RALPH SAVELSBERG

In recent weeks, Israel announced that its Arrow missile defense system successfully intercepted ballistic missiles over the Red Sea on three occasions. These attacks were attributed to the Houthis, who control much of northern Yemen. However, the distance from their territory to Israel exceeds the performance of the Burkan-3, which was previously their known longest-ranged ballistic missile.

So, how could the Houthis possibly reach Israel? In September, the group displayed a new, larger missile during a parade in Sana’a. It is the obvious candidate, but is its range sufficient? The answers may lie in Iran.

A detailed look at the missile’s proportions and features indicates that it is practically identical to the Iranian Ghadr-F, for which Tehran claims a 1,950-kilometer range. Results of computer simulations and an analysis of a launch video show that this claim is plausible and that if such a missile were fired from north Yemen, it could reach all of Israel.

This is exactly the sort of missile that the Arrow system was designed to counter, but the attacks show that the Houthis are still expanding their ballistic missile arsenal, despite a UN arms embargo.

Arrows Hit Their Targets

In October, a few days after the Hamas attack on Israel, Abdul-Malik al-Houthi, the current leader of the Houthi movement, announced his support for the “holy jihad against the Zionist enemy” and threatened to participate in missile attacks if the US were to intervene in the conflict. Subsequently, on 31 October, the Israeli Defense Forces announced that an Arrow 2 had successfully intercepted a ballistic missile over the Red Sea. On Nov. 9 this was followed by a second announcement of a successful ballistic missile intercept, marking the combat debut of Israel’s Arrow 3 exo-atmospheric interceptor. Another intercept took place on Dec. 6.

In all three cases, Israeli media reported that the missiles’ intended target was Eilat, in southern Israel, and that Houthi-controlled Yemen was their likely origin. In all three cases the Houthis claimed responsibility.

The Houthi movement, also known as Ansar Allah, took over large parts of Yemen during the civil war that has been raging there since 2014, including its capitol, Sana’a. Since the 2015 Saudi-led intervention in the war, they have regularly lobbed ballistic missiles at Saudi Arabia.

However, until fairly recently, their longest-ranged ballistic missile was the Burkan-3 (Volcano), also known as the Zulfiqar. This is a development of the Soviet Scud missile, with a range of more than 1,200 kilometers. The US and the UN Panel of Experts on Yemen have implicated Iran in supplying such missiles to the Houthis, in violation of a UN arms embargo, with missile sections being smuggled into the country and reassembled locally. (In the past, Iran and the Houthis have denied allegations that Tehran is supplying the group with weapons.)

The increased range allowed the Houthis to attack Dammam on Saudi Arabia’s Persian Gulf coast in March of 2021. Moreover, in January 2022, they launched a missile at the United Arab Emirates. A US THAAD missile defense system intercepted it, in its first combat use. However, Eilat in Israel is approximately 1,700 kilometers from Yemen, far beyond the maximum range of the Burkan-3.

So the missile type most likely used in these attacks is a new, larger missile paraded through Sana’a in September. Labels indicate its name is Tufan, which means flood, deluge or storm.

