Andrew Thornebrooke

Each day, Ukrainian soldiers trudge over a morass of dried mud. They stop frequently, staying low to the ground. For much of the day, they hunker in ditches and dig small trenches while they wait for their Soviet-era mine-clearing vehicles to complete their laborious task.

They know that a Russian unit is nearby. Perhaps just behind the tree line.

Russia has amassed 100,000 troops and more than 500 battle tanks just east of here, past Bakhmut. None of the soldiers know where those Russian troops will deploy, but everyone knows that they will deploy. Maybe they already have. A day without contact is exceedingly rare.

They can only hope that the unit doesn't attack again. They have lost men already and can't afford to lose their mine-clearing capability.

If these Ukrainians are lucky, they'll advance the length of two football fields today.

The Trident

It's this way along most of the front lines, which now sprawl more than 600 miles, bisecting the nation.

Just four months into Ukraine’s counteroffensive, the fighting is a meat grinder in which gains are measured in feet and never miles. Still, Ukraine pushes on, advancing slowly and relentlessly south and east into occupied territory.

It's making three key thrusts against the Russians, like points on the trident that defines Ukraine’s coat of arms.

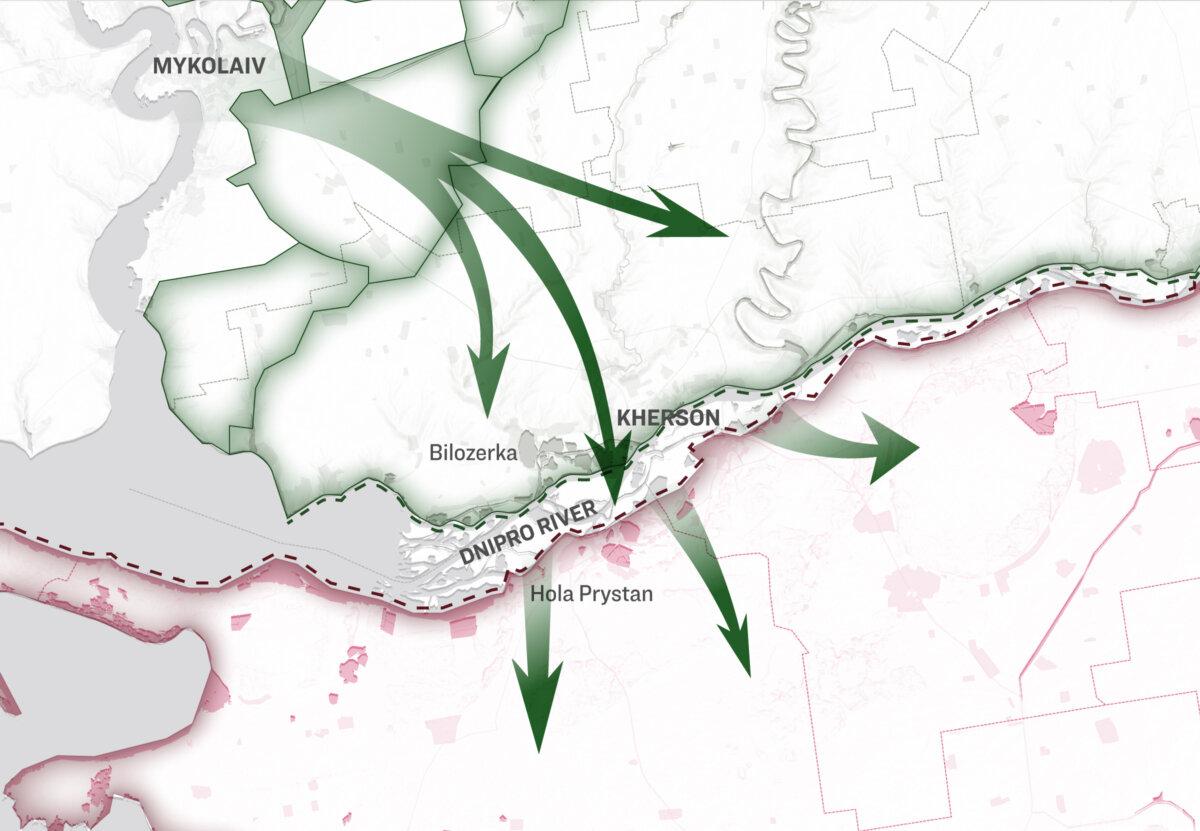

In the south, Ukrainian forces are staging amphibious assaults across the Dnipro River near Kherson. Some of their greatest gains have been made along this stretch of river and, if they can push further, they may secure a path to occupied Crimea by the end of next year.

An illustration of Ukrainian forces launching assaults across the Dnipro, towards Crimea, near Kherson.

In the east, they march around the ruin of fallen Bakhmut and work to shore up defenses against an always-growing mass of Russian reserves.

Between these two points—at the tip of the trident—is key.

It's here that Ukrainian forces pushed through Russia’s first and strongest line of fortifications and liberated the town of Robotyne in early September.

Some among Ukraine’s military leadership believe that Ukraine has now broken through the most difficult of Russia’s defense networks in southern Ukraine.

An illustration shows that if Ukrainian forces can push from Robotyne into Tokmak, they could continue to push southward towards the Sea of Azov, possibly taking either of the Russian-occupied cities Mariupol or Melitopol.

Robotyne, located in the Zaporizhzhia region, sits on the road between the frontline town of Orikhiv and the Russian-occupied rail hub of Tokmak. Its strategic placement could give Ukraine further ability to attack key Russian supply lines.

