Jeremy Mark and Niels Graham

Global attention to Taiwan tends to focus on China’s military threats and punitive economic actions.1 Combined with US officials’ periodic warnings about an imminent Chinese invasion, these developments suggest that the balance of power between China and Taiwan has tilted decidedly to Beijing’s advantage, underlining Taipei’s increasing vulnerability.2

But a wider view highlights an uneasy economic equilibrium that has constrained Beijing’s worst impulses. Cross-strait relations are anchored in global supply chains built around Taiwan-made semiconductors and Taiwanese electronics manufacturers’ investments on the mainland.3 If anything, China is becoming more dependent on its business ties to Taiwan as it experiences an unprecedented economic downturn and as foreign multinationals begin to move their factories to other countries. China’s economic vulnerabilities are deep, and its reliance on Taiwan is profound.

Dependence works both ways. Taiwan’s exports to China have enabled its economy to enjoy strong growth, especially after receiving a lift from the COVID-19 electronics boom. This has made China more important to Taiwan’s economic well-being—no matter how ambivalent many Taiwanese feel about the trend. Clearly, a war in the Taiwan Strait or a Chinese blockade of Taiwan would have catastrophic implications for both countries, not to mention the impact on the global economy, as Atlantic Council and Rhodium Group colleagues have written.4 Neither Beijing nor Taipei is comfortable with this mutual dependence, and each government has been driven to seek alternatives. Beijing has expended vast resources on a largely unsuccessful effort to become technologically self-reliant. Taipei has sought new export markets and bases for manufacturing investments, especially in Southeast Asia and India. While Taiwanese companies have expanded to new markets, the economic ties across the Taiwan Strait will take decades to unwind—if such an outcome ultimately is possible—even with the push currently under way from Washington to restrict semiconductor sales to China.

Dependence on China also has laid bare homegrown Taiwanese economic vulnerabilities that require new policy thinking: the loss of dynamism in industries that previously drove Taiwan’s economic success; a rapidly aging population and labor shortages; and reduced opportunities for young people. Yet discussion of crucial economic issues has been muted—despite their importance for Taiwan’s future as the January 2024 presidential elections approach.

Many of these challenges reverberate far beyond Taiwan and China, not least because of Taiwan’s role in the semiconductor industry. But Taiwan’s place in the world is determined by much more than its technological prowess. It is a prosperous, democratic society that needs to be recognized and accepted for its many achievements. Its efforts to broaden its economic horizons beyond the constraints of the cross-strait relationship should be encouraged and advanced by the United States, the Asia-Pacific community, and the world at large. This challenge will be just as important as the imperative to strengthen military capabilities and alliances in the Asia-Pacific in the coming years.

This paper examines these issues under the assumption that military conflict in the Taiwan Strait is less imminent than some observers foresee. This is not to rule out such an eventuality; it would be foolish to do so in a world where the unthinkable has become all too commonplace. Indeed, Taiwan needs to continue strengthening its defenses in the face of Chinese threats—with support from the United States. But as Taiwanese businesses look to the future, the current status quo of trade and investment across the Taiwan Strait remains the baseline for their planning. Thus, it is essential to consider how economic relations between Taiwan and China might evolve in the coming years in the absence of military conflict—and how Taiwan might strengthen its position in Asia and the world under those circumstances.

Coercion and codependence

On April 12, 2023, China’s Ministry of Commerce announced an “investigation” into the “Taiwan area’s” barriers to 2,045 categories of Chinese exports. The inquiry was scheduled to be concluded in six months, but Beijing made clear it could be “extended to January 12, 2024 [sic] under special circumstances.”5 That would be the eve of Taiwan’s 2024 presidential elections—a clear message that Beijing is prepared to dangle the threat of economic coercion until Taiwanese voters go to the polls. By mid-August, the number of products under investigation had risen to 2,509 and the Ministry of Commerce declared that Taiwan’s restrictions violated World Trade Organization (WTO) principles.6 Unsurprisingly, the ministry announced on October 9 that the investigation would be extended to January 12, 2024, a move that Taiwan denounced as election interference and a violation of WTO norms.7

The inquest is just the latest step in Beijing’s campaign of economic coercion against Taiwan. Over the past eight years, China has sharply curtailed tourism travel to Taiwan and banned imports of food products ranging from pineapples to processed foods. Many of the punitive actions have been aimed at Taiwanese counties and companies that support the ruling Democratic Progressive Party. The most recent ban came in August, when China’s customs authority banned Taiwanese mangoes after allegedly detecting pests in a shipment.8

Beijing’s efforts to inflict economic pain on Taiwan over its alleged political transgressions are part of a broader policy aimed at coercing countries it perceives as acting against Chinese interests. Australian wine and barley exporters, Norwegian salmon farmers, and Korean department-store owners are all among those who have run afoul of China and faced sanctions. The Mercator Institute for China Studies reports 123 cases of Beijing’s coercive actions and threats between 2010 and 2022, many in response to governments’ policies toward Taiwan.9

The impact of China’s economic coercion toward Taiwan has largely been offset by government subsidies and export promotions in other countries. More importantly, in the larger economic picture, Beijing’s actions amount to little more than pinpricks for an export powerhouse like Taiwan. For example, the lost sales from products banned after the visit of US Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi in 2022 amounted to just a tiny percentage of Taiwan’s agricultural exports.10 More importantly, the affected exports pale in comparison with Taiwan’s shipments to China of semiconductors and other electronics, which play a key role in powering the Chinese export engine. Taiwan’s semiconductor industry and the Taiwanese electronics giants that assemble Apple iPhones, Sony PlayStations, and many other multinationals’ products in China, are simply too important for Beijing to punish—short of a decision to cut off its nose to spite its face.11

