Devika Shanker-Grandpierre

Introduction

The trajectory of left-wing extremism (LWE) in India has fluctuated, transitioning from once being considered the foremost internal security threat to now appearing to be in decline. At its peak in 2006, the European Foundation for South Asia Studies estimated Maoists to be an estimated 20,000-strong group, occupying territory in states that comprised 20% of the country’s population. LWE incidents decreased from 2,258 to 509 between 2009 and 2021. What led to their rise and fall?

In this Insight, the focus will be placed on People’s March, a banned Maoist publication which played a crucial role in disseminating the ideologies, goals, and activities of the CPI (Maoist) Party and the broader Maoist movement in India. Since the CPI (Maoist) is designated as a terrorist organisation, understanding their communication strategies through the People’s March can provide insight into their efforts to gain influence in the subcontinent – both online and offline.

Roots and Evolution: Ideological Origins to Armed Struggles

Between 1965 and 1967, Charu Mazumdar, a dissenting voice among the CPI (Marxist) Party, articulated a theoretical framework for the Indian armed revolution in a series of documents now known as the ‘Historic Eight documents’. This framework evolved into guerrilla warfare aimed at undermining grassroots governance by assassinating lower-level government officials, law enforcement personnel and others to create a leadership void and mobilise the local populace.

In 1967, a clash in Naxalbari, West Bengal, resulted in the deaths of 10 peasants and led to the expulsion of dissenters from CPI (Marxist). This event led to the creation of the Communist Party of India (Marxist–Leninist) Liberation (CPI (ML)), which eventually became the CPI (Maoist) party in 2004, also known as ‘Naxals’ or ‘Maoists’. They became a prominent left-wing extremist (LWE) presence in India, a designated terrorist organisation responsible for numerous violent incidents causing casualties among civilians and security personnel.

Strategic Manoeuvres: Shaping Public Perception

This section explores the strategies employed by extremist groups to shape public perception and ensure their sustainability through effective funding mechanisms.

One critical approach is the image projection strategy, as exemplified by Charu Mazumdar, who advocated a self-sacrificing and ascetic image of the revolutionary Indian man. This idealistic portrayal instils a sense of identity and significance among Maoist members, drawing parallels with Atran’s concept of ‘suicide terrorism’.

Another tactic is the integration strategy, disclosed by former extremists arrested between 1960-80. LWEs engaged in local meetings with villagers, empathising with their grievances and attributing problems to external forces or perceived enemies. By doing so, these groups provided a narrative that channelled the population’s frustration toward political ideologies and armed struggle, resulting in villagers offering protection to the activists during state crackdowns against extremist activity.

They also conduct offline outreach through printed materials like pamphlets, posters, and periodicals, often left at violent scenes to instil fear. This modus operandi remains unchanged even today. During periods of peak Maoist activity, platforms like People’s March were used for disseminating LWE views on issues such as land rights and socio-economic equity. Extremist groups also since transitioned to using encrypted communication channels and Very High Frequency (VHF) sets to avoid detection. Monetary mobilisation methods include extortion from mining industries and NGOs, generating substantial annual funds. Maoists charged levies on non-governmental organisations and projects, even blocking developmental initiatives in their areas. They also reportedly use the bank accounts of villagers who support them to evade detection.

Deconstructing LWE Communication strategy through ‘People’s March

This section examines the mechanics underlying the communication strategies employed by LWEs in India, focusing on the illegal publication, People’s March. Analysing 43 offline and online editions since 2003, this framework aims to assess the thematic narratives through which People’s March and similar publications amplify their extreme left-wing ideological reach.

