ANDREW JONES

2023 has been an unprecedentedly busy year for China’s space industry. Space station missions, satellite internet tests, a new launch record, moon partnerships, crewed lunar landing plans and a breakthrough year for commercial launch startup are just some of the highlights as Chinese space activities continue to grow in scope and intensity. Here I give a brief review some of the major developments and notable trends that emerged during the year.

China attracts partners for Moon base project

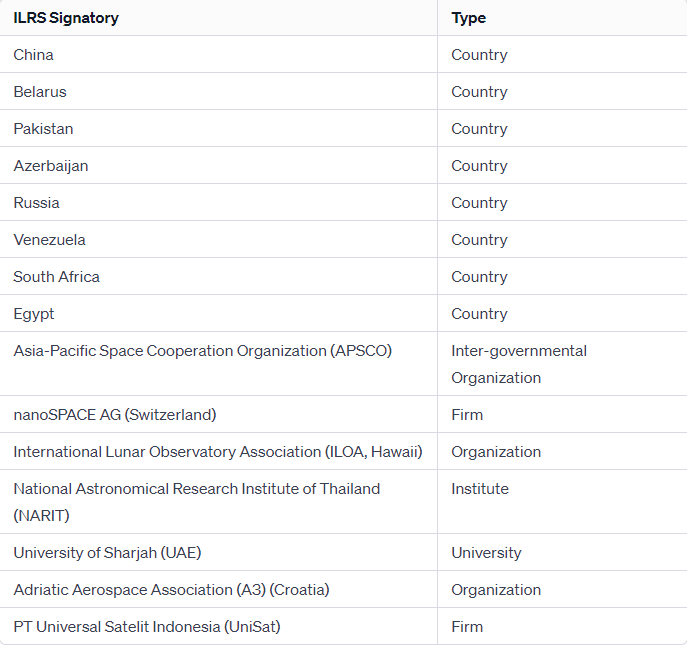

The China-led International Lunar Research Station is seen as a competitor to the U.S. Artemis project and this year it began formally collecting partners for the megaproject. Russia, despite for a long time not being mentioned in presentations and press in the wake of its invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, remains a core, if diminished, partner. China’s new Deep Space Exploration Laboratory (DSEL) stated in June that the country aimed to set up an organizing body, the ILRSCO, by October this year and forge agreements with founder partners. Cooperation deals were still being made in December, but China has already garnered support from some of its more likely allies. Absent are European nations it hoped to attract when officially announcing the project back in 2021. Below is a list of known ILRS participants as of late December 2023.

Chinese boots on the Moon by 2030

China this year committed to a preliminary plan to put two astronauts on the Moon for a short period to conduct scientific tasks and collect samples by 2030, according to Zhang Hailian of the China Manned Space Agency (CMSA). The mission entails launching a crewed spacecraft and a lander on separate Long March 10 rockets. These components will rendezvous and dock in lunar orbit before attempting a moon landing. The announcement is backed up by recent work and progress on the Long March 10, a new-generation crew spacecraft (which will thankfully get a proper name in the future), a lander, spacesuits and a rover.

The announcement is a big deal — it would, if accomplished, see China match a technological, engineering and economic feat achieved only by the United States. And as Artemis missions face a number of delays, some are wondering which nation will land astronauts on the Moon again first.

A New launch record

When a Long March 3B lifted off from Xichang early UTC on Boxing Day, it saw the country break its national record for launches in a calendar year. The falling boosters also almost smashed more than mere records. The mission was China’s 65th orbital launch of 2023, surpassing the 64 in 2022, which itself had obliterated the record of 55 set in 2021.

Commercial launch companies (Galactic Energy, Landspace, Space Pioneer, Expace, CAS Space and iSpace) also accounted for 17 of the 66 launches as of Dec. 28. CASC’s Long March rocket, plus one CASC-spinoff China Rocket Jielong-3, executed the rest. Expect yet more launches going forward, due to megaconstellation plans (Guowang AND G60) and new commercial launch pads.

A few caveats: CASC, although not suffering a failure since 2020, did not reach its own declared goals of 60+ launches. By comparison, SpaceX performed nearly 100 launches itself, and sent vastly more to orbit in terms of mass. Together, China and SpaceX contributed to the busiest global launch year so far.

Above: A Long March 5 lifts off from Wenchang carrying the classified Yaogan-41 GEO optical satellite. Credit: CASC

Liftoff for commercial liquid launchers

The dawn of Chinese commercial space launch firms occurred in late 2014 with a government policy change, opening the sector to private capital. Until December 2022, all commercial launches had been light-lift, solid rockets, some more successful than others. The plans for larger, more complex liquid propellant rockets, many with an eye on reusability, had taken much longer to develop.

In April one of the second group of emerging launch startups, Space Pioneer, became the first to reach orbit with a liquid rocket: the kerosene-liquid oxygen Tianlong-2. Landspace then marked a global first when the second flight of its Zhuque-2 methane-fuelled rocket achieved orbit. This breakthrough heralds greater launch capabilities available to China. It also hints at the direction in which these startups are moving…

Commercial launchers are growing

The first wave of commercial launch startups in China began developing light-lift launchers, stating that they were looking to secure contracts to launch small payloads such as university-led science missions and carefully state they would not step on the toes of CASC. The way to profit and sustainability was not clear. Medium-lift liquid, reusable launchers were also part of longer term development plans.