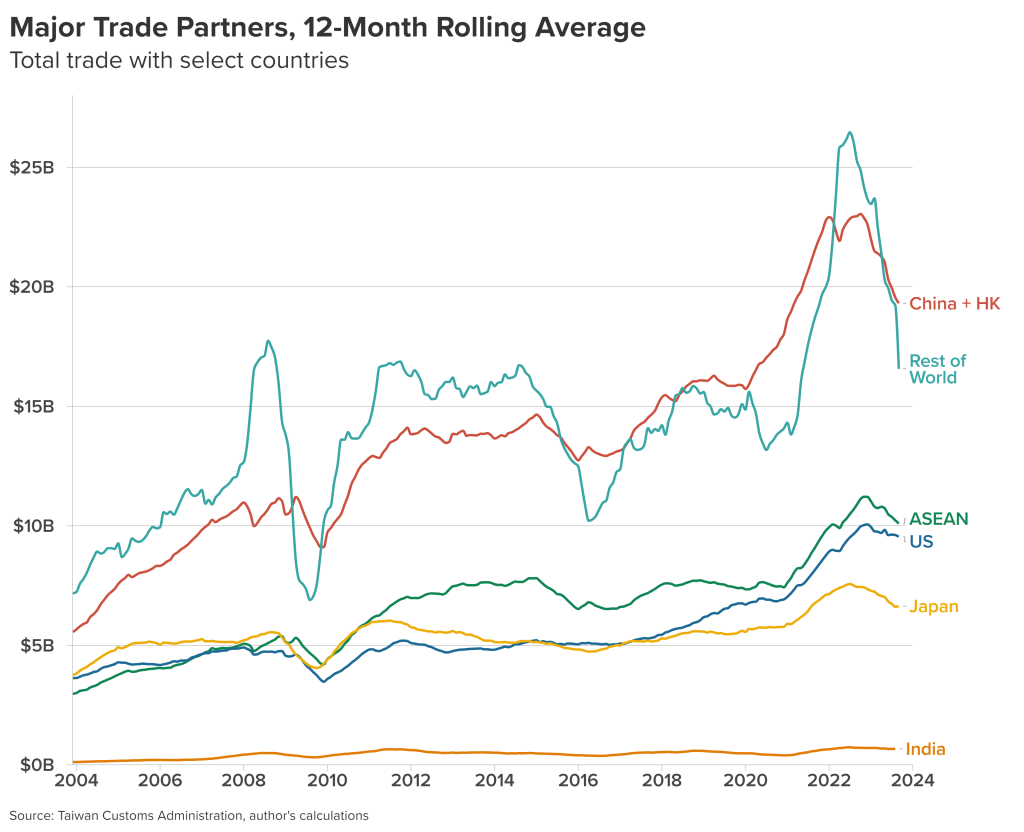

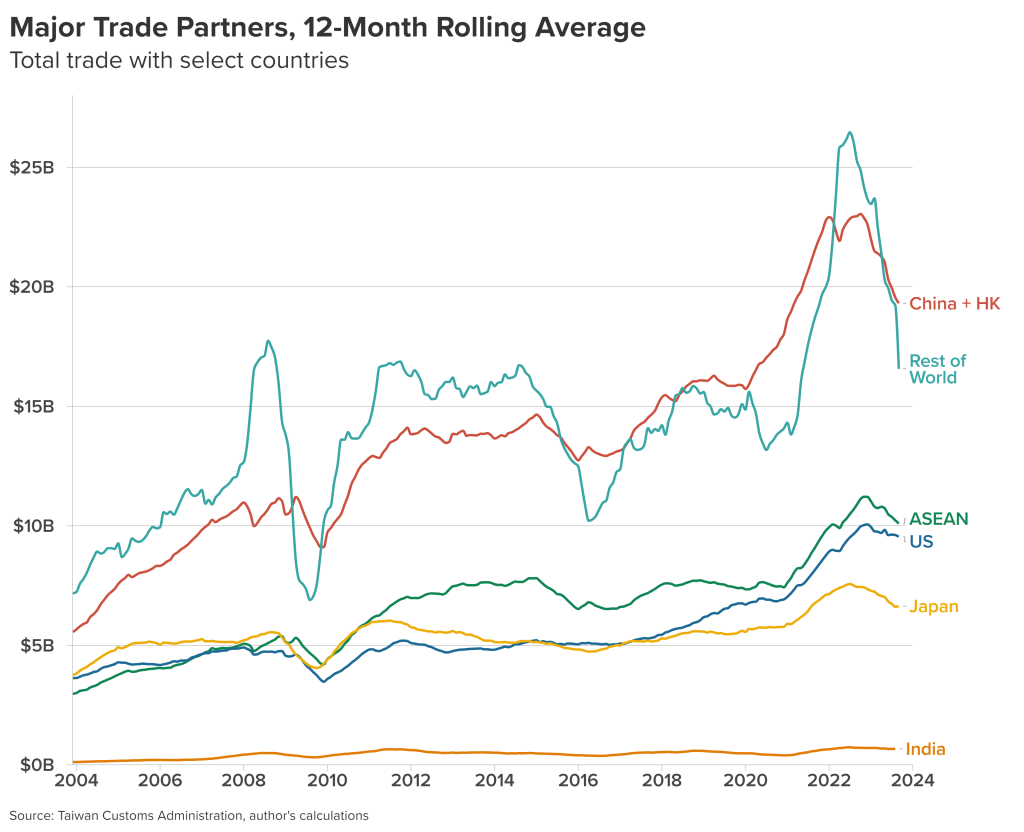

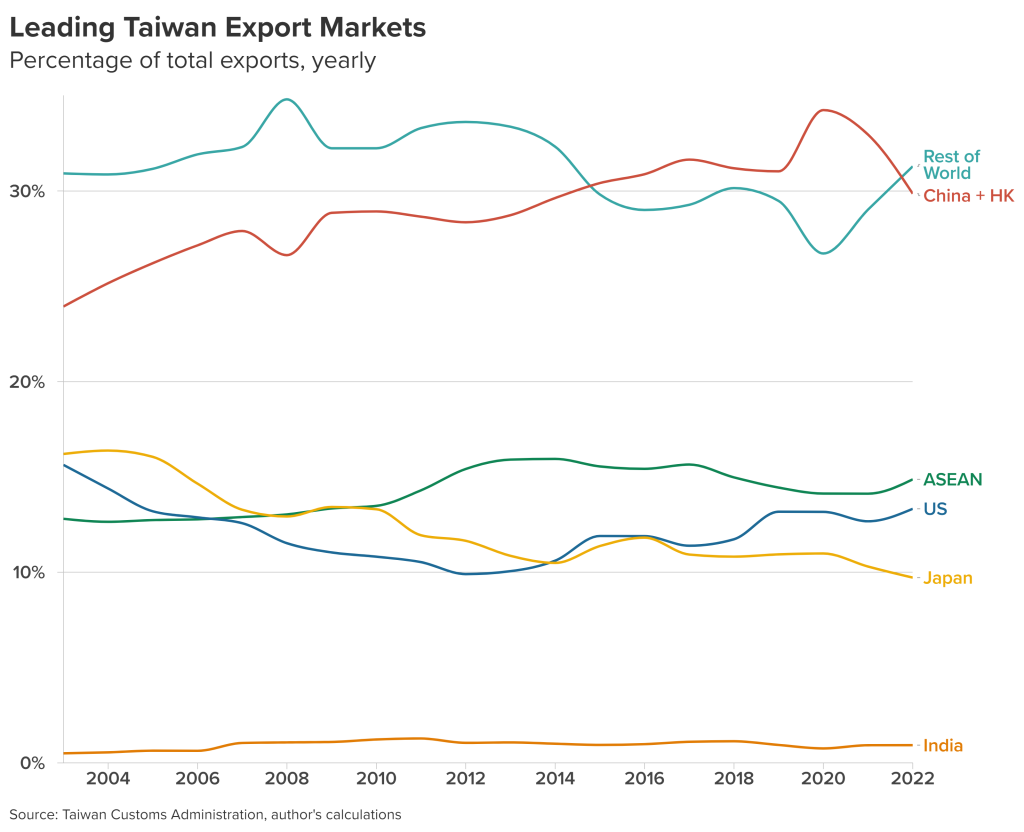

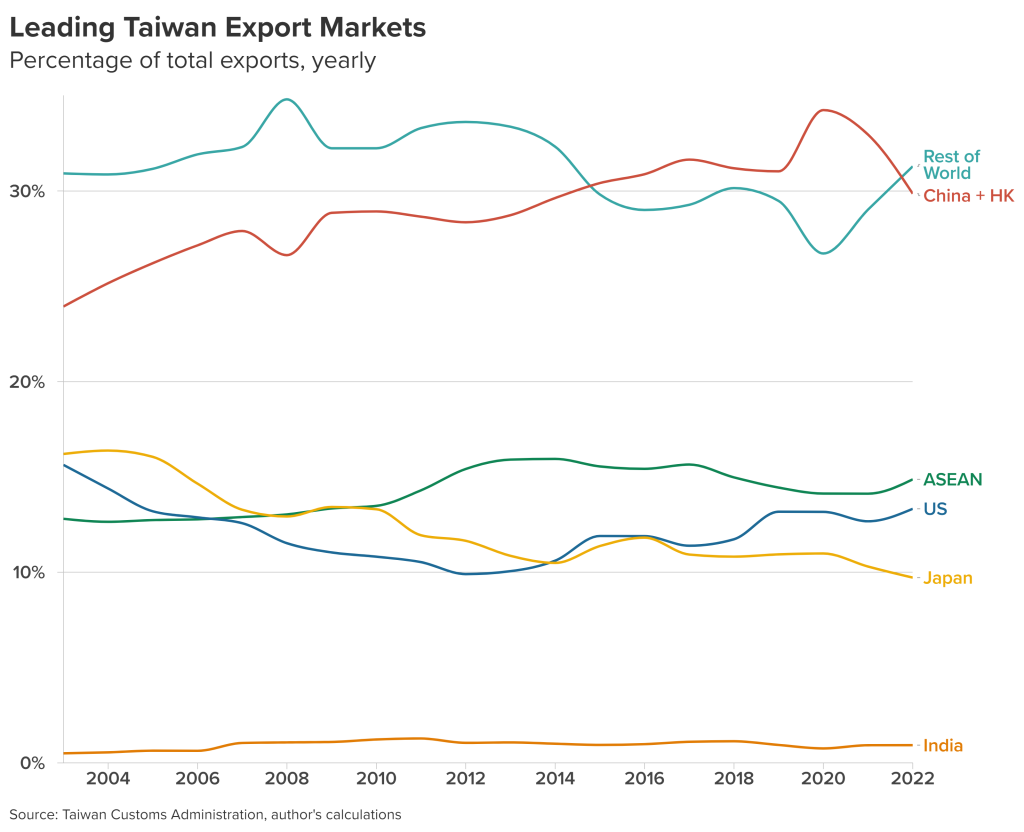

Trade and investment in electronics are the foundation of the uneasy economic embrace between Taiwan and China. A relationship that took root in the 1990s with the wholesale migration of Taiwanese makers of low-cost goods like shoes and toys has become the heart of electronics supply chains that power the global economy. An Economic Framework Cooperation Agreement (EFCA) signed by the two governments in 2010 (in which China accepted Taiwanese barriers to many of the Chinese exports that Beijing is now investigating) encouraged the rapid growth of trade.12 That cemented China as Taiwan’s premier trade partner in terms of total trade (Figure 1) and the percentage of exports sent to the mainland and Hong Kong (Figure 2).

Figure 1: Taiwan’s major trade partners

Figure 2: Leading export markets for Taiwan

COVID-19 gave an enormous boost to both countries’ exports as demand for electronics and other pandemic-related products skyrocketed from 2020 until late 2022. Taiwan experienced its strongest economic expansion in years, with gross domestic product (GDP) growth peaking in 2021 at 6.5 percent, and semiconductor exports in 2022 reaching nearly 25 percent of GDP.13

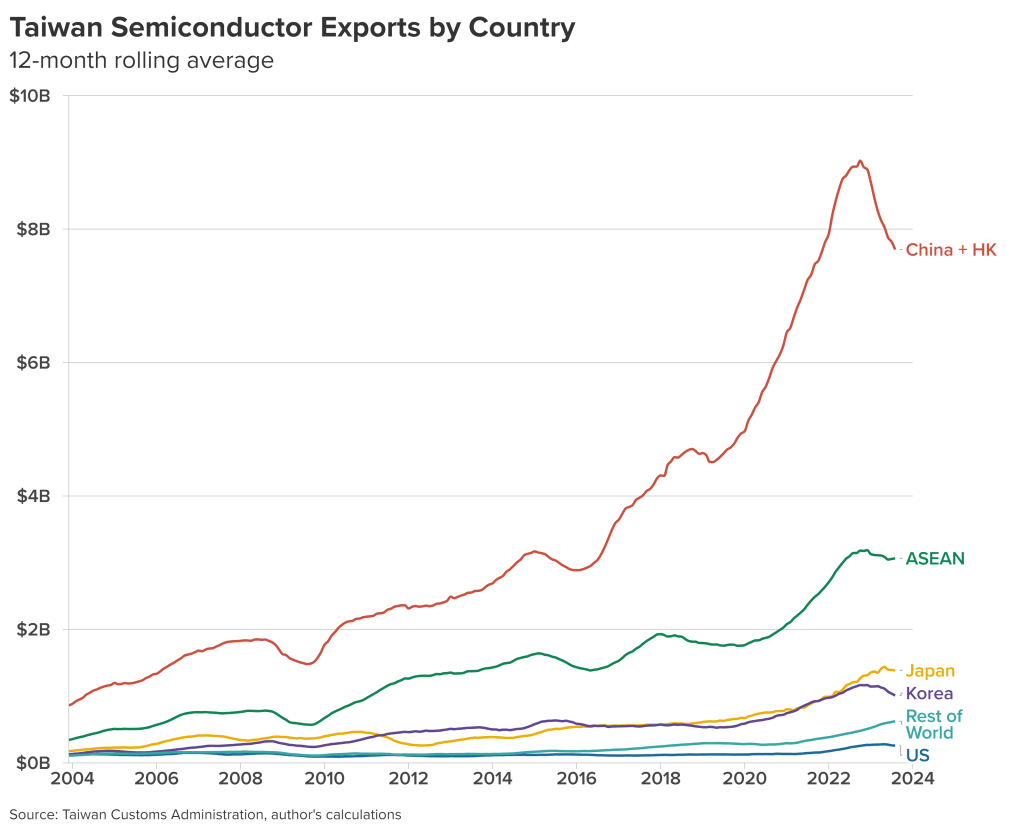

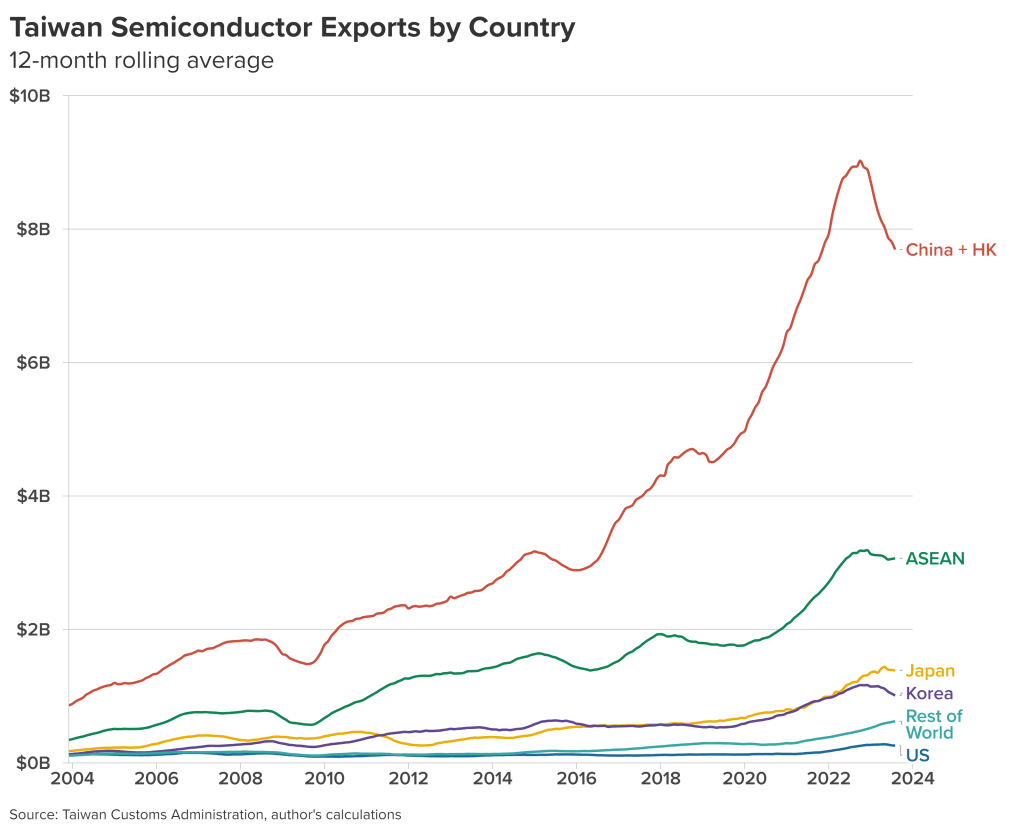

While a sharp slowdown in demand for semiconductors and other electronics briefly sent Taiwan into recession in early 2023, global demand is expected to rebound in 2024.14 Taiwan’s chip makers are already benefiting from the surge of investment in artificial intelligence (AI), and there are hopes that Taiwan’s semiconductor exports to China will begin to recover in the coming months (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Where Taiwan’s semiconductors go

Taiwan’s dependence on the Chinese economy has been framed by Beijing over the years as “integration.” The process gathered steam when President Ma Ying-jeou was in office, especially after the ECFA was signed. But that process of integration ground to a halt in the face of popular Taiwanese protests against implementation of a bilateral services-trade agreement in 2014, an accord that would have opened the Taiwan market much wider to China.15 Beijing’s recent high-profile announcements of investment and other incentives to Taiwanese businesses have been greeted with considerable skepticism in Taiwan, with little impact on economic ties.16

Beijing probably did not expect that its own modernization effort would come to rely so much on Taiwan: Taiwanese ventures in China are among the largest exporters from several Chinese provinces.17 Nor could China have imagined how much it would need Taiwan’s unprecedented achievements in semiconductors.

