Michael Rubin

Few defend the Islamic State. The group was cruel. They enslaved minorities, raped women, and tortured children and men. They tossed suspected gays off tall buildings and executed young men for infractions as minor as smoking a cigarette or watching a soccer game.

Still, the fight against them was not easy. In 2014, the group seized Mosul, a city the size of San Diego. It made its capital in Raqqa, a Syrian city the size of Miami.

Five years later, I visited both cities. Both had been free from the Islamic State scourge for more than two years, but still lay largely in ruins. To access Raqqa required passing miles of the empty shells of what once were apartment buildings. Every few blocks, piles of rusted vehicles lay stacked nearly a dozen high.

The Islamic State did not level Raqqa; American bombardment did. Syrian Kurds fought alongside U.S. troops, going block-by-block to rid the town of the Islamic State.

Because of their sacrifice, life had started to return to Raqqa. A youth soccer team scrimmaged in the stadium that just a couple years previously the Islamic State used as a prison and torture center. Some stores in the market had opened, selling falafel and fruit, wedding gowns, toys, and school supplies.

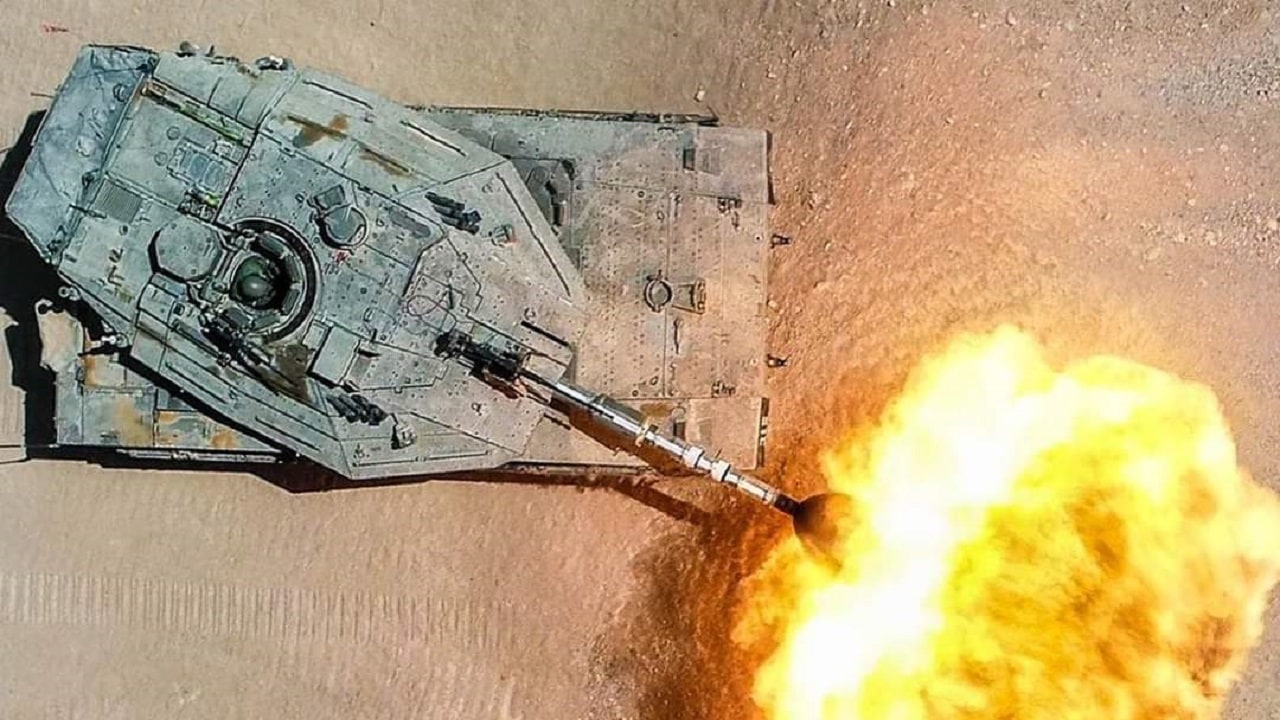

Mosul was in bad shape, too. Again, it was not the Islamic State that destroyed the city, but rather the urban fighting necessary to liberate it. Aerial bombardment, artillery barrages, and door-to-door fighting destroyed more than 130,000 houses. The Islamic State was ruthless. Several houses bore the telltale signs of suicide bomber detonation.

At the height of the Battles of Raqqa and Mosul, civilians trapped in both cities suffered. Food and water were in short supply. There was little medicine. Electricity was out for days. Neither residents nor the international community demanded the Syrian Kurds, Iraqi Army, or their American partners stand down to allow international organizations to establish humanitarian corridors. Momentum mattered. To allow Turkey to ship emergency supplies would mean helping the Islamic State at the expense of the civilians the group terrorized. Even a cease-fire would allow the Islamic State to regroup, reorganize, and seize human shields. Residents suffered, but they also understood that there could be no middle ground in the fight to eradicate a terrorist group. When facing a beehive, the worst option is to whack it with a stick and then take a pause to allow the hornets to escape.

This brings us to Gaza. There is little difference between the theology professed by the Islamic State and that of Hamas. The Islamic State’s dismissal of national borders, and Hamas’ rhetoric tying itself to a Palestinian national movement, might signify slightly different goals, but not different theologies. Both groups evolved from the Muslim Brotherhood’s more virulent and extreme wings. While the Islamic State singled out Shiites and Yezidis, while Hamas castigated Jews, on a day-to-day basis, it was the Sunnis under the control of each who suffered the most.

When American politicians, self-described human rights or peace activists or, for that matter, UN Secretary General António Guterres call for a ceasefire, then, they must explain whether they would have made the same demands of those seeking to free Iraq and Syria from the horror of the Islamic State. Would midlevel U.S. State Department foreign service officers put American troops in danger with calls and leaks demanding a cease-fire? As for Guterres, he became secretary-general in the midst of the Battle of Mosul and before the final Battle of Raqqa. Could he explain why he demands Israel stand down when he made no such demand of those waging a far less precise and more destructive campaign on cities larger than Gaza?

War is hell, and urban combat even more so. Still, the juxtaposition of the international sympathy for efforts to defeat the Islamic State with the reticence to allow Israel to take the same actions shows stunning hypocrisy.

No comments:

Post a Comment