Hemant Waje

Union Minister Jitendra Singh on Saturday said Pakistan is habitual of making unnecessary noises alleging violations of the Indus Waters Treaty (IWT), even though there has been none and India has always stood by its end of the pact.

The statement of the Minister of State in the Prime Minister's office comes on the heels of India issuing a notice to Pakistan seeking a review and modification of the IWT in view of Islamabad's "intransigence" in complying with the dispute redressal mechanism of the pact that was inked over six decades ago for sharing of waters of cross-border rivers.

The step comes around 10 months after the World Bank announced appointing a neutral expert and a chair of the Court of Arbitration under two separate processes to resolve the differences over the Kishenganga and Ratle Hydro Electric Projects following Islamabad's refusal to address the matter through bilateral talks.

"IWT has a long history after it was signed in 1960, giving control of three rivers each to India and Pakistan. While Jhelum, Chenab and Indus were given to Pakistan, India was given the control of Ravi, Beas, and Sutlej.

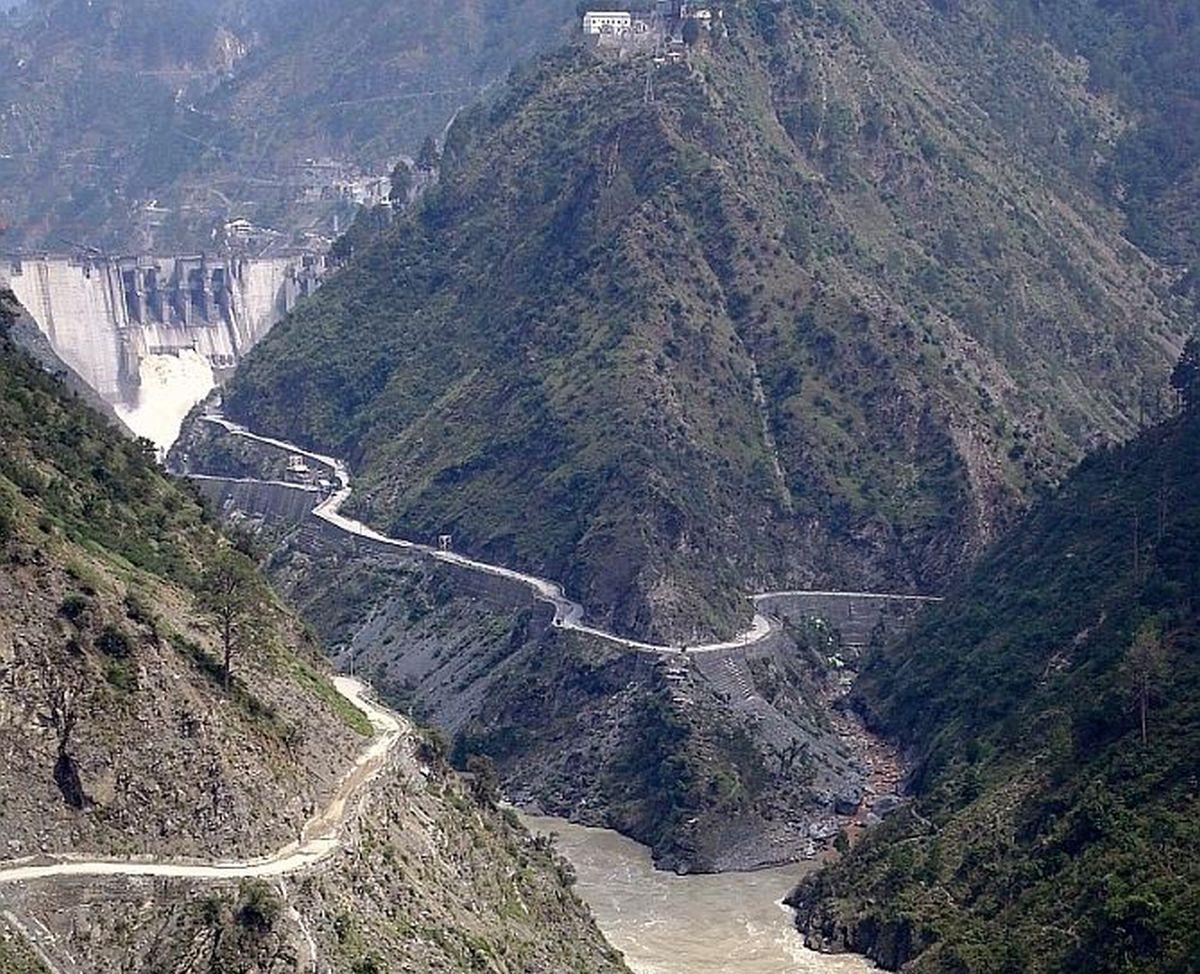

"The first phase of Shahpur Kandi dam project on river Ravi is nearing completion. The project was in limbo for the last 40 years and our share of water was also flowing across the border.

"Similarly, the Ratle project in Kishtwar over Chenab was abandoned for eight years and the work on it started only last year under joint venture between the Centre and the UT administration," Singh told reporters on the sidelines of a function in Kathua district.

He said Pakistan has raised an objection and is claiming violation of the IWT but India's position is strong as there was no violation and the waters are allowed to flow into Pakistan as per the agreement, despite construction of dams and other projects.

:quality(100)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thesummit/CHWQOO5WYFCYRPHVK57Q4LABEU.jpg)

:quality(100)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thesummit/I55MMFEBYZESDGQM7I6OMPNIUM.jpg)

Ukrainian troops fire a howitzer in the Zaporizhzhia Region in December 2022.Dmytro Smoliyenko / Ukrinform/Future Publishing via Getty Images

Ukrainian troops fire a howitzer in the Zaporizhzhia Region in December 2022.Dmytro Smoliyenko / Ukrinform/Future Publishing via Getty Images