Semiconductors as an economic bastion

Taiwan has long understood the delicate balance in the economic ties that bind it to China. While Taipei saw the economic gains and political benefits of doing business across the strait, it also saw the downside of rising Chinese competitiveness, especially in the realm of technology.18

Nowhere was this tension more evident than in semiconductors, where Taiwan has emerged as a world leader in chip-manufacturing technology. Its industry is led by giant Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Corp. (TSMC), which produces more than 90 percent of the world’s most advanced logic chips.19 But China has also become an integral part of the complex global supply chains required to churn out chips. It plays a growing role in the production of earlier-generation integrated circuits—so-called “legacy chips”—and is the world leader in the more labor-intensive processes of chip assembly, packaging, and testing.20 Meanwhile, semiconductors go back and forth across the strait at various stages of production, with Taiwanese makers always holding the technological advantage.21

In time, this relationship built on chips came to be known as Taiwan’s “Silicon Shield,” with the semiconductor trade providing Taipei leverage in the cross-strait relationship.22 For example, amid Beijing’s angry response in the wake of the Pelosi visit, Taiwanese officials made clear that they saw “very little chance” of sanctions on the core electronics trade.23 But semiconductors are not an impermeable block on China’s ambitions to gain control over Taiwan. As a Council of Foreign Relations task force on “U.S.-Taiwan Relations in the New Era” said in a June 2023 report: “Taiwan’s critical role in supply chains—above all, semiconductor production—acts as a brake on hostilities but does not diminish China’s desire to gain control over Taiwan.”24

Nonetheless, the notion of semiconductor leverage has now become global, as the United States, Taiwan, Japan, the Netherlands, and South Korea, have restricted China’s access to the most advanced chips and semiconductor-making equipment. Washington also has clamped down on the flow of capital to China’s semiconductor industry through financial markets.25 China still relies on imported chips—to the tune of $415 billion worth in 2022—but it has lost access to the most sophisticated semiconductors for next-generation weapons, internal surveillance, and AI.26 Taiwan’s semiconductor manufacturers still churn out less-advanced chips for China, and that flow is likely to continue.

But Taiwan’s advantage over China is likely to slowly erode. Beijing has opened dozens of semiconductor fabrication plants in recent years, and many others are under construction—sometimes with Taiwanese companies involved in the building.27 While the ban on sales of high-end chip-making equipment will slow China’s efforts to produce the most advanced chips, Chinese companies will still make advances, as the recent unveiling of an advanced chip in a new Huawei Technologies Co. smartphone made clear.28 In addition, as Chinese production of legacy chips surges at its new factories, Taiwan’s smaller chip makers may begin to lose market share on the mainland. That doesn’t necessarily mean that they will suffer; global demand for all semiconductors is projected to nearly double by 2030 to about $1 trillion a year.29 But Taiwan’s essential place in the China market may weaken over time.30

Some of those customers will still be in China. Some 10 percent of TSMC’s sales continued to go to China in 2022 in the form of devices that are still allowed under US restrictions. Whether or not China’s vast expenditures to make its own advanced chips can progress enough to reduce its dependence on Taiwan, two of the biggest economic risks facing Taiwan for years to come will be the reality that its most important supply chains run through China and that cross-strait trade remains a core driver of Taiwanese economic growth.31

Taiwan’s expanding trade horizons

China’s rise as an economic power is deeply rooted in Taiwan’s own success over the past two generations. While many Chinese industries have outgrown their early Taiwanese investment partners, Taiwan’s technological advances and its deep connections to global supply chains have remained indispensable to China. This latticework of investments, trade ties, and technology transfers spurred the rapid expansion of Taiwanese exports (Figure 1), but it also set off alarm bells in Taipei.

