing crises.

But in the last year, these myriad woes have been driven to the margins by the crisis occupying center stage, a political drama that has convulsed the whole country. Since the spring of 2022, Pakistani politics have been gripped by the struggle between Imran Khan—the populist former prime minister who was ousted by a parliamentary vote of no confidence last year—the country’s powerful military, and the ruling civilian political parties.

Khan once enjoyed the backing of the army, which helped steer him to power in 2018, but he fell out of favor and tumbled out of power in 2022. Ever since, he has led rallies and marches across the country, blaming the United States for conspiring to remove him from office, decrying the government that replaced his, and denouncing senior military commanders. The situation came to a head on May 9, when Khan was arrested on corruption charges, an event that sent his supporters into the streets. Mobs attacked the army headquarters and several military installations, precipitating a crackdown. Khan’s followers have been arrested en masse, and many leaders of his party have quit, some under pressure from the military. It seems unlikely that Khan’s challenge to the ruling establishment will ever be able to regain the strength it once seemed to possess. Khan, often lampooned as a populist hothead, fought for himself more than for democracy, and his orchestration of violence to demonstrate his popularity could precipitate his defeat by the army. Instead of safeguarding Pakistan’s fragile democracy, Khan’s refusal to compromise with other civilian parties has added to the abiding strength of the generals and the tenacity of their grip on the country.

THE WRATH OF KHAN

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/archetype/35CAA3IBNFAILJZ3XUEQ6W2ODM.jpg)