Maria Siow

Take the most recent incident where Chinese ambassador to the Philippines Huang Xilian was said to have confronted and aggressively pointed at his host country’s armed forces chief, General Romeo Brawner Jnr, while saying “don’t provoke us”.

Describing Huang’s behaviour as “very hostile”, Philippine Senator JV Ejercito said in an interview with Filipino media on Tuesday that an ambassador should not be “disrespectful” and “rude”, especially to a high-ranking government official.

“Imagine, Huang is bullying our chief of staff … that’s probably another level of disrespect,” Ejercito said, adding that Beijing should recall the envoy.

Some Filipinos have called for the Chinese embassy and all consulates in the Philippines to be shut, while others suggested Manila should stop recognising the one-China principle, which states that Taiwan is part of China.

Bilateral tensions are understandably high, given the multiple skirmishes between their vessels in the South China Sea in recent months.

Over the weekend, videos released by the Philippine Coast Guard showed Chinese ships blasting water cannons at Filipino boats during two separate resupply missions. There was also a collision between Philippine and Chinese vessels at the Second Thomas Shoal.

The incidents prompted Manila to summon Huang, while lawmakers have called for the envoy to be expelled.

Even so, surely there is a better and more diplomatic way for Huang to convey his country’s position and concerns on the issue, rather than to resort to finger-pointing?

This is not the first time Huang has come under scrutiny for his behaviour. In April, he created an uproar when he suggested that thousands of overseas Filipino workers in Taiwan would be in danger if the Philippines does not oppose Taiwan independence.

Huang is also one among his many counterparts to have come under the radar for questionable diplomatic conduct.

In June, Chinese ambassador to South Korea Xing Haiming sparked controversy after warning his host country against making a “wrong bet” when it came to the Sino-US rivalry.

In May, Toronto-based diplomat Zhao Wei was expelled by Canada after being accused of involvement in a campaign to intimidate a Canadian opposition legislator critical of Beijing.

South Korea’s Finance Minister Choo Kyung-ho (left) with Chinese Ambassador to South Korea Xing Haiming during their meeting in Seoul, South Korea, in May.

A month earlier, Beijing’s ambassador to France sparked outrage when he questioned the sovereignty of all ex-Soviet states. Lu Shaye said countries that emerged after the fall of the Soviet Union did not have “effective status under international law because there is not an international agreement confirming their status as sovereign nations”.

Last October, Chinese diplomatic staff in England were caught on video violently handling a Hong Kong-born man holding a peaceful protest on the grounds of the Chinese consulate in Manchester. Then consul-general Zheng Xiyuan not only admitted assaulting a protester but also argued it was his “duty” and any diplomat would have done the same.

In 2019, Lithuania’s foreign minister summoned Chinese ambassador Shen Zhifei over his embassy’s involvement in a counter-protest against supporters of Hong Kong’s pro-democracy movement. Lithuania said China’s officials in Vilnius had “crossed the line” by directing pro-Beijing hecklers and disrupting an expression of solidarity.