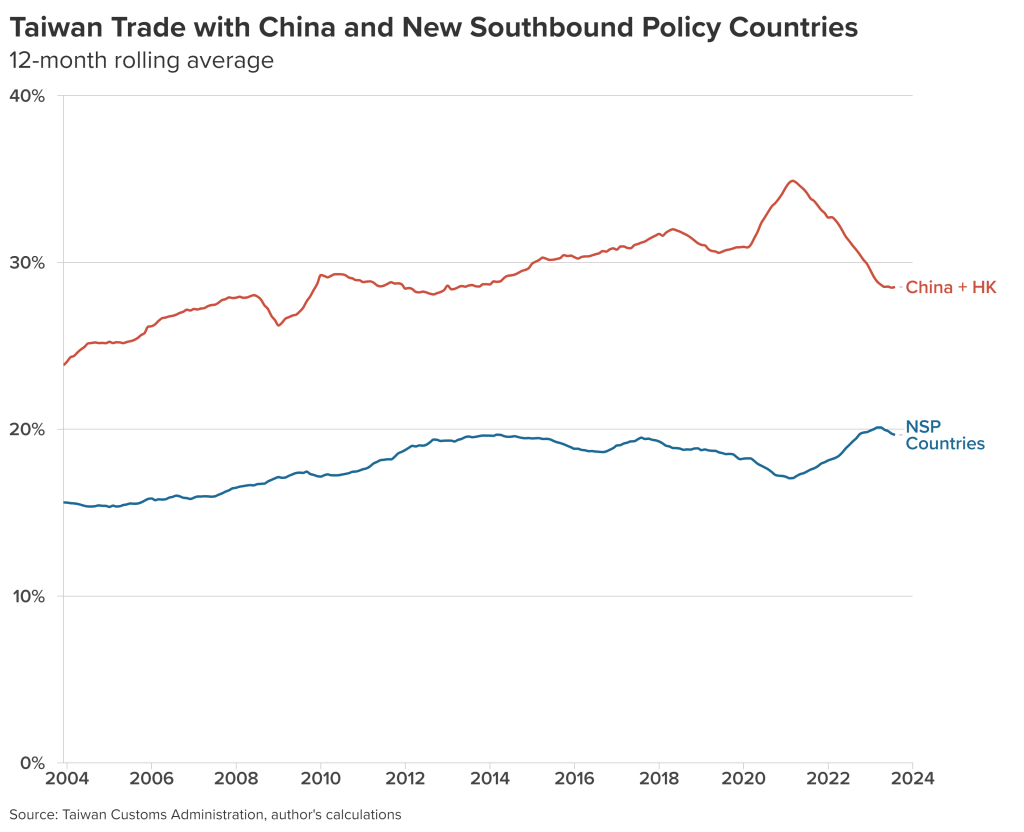

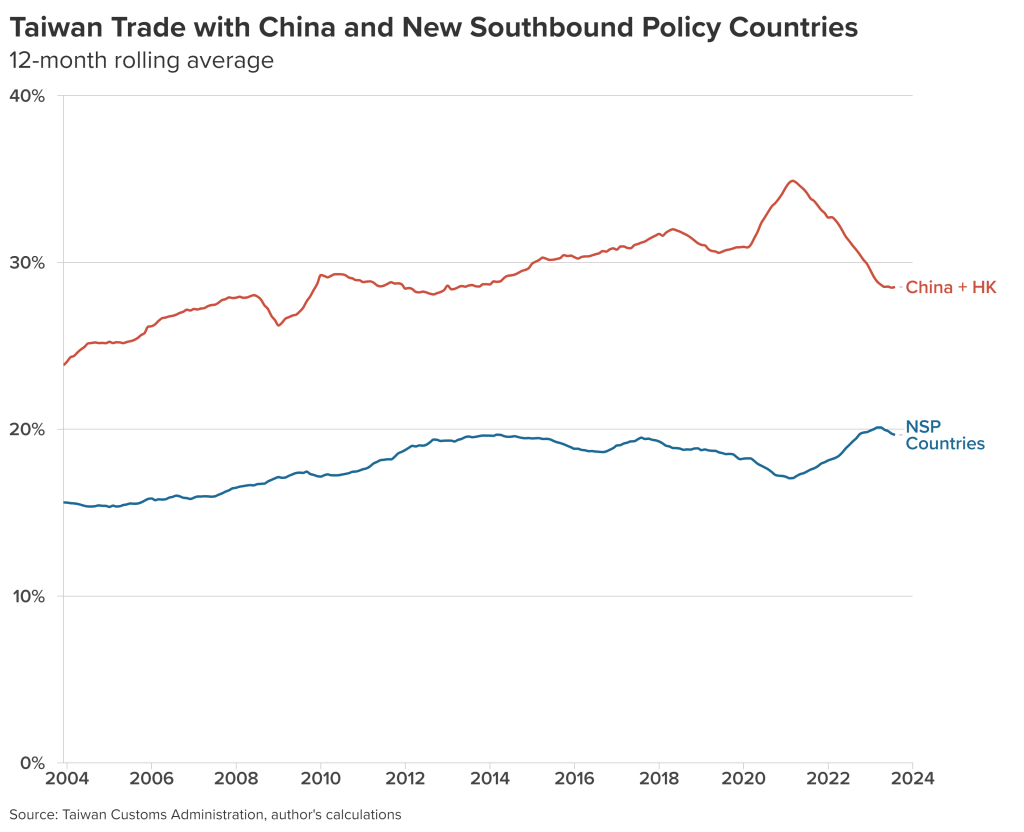

In 2016, President Tsai Ing-wen’s government launched a New Southbound Policy (NSP) with the goal of deepening Taiwan’s regional integration by expanding economic, technology, agricultural, educational, and cultural ties with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), South Asia, Australia, and New Zealand.32

The NSP met with modest success on the trade front.

Figure 4. Taiwan’s trade with China and “New Southbound Policy” countries

The results in terms of foreign direct investment (FDI) have been more notable. Taiwanese investment in the ASEAN countries, especially Vietnam, rose 73 percent in 2016 to $4.2 billion.33 But overall investment in NSP countries subsequently slowed during the early stages of the pandemic. It took a different set of shocks to set in motion a shift in priorities that is finally starting to turn Taiwan away from China. Rising labor costs on the mainland, the uncertainty of government policies—epitomized by Xi Jinping’s disastrous zero-COVID policies—and the deterioration of US-China relations have sparked a migration of supply chains out of China. While the process will be slow, multinationals are looking to new production bases, and they are urging their Taiwanese partners and suppliers to follow suit.

FDI to the NSP countries surpassed reported investment in the mainland for the first time in 2021.34 Between January and June 2023, Taiwanese investment in those countries totaled $2.13 billion, while its FDI in China was only $1.9 billion.35

This trend is visible in Apple’s supply chain, where many Taiwanese partners are already on the move.36 With Foxconn and other Taiwanese companies setting up shop in India, that country’s share of iPhone production this year is forecast to reach 19 percent of Apple’s global output, up from 10 percent in 2017. China will remain Foxconn’s core production base—it currently employs hundreds of thousands of Chinese workers versus tens of thousands of Indians—but iPhone assembly in China is declining.37

One spur to investment in the NSP countries is coming from an unexpected source. In 2018, the Tsai government offered financial inducements to businesses to move factories back to Taiwan from the mainland, a program that has produced an estimated $68 billion of “re-shored” investments (although some of that is said to be going to real estate investment).38 However, the nervousness ignited by deteriorating US-China relations, and especially the warnings about a Chinese invasion, have led some multinationals to reappraise Taiwan as an alternative to their Chinese manufacturing operations. Some Taiwanese suppliers have been asked to diversify away from both the mainland and their home country—in what has become known as a “Greater China+1” strategy of supply-chain security.39 That development has set off alarm bells in Taipei and may have led the Tsai government to ask the Biden administration to tone down the rhetoric about China’s threat to Taiwan.40

In time, the departure of some Taiwanese companies from China may begin to reduce Taiwan’s role in the Chinese economy. But relocating some factories is not an exodus. The intricacy of global supply chains means that Taiwanese manufacturers—like other foreign companies—will continue to rely on Chinese suppliers.41 In addition, the continued draw of China’s domestic market, bolstered by the many advantages of thirty years of investment in a country that offers language compatibility and an unparalleled network of suppliers, will likely cause many Taiwanese companies to remain, and even to grow their mainland operations.

Moreover, Taiwanese companies have little recourse to government financing to assist a move away from China. Taipei has failed to establish an export-financing mechanism large enough to meaningfully support companies seeking new markets beyond the mainland—an approach that Japan and South Korea have employed effectively. As of June 2020, the Export-Import Bank of the Republic of China had paid-in capital of only 31.7 billion New Taiwan dollars (NT$), equivalent to about $1 billion.42 Moreover, the Taiwan government has done little to materially support Taiwanese investments in NSP countries.

The reality is that the push for Taiwanese companies to move away from China likely will not be enough to reduce Taiwan’s reliance on China. It will also depend on Taiwan’s ability to address other economic weaknesses.

Vulnerabilities on the home front

Taiwan rose to become the world’s twenty-first largest economy on the back of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), a well-educated workforce and economic policies that facilitated growth and technological advancement. Its power as an exporter evolved over half a century across many sectors— from textiles to plastics to electronics. In recent years, growth has been anchored increasingly in semiconductors as other industries have lagged, and successive governments have tended to lean on Taiwan’s central bank to ensure economic stability while giving short shrift to long-term policy planning.

