Maradia Tsaava and Katarina Baletić

Serbia is hoping that a new free trade agreement (FTA) signed with China will be a boon for the country’s wine industry. However, the experience of Georgia, which considers itself the cradle of winemaking, suggests that Serbian winemakers shouldn’t get their hopes up.

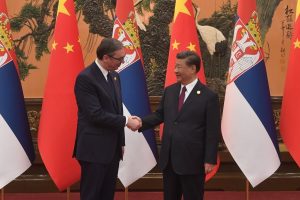

Serbia and China signed their FTA on October 17. The document was signed by Serbian Trade Minister Tomislav Momirović, who was in Beijing along with Serbian President Aleksandar Vučić for the third Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation.

The text of the agreement has been made public. Under its terms, tariff-free Chinese goods include some kinds of fresh meat, automobiles, arms, smartphones, lithium batteries, photovoltaic modules, textiles, and toys. Tariff-free Serbian goods include fruits, nuts, beef, some mechanical equipment, arms, and of course, wines. Most tariffs won’t be immediately abolished but they will be reduced year by year and then become “tariff-free” after five, 10, or 15 years.

Serbian officials are anticipating a big boost to their country’s wine exports. Praising the deal, Serbia’s agricultural minister, Jelena Tanasković, emphasized wine in an interview with Serbian state broadcaster RTS. “Today wine is subject to customs duties at a rate of 42 percent. In the next five years, it will be a zero rate,” she explained.

According to the text of the FTA, Serbian wine exporters face a base customs tariff of 14 percent, so it is unclear where the 42 percent figure comes from. Nevertheless, the new agreement does stipulate that the customs duty on the import of Serbian wine in bottles smaller than 2 liters will be abolished over the next five years at a rate of 2.8 percent each year.

At this point, it’s still unclear how these tariff reductions might play out, but the experience of Georgia, which signed an FTA with China in May 2017, provides some insight into what Serbian winemakers can expect.

It’s been five years since Georgia’s free trade agreement with China entered into force in January 2018. The agreement, which reduced custom taxes between the two countries by up to 94 percent, was highly promising for Georgia. Overnight, a market of 1.4 billion people opened up to a country of just 3.7 million.

After Georgia negotiated its agreement with China, the Georgian government put stock on exporting wine, hazelnuts, honey, mineral water, beer, jams, juices, vegetables, fruits, and fish. Wine, which is the fourth largest Georgian export, was especially important, not least because Georgia considers itself the cradle of winemaking. After the Georgian agreement was signed, local businesses hoped that China might replace Russia as the main export destination for Georgian wine.

Since 2017, exports from Georgia to China have doubled, but this growth mostly consists of ore and metals. There has been little effect on small- and medium-sized businesses that produce wine or other local products.

Ultimately, Georgia has never sold more than 10 million bottles of wine per year in China. This number is not too far from what was sold before the agreement – 9.2 million, according to Levan Tavadze, a winemaker who has been living in China for 27 years.

In Serbia, some experts are already pessimistic about the new FTA’s prospects. Even if the agreement guarantees cheaper Serbian exports, the question remains as to whether the Serbian economy is able to take advantage of this opportunity. Predrag Bjelic, a professor at the Faculty of Economics in Belgrade, is doubtful.

“What if our wine is good and in China they are delighted? Do we have the capacity for such production? What about the logistics?” Bjelic asked. “We can deliver two, three, or five cases, but China is a big market. What if they ask us for 1,000 cases?”

Serbia produces around 25-30 million liters of wine annually, which is, of course, just a drop in the ocean when it comes to the Chinese market.

According to Bjelic, all of these questions should have been answered before entering into negotiations with China. In the case of disproportionately sized economies – a large economy like China and a significantly smaller Serbia – Bjelic says the agreement should also include “nonreciprocal treatment,” meaning that concessions are included to adjust for disparity in economic strength.

On the other hand, oenologist and professor Marko Malićanin said that an agreement with China would be an excellent opportunity for Serbian wine producers. “The Chinese market is vast and diverse. What’s interesting about this market is that, unlike Russia, where you can only place cheaper wines, in China, you can sell very expensive wines,” he noted.

However, he added that the “fundamental issue with the Chinese market is that China is still not a stable market – you can do business one year, and then be uncertain about repeating it the next.”

