BRAHMA CHELLANEY

NEW DELHI – No bilateral relationship has deepened and strengthened more rapidly over the last two decades than the one between the United States and India. In fact, Narendra Modi’s upcoming visit to the US will be his eighth as India’s prime minister, and his second since US President Joe Biden took office. The US has at least as much to gain from the growing closeness as India does.

NEW DELHI – No bilateral relationship has deepened and strengthened more rapidly over the last two decades than the one between the United States and India. In fact, Narendra Modi’s upcoming visit to the US will be his eighth as India’s prime minister, and his second since US President Joe Biden took office. The US has at least as much to gain from the growing closeness as India does.India just overtook China in population size, and although its economy remains smaller, it is growing faster. In fact, India is now the world’s fastest-growing major economy, with GDP having already surpassed that of the United Kingdom and on track to overtake that of Germany. India thus represents a major export market for the US, including for weapons.

But commercial opportunities are just the beginning. In an era of sharpening geopolitical competition, the US is seeking partners to help it counter the growing influence – and assertiveness – of China (and its increasingly close ally Russia). India is an obvious partner for its fellow democracies in the West, though what it really represents is a critical “swing state” in the struggle to shape the future of the Indo-Pacific and the world order more broadly. The US cannot afford for it to swing toward the emerging Russia-China alliance.

Consider America’s quest to bolster supply-chain resilience through so-called friend-shoring. As Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen has explained, India is among the “trusted trading partners” with which the US is “proactively deepening economic integration,” as it attempts to diversify its trade “away from countries that present geopolitical and security risks” to its supply chain.

India is also integral to maintaining peace and stability in the Indo-Pacific. Its military standoff with China – now entering its 38th month – is a case in point. By refusing to back down, India is openly challenging Chinese expansionism, while making it more difficult for China to make a move on Taiwan. Biden has not commented on the confrontation, but he is certainly paying attention. It is telling that both Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin and National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan visited New Delhi this month.

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/archetype/PG633SY5DZBXPES5IHVDXFHW34.jpg)

USAF KC-46 Pegasus refueling aircraft refuels a C-17 Globemaster III during a test flight July 12, 2016 (U.S. Air Force photo)

USAF KC-46 Pegasus refueling aircraft refuels a C-17 Globemaster III during a test flight July 12, 2016 (U.S. Air Force photo):quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/archetype/35CAA3IBNFAILJZ3XUEQ6W2ODM.jpg)

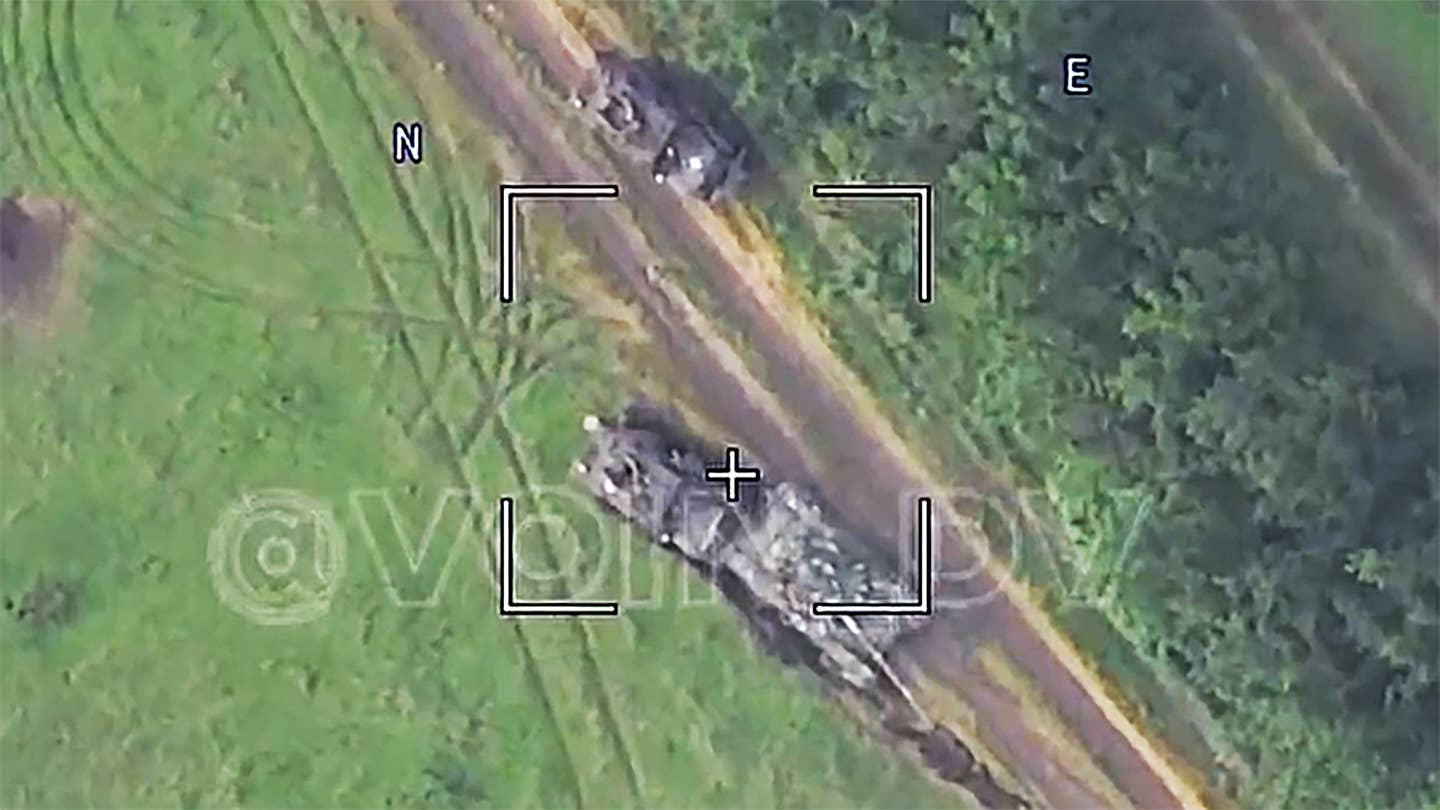

A Russian Lancet loitering munition is about to hit the Ukrainian T-72 tank. (VOIN DV video screencap)

A Russian Lancet loitering munition is about to hit the Ukrainian T-72 tank. (VOIN DV video screencap)