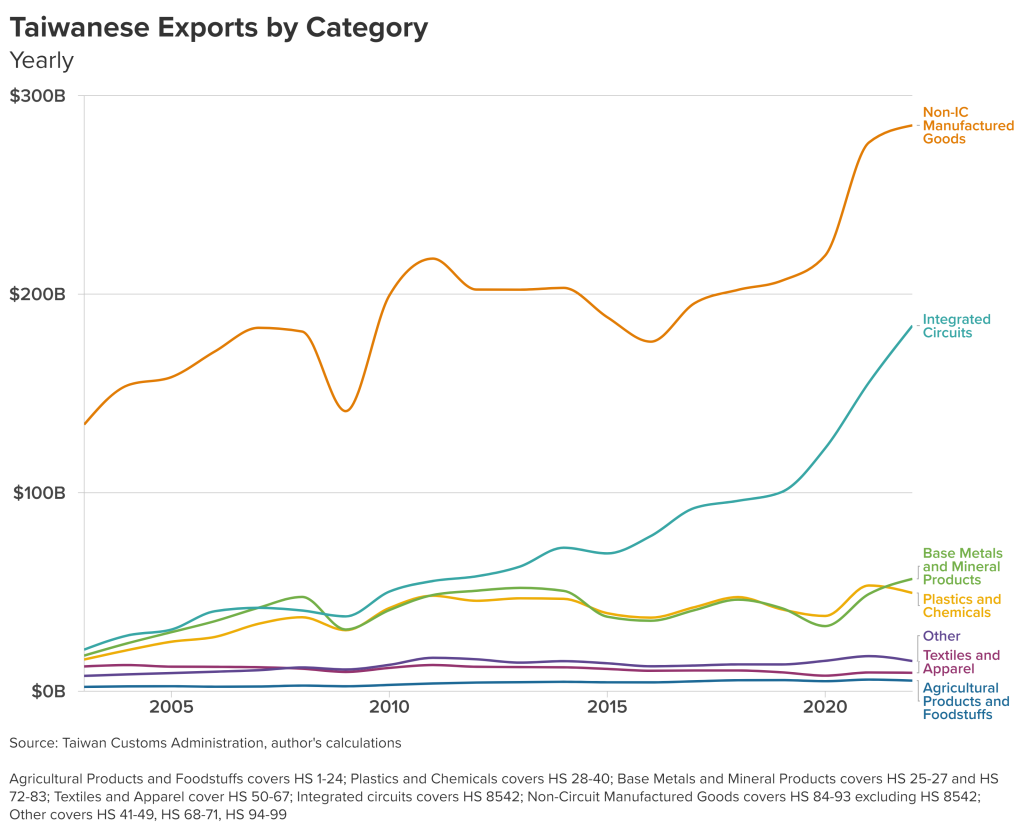

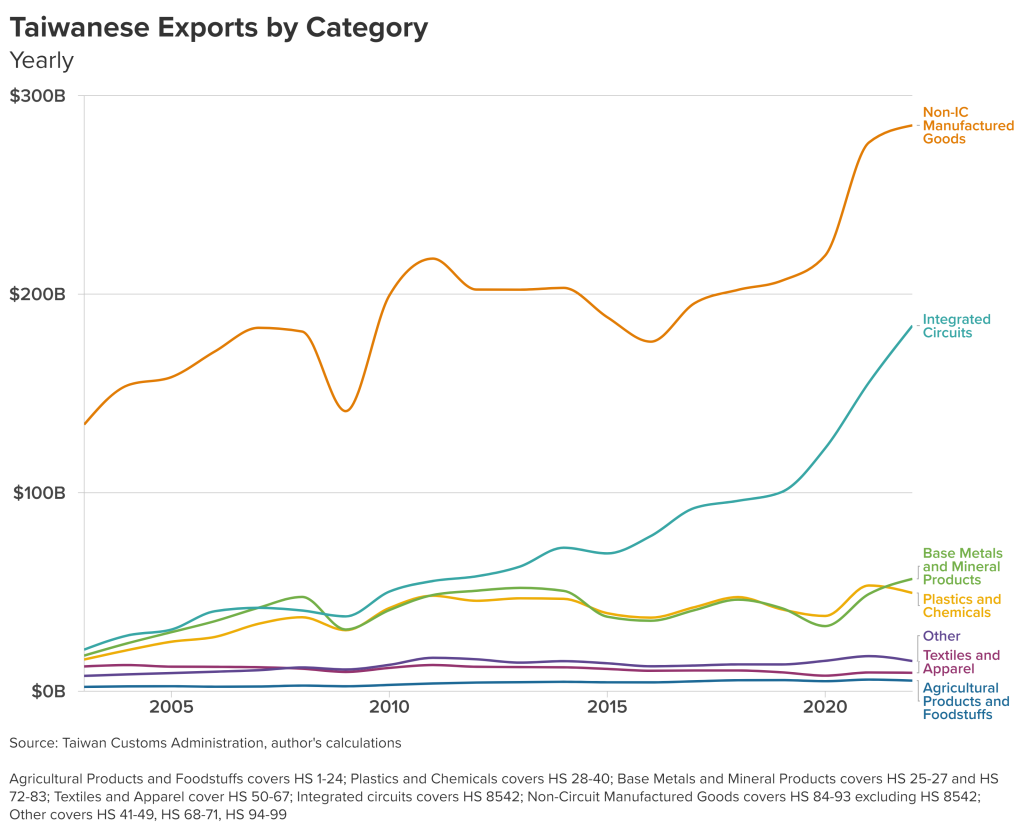

Export numbers paint a picture of industries experiencing slower growth.

Figure 5. Taiwanese exports by category

Important manufacturing sectors like plastics, chemicals, and iron and steel have struggled to sustain significant growth—with harder times likely to come. The key reason is massive capital investment by Chinese competitors. For example, Taiwan’s petrochemical manufacturers (and their counterparts in South Korea and Japan) are now looking at a looming oversupply of low-cost Chinese exports as more than twenty new factories have come online this year alone in China.43

Those changes in manufacturing show up most drastically in Taiwan’s once-stalwart SME sector. Smaller companies’ share of exports fell to 13.7 percent in 2018 from around 60 percent during the 1980s.44 By contrast, Taiwan’s soaring semiconductor exports represent about one-quarter of GDP.45 They are produced by the corporate opposite of SMEs: TSMC now boasts one of the world’s fifteen-largest stock-market capitalizations.46

Taiwan’s government is cognizant of the declining vitality of various industries and has promoted diversification in fields such as AI powered applications and biotechnology under a “5+2 Innovative Industries Plan” and the “Six Core Strategic Industries” blueprint. But such plans tend to be underfunded and over-touted.47

Without effective diversification into new fields, Taiwan’s economy will increasingly depend on the cyclical fortunes of the semiconductor industry. One important path forward involves cooperating with multinational partners in R&D. Over the past few years, Google, Microsoft, and other corporations have established research centers in Taiwan. In an era of cross-border technological development, it is an area that needs to be encouraged with more government support.48

