Nara Sritharan

Kritika Jothishankar

Sarah Wozniak

Chinese and Indian interest in Nepal’s immense hydropower potential has made it a focal point of geopolitical competition.

Political instability, bureaucratic red tape, and underdeveloped infrastructure prevent Nepal from harnessing its hydropower potential.

The United States should closely monitor the geopolitical maneuvering between China and India in Nepal’s hydropower sector to balance its regional interests and support Nepal’s development goals.

Nepal’s geographical and topographical attributes have endowed it with a newfound significance in the foreign policy realm, where nations strategically pursue power and influence. This significance is particularly pronounced in hydropower development, where the confluence of ambitions between China and India has transformed Nepal into a focal point of their intricate power play. Regarding geography and geopolitics, Nepal occupies a hazardous place on the map. The country sits where the Indian subcontinent meets the mighty Himalayas, leaving it subject to frequent earthquakes. At the same time, Nepal remains uncomfortably poised between Asia’s two leading powers, China and India. The longtime diplomatic rivalry between Beijing and New Delhi for political influence in Nepal now has a new focus—the country’s hydropower sector.

Image 1: Map of Nepal

Source: Map shows Nepal (highlighted in green) nestled between India and China. Map created by Narayani Sritharan.

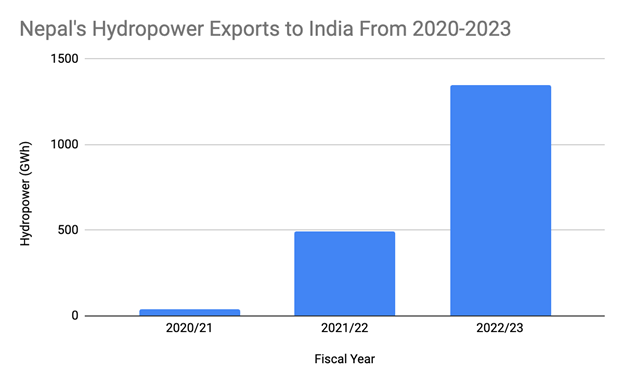

Nepal endows immense hydropower potential with its 6,000 rivers. According to our interviewed policymakers and recent studies, Nepal’s hydropower potential is 42,000 megawatts (MW). Its rivers hold the promise of a substantial energy source that could address the country’s own energy needs and create a surplus for export. In 2023, the hydropower sector produced 10,536 GWh, of which 9,358 GWh was consumed domestically, 1,346 GWh was exported to India, and 1,665 GWh was a wasted surplus. This potential has prompted both China and India to view Nepal’s hydropower resources as a means to secure their respective energy futures, shape regional dynamics, and assert dominance.

During this investigation, we conducted qualitative interviews with a wide range of policymakers and stakeholders, gaining invaluable insights into the intricacies of Nepal’s hydropower development landscape. These interviews not only shed light on the nuanced perspectives, concerns, and aspirations of key actors actively shaping Nepal’s hydropower policy, but also highlighted the geopolitical competition between China and India for Nepal’s hydropower potential. The United States should closely monitor these dynamics to balance its regional interests and support Nepal’s development goals, considering the challenges uncovered in our interviews, such as political instability, bureaucratic red tape and underdeveloped infrastructure.

Geopolitical Interests in Nepal’s Hydropower Sector

With its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) extending across continents, China views Nepal’s hydropower sector as a crucial link in its grand vision of connectivity and economic expansion. Through strategic investments and infrastructure projects, China seeks to deepen its influence in Nepal, fostering cross-border energy networks that could connect Nepal’s rivers to the energy-hungry markets of China’s western provinces.

Meanwhile, India, Nepal’s neighbor with strong historical, cultural, and economic ties, has also recognized the strategic significance of Nepal’s hydropower potential. Leveraging its proximity and longstanding partnership with Nepal, India seeks to pursue joint hydropower projects that could alleviate Nepal’s energy shortages and foster stronger regional integration.