Framing the Enemy

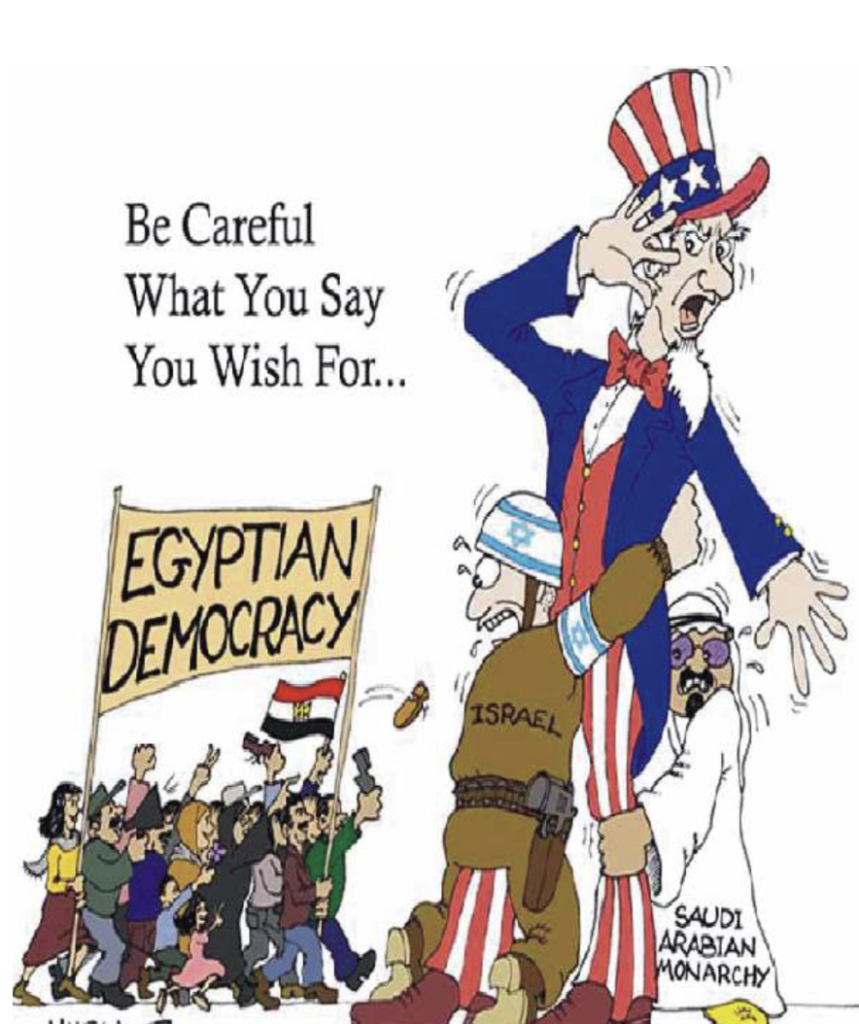

The authors aim to establish an ‘us versus them’ dynamic by highlighting differences in the values and objectives of the perceived enemy. The authors employ a powerful visual strategy through cartoons to highlight the stark power disparity between the perceived enemy and ‘ordinary’ people. These cartoons often portray the enemy as larger than life, symbolising luxury, wealth, and authority. On the other hand, the people are depicted as diminutive in size and impoverished, symbolising their vulnerability and lack of resources. This visual framing effectively conveys that the enemy benefits from their privilege and wealth at the expense of the marginalised and underprivileged population. It serves as a powerful commentary on social injustice and inequality, using the medium of cartoons to engage and provoke thought on these critical issues.

In 2011, the Egyptian democratic movement, part of the broader Arab Spring uprisings, had complex interactions with the United States, the Saudi monarchy and Israel. Arab Spring complicated the U.S.-Saudi relationship and the U.S.-Israel relationship by bringing to the forefront the tension between U.S. support for democratic movements and its longstanding alliance with regional regimes.

Fig. 1: Cartoon from People’s March (January 2011)

Fig. 1 depicts Uncle Sam, Israel, and Saudi Arabia clinging to its legs, while a banner titled ‘Egyptian Democracy’ is held by a marching group titled ‘Be Careful what You Say You Wish For’. This phrase and the visuals imply a sense of caution and the idea that promoting democracy may lead to outcomes that the US did not anticipate or desire in terms of regional dynamics and relationships.

In June 2005, Pranab Mukherjee, then India’s Defense Minister, and Donald Rumsfeld, the US Secretary of Defense at the time, signed the ‘New Framework for the US-India Defence Relationship’. The framework aimed to strengthen defence cooperation between the two countries over the following decade. It included provisions for military exercises, defence technology transfers, and collaboration on security issues. One of the critical aspects of this agreement was opening opportunities for India to acquire advanced US defence technology and equipment. This was a significant shift in US policy, as it signalled a willingness to engage in defence trade with India, which had traditionally relied on Russian arms.

Fig. 2: People’s March cartoon (August 2005)

Fig. 2 shows a cat symbolising America with gleeful mice around a desk, offering ‘Poison’ and ‘Coffin’ options; titled ‘Defence Pact for World Mice Miyuav Corporation’. The cartoon uses mice to symbolise the impoverished population and portrays entering a defence contract with the ‘cat’ (representing the United States) as a risky choice, implying that the US might be seen as a potentially predatory force, putting Indian people at a disadvantage. In the August 2005 issue, the authors expressed significant concerns regarding the potential consequences of the agreement. They feared that it could lead to heightened US involvement and possible military engagements, resulting in the loss of Indian lives.