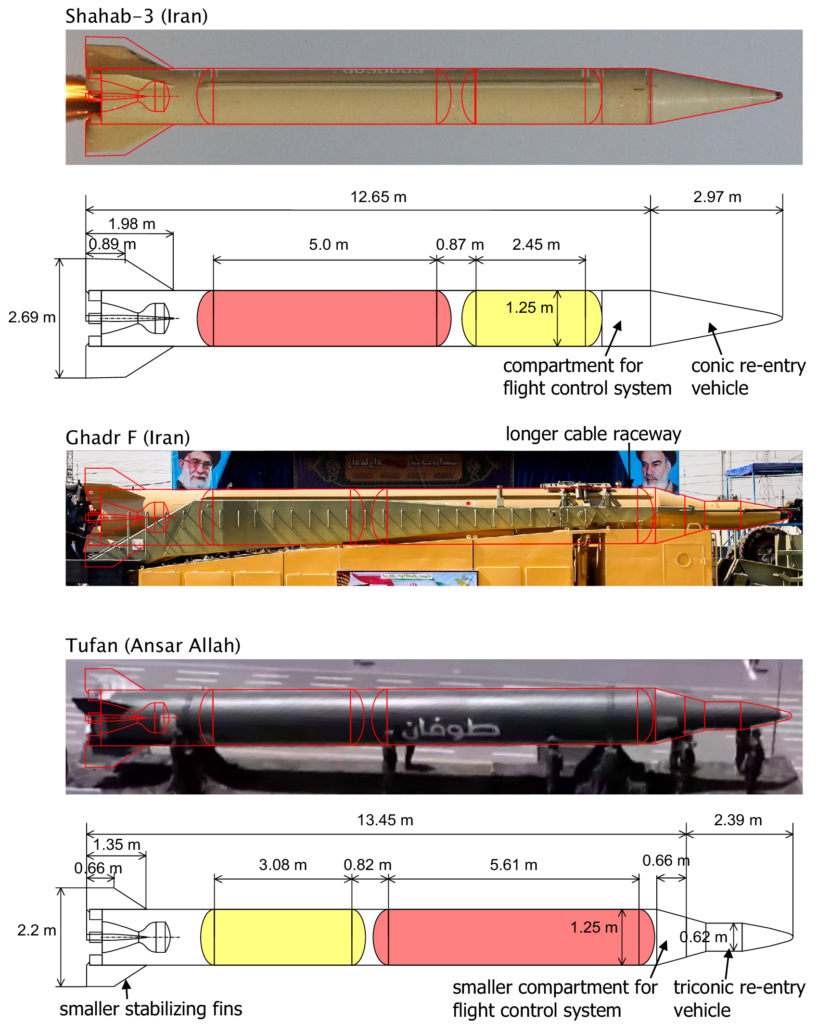

As has been reported elsewhere, it looks similar to Iranian missiles called Ghadr. A closer look at the Tufan and different versions of the Ghadr allows identifying the particular variant. The Ghadr variants are derivatives of the Iranian Shahab-3 (Meteor), which is a close relative of the North Korean Nodong. Originally, this most likely is a Soviet design related to the Scud, albeit considerably larger. It has a 1.25-meter body diameter, while the Scud’s is 0.88 meters. Its engine is similar to the Scud’s as well, but it too is larger and the position of the mounts for the engine attachment trusses on its combustion chamber is different. The Houthis also displayed the Tufan’s engine during the parade in Sana’a, and it looks identical to a Shahab-3 engine.

