Simone McCarthy

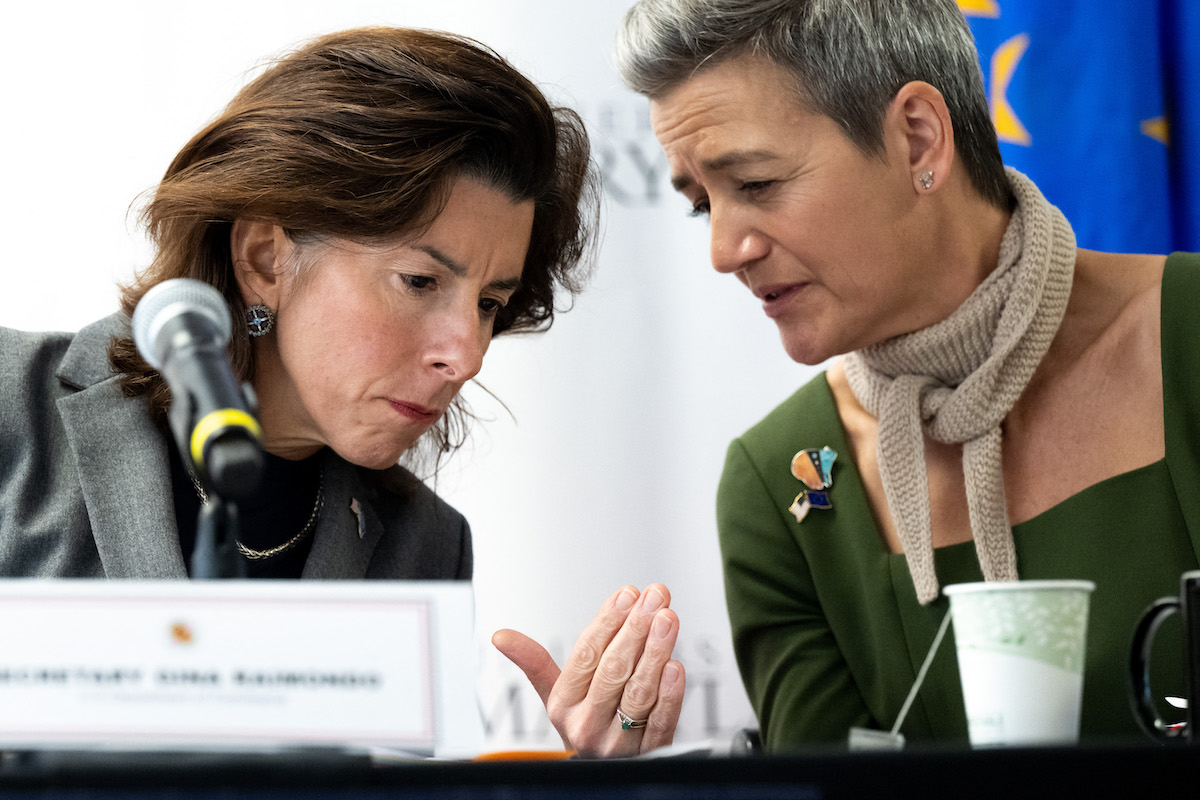

Members of the media wait ahead of the unveiling of the Communist Party of China's new Politburo Standing Committee at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, China, on Sunday, Oct. 23, 2022.

India and China are fast heading toward having few or no accredited journalists on the ground in each other’s country – the latest sign of fraying relations between the world’s two most populous nations.

New Delhi on Friday called on Chinese authorities to “facilitate the continued presence” of Indian journalists working and reporting in the country and said the two sides “remain in touch” on the issue.

Three of the four journalists from major Indian publications based in China this year have had their credentials revoked by Beijing since April, a person within India’s media with first-hand knowledge told CNN.

Meanwhile, Beijing last week said there was only one remaining Chinese reporter in India due to the country’s “unfair and discriminatory treatment” of its reporters, and that reporter’s visa had yet to be renewed.

“The Chinese side has no choice but to take appropriate counter-measures,” Foreign Ministry spokesperson Mao Ning said at a regular briefing when asked about an article on the recent ejections of journalists in the Wall Street Journal, which first reported the story.

The situation is the latest flashpoint in the fractious relationship between the nuclear-armed neighbors, which has deteriorated in recent years amid rising nationalism in both countries and volatility at their contested border.

The reduction of journalists – which includes both those from China’s government-run state media and major Indian outlets – is likely to further degrade those ties and each country’s insight into the other’s political and social circumstances, at a time when there is little room for misunderstandings.

/https%3A%2F%2Fengelsbergideas.com%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2023%2F06%2FDnieper-dam.jpg)