Moral Justification and Glorification of Violence

People’s March also employs a narrative that frames Maoist violence as a response to oppression, positions them as heroic figures, and implies that their actions are morally justified in their ideological struggle.

For instance, the August 2006 issue asserts that in the face of injustice and oppression, violence may become necessary to improve people’s livelihoods and empower them, emphasising the importance of clear and just means. Various other magazine issues (December 2012, August 2007, June 2005) condemn harm to innocent people but raise doubts about the effectiveness of peaceful alternatives. Collectively, these perspectives form a nuanced stance on violence in pursuing perceived justice and empowerment for marginalised populations. The fusion of emotional engagement and ethical appeals creates a potent tool for conveying their message.

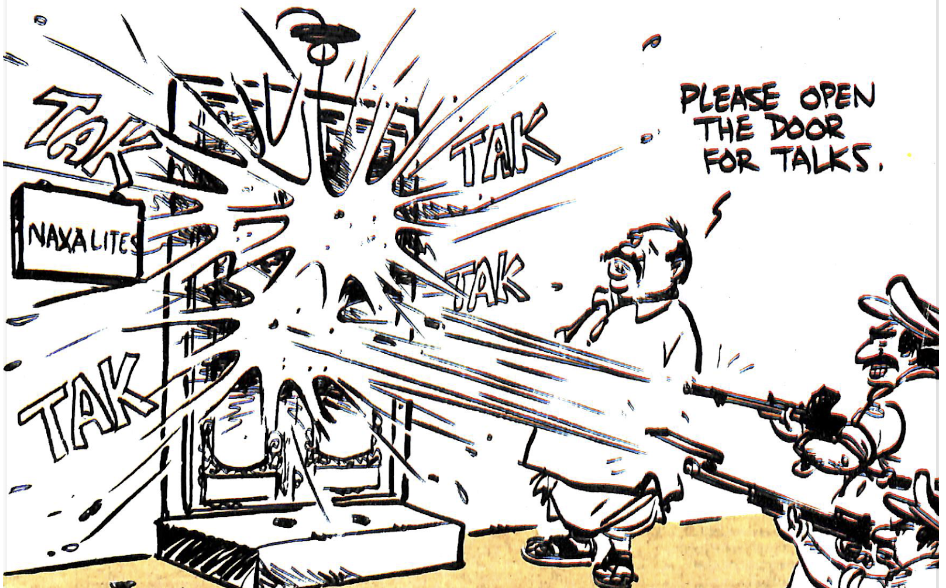

One example of this narrative is exemplified in a cartoon (Fig. 4) where police officers are shown firing at a closed door with Maoists inside. At the same time, a politician urges them to “Please open the door for talks.” This stark contrast implies that the state, represented by the police, resorts to violence, while the Maoists are depicted as open to negotiation. This portrayal suggests that the Maoists are driven to violence in response to state aggression, framing their actions as self-defence or a last resort.

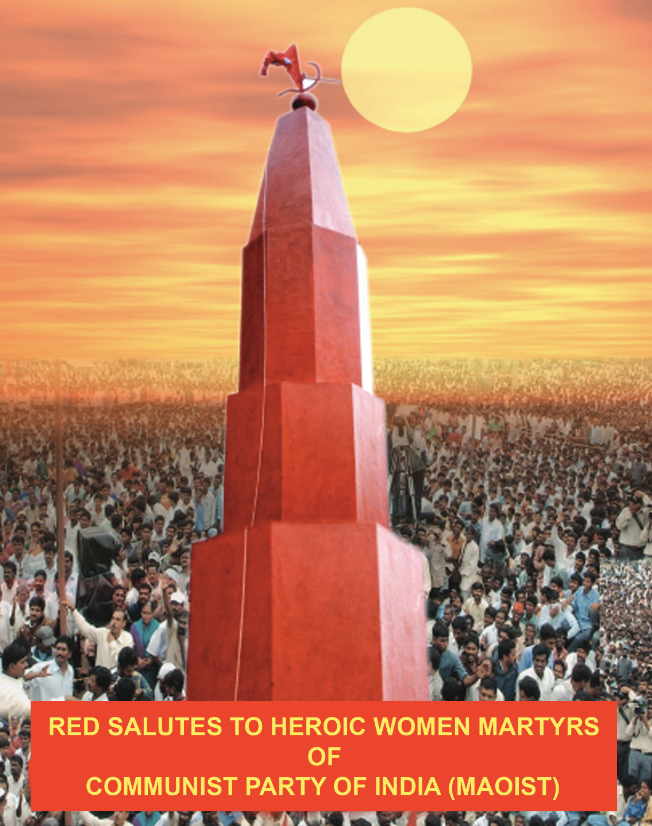

In another instance (Fig. 5), the tagline “Red salutes to Heroic women martyrs of Communist Party of India” explicitly praises and glorifies the Maoist fighters, presenting them as heroes and martyrs. This justifies their actions and elevates them to a morally superior position, implying that their violence is rationalised by their pursuit of equality.

