Paul Goble

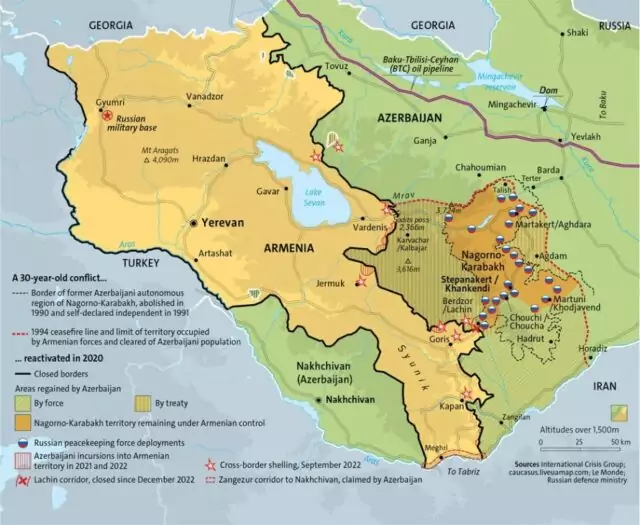

On November 28, Alen Simonyan, head of Armenia’s National Assembly, told journalists that “the ball is in Azerbaijan’s court” regarding peace negotiations between the two countries. He added, “Armenia fully supports the territorial integrity of Azerbaijan. … If desired, the peace agreement can be signed within the next 15 days if the government of Azerbaijan demonstrates [real] political will” (AzerNews, November 28). The international community has long insisted that the solution to the Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict lies in the restoration and recognition of the Soviet administrative borders between the two republics. Yerevan and Baku, under pressure from the West, have edged toward a solution along these lines, which would involve swapping their respective exclaves. Russia, however, is wary that such an arrangement could finally lead to a comprehensive peace agreement between the two sides, which could further disrupt Moscow’s influence in the South Caucasus.

The Armenian and Azerbaijani exclaves came about during Soviet times as a means of Moscow asserting and maintaining its administrative control. Until the disillusion of the Soviet Union, there were eight Azerbaijani exclaves inside Armenia subordinate to Baku and two Armenian exclaves inside Azerbaijan under Yerevan’s control, despite each being surrounded by the territory of the other. The exclaves were small: the Armenian ones totaled only 124 square kilometers, while the Azerbaijani ones totaled only 50 square kilometers, typically encompassing a single village or group of villages. This led to the exclaves being ignored by outsiders until now, though these regions have remained symbolically important to both Armenia and Azerbaijan (Stoletie, October 28; Newsarmenia.am, November 18; Gazeta.ru, November 24).

The former Armenian or Azerbaijani residents fled these exclaves in large numbers as the conflict intensified between Yerevan and Baku and military forces on both sides began to occupy these areas. Today, these exclaves contain few, if any, residents of the nationality that led to their creation due to the ongoing conflict over the past three decades. As a result, many believe that these exclaves must be returned to their original countries due to legal precedent and national pride. These supporters take heart from the insistence of the international community that a peace agreement between the two countries must be based on the restoration of the 1991 borders (Eurasianet, August 3, 2021; Window on Eurasia, August 7, 2021; Zerkalo, May 10, 2022)

The issue of transferring these exclaves is attracting increased attention both in the region and, to a lesser extent, internationally. Some observers stipulate that the status of these exclaves is closely tethered to any lasting peace agreement. Others worry that the restoration of these exclaves to their national status before 1991 or an exchange of the exclaves could destabilize the situation, possibly becoming the basis for future conflicts between Armenia and Azerbaijan. In a wider sense, the swapping of exclaves between Baku and Yerevan could set a precedent for the resolution of the status of 40 additional exclaves throughout the post-Soviet space. Thirty of these exclaves can be found in Central Asia, where they continue to spark violence.

Since the end of the Second Karabakh War in November 2020, the issue of what to do with Armenia’s and Azerbaijan’s exclaves has moved from the margins to center stage (YouTube, July 21, 2021; Kavkaz Uzel, November 3, 2021, December 24, 2021; Window on Eurasia, February 12, 2022). Azerbaijan’s restoration of full control over Karabakh has further elevated the need to fully resolve the situation. On November 24, Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan said as much and indicated that his earlier calls for the exchange of these territories would serve as the foundation for a broader peace agreement (Zerkalo, June 14, 2021; TASS, November 24).

Russian and Armenian commentators suggest that Pashinyan’s statement and his continued promotion of an exchange of territory will inevitably undermine his position in Armenia. They argue that such sentiments could raise troubling discussions about future exchanges of territory within the South Caucasus, including the revival of talks about the transfer of control over the Zangezur (Syunik) Corridor from Armenia to Azerbaijan. Additionally, Moscow is anxious that the swapping of exclaves could become a dangerous precedent for the resolution of other border disputes in Central Asia and, more generally, in the post-Soviet space (Vzglyad, November 25). Pashinyan has put himself in an increasingly untenable position politically, in which he is being heavily criticized by those Armenians who fled Karabakh. In contrast, his pursuit of an accord with Baku has pleased many in the international community. Some commentators point out that, though a simple territorial swap would give Armenia more territory than it would Azerbaijan, many Armenians view any further yielding of Armenian territory as completely unacceptable and a threat to the country’s future, even if doing so would facilitate a peace treaty (Vzglyad, October 11).

In agreeing to the principle of an exchange of territory, Pashinyan has exacerbated the conflict over the opening of the Zangezur Corridor. The corridor connects Azerbaijan proper to the Nakhchivan exclave, passing through Armenia’s Syunik Oblast. Some analysts have argued that the opening of this corridor could trigger a new war by reopening the possibility for territorial exchanges. This idea was widely talked about shortly after the fall of the Soviet Union. At that time, some proposed that the two countries could resolve their differences if Baku yielded Karabakh, which had an Armenian-majority population, to Armenia in exchange for Armenia yielding the Zangezur Corridor to Azerbaijani control (Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, June 8, 2000; see EDM, October 11).

Russian commentators, in particular, are worried that a territorial swap leading to a peace treaty between Armenia and Azerbaijan would be detrimental to the Kremlin’s presence in the South Caucasus. They worry that a peace agreement would reduce Russian influence by eliminating the frictions between Baku and Yerevan that Moscow has routinely exploited and highlight the West’s growing influence in the region. Perhaps even more so, Russia fears the broader impact that peace in the South Caucasus could have on Central Asia, where Soviet-era exclaves are the most numerous and the sites of serious border disputes. The resolution of the Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict—especially if it involves the swapping of exclaves—could trigger a significant decline for Russian influence not only in the South Caucasus but in Central Asia as well.

No comments:

Post a Comment