If Ukrainian forces can push from Robotyne into Tokmak—roughly 18 miles south—they could effectively split the Russian forces occupying the region north of the Sea of Azov, cutting off supplies to those located in Kherson and western Zaporizhzhia.

Moreover, it would give Ukraine a vantage from which to push southward through Zaporizhzhia province, toward the Sea of Azov, and to take either the occupied port city Mariupol, or Melitopol further west.

But 18 miles is a long way for an army moving the length of two football fields a day. Particularly with the brutal eastern European winter on the horizon.

To seize either Mariupol or Melitopol would come at great cost, no doubt, but would cut off thousands of Russian troops from their supply lines and deny Russia its only land bridge into Crimea.

Ukrainian leaders are tight-lipped about their intentions, and no one outside of command knows for sure in which direction the next push will go. But it's clear enough that they intend to claw back every inch of ground lost to Russia’s attempted conquest.

It's also clear that peace isn't imminent, nor is it currently being sought.

Victory—it's understood—will be achieved in years rather than months.

An illustration shows the liberated and Russian-occupied territory along the font line in southern and eastern Ukraine.

The Surge That FailedHow Ukraine’s much-hyped counteroffensive got to this vicious standoff is still a point of contention.

When Ukrainian military leadership announced its counteroffensive on June 4, Western advisers urged a swift retaking of key points. The Ukrainian military, eager for better arms and equipment from their richer Western partners, complied—at least, at first.

Mechanized troops roared to the task of breaking the Russian lines, only to become immediately bogged down in mud and minefields—perfect prey for Russian hunter-killer teams waiting in ambush.

By July, the advance had slowed to a snail’s pace, bringing analysts in the United States to question whether the war was winnable at all. Russian forces seized on the lull and quadrupled the size of their minefields from June to September, adding extra depth and density of mines across the front.

Ukraine’s mine-clearing vehicles—outfitted to clear about 90 yards of mines—faced minefields five times that long.

By late August, the White House was forced to clarify that it didn't believe the counteroffensive was a stalemate, but that it was open to a “negotiated peace” settlement between Ukraine and Russia.

Russian servicemen wearing Explosive Ordnance Disposal (EOD) equipment while demining a field in the Donetsk, Ukraine, on June 23, 2023.