Image 2: Kulekhani Reservoir and High Dam pictured by Sarah Wozniak

Source: Photo by Sarah Wozniak

For many in Nepal, and certainly among the policymakers and stakeholders we spoke to, the economic future of Nepal hinges on hydropower development. As one interviewee passionately emphasized, “Nepal can make money out of exporting hydropower is what Saudi Arabia can make selling oil. So, it’s a huge potential.” However, among plenty of run-of-the-river projects financed predominantly by the Nepali private sector, there is only one high-dam associated with a reservoir, the Kulekhani Dam. The common response we received when inquiring about the scarcity of reservoirs for off-peak water storage was that high dam projects are prohibitively costly and carry substantial risks, making them unattractive to the private sector. Therefore, according to the majority of our interviewees, the government needs to do it, but they do not have the money or capacity to undertake such big infrastructure projects. The Kulekhani Dam was financed by the World Bank, the Kuwait Fund, the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) Fund, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), and the Overseas Economic Cooperation Fund (OECF) of Japan and the Nepalese government. Apart from this example, foreign donors have not made any sizable investment commitments. Political instability and red tape were often-cited explanations for the lack of additional investments in high dams in Nepal.

Political Instability

Nepal’s persistent political instability has significantly affected its business environment and regulatory consistency. The decade-long civil war, from 1996 to 2006, between the government and the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist) stemmed from socioeconomic disparities and governance challenges. In 2008, Nepal transitioned into a federal democratic republic, abolishing the monarchy, and electing a Constituent Assembly to draft a new constitution in 2015. This momentous transition heralded a new chapter in Nepal’s political history, steering the nation towards uncharted waters. Since 2008, the country has witnessed various political shifts and coalition governments, reflecting an ongoing process of adaptation and transformation in its political landscape.

Red Tape

Nepal’s hydropower sector grapples with frequent policy alterations, legal shifts, and regulatory unpredictability. The project approval journey necessitates engagement with numerous government bodies at various administrative tiers, culminating in vexing delays and coordination bottlenecks. Foreign investors encounter a convoluted bureaucratic landscape when seeking essential permits and approvals, breeding uncertainty, as the experts we communicated with attest. Additionally, Nepal’s underdeveloped infrastructure—notably its road networks, transmission lines, and power grids—compound logistical hurdles, driving up expenses associated with hydropower ventures. These challenges collectively present formidable barriers to Nepal’s aspirations in the hydropower arena.

Geopolitics Between India and China

Nepal faces an additional challenge of navigating India and China’s geopolitical rivalry. Both powers assert their influence in Nepal through infrastructure investment and the hydropower sector is one prime example. In recent years, India has scaled up hydropower imports and investment in Nepal’s hydropower sector due to its growing demands for energy and water, as well as motivations to counter China’s presence. According to the Nepal Electricity Authority’s annual report for 2022–2023, Nepal’s total export to India soared to 1,346 GWh in FY 2022–2023 compared to the previous year’s 493 GWh. China has yet to import electricity from Nepal due to the technological challenge of constructing transmission lines across the Himalayan border. Additionally, in May 2023, India secured ten contracts to operate hydropower plants in Nepal, surpassing China’s allocation of just five contracts. As Nepal’s only large importer of hydropower, India is increasing its control over the sector as Nepal becomes eager to utilize its 42,000 megawatts of hydroelectric resource potential.

Image 3: Nepal’s Hydropower Exports to India

India’s Growing Interest in Nepal’s Hydropower Resources

While India makes strides by gaining new project contracts and establishing long-term power trade agreements, many experts view this trend as threatening Nepal’s resource ownership and political relations with neighboring countries. Some hold passionate opinions on the subject, with one expert expressing, “Exporting all of the energy [to India] and depriving the economy of Nepal is colonization.” A reason for this extreme rhetoric seems to stem from Nepal officials’ dissatisfaction with the pricing system where the Indian private sector buys Nepalese power through a bidding system, resulting in Nepal earning less. To rectify this disadvantage, the Nepal Electricity Authority now trades electricity in the day-ahead market, allowing greater price flexibility.