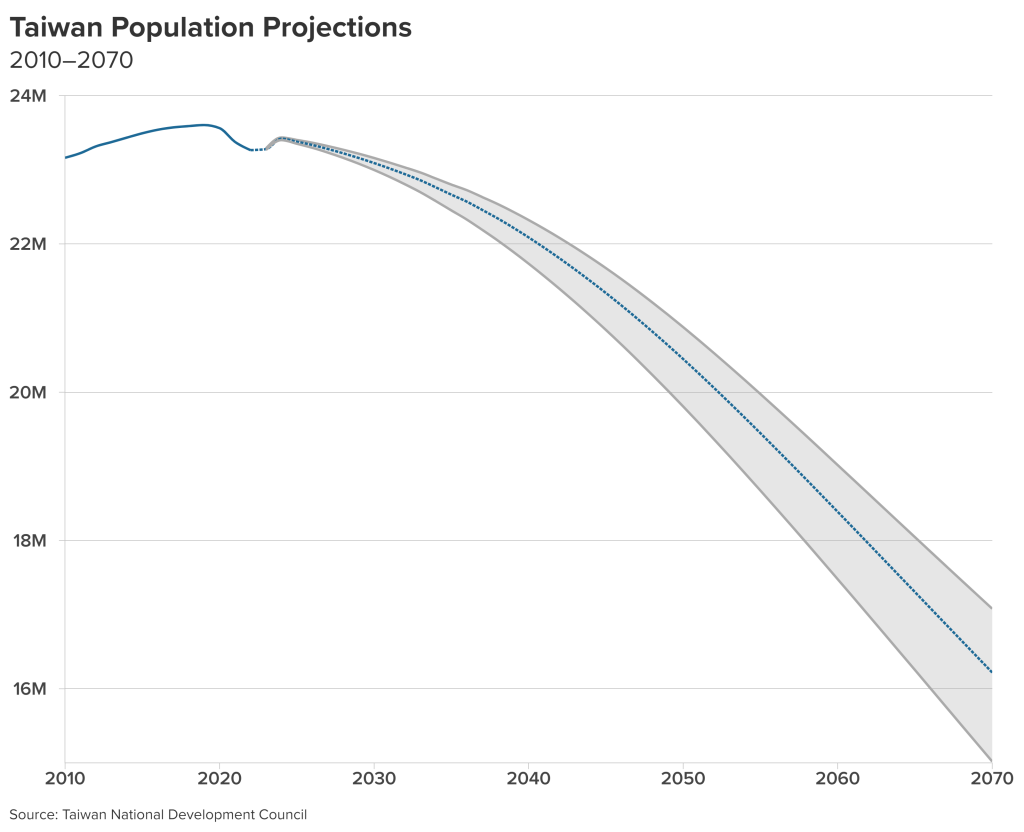

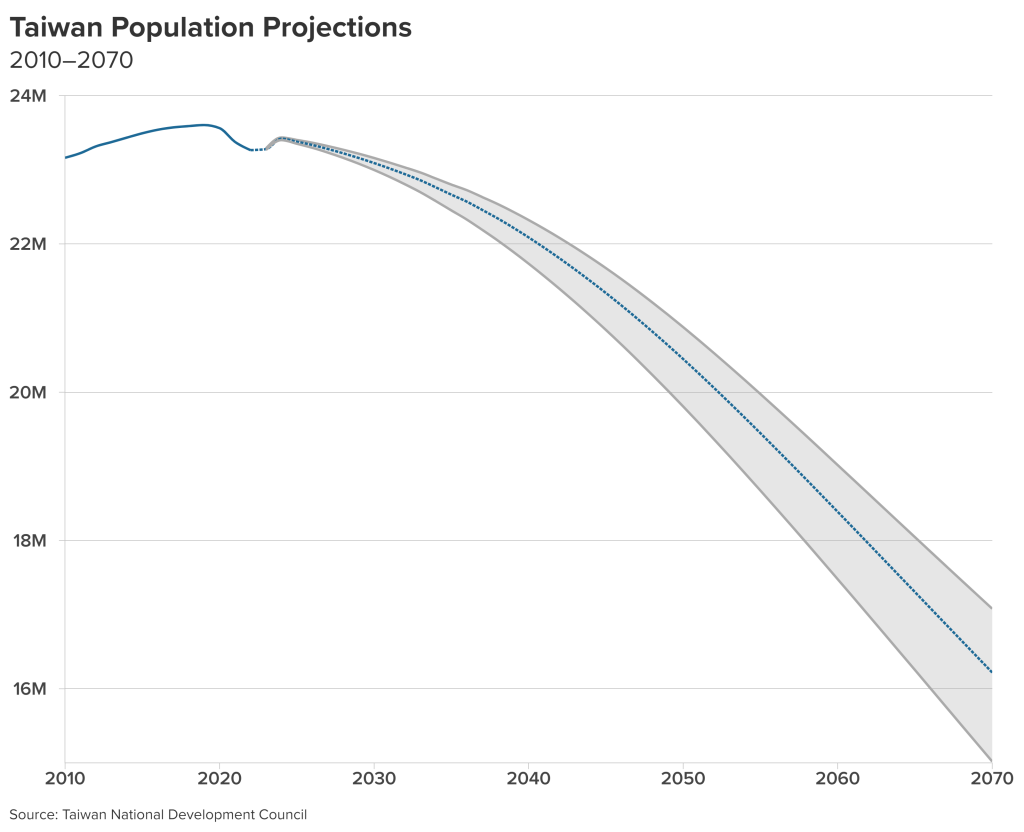

That said, Taiwan faces a shortage of qualified scientists, engineers, and technicians. Its universities are not graduating the numbers of specialists needed for the new fields—let alone those needed by its semiconductor industry.49 That underlines a more worrying vulnerability: the country’s rapidly aging population. Like other East Asian countries—China, Japan, and South Korea—Taiwan’s birthrate is falling sharply, to less than one child per woman of childbearing age.50 The working-age population peaked in 2014, and the total population began declining in 2020.51 Taiwan’s National Development Council forecast in 2018 that by 2070, there will be 1.2 people in their working prime to support each person over 65 years of age. That compares with a five-to-one ratio in 2018.52

Figure 6. Taiwanese population projections

In the face of these looming demographic changes, it is notable how pessimistic Taiwan’s young people have become about the future. One key reason is the paucity of well-paid jobs outside the semiconductor industry. Despite an increasingly severe labor shortage across the economy, many young Taiwanese face limited career opportunities. Real wages, adjusted for inflation, were stagnant in the years leading up to the pandemic.53 That has led to rising intergenerational income inequality, exacerbated by high real-estate prices that put homeownership out of reach.

It is small wonder, then, that public-opinion polling has found deepening pessimism about the economic outlook.54 To be fair, this has been a common theme since Taiwan began holding democratic elections during the 1990s.55 But these increasingly important economic issues—what one academic calls Taiwan’s “high-income trap”—will present the next government with severe challenges.56 They are also issues that cannot be addressed in isolation from the country’s interaction with the global economy.

The international dimension

It may seem a leap to move from examining declining industries and demographic trends to assessing Taiwan’s changing place in the world. But long-term solutions to Taiwan’s economic vulnerabilities reside just as much in the realm of international cooperation as in industrial policy. It is essential to encourage Taiwan’s diversification of trade and investment. But the country’s second-largest market—the United States—has failed to reduce barriers to Taiwanese exports, despite support in the US Congress for a free-trade agreement (FTA).57 Taiwan is in danger of being left on the sidelines as Asia-Pacific countries pursue regional arrangements that could facilitate greater trade; yet Taiwan’s place in electronics supply chains will be an important driver of future growth across the globe—giving it important leverage.

Beijing’s use of carrots (enticements like meetings with Chinese leaders, and the financial inducements of investment and lending) and sticks (economic coercion) in the realm of diplomacy has limited Taiwan’s entrée to regional trade arrangements— the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP).58 Even the Biden administration has excluded Taipei from its Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity (IPEF) because of concerns from other participating governments about China’s reaction.59

The issue is how Taiwan can use its advantages to benefit its economy and its trade partners. A large part of the answer lies in leveraging business linkages and unofficial diplomatic exchanges in tandem. It is an approach that has worked—however unsatisfying politically—despite the diplomatic isolation imposed by Beijing. Indeed, Taipei’s informal relations with the United States, Japan, Germany and other major countries are far more important than its formal ties to a dwindling number of small countries. China’s recent shift to aggressive diplomacy on a global scale has alienated many governments and offered Taiwan new opportunities to develop its informal relationships.

The evidence of Taiwan’s expanding trade and investment is already clear from India, where Foxconn is growing its assembly operations, to the United States and Japan, where TSMC is making major semiconductor investments. In the case of Japan, business bridges are accompanied by quiet government consultations and visits to Taiwan by ruling-party legislators and officials.60

Most governments look to Washington to take the lead in carving out new areas for interaction with Taiwan, and there are signs of progress. For example, the Biden administration has included Taiwan, Japan, and South Korea in the Chip 4 Alliance, which is aimed at coordinating export and technology transfer policies toward China.61

The United States has also taken the lead in building a Group of Seven (G7) consensus for responding to Beijing’s use of economic coercion. At their May 2023 summit in Hiroshima, the G7 leaders issued a statement in which they agreed—without mentioning China by name—“to coordinate, as appropriate, to support targeted states, economies and entities” facing such coercion. The language on “economies and entities” provides room to respond to actions affecting Taiwan.62

Another way in which Washington can provide concrete leadership at this stage is to show the way forward in broadening its economic dialogue with Taipei. Over the past two years, the Biden administration has reinvigorated bilateral interactions with Taiwan on issues ranging from a 2021 technology trade-and-investment framework agreement to an accord signed in June 2023 outlining a “21st Century Agreement” on nuts-and-bolts trade issues.63 Administration officials have described the agreements as part of a process that will run parallel to—and eventually outpace—the IPEF talks, which so far have produced an accord on supply-chain security. There is more to do.

Conclusion and recommendations

Over the past few years, the Taiwanese economy has weathered the COVID-19 pandemic and Chinese political and military threats because of its place in electronics supply chains. While Beijing has used economic coercion to bring pressure to bear on Taiwan, the unparalleled strength of the Taiwanese semiconductor industry—whose exports to China amount to hundreds of billions of dollars of chips a year—has reduced the impact of China’s coercive actions to annoyances. But while China’s economic dependence remains central to the cross-strait relationship, there is no guarantee that Beijing won’t decide in the future to sacrifice some of its economic well-being to bring real coercive pressure to bear on Taiwan.