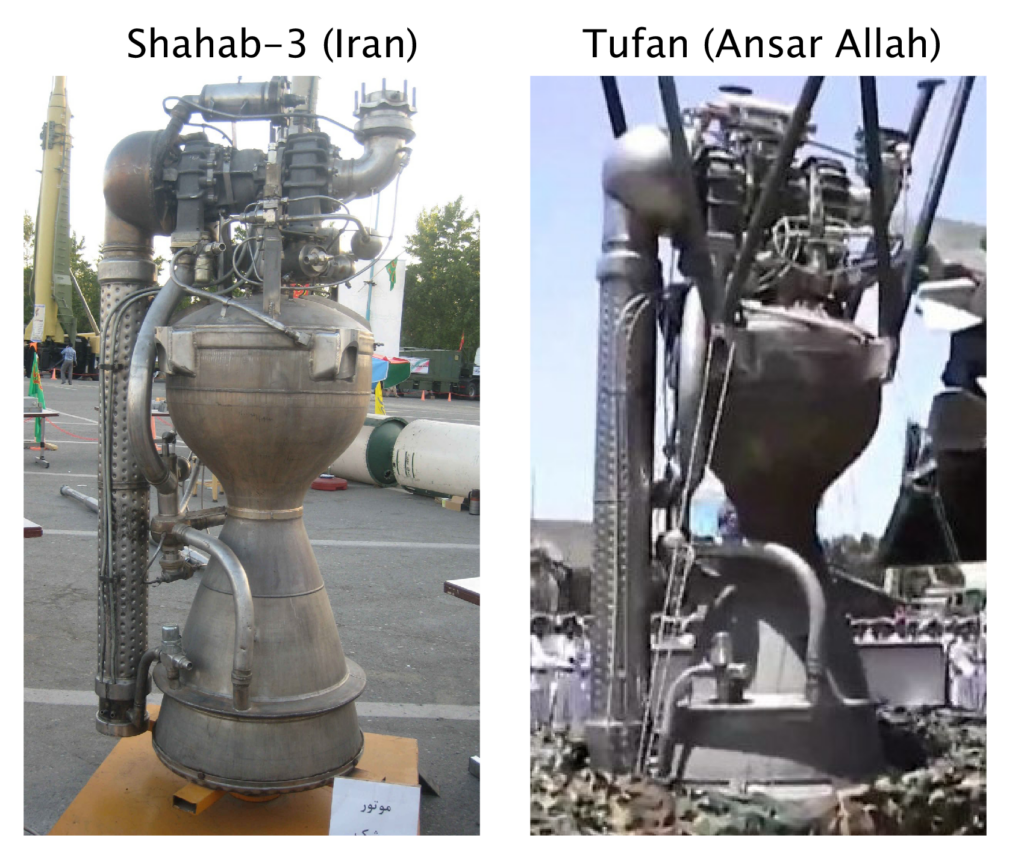

The engines for the Shahab-3 (left) and Tufan (right) are nearly identical. The Tufan display includes the engine attachment trusses.

Tufan Performance

The easiest way to increase the range of a ballistic missile, powered by a particular type of liquid-propellant rocket engine, is to increase the fraction of the take-off mass taken up by the propellant. Different ways of doing this are decreasing the warhead mass, increasing the size of the propellant tanks or reducing the mass of the empty missile — for instance by using a lighter material or by reducing the mass of the missile’s flight control system. The increased range of the Burkan-3, relative to the Scud, is likely due to all of these changes. The Burkan-3 also has smaller stabilizing fins reducing aerodynamic drag.

The Ghadr missiles are longer-ranged developments of the Shahab-3. The external properties of the Tufan match the Ghadr-F.

The Ghadr versions have increased ranges too, due to similar changes to the Shahab-3 design. Iran paraded a missile labelled the Ghadr-1 through Tehran in 2009. This had a smaller so-called triconic re-entry vehicle and a smaller guidance and flight control system in a smaller compartment. During subsequent parades, Iran displayed more extensively modified versions, labelled the Ghadr-F and Ghadr-H, that both are longer than the Ghadr-1 and with smaller stabilizing fins.

Their labels were not always consistent, but the length increase of one of them is largely due to longer propellant tanks. This is easily visible through long cable raceways that run alongside the tanks to the top of the cylindrical missile body. Iran claims maximum ranges of 1,750 kilometers and 1,950 kilometers for the Ghadr-H and Ghadr-F, respectively. Since the version with the longest tanks will have the longest range, this most likely is the Ghadr-F. The Tufan shares the small fins and long cable raceways and a comparison of the Tufan and the Ghadr-F shows that their proportions are practically identical.

There are links between Iran’s ballistic missile program and North Korea. The North Koreans have a Nodong variant similar to the Ghadr-1, with a short guidance section and triconic warhead. Furthermore, a Nodong version they launched in December last year, purportedly to test technology for their recent spy satellite launch, has smaller stabilization fins. However, no known North Korean Nodong variant has all of these features. Apparently, the Tufan indeed essentially is a Ghadr-F — so if Iran’s claims are true, it should be capable of flying 1,950 kilometers.