Additionally, experts expressed their opinion about the intentional inefficiency of Indian dam development—Indian companies stall construction to maintain long-term ownership of dams in Nepal, especially in border areas where India claims Nepalese rivers and hydropower dams as their own. Nepal’s southern neighbor has delayed signing negotiated hydropower trade agreements, causing Nepalis to fear that India will not follow through with its promises.

The common narrative around India’s “big brother” presence in Nepal is rooted in past political tensions. India has always favored a more democratic Nepal to maintain stability and has asserted this position through micromanagement in Nepal’s politics. For instance, India seemingly supported ethnic protests against Nepal’s 2015 constitution and imposed an unofficial blockade of the border. These actions hurt Nepal’s economy by halting oil imports from India and heightened anti-Indian sentiment. Additionally, Nepal’s 2017 election of a communist government deepened India’s disapproval of its neighbor. The tensions brewing between the two countries grew in 2020 when India announced the completion of a new road in the disputed Kalapani border region, prompting Nepal to send its police forces to the area. Finally, in 2022, Nepal’s national election further intensified tensions when a communist Prime Minister was elected to head the coalition government.

India’s political dominance impacts Nepal’s external affairs as well. Experts argue that India’s hesitancy to form multilateral hydropower trade agreements hinders Nepal’s opportunities to sell energy to neighbors like Bangladesh. For Nepal to export power to Bangladesh, the transmission lines must pass through Indian territory, and India remains reluctant to permit neighboring countries to negotiate trade on their separate terms. The first trilateral agreement was passed in 2023 after a drawn-out process of negotiation. However, trade between Nepal and its South Asian neighbors still depends on India’s approval.

India and China Vie for A Stake in Nepal’s Hydropower Sector

India and China’s messy relationship—particularly the armed standoff over its shared Himalayan border—has made Nepal a geopolitical battleground. An ongoing military conflict over the two giants’ border territory has resulted in Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi implementing harsh conditions on India’s hydropower imports, refusing to purchase power from any Nepalese dams financed or constructed by the Chinese. Because of these conditions, experts fear Nepal’s relationship with China will suffer. One stakeholder said, “If we tilt too much towards India, China gets mad. If we tilt too much towards China, India gets mad. It’s hard to keep everyone happy.”

The transfer of hydropower dam ownership is a byproduct of this geopolitical struggle. The construction of the Budhi Gandaki Dam, for example, was originally contracted to the Chinese in 2017 as a BRI project. A shift in the Nepalese government and concern about the project’s implementation resulted in the construction process being turned over to Indian contractors shortly after. Now, ownership of the Budhi Gandaki Dam contract has been returned to the Nepalese government. Because of frustration with this political inconsistency, some interviewees expressed that China may be canceling construction projects in Nepal and letting India take the lead in the hydropower sector. India has more electricity and water demand as well as the technological capacity to import power easily from Nepal. However, China is still one of the largest investors in Nepalese infrastructure, with Chinese investments amounting to $2 billion from 2000–2021. Successful BRI projects in Nepal have made China a trustworthy development partner, and according to our experts, it will be difficult to know how this trend will impact country-to-country relations.

While many stakeholders and policymakers voiced concerns about India’s dominance in Nepal’s hydropower sector, others claimed that Nepal should make financially beneficial decisions without considering geopolitical implications. India has agreed to buy hydropower from Nepal for the long-term, thereby securing future revenue for the Nepalese government. Additionally, Nepal may be able to generate excess hydropower during the monsoon period (roughly between June and September) when India’s demand for electricity is the highest. Nepal has produced hydropower for years (since 1911) but has been unable to tap into its full potential because no market was available. According to some interviewees with a financial background, India’s investment and willingness to import is a crucial opportunity for Nepal.

