NILESH CHRISTOPHER

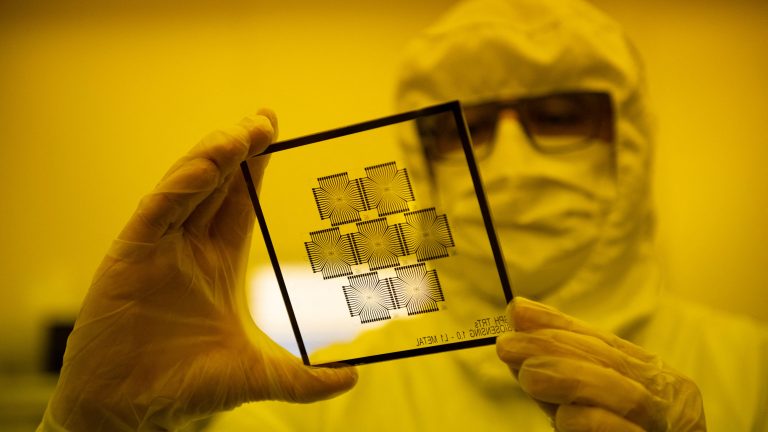

In December 2021, as the world struggled with the Covid-19 pandemic, the tech sector faced an unanticipated challenge: an acute shortage of semiconductor chips. Taiwan is the world leader in semiconductor chip manufacturing, and the pandemic-triggered lockdowns increased delivery times for the chips. This walloped the production of everything, from cars to mobile phones.

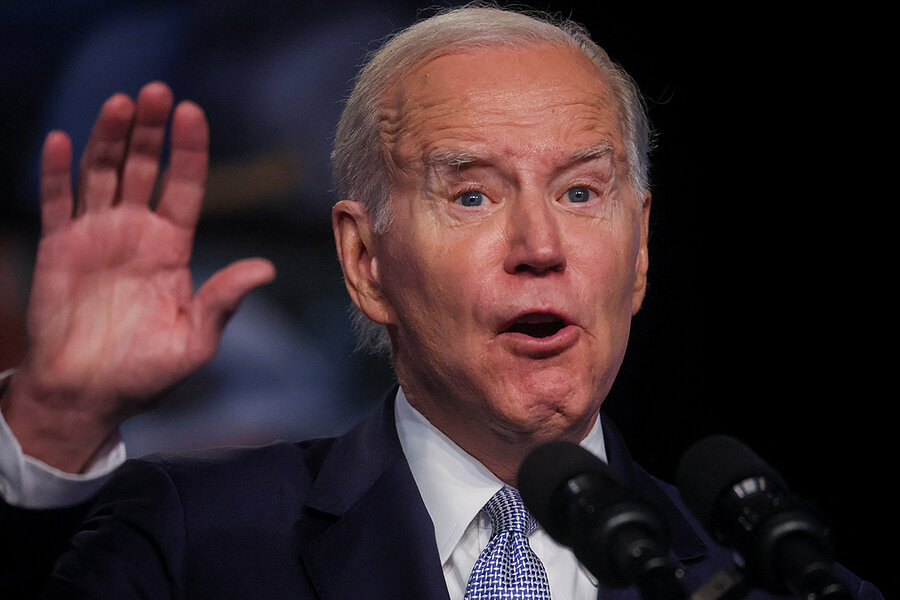

In December 2021, as the world struggled with the Covid-19 pandemic, the tech sector faced an unanticipated challenge: an acute shortage of semiconductor chips. Taiwan is the world leader in semiconductor chip manufacturing, and the pandemic-triggered lockdowns increased delivery times for the chips. This walloped the production of everything, from cars to mobile phones.Now, even as the pandemic-related bottlenecks have eased, conversations around semiconductor chips — tiny circuits that manage the flow of electric current in equipment and devices — refuse to go away. Semiconductors have, in fact, become a major geopolitical issue. They are at the heart of the ongoing trade war between Washington and Beijing, as the U.S. has banned the supply of advanced chip-making software to China.

Meanwhile, India has made an ambitious push to position itself as an alternative to China, announcing a $10-billion incentive plan to boost semiconductor manufacturing in the country. Indian prime minister Narendra Modi’s goal of establishing India as a semiconductor manufacturing hub is still a work in progress. Over the past two decades, India has had two failed attempts to build semiconductor plants. The moment might pass in 2023, too, if the country doesn’t recognize its potential.

Rest of World met Pranay Kotasthane, chair of the High-Tech Geopolitics Programme at Takshashila Institution, a nonpartisan, nonprofit think tank based in Bengaluru, to talk about what the U.S.-China chip war means for India. His latest book Missing in Action looks at public policymaking in India and why the state functions the way it does. During the interview, Kotasthane talks about how chips became geopolitical flashpoints and the jumbled priorities of India’s semiconductor policy.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

How did semiconductors become a geopolitical issue?