Indeed, Taiwan’s reliance on the Chinese economy raises concern among the Taiwanese public and government officials, and rising costs and political uncertainty have caused Taiwan’s businesses to rethink their own dependence on the mainland. This dilemma led Tsai to push to shift trade and investment away from China and toward Southeast and South Asia. But it has been a slow transition, especially without significant government financial support. This challenge becomes even more important as other sectors of the Taiwanese economy show signs of losing dynamism and the inexorable aging of Taiwanese society raises warning flags about the country’s future.

Nonetheless, the move away from China has begun to build, in part, because of pressure from multinational business partners to reduce the risk of exposure to China. As this paper documents, Taiwan’s exports and investment in other Asia-Pacific countries are both now on the rise. But Taiwan should not be expected to make this transition on its own. Its international partners—who, despite the formal diplomatic isolation imposed by Beijing, have become more vocal in their support in recent years—must facilitate Taiwan’s continued integration into the global economy. It is essential that the United States take the lead in supporting and expanding upon this effort, not least by working with its allies to ensure that Taiwan is given a more prominent role as an economic leader in the Asia-Pacific region.

To that end, there are several steps that the next Taiwanese government and the Biden administration can take.

Recommendations for Taiwan

Regardless of the outcome of the January 2024 election, the new Taiwanese president will have an opportunity to review and recalibrate the government’s ongoing efforts to reduce Taiwan’s reliance on the Chinese economy and to seek new drivers of growth.

Strengthening the New Southbound Policy: The progress made to broaden economic ties with the Asia-Pacific region has been driven by market pressures and geopolitical tensions. But Taiwanese business executives regard Taipei’s concrete—as opposed to rhetorical—support for the campaign as sporadic, with financial incentives largely lacking.64 One area where significant government support has been available is in attracting factory investments back to Taiwan, but Western multinationals have undermined this program by asking their Taiwanese partners to invest away from Taiwan out of concern about a military conflict with China. Along with incentivizing domestic investment, Taipei should devote far more resources to its Exim Bank than the NT$10 billion reported to be under consideration by 2027.65

As part of the drive to build economic ties elsewhere in Asia, Taiwan also needs to focus more on turning business bridges into diplomatic partnerships. Many governments are more open to interacting with Taiwan despite Chinese economic coercion. But Taipei needs to be more opportunistic in pushing on an open door in a slow-growth, post-pandemic global economy. For example, the government should be working with India and Southeast Asia to develop Taiwanese industrial parks for companies moving supply chains. Moreover, the government should turn its largely ad hoc response to China’s economic coercion into a high-profile element of its effort to expand trade ties in the region, thus gaining political advantage at China’s expense.

Supporting New Industries: The Tsai government has had the foresight to push a vision for transforming Taiwan’s domestic economy. Its plans offer a blueprint for injecting new dynamism into an economy that increasingly appears to rest on the laurels of its extraordinary success in semiconductors. But today’s flagship technology can become tomorrow’s sunset industry, and Taiwan needs to give much more support to future successes.

Innovation is expensive—witness the vast sums that TSMC and other semiconductor companies spend on maintaining their competitiveness—so Taiwan must be prepared to devote real resources to the R&D and capital investments required by AI, biotech, and other industries. In addition, the government needs to provide the incentives for more foreign companies to base their research labs in Taiwan in partnership with local companies. Finally, it is essential to reform Taiwan’s immigration laws to encourage more foreigners—especially scientists and technicians— to work and settle in the country. It is only through immigration that Taiwan can reverse demographic decline and potential economic stagnation.66

Recommendations for the United States

US support for Taiwan, especially defense assistance, provides a bulwark against Chinese threats. The Biden administration has brought a renewed focus on deepening bilateral economic ties and facilitating Taiwan’s regional economic integration, which lagged under the two previous administrations. However, the administration’s efforts to launch initiatives to reinvigorate economic and business ties—with the exception of encouraging TSMC’s investment in two semiconductor factories in Arizona—have not been commensurate with the political consensus in Washington for a deeper bilateral relationship. There are several steps that the United States can take to strengthen that relationship—and encourage Taiwanese ties with other countries.

Strengthening US-Taiwan Economic Relations: A key pillar of support for Taiwan’s economic rise during the 1970s and 1980s was its access to the US market and US investment capital. But that success story increasingly has been written in the China market, as Taiwanese companies expanded investment and trade to the mainland. The next stage of Taiwan’s economic development—and its long-term security— requires a US-Taiwan FTA. However, the Biden administration has not yet been willing to move in this direction despite bipartisan congressional support—in large part because of the administration’s concern about the reaction from trade unions aligned with the Democratic Party.67

In the absence of a free-trade arrangement, it is essential that the Biden administration devote greater energy to the patchwork of bilateral negotiations with Taiwan that have so far produced agreements related to nuts-and-bolts trade procedures, technology collaboration, supply chains, and intellectual property protection.68 All of these are useful steps, but the administration has so far failed to enunciate a strategy that ties these disparate issues together.

The US-Taiwan Initiative on 21st Century Trade, signed in May 2023, offers an outline for closer economic ties, but the Biden administration still needs to publicly flesh out a clear vision for closer cooperation. As Ryan Hass, Bonnie Glaser, and Richard Bush suggest in their recent book on US-Taiwan relations, the 21st Century Agreement could offer a way forward by “taking a building block approach by establishing rules around emerging issues.”69 From Taiwan’s point of view, the incremental movement needs to point in the direction of an eventual FTA.70

At the same time, the Biden administration should introduce measures that respond to China’s economic coercion against Taiwan by offering products targeted by Chinese sanctions preferential access to the US market. The US Export-Import Bank and other government agencies also could begin working with the Taiwanese government to support Taiwanese businesses experiencing Chinese coercion through export credits, purchase commitments, and trade insurance.

Facilitating Taiwan’s Ties with Other Countries: The Biden administration’s recognition of Taiwan’s central role in semiconductor supply chains through its inclusion in the Chip 4 alliance is an important, concrete step in carving out new areas for interaction and cooperation with Taipei. But with Taiwan so far excluded from regional economic arrangements like the CPTPP, RCEP, and the Biden administration’s IPEF, it is essential that the United States provide more opportunities for Taiwan to expand its regional economic interactions.

It is noteworthy that the 21st Century Agreement with Taiwan was announced soon after the IPEF launch, with some goals of the two arrangements aligned. Kristy Tsun Tzu Hsu, a Taiwanese analyst, has called for Taiwan to seek “substantive cooperation” on IPEF issues under the 21st Century Initiative to “reduce the negative impact of not participating in IPEF.”71

By explicitly linking its bilateral agreements with Taipei to the IPEF agenda, and vice versa, Washington can help Taiwan broaden its cooperation with other Asia-Pacific governments and build stronger bilateral ties across the region. A case in point is the recent agreement among IPEF members on a supply chain “pillar” that calls for formation of a Supply Chain Council to coordinate policies on trade in critical sectors. This accord plays to Taiwan’s advantage in semiconductors and electronics, especially as multinational corporations accelerate their efforts to shift manufacturing out of China. The Biden administration should push for Taiwan to be granted observer status at the council to enhance regional cooperation in semiconductor trade, and it should seek to involve leading Taiwanese companies like TSMC in a proposed IPEF forum for corporate leaders.

It is in the interest of the Asia-Pacific region to take advantage of Taiwan’s critical role and competitive advantages in the global electronics industry and to foster its integration into emerging regional arrangements—either formally or in parallel with the efforts to build new frameworks for economic cooperation. Strengthening the web of regional ties will provide an important bulwark for Taiwan as it seeks to reduce its dependence on China and stake a claim to its rightful place in the global community.

No comments:

Post a Comment