Domestic Demand for Electricity

Nepal’s future economic growth relies on hydropower, but hinges equally on securing a foreign market and on building a robust domestic market for electricity. Stakeholders and thought leaders, whom we spoke to, in the public and private sectors believe Nepal’s government lacks a holistic approach to the country’s hydropower development—especially for domestic markets. This limited perspective is due to political instability that leads to frequent policy changes and deters infrastructure and industry development. Both are fundamental to increasing domestic electricity consumption and industrialization for an in-country market.

According to the Nepal Electricity Authority annual report, 37.5 percent of the domestic consumers consume less than 20 kWh of electricity per month. This low consumption is because electricity is primarily used to power domestic lighting. To increase the domestic electricity consumption from hydropower sources, public and private sector experts favor initiatives that promote electric stoves and the widespread use of electric vehicles. Though the Nepalese government has publicly set goals for increasing the units of electric stoves and vehicles, experts argue that such goals require proper and reliable infrastructure, namely, electricity grids, transmission lines, and charging stations, which are currently insufficient to encourage Nepalis to embrace such initiatives.

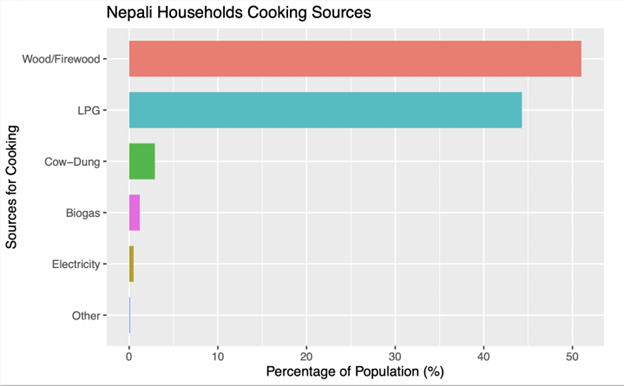

For many Nepali households, one of the main inhibitors of using electric stoves is that they will not work during power outages. From 2006–2016, Nepal faced up to fourteen-hour long power outages, scheduled and unscheduled. These outages have since been reduced significantly, but still occur with some frequency. Currently, many Nepali households use biomass or gas stoves for cooking purposes. The 2021 Nepal census reports that 51 percent of households use wood/firewood, 44.3 percent use liquefied petroleum gas (LPG), and 2.9 percent use cow dung as the primary source of fuel for cooking. Meanwhile, only 0.5 percent of households use electricity. Though the Nepal Electricity Authority provided 180 GW of free energy in 2023 by subsidizing usage of less than 20 kWh at 5 Amperes, irregular electricity supply due to lack of infrastructure has deterred many people from using electricity or transitioning to electric stoves, requiring Nepal to import fuel rather than consume electricity produced through own hydropower. Recently, Nepal signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) to expand the construction of a cross-border oil pipeline with India. At the same time, the Nepal Electricity Authority inaugurated over fifty electric vehicle charging stations. Experts argue that government policy is inconsistent and that a holistic approach to hydropower development requires the government to invest in the necessary infrastructure for electrification, not fuel.

Image 4: Nepali Household Cooking Sources

Source: Nepal Census, 2021

Although the electrification of public transport has begun in many countries, Nepal once led the initiative with Safa Tempos. Safa Tempos are battery-powered, zero-carbon emission three-wheelers that can seat up to twelve people. The Global Resources Institute, in partnership with the US Asia Environment Partnership, National Association of State Development Agencies, USAID, and the Nepal Electric Vehicle Industry, introduced the vehicle to Kathmandu Valley in the mid-1990s to limit pollution. Though initially successful, the costs of assembling Safa Tempos in tandem with government policy lowering tariffs on petrol-fueled microbuses dissuaded investment in Safa Tempos and encouraged investment in microbuses. The remaining Safa Tempos scattered throughout the Kathmandu Valley today symbolize the potential to electrify public transportation. If utilized, electric vehicles would build Nepal’s market for domestic electricity consumption of hydropower and industry development.