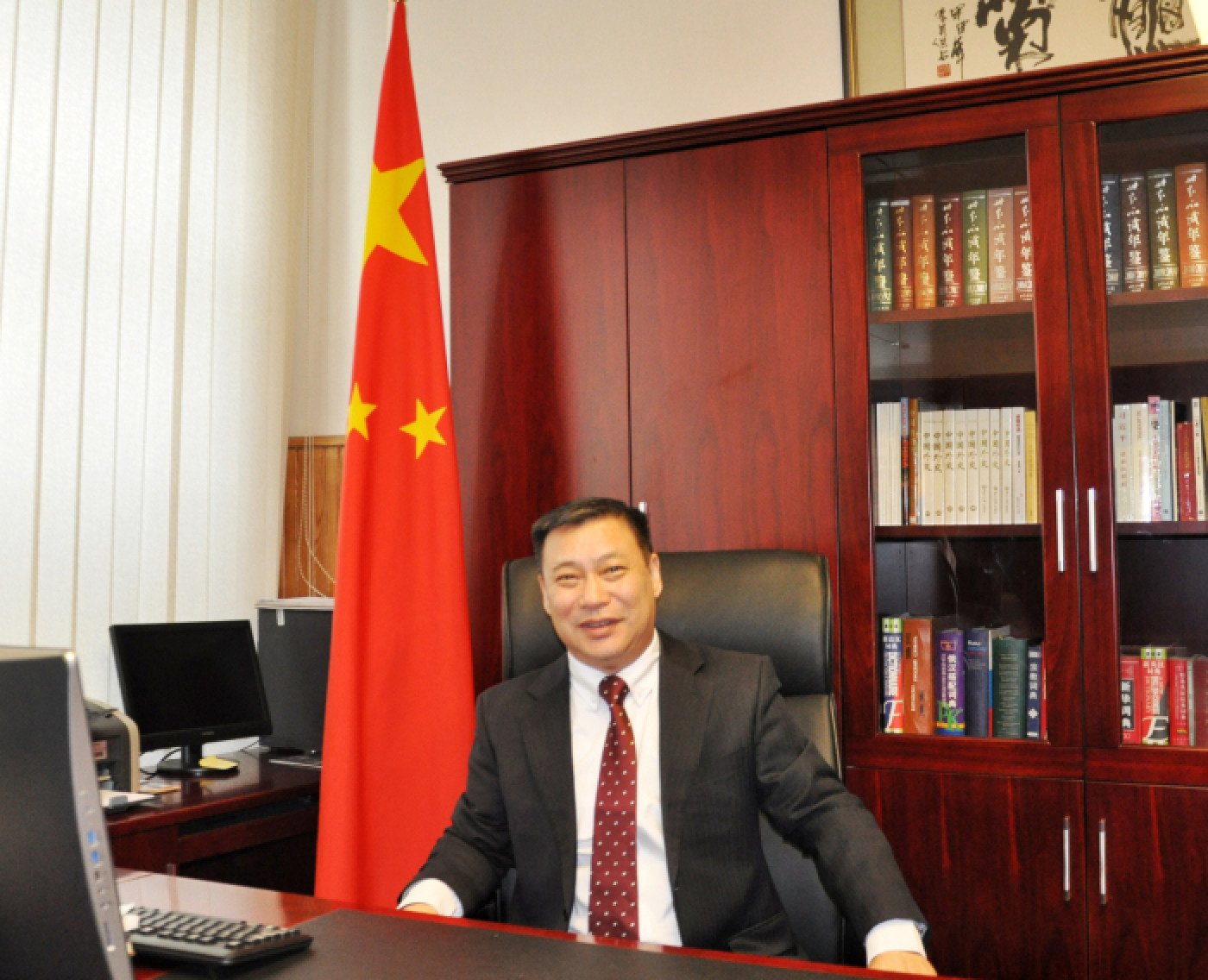

Chinese ambassador to Lithuania Shen Zhifei in 2019. Photo: Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in the Republic of Lithuania

Much has been said about “wolf warrior” diplomacy, which has led Beijing to assert itself more aggressively.

But with the geopolitical shift towards one that views China with greater suspicion and which places its moves under greater scrutiny, a shift away from such a form of diplomacy is unlikely to occur.

Indeed, an assertive and coercive form of diplomacy appears to be the new normal, as errant Chinese diplomats have clearly not been told off or reined in.

Apart from the recall of consul-general Zheng and his colleagues – ostensibly to avoid police questioning – few have paid the price for their behaviour in recent years.

In the case of the larger, especially Western, countries, these diplomats appeared to have scored political points, especially in the eyes of Chinese netizens.

But for smaller countries such as the Philippines, Chinese diplomats ought to bear in mind that their threatening behaviour will come across to many as a more powerful country “bullying” one who is less so.

It will also undo years of hard work undertaken by the Chinese leadership in pursuing the country’s neighbourhood diplomacy, which emphasises cooperation, partnership and friendship.

No comments:

Post a Comment