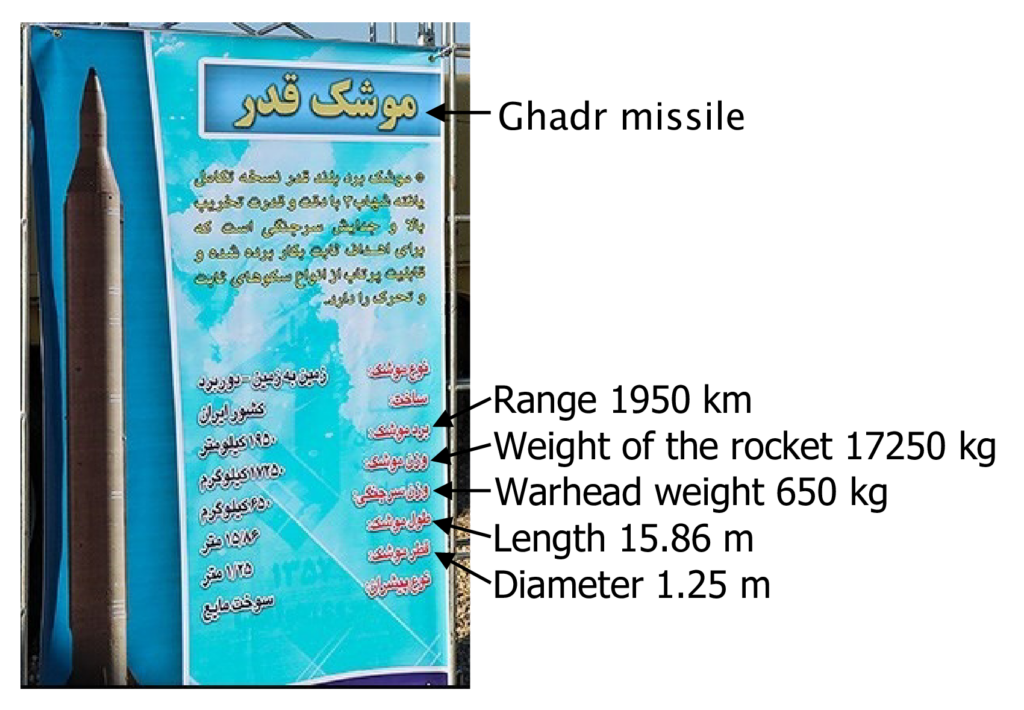

Ghadr data displayed in Iran.

Of course, the Iranians could be inflating its performance. Using computer simulations of missile trajectories, we can verify that it is plausible. During an exhibition in Tehran, Iran showed a poster with several specifications, including the 1,950 kilometer range and a 17,250-kilogram take-off mass, with a 650-kilogram warhead. The thrust of the Shahab-3 engine is known from open sources, as well as how much propellant it burns per second.

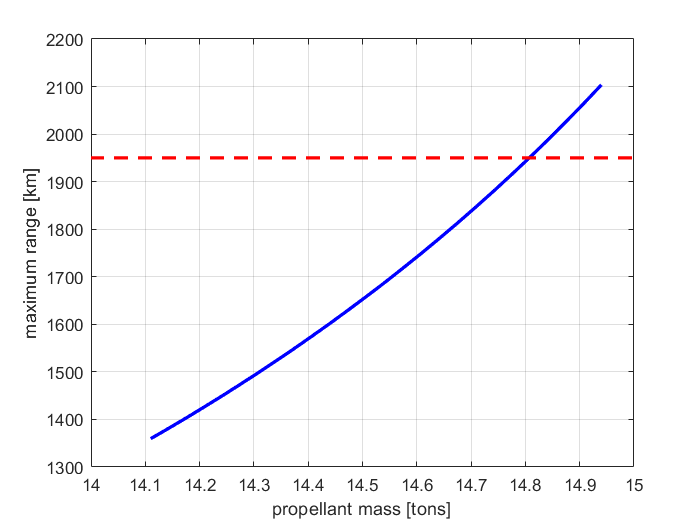

Simulated maximum range for the Ghadr as a function of the propellant mass, showing that 14.8 tons gives the claimed 1950 km range

Multiple simulations with this thrust and take-off mass, but with different initial propellant masses and the associated burn times, show that a 1,950 kilometer-range requires a propellant mass of 14.8 tons. An image of the Ghadr-F, taken during a parade, shows where the bulkheads of the propellant tanks connect to the missile’s outer skin, so that their volume can be estimated. Based on this, the missile’s propellant tanks are large enough, with a little room left to spare.