Hydropower as a Catalyst for Industrialization

The case of Safa Tempos exemplifies that industry development, and more generally industrialization, is another avenue to increase Nepal’s domestic electricity demand. Experts in the public and private sectors agree that industrialization leads to higher industrial electricity consumption, increasing domestic electricity demand. Furthermore, industrialization encourages economic growth by providing jobs and boosting Nepal’s domestic economy by producing finished goods. However, Nepal’s industrialization efforts also depend on government policy, which have been unclear and unstable.

Experts argued that to motivate entrepreneurs to start industries in Nepal, the country must have stable policies and clear bureaucratic procedures. Many also stated that industrialization policies must first accommodate Nepal’s competitive advantage and prioritize industries accordingly—especially neighboring India and China. While some argued for industries producing manufactured goods, others argued for more investment in the information and communications technology industry. Regardless of industry focus, interviewees expressed that industrialization and domestic consumption policies require investment in infrastructure and stable government policy.

A Geostrategic Chessboard and US Foreign Policy Implications in the Himalayas

Nepal sits at a geopolitical crossroads where China and India are strategically maneuvering in the critical arena of hydropower development. Nepal’s vast potential for hydropower production has placed it squarely on the radar of US foreign policy interests in the region. The United States, keenly aware of this, should monitor the geostrategic implications of energy resources.

With its expansive Belt and Road Initiative, China envisions Nepal as a pivotal link in its ambitious global connectivity and economic expansion vision. Through strategic investments and infrastructure projects, China aims to deepen its influence in Nepal and establish cross-border energy networks that could connect Nepal’s rivers to the energy-hungry markets of its western provinces. This pursuit aligns with the United States’ broader concerns about China’s growing influence in South Asia.

On the other hand, India, a long-standing US partner, also recognizes the strategic importance of Nepal’s hydropower potential. Leveraging its historical ties, India seeks to collaborate on joint hydropower ventures that address Nepal’s energy shortages and foster stronger regional integration. Washington supports regional cooperation efforts to promote regional stability and economic development in South Asia.

Yet, Nepal faces a complex array of challenges on its path to harnessing hydropower. Political instability, stemming from a decade-long civil war and ongoing political transitions, poses a considerable hurdle to foreign investment and regulatory consistency—a concern for US foreign policy objectives in the region. The labyrinthine bureaucratic landscape and the near-absence of reservoirs for off-peak water storage further hinder progress, raising questions about the viability of US engagement in Nepal’s energy sector.

Moreover, Nepal finds itself caught in the crossfire of the geopolitical rivalry between the United States (and India as a proxy) and China. As the superpowers assert their influence in Nepal through investments in infrastructure, including hydropower, Nepal must navigate these complex relationships while pursuing its own development goals. America faces the challenge of balancing support for its regional allies and maintaining South Asian stability.

Nepal’s journey toward realizing its hydropower potential has a heightened significance for US foreign policy. The United States should carefully assess the implications of China and India’s growing presence in the region and its impact on regional stability, energy security, and US interests. Balancing these considerations with support for Nepal’s economic development and energy needs will be essential as the United States navigates the challenges and opportunities on the Himalayan chessboard. The outcome of this delicate geopolitical dance will undoubtedly help shape US foreign policy priorities in South Asia for years to come.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Foreign Policy Research Institute, a non-partisan organization that seeks to publish well-argued, policy-oriented articles on American foreign policy and national security priorities.

This research came out of a larger research collaboration, Nepal Water Initiative, funded by the Global Research Institute, Institute for Integrative Conservation, Virginia Institute of Marine Science, and William & Mary.

Correction: A previous version of this article incorrectly stated that Chinese investment in Nepalese infrastructure between 2000 and 2017 exceeded $1.4 trillion. The figure is roughly $2 billion.

No comments:

Post a Comment