According to Malićanin, Serbia already exports wine to China and certain wineries thrive due to the Chinese market. He added that the trade agreement with China is yet another reason to invest heavily in planting new vineyards, ensuring a domestic grape supply and boosting the export potential of wine.

In Georgia, few winemakers have been able to overcome this problem of scale. Only two winemaking companies held a place in the top 10 list of export companies in 2023: Khareba and Dugladze Winery.

“Since the agreement was signed, exports to China have doubled and China is taking a big share in Georgian exports, but this [consists of] ore mostly. The share of wine exports is almost insignificant, despite the high hopes of the Georgian government, local business and the civil society,” said Gvantsa Meladze, a member of the Supervisory Board at the Export Development Association in Georgia.

According to Meladze, several factors have led to this frustration. “China couldn’t compete with Russia. Although Chinese pay a higher price per bottle, selling here is more challenging because of the language barrier and business culture differences. Also, the Chinese market is quite complicated in terms of governmental regulations,” she said.

Levan Tavadze, who is based in Beijing, has been selling 20-30,000 bottles per year, for 11 years, under the name of Satavado. He says a lack of familiarity on both sides poses steep hurdles. “People in China are used to French wine. Georgian wine is new to them – they know nothing about it. [The] Chinese market has its own rules that a newcomer has to know: starting from how to shape and brand the bottle, ending [with] which variety to choose. Georgians mostly don’t know much about this,” Tavadze explained.

As a result, only the big companies like Khareba and Dugladze Winery, producing a few million bottles per year, have managed to find their way onto the Chinese market.

According to Tavadze, “big companies with huge productions have the capacity to contact big sales agents, but for small businesses selling 20,000 bottles per year, it’s extremely difficult. This number is absolutely nothing for the scale of China and no agent is interested.”

Georgia’s experience suggests that Serbia’s hopes for a boom in wine exports to China may be far-fetched. To date, such products make up a very small proportion of Serbia’s trade with China.

Exports from Serbia to China have grown significantly in recent years, but as is the case with the growth in China-Georgia trade, this is primarily due to the export of copper. According to official data, copper and ore exports accounted for more than 93 percent of the total value of exports to China in the first seven months of this year. The situation was similar last year – of total exports worth 1.1 billion euros, more than 980 million euros was accounted for by the export of copper and ores.

In Serbia, this copper largely comes from mining operations owned by subsidiaries of the Chinese company Zijin Group. The “tires” included in the list of Serbian goods that will be tariff-free under the new agreement are also likely to come from another large investment in Serbia: the $1 billion tire factory by Shandong Linglong in Zrenjanin.

Despite the disappointment of Georgian winemakers, Georgia’s FTA with China is arguably better than no FTA. After all, Georgian exports to China in 2022 did reach more than $694 million, an increase from around $190 million in 2017. “Expectations are always higher than the reality, but to evaluate the outcome of the agreement, it’s positive,” summed up the head of Georgia’s Export Development Association, Giorgi Gudabandze.

Giorgi Abashishvili, the founder of Business Insider, shares this opinion. “It’s hard to evaluate these five years because of the pandemic… But it’s significantly important for Georgia to diversify its trading market, especially after [the] Russia-Ukraine war.”

According to Girogi Gudabandze, the big remaining challenge for Georgia is to develop infrastructure links with China, “to cover the long distance between Georgia and China and use our unique potential to become the logistic hub connecting Europe and Asia.” In June of this year China and Georgia elevated relations to the level of a “strategic partnership.” The Chinese also expressed interest in the controversial Anaklia deep sea port project, suggesting renewed interest in Georgia’s role as a transit corridor to Europe.

The same challenge exists in Serbia. According to Bjelic, besides the problem of scale, there is also a problem of logistics. Regarding the export of Serbian wine, he asked, “Can we produce it and do we have a train where we will load and deliver it to China?”

The challenges facing Georgia and Serbia are similar, and there is reason to believe that Georgia’s experience foreshadows that of Serbia. The new FTA is likely to increase overall trade between China and Serbia, but the emphasis will be on existing trade in raw materials, leaving the expectations of Serbian winemakers unmet.

No comments:

Post a Comment