Still, while many Western advisers were frustrated with the lack of noticeable gains on a map, Ukrainian officers were beginning to adapt to the reality of the battlefield. Ukraine, they decided, would embrace the slow, agonizing, but winnable form of warfare that has now come to dominate the front lines.

NATO is now beginning to recognize the fruits of that slow, grinding work. Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg acknowledged during a Sept. 28 visit to Kyiv that Ukraine was “gradually gaining ground."

The allies, he said, must accept the costs to come in order to prevent a greater cost that would inevitably be wrought by capitulating to Russia and thereby ushering in a new era of conquest.

“The stronger Ukraine becomes, the closer we come to ending Russia’s aggression,” Mr. Stoltenberg said.

“Russia could lay down arms and end its war today. Ukraine doesn’t have that option. Ukraine’s surrender would not mean peace. It would mean brutal Russian occupation. Peace at any price would be no peace at all.”

Embracing the Meat Grinder

By pivoting away from the advice of foreign analysts and focusing on a slower form of maneuver warfare, Ukraine has retaken more than a dozen fortified villages in just more than two months.

The strategy, fought primarily with small unit infantry assault augmented by precision fires from artillery, is fruitful but slow. Every step is hard fought.

Firefighters putting out a fire from a Russian strike in Zaporizhzhia, Ukraine, on Oct. 6, 2022.

Ukrainian forces now average an advance of between just 460 feet to 790 feet per day, according to one report (pdf) compiled by the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI), a UK-based think tank.

Brutal as it may be, that pace is allowing Ukraine to preserve much more of its manpower and equipment, whereas its previous attempts at rapid breakthrough wrought havoc on its already precious supplies.

Those early Ukrainian losses may thus point to a failure of Western advisers rather than Ukrainian officers, Nataliya Bugayova, a fellow at the Institute for the Study of War think tank, wrote in a Sept. 25 report.

“Ukraine recognized the realities of Russian defenses much faster than Western policymakers, who were expecting a rapid Ukrainian breakthrough,” Ms. Bugayova says in the report.

“The Ukrainian forces have done what successful militaries do. They have adapted and are now advancing.”

Western officials wanted a blitzkrieg but, in the most simple terms, Ukraine can't hold the territory that it gains if it goes any faster.

By delaying the culmination of the counteroffensive, Ukraine can ensure that it liberates the most territory possible and degrades a maximal amount of Russian capabilities on the way.

Still, the slow pace does grant Russian forces time to adapt as well, and they are.

Although they're losing ground, the Russian forces have solidified and are now conducting orderly withdrawals and successfully impeding Ukrainian advances even as they're in retreat.

Such rearguard actions, in addition to slowing Ukraine’s advance, also take their toll on Ukraine’s materiel.

A Ukrainian soldier throws an empty shell as his artillery unit fires towards Russian positions on the outskirts of Bakhmut, Ukraine, on Dec. 30, 2022.

Thus, to maintain its hard-won momentum against such a massive enemy, Ukraine requires outside aid. That means continued security aid from Western allies not only in the near term, but perhaps for years to come.

To that end, Ms. Bugayova says that Western advisers need to embrace Ukraine’s way of war—not only for this counteroffensive, but through the winter and the next counteroffensive as well.

“Ukrainian operations can and will likely continue even in rain and mud, even if they occur at a slower pace,” she said.

“Ukraine can win this war militarily, but it will take more than one counteroffensive operation.”

Munitions Shortages Alter StrategiesThis dependence on the United States and its European partners raises a vital question.

There's no doubt among the Ukrainian rank and file that they're in it for the long haul. Whether or not Ukraine can obtain the resources required to sustain that long haul is a separate matter, however.

Already, supply shortages have at various times critically impacted both Russian and Ukrainian operations. Leadership in Moscow and Kyiv have had to adapt to the reality that much-needed munitions are going to be in short supply for the foreseeable future.