Fig. 4: Cartoon from People’s March (June 2005)

Fig. 5: Cartoon from People’s March (August 2007).

Another recurring sub-theme in several editions (April 2007, April 2011, September 2006) of People’s March portrays the authors as opponents of environmental exploitation. They argue that their actions, including acts of violence, respond to the perceived exploitation and environmental harm caused by government and corporate interests. This narrative fosters empathy and solidarity with the marginalised communities impacted by these activities, specifically focusing on women who, as ‘mothers’ of the earth, are at the forefront of the fight despite being ‘raped and murdered’.

The Online Footprint of People’s March

In this section, we delve into the intricate web of People’s March’s online presence and explore the sources that amplify its digital reach. We uncover some intriguing insights by analysing the backlinks associated with the magazine’s primary website links.

Diverse TLD Registrations

People’s March employs a strategy of registering with multiple Top-Level Domains (TLDs), all redirecting to the main website. This approach serves several purposes, including localising content, projecting a global presence, and potentially diversifying its traffic sources.

Uniform Content Across Multiple Domains

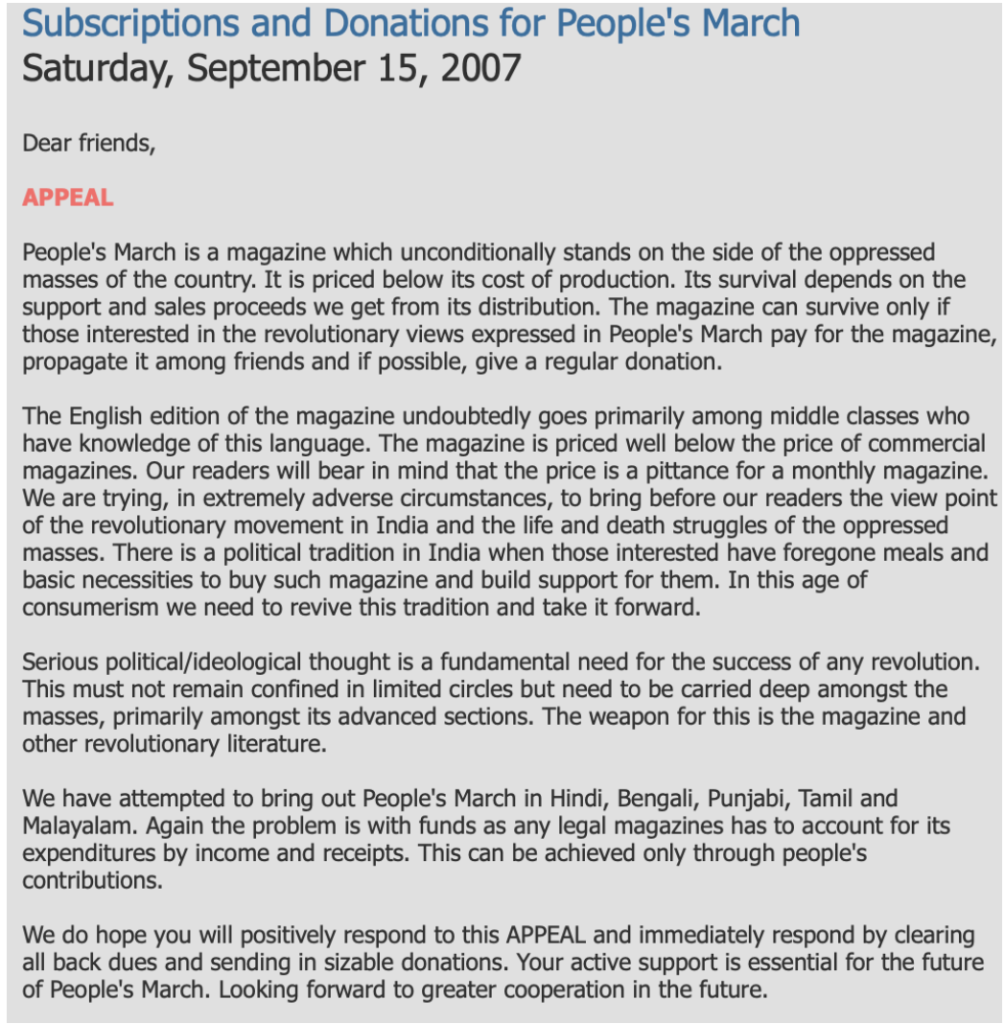

By examining backlinks, we discover that multiple domains, each claiming to be an independent activist/news source, share identical sequences of content published on the same exact dates as People’s March. This phenomenon implies a replication of content across various domains (Fig. 7 & 8).

