Billy Perrigo

Set back from a dusty highway in South India, three newly completed factory buildings rise up behind a black spiked iron fence. In their shadow, several yellow construction vehicles sit beside mounds of upturned soil and the skeleton of a half-built warehouse. On a May afternoon this year, a group of women in blue and pink uniforms hurried from one building to another over the din of traffic and construction.

Set back from a dusty highway in South India, three newly completed factory buildings rise up behind a black spiked iron fence. In their shadow, several yellow construction vehicles sit beside mounds of upturned soil and the skeleton of a half-built warehouse. On a May afternoon this year, a group of women in blue and pink uniforms hurried from one building to another over the din of traffic and construction.This factory complex in Sriperumbudur, an industrial town in Tamil Nadu state, is one of Apple’s most important iPhone assembly hubs outside of China. It is operated by Foxconn, a Taiwan-based electronics manufacturing company. Three times per day, the gates to this factory open to swallow buses ferrying thousands of workers—around three-quarters of them women. These workers spend eight hours per day, six days per week, on a humming assembly line, soldering components, turning screws, or operating machinery. The factory is one of the biggest iPhone plants in India, with some 17,000 employees who churn out 6 million iPhones every year. And it’s fast expanding.

Most of the 232 million iPhones Apple sold in 2022 came from factories in China, with many of them originating from a single massive Foxconn facility in Zhengzhou. But shifting geopolitical tides have recently forced Apple to re-evaluate its exposure to China. First came the pandemic, when Beijing’s harsh lockdowns badly disrupted global supply chains. Now U.S. intelligence assessments, made public this year, say that Chinese President Xi Jinping has instructed his military to be prepared to invade Taiwan by 2027, and President Biden has said the U.S. would defend Taiwan in that scenario. A hot war with China could have disastrous consequences, not only for the world, but also for Apple’s ability to manufacture many of the products behind its $2.7 trillion business.

And so the company is hedging its bets on India, a country shielded from China behind the world’s highest mountain range, and home to a young population of 1.4 billion people. In September 2022, Apple announced the iPhone 14 would be assembled in India for the first time. (Until then, the Sriperumbudur factory handled only older models.) In April of this year, Apple CEO Tim Cook flew to India, where he met with Prime Minister Narendra Modi, pledged to invest ever more deeply in the country, and personally opened two Apple Stores. Now, workers at the Sriperumbudur factory are reportedly assembling the new iPhone 15, which went on sale in September.

Powering