Moscow, like Kyiv, began the war with an overwhelming reliance on artillery fire.

An artillary unit fires towards Russian positions in eastern Ukraine on Dec. 28, 2022.

According to the RUSI report, Russian forces initially adhered to projections of how many shells would be needed for various types of engagements based on strategic doctrines from World War II. Now, in the second year of the war, Moscow has adapted to the fact that it simply doesn't have the ammunition or control the logistical routes necessary to sustain such rates of fire for very long.

Here, Ukraine has held an advantage in the east. Ukrainian forces’ ability to make advances, the RUSI report says, has been largely dependent on its ability to gain superiority in artillery fires.

“Outranging the Russians, combined with having better means for detecting enemy artillery and carrying out counterbattery fires, is an essential Ukrainian advantage,” the report says.

“This advantage is limited in its duration by the serviceability of Ukrainian artillery pieces, the availability of replacement barrels, and the continued supply of 155-mm ammunition.”

That’s a problem, as numerous NATO nations are now facing 155 mm munitions shortages themselves. Foremost among them is the United States.

Fears of uncomfortably low artillery stores have grown since August 2022.

A worker checks the production of 155mm artillery shells at the Scranton Army Ammunition Plant in Scranton, Penn., on April 12, 2023. The United States, among numerous NATO nations, is now facing 155mm ammunitions shortages as the country continues to supply them to Ukraine.

Since then, Army Secretary Christine Wormuth has said that U.S. munitions production capacity is pushed to the “absolute edge.” Then-Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman Mark Milley had said that the nation “has a long ways to go” to replenish its sorely depleted stockpiles.

The United States currently plans to raise its production of munitions by 500 percent by 2027, but that number would still fail to meet the current levels required by half.

The Pentagon has taken steps to stop the hemorrhaging of its critical munitions stocks by purchasing ammunition for Ukraine from other countries rather than stripping its own stores.

How long the current balance can be kept is an open question, however. Allied stockpiles aren't infinite either, and some partners are already thinking about their own security concerns.

South Korea, for example, has refused requests to sell munitions to the United States, citing concern about North Korean aggression.

Now, the United States is going so far as to pull equipment from units stationed in Israel and South Korea to adequately supply Ukraine without emptying its stockpiles.

It’s clear that should Ukraine hope to maintain its advantage, it will need to find something other than artillery with which to do it.

Planes, Tanks, and Automobiles

For its part, Ukraine is seeking to augment its counteroffensive with new capabilities, enhancing the posture of its infantry with armor, long-range drones, and advanced fighter jets.

The first deliveries of the U.S.-made Abrams battle tanks arrived in Ukraine in late September. Included with them are 120 mm depleted uranium rounds. The munitions, made from an immensely dense metal, will give Ukraine a long-sought-after capability to punch through Russian tanks.

(Left) A Ukrainian soldier prepares to launch an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) in Donetsk, Ukraine, on June 27, 2023. (Right) Ukrainian soldiers monitor units as they move towards Donetsk, Ukraine, on Sept. 5, 2023.

Similarly, Dutch and Danish leadership agreed in August to give F-16 fighter jets to Ukraine. Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy said that the technology would help Ukraine to expand its counteroffensive and bring about a new method of warfare along the front.

“[The] F-16 will certainly give new energy, confidence, and motivation to fighters and civilians,” Mr. Zelenskyy said in a message to the Ukrainian armed forces. “I’m sure it will deliver new results for Ukraine and the entire [European region].”

Ukraine has long sought the fighter craft but was stymied by the United States, which feared that providing the planes would increase the risk of nuclear conflict with Russia.

Much about the deal remains unclear, including precisely how many warplanes Ukraine will receive and how much time will pass before its pilots are flying the F-16 through Ukrainian and, possibly, Russian skies.