There have however been developments—the Guowang low Earth orbit (LEO) communications megaconstellation and possible space station missions—that are open to commercial participation and call for larger rockets. These firms are responding. While Tianlong-2 was a big moment, it is Tianlong-3—scheduled to launch in June 2024 and capable of carrying 17 tons to LEO and reusable in the future—that is a game-changer. Landspace, whose Zhuque-2 will be capable of carrying 6 tons to LEO, has now announced plans for a Zhuque-3 stainless steel methalox rocket. This is to be able to lift 21 tons to LEO when expendable or up to 18,300 kg when the first stage is recovered downrange. This ambitious, capital-intensive effort is targeting a 2025 first flight.

Galactic Energy meanwhile aims to launch the 5-tons-to-LEO Pallas-1 in late 2024. It wants to fly a triple-core, 14-tons-to-LEO version in 2026. iSpace scrapped its smaller methalox Hyperbola-2 plans and is focusing for 13.4-metric-ton to LEO Hyperbola-3 rocket in 2025.

All of this promises China more launch capability—particularly useful for getting the thousands of satellites into orbit needed to meet ITU deadlines—the utilization of reusability and lower launch prices. China is also expanding it spaceports to help meet the growing demand for launch.

Towards a reusable Long March 9

Work on a Long March 9 has been ongoing in the background for long years already. It was initially envisioned as an expendable 10-meter-diameter kerosene rocket with four boosters comparable to a Long March 5 stage—currently China’s largest rocket—and variously stated to be targeting 2028-2030 for a test launch. But the China Academy of Launch Vehicle Technology (CALT), the rocket’s designer, has shifted with changes in the launch sector.

CALT is now working on a fully reusable version of the Long March 9 rocket inspired by SpaceX's Starship, and says it has finalized the structural design and is focusing on methane-liquid oxygen propellant.

Specifications and Capabilities:

The initial version of the Long March 9 rocket will be 114 meters long, weigh 4,400 tons at liftoff, and generate 6,100 tons of thrust.

It will be a three-stage rocket, featuring full flow staged combustion methane engines on the first stage.

The rocket is capable of carrying 50 tons to lunar transfer orbit or 35 tons with the first stage recovered.

Future Variants and Goals:

A two-stage variant is planned, capable of carrying 150 tons to low Earth orbit (LEO), or 100 tons with the first stage landing.

The ultimate goal is a fully reusable variant, expected in the 2040s, capable of carrying 80 tons to LEO.

Given the 2033 test flight target, this could impact China's International Lunar Research Station (ILRS) project plans, the construction of which was slated to begin in the early 2030s using CZ-9. As well as the ILRS, the Long March 9 could be used for launching components for a space-based solar power station in geostationary orbit and deep space exploration efforts.

Satellite internet: Guowang and G60

Now there are two of them. China announced its Guowang plan for a 13,000-satellite megaconstellation in 2021. The pace of the project has appeared slow, but this year apparent internet technology test satellites have made it to orbit. Batch launches can be expected before too, long, possibly using a the Long March 5B and an upper stage, and/or the Long March 8. Not only that, but a second, Shanghai-based G60 project has emerged, apparently from the rubble of a joint Sino-German venture that ended in acrimony. A first satellite was produced in late December, with plans for a first-phase 108 satellites to launch in 2024.

Expanding Tiangong

China has established a space station and has carried regular crew and cargo missions to Tiangong, including Shenzhou-16 and 17 and Tianzhou-6 this year, including a more experimental spacewalk to attempt repairs. Now, it is looking to expand the orbital outpost: not just with the planned Xuntian co-orbiting space telescope, but by extending from three to six modules. First move will be to add multi-functional expansion module with six docking ports in around four years. China will likely have an interest in international participation in the expansion, to boost soft power efforts, space diplomacy and cover costs.

A view of Tiangong from the departing Shenzhou-16 spacecraft. Credit: CMSA

Commercial cargo with Chinese characteristics

China is also looking at other ways to utilize Tiangong. Learning from NASA, it opened a call for proposals for low-cost cargo systems to Tiangong. While commercial companies were able to apply, only state-owned firms were selected for the cargo spacecraft. However, it seems that commercial launch firms have opportunities to launch said spacecraft.

Hop tests heat up

Reusability has long been a goal for Chinese commercial firms. Both Linkspace and Deep Blue Aerospace have conducted launch and landing tests with altitudes reaching hundreds of meters in recent years (and jet engine-powered tests by CASC, CAS Space and Galactic Energy), but iSpace recently carried out the first using an engine that will power an orbital launch vehicle. Landspace is also getting ready for hops as part of its Zhuque-3 program. More vertical takeoff, vertical landings will be carried out by firms as development continues.

iSpace’s Hyperbola-2Y test article during a hop test at Jiuquan spaceport. Credit: iSpace

RIP Zhurong

Zhurong, the solar-powered rover that touched down on Mars in May 2021 as part of China’s first independent interplanetary mission, went into hibernation for winter in the Red Planet’s northern hemisphere in May 2022. It was supposed to reactivate itself in mid-December that year, following the onset of spring and sufficient energy and light levels reaching the rover. That did not happen. With the passing of the summer solstice in July this year, the last hopes that Zhurong—which likely suffered greater than expected coverage of Martian dust on its solar panels—appear to have faded. The rover however achieved its primary objectives and embarked on an extended drive and data-gathering mission before its demise.

No comments:

Post a Comment