KONARK BHANDARI

For all the talk about U.S.-China decoupling and its implications for the currently rickety narrative of globalization, recent years have demonstrated that reports about the looming demise of globalization are exaggerated. Instead, a recalibration is underway of the long-prevailing terms on which globalization had played out and that were fundamentally premised on just-in-time supply chains.

A lot of the discussions on what globalization will look like in the future revolve around companies operating in multiple jurisdictions shifting their supply chains to other countries as a part of the process of global value chain diversification. It is here that experts have spoken about India possibly entering the fray as a candidate for where these supply chains can be relocated. This is the second-order effect of supply chain fragmentation—a scenario where India must jockey with other countries that seek to onshore such supply chains.

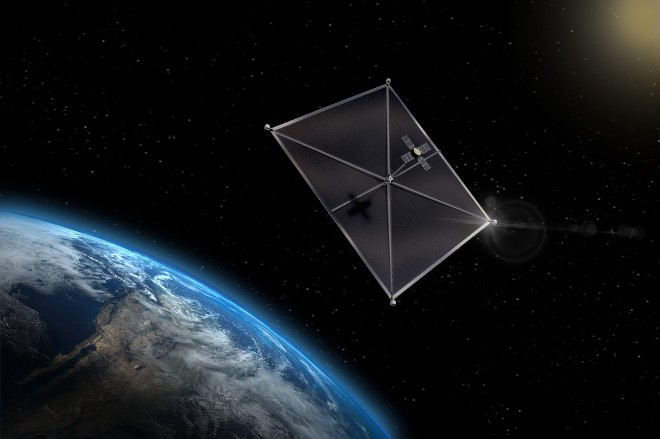

While India has positioned itself admirably to benefit from the fractious nature of the U.S.-China relationship, most of the onshoring to India has been in the form of consumer technology products like mobile handsets and solar energy equipment. What is missing from the picture is a focus on cutting-edge high-technology items like semiconductors, high-performance computing, and commercial space technology.

These sectors are significant for India as it starts to take an unprecedented interest in developing its high-technology sectors. Key members of the present government have also realized that a long-standing proclivity for a service-sector-led economy—India’s engine of growth—is simply not feasible at a time when India seeks to advocate for and transition to a more vigorous industrial base. It is here that a U.S.-India high-technology partnership assumes significance. However, U.S. export controls, specifically those under a regime called the International Traffic in Arms Regulations (the ITAR), may need to be carefully considered before this partnership can deliver.

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/archetype/DEVA362EX5FJLDBUN7CLIFI5WU.jpg)