Likewise, it remains unclear how willing Ukraine is to stick to its promise to not use the aircraft to take the fight to Russian territory, possibly escalating a conflict already tense with threats of nuclear annihilation.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky (L) and Danish Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen sit in a F-16 fighter jet at the Skrydstrup Airbase, Denmark, on Aug. 20, 2023. Dutch and Danish leadership have agreed to give Ukraine F-16 fighter jets, which Zelenskyy said would help Ukraine expand its counteroffensive.

US Support a Wild CardAll of this support, however, highlights one potentially fatal weakness in Ukraine’s counteroffensive strategy: its reliance on the United States.

As of Sept. 26, the United States had approved more than $113 billion in spending packages in response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The vast majority of those funds have been spent through the Department of Defense and the U.S. Agency for International Development.

It isn’t clear how much more the United States can continue to spend. More importantly, it isn’t clear if the United States has the will to spend what it does have.

To that end, three Republican presidential hopefuls have made divesting from the war a priority on the campaign trail. Former President Donald Trump, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, and businessman Vivek Ramaswamy have all vowed to cut support from Ukraine and to seek peace with Putin.

Moscow may not need to wait out Ukraine in that case. It may just need to wait out the Biden administration.

That could mean big trouble for Ukraine, whose recapture of occupied territory will require funding mechanisms years in advance.

(Left) Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis speaks at his campaign event in Clive, Iowa, on May 30, 2023. (Right) Republican presidential candidate Vivek Ramaswamy speaks at the Iowa Faith & Freedom Coalition in Clive, Iowa, on April 22, 2023.

As the RUSI report finds, the decisions that will mold Ukraine’s successes in 2024 are already being made. Those to shape 2025 and beyond will arrive shortly.

“It is now clear that the conflict will protract,” the report says. “Failure to make timely adjustment[s] to support will come at a heavy price in 2024.”

Bloody Winters to Come

For its part, Ukrainian military leadership isn't going to wait for a chance to launch another counteroffensive. It appears intent on making the most of the support it does have and fighting even as bitter winter sets in.

“Combat actions will continue in one way or another,” Kyiv's intelligence chief, Kyrylo Budanov, said at a conference in early September.

“In the cold, wet, and mud, it is more difficult to fight. [But] fighting will continue. The counteroffensive will continue.”

It's likely that Russia hopes to stall Ukraine during the colder months by increasing attacks on food and energy infrastructure as it did last year.

To that end, keeping pressure on Russia, limiting its ability to hit infrastructure and build reserves, will be a key objective for Ukraine throughout the season.

“Ukraine’s current offensive operations are likely to continue into the autumn, but the question should be asked whether actions can be taken now to maintain the pressure through the winter,” the RUSI report says.

Even should Ukraine fight, and fight well through the winter, there remains the problem of the sheer size of territory to be liberated.

Ukrainian soldiers walk through a charred forest at the frontline near Donetsk, Ukraine, on Sept. 16, 2023.

To date, Ukraine has liberated about 10,600 square miles of territory in the occupied east and south, according to DeepState UA, a recognized open-source intelligence group trusted by the Ukrainian military.

There remains, however, more than 62,000 square miles of Russian-occupied territory in eastern and southern Ukraine. Importantly, that number doesn't include the illegally annexed territories in Crimea, Donetsk, and Luhansk, which now operate under Russian puppet governments.

If these territories are included as Russian-occupied Ukraine—which U.S. officials have suggested they should be—the total area remaining to be liberated is roughly 106,000 square miles.

Ukraine, therefore, has liberated only approximately one-tenth of the occupied territory in the east and south.

“Irrespective of the progress made during Ukraine’s counteroffensive,” the RUSI report says, “subsequent offensives will be necessary to achieve the liberation of Ukrainian territory.”

If the Ukrainian advance is to be maintained, then, the country will need to fight and receive massive amounts of money and materiel from allies for years to come.

No comments:

Post a Comment