Fig. 7: On September 15, 2007, People’s March and another domain posted identical calls for donations, with many backlinks connecting them.

Fig. 8: On April 5, 2008, People’s March and another domain shared identical content with instructions on how to send financial support.

Direct Amplification

Digital platforms contribute minimal direct traffic to the primary domains. This result is not unexpected because of the strict regulations in India. The Indian government consistently makes numerous requests for action on digital platforms, and they have dedicated departments focusing on this. These requests have been on the rise year after year.

Indirect Amplification

The magazine’s amplification is facilitated through endorsements by various international entities. These entities can be identified through their use of non-Indian/non-English language and registration information. These entities receive substantial traffic directly from digital platforms and, thus, indirectly to the magazine. A notable example is the extensive linkage between one of the primary People’s March domains and a US-based domain, connected by over 24.8k links. This US-based domain has received an impressive 6,008,843 referrals through digital platforms. Another example is from an IT-registered domain with >11k referrals, linking to People’s March. This suggests that the reach and impact of People’s March extend beyond India’s borders, finding resonance with entities worldwide who endorse its content and objectives.

Counterstrategy: Government Responses to Extremist Narratives

This section examines the counter-strategies harnessed by the Indian government to counter extremist narratives and ideologies, explicitly focusing on the contextualised framework of the People’s March magazine.

Development Initiatives & Perception Management

The government has strategically employed regional media advertisements and radio jingles, using the slogan “Who is against development?” as a rhetorical tool to challenge public perception of anti-state sentiment. These government campaigns challenge far-left extremist narratives by highlighting the destruction of educational institutions and critical infrastructure by violent Maoist extremists.

Rights, Entitlements and Rehabilitation

The LWE Surrender and Rehabilitation Scheme provides LWEs with financial incentives, vocational training, and psychological counselling in return for surrendering their weapons and renouncing their ideology. This initiative facilitates the reintegration of militants into mainstream society, undermining the appeal of armed insurgency.

Conclusion

Despite the decline in fatalities, researchers and technology companies should remain concerned about LWE in India for several reasons:

Persistent Threat

Although fatalities associated with LWE have decreased, groups continue to exist and operate in India. The ideology that drives these groups remains potent and can resurge under favourable conditions, especially in the upcoming Indian elections in the Maoist-affected regions. Tracking and moderating becomes challenging in cases like the People’s March publication, where content is replicated across multiple domains with diverse TLDs. Identical content on different domains may circumvent moderation efforts and remain accessible to users violating local regulations.

Global Implications

LWE groups can have international connections and ideological affiliations. Their activities can spill over borders, making them a concern not just for India but for other countries as well. Digital platforms face the challenge of identifying and assessing the influence of these networks and determining whether they are engaging in legitimate or harmful activities in totality. The presence of international support for content that may be proscribed or considered extremist in one country but not in another further complicates the issue.

To effectively counter the spread of extremist ideologies, researchers and tech companies can take the following actions ahead of upcoming Indian elections in affected regions:

Amplify Counter-Narratives

Collaborate with governments and regulatory bodies to develop and disseminate counter-narratives that challenge the extremist ideologies propagated by LWE groups. This partnership can amplify government initiatives aimed at perception management, ensuring they reach their intended audience effectively.

Local Research

Engage in on-the-ground research within communities affected by LWE activities to better understand their internet usage patterns. This Insight can inform policy development that balances global and local needs. What might appear harmless or statistically ‘a long tail product risk’ globally can have severe consequences in specific regions.

Reporting Flows in Local Languages

Tech companies should prioritise providing accessible reporting flows in regional languages for products with a substantial user base in emerging markets. Localised reporting options with low friction ensure that users from diverse linguistic backgrounds can easily report concerning content and activities, fostering a safer online environment in regions where users widely use these platforms. Future research on support networks, global connections, and foreign group influence in LWE, primarily online, can enhance our collective understanding of the challenge.

No comments:

Post a Comment