Jagannath Panda and Choong Yong Ahn

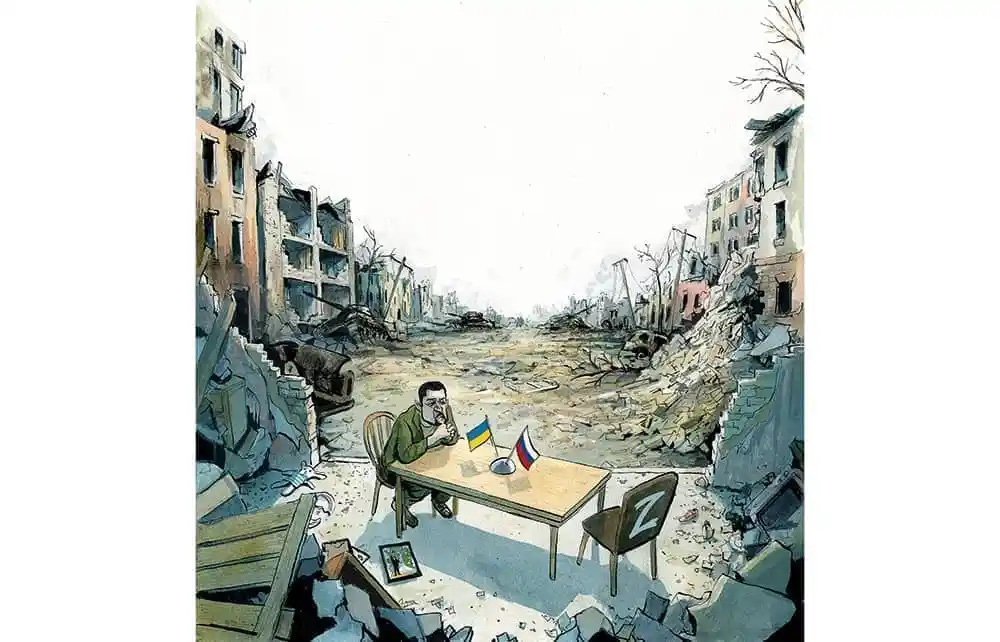

Then-South Korean President Moon Jae-in (left) walks with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi during a state visit to New Delhi, India, July 10, 2018.Credit: Cheong Wa Dae

The launch of South Korea’s first Indo-Pacific vision document, namely the “Strategy for a Free, Peaceful and Prosperous Indo-Pacific,” in December 2022 by the Yoon Suk-yeol administration has raised expectations for enhanced momentum in South Korea’s strategic ties with a rising India – arguably, one of the most significant “like-minded” partners in the region. This heralds a significant break from the long-prevalent worldview in Seoul that sidelined most states other than the United States, China, Japan, and Russia, considered key players in Northeast Asian politics.

Looking back, the previous South Korean administrations’ cautious approach to strategic alignments gave deference to Seoul’s largest trade partner, China, and allowed it significant leeway while cozying with South Korea’s security treaty ally, the United States. The China dilemma for Seoul, which exists for other Asian states – namely the strategic hedging required to manage both the United States and China – became starker after the escalating China-U.S. hostilities arising from the Donald Trump administration.

China’s economic and psychological backlash targeting South Korea after the deployment of the U.S. Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) missile defense system forced then-South Korean President Moon Jae-in to reassess strategic priorities. Among other initiatives, Moon introduced his New Southern Policy (NSP; later rebranded the NSP Plus) while pushing for simultaneously a New Northern Policy embracing more of Russia and Central Asia. In both cases, the goal was to shift some of Seoul’s focus away from the major powers into other regions, primarily Southeast Asia and India, in order to diversify South Korea’’s economic and strategic ties.

Considering Moon’s inordinate focus on the Korean Peninsula peace process and the NSP’s emphasis on trade and investment, bypassing strategic concerns, the NSP (Plus) did not deliver the promised South Korean resurgence in the target regions. Moon did inch toward alignment with the U.S. “free and open Indo-Pacific” (FOIP) vision via the NSP, yet overall the projected ambiguity overshadowed South Korea’s economic as well as middle power potential. This prevented Seoul from realizing its geopolitical ambitions à la Modi’s India.

:quality(100)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/thesummit/F2YOJ3CUUBFVRFXJYPYFW7JCBQ.jpg)