Housing 14.8 tons of propellant in a 17,250-kilogram missile does require a light missile airframe. The mass of the simulated booster at burnout is 10.8 percent of the booster take-off mass. This is smaller than for the Burkan-3, indicating that the Ghadr is relatively lighter, but it is comparable to more advanced liquid-propellant missiles. Therefore, the claimed 1,950-kilometer range is plausible if the missile indeed has a 17,250-kilogram take-off mass. If it were heavier, its range would be smaller.

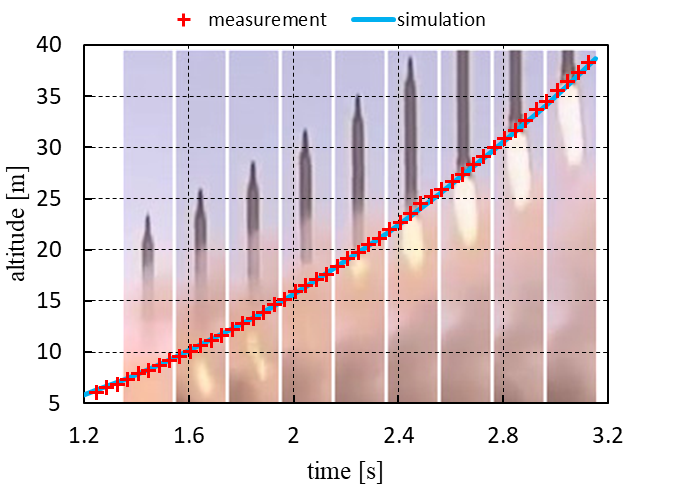

The measured position as a function of time from a video of a Ghadr launch (with one per five frames shown) agrees almost perfectly with simulation results.

The take-off mass can be verified using a launch video. During an exercise, a Ghadr (with a long cable raceway) was filmed, being launched from an undisclosed location in central Iran. With the frame rate known and a known length of the missile, we can measure the altitude it reached, relative to its launch altitude, as a function of time.

If has a 17,250-kilogram take-off mass, the measurements should match the simulation results. If it were heavier, it would gain altitude less quickly. The exact launch location is unknown and a complicating factor is that, at a higher elevation, the missile has more thrust. Since the average elevation of central Iran is approximately 900 meters, the simulation started at 900 meters. The result agrees almost perfectly with the measurements, so the 17,250-kilogram take-off mass is plausible too.

Maximum range against Israel from a launch site near Dhahyan, in northwest Yemen

From Yemen, such a missile should be able to reach further than Eilat. For maximum coverage of Israel, the Houthis could launch their missiles from the northwestern part of their territory, close to Saudi border, and in the past, the Houthis have launched Scud missiles from that area. According to the UN, in May of 2017 they launched a Scud from a field near Dhahyan, for instance. The terrain there has a high elevation, which increases the missile’s thrust and, additionally, reduces aerodynamic drag, increasing the range. Trajectories to Israel point slightly west, though, such that Earth rotation decreases the range. Simulation results that include all the relevant effects show that, from Dhahyan, all of Israel would be in range.

Israel claimed to have successfully intercepted all three missiles, and its missile defenses are tailored to counter this type of threat. Nonetheless, these attacks demonstrate the increasing range of the Houthis’ ballistic missile arsenal.

They do not have the industrial base for building these missiles themselves, so despite the arms embargo, such larger and increasingly capable missiles are still finding their way to Yemen, most likely from Iran. Furthermore, although pre-war Yemen had Scud missiles, it seems likely that they can only operate the newer Tufans with Iranian training and assistance.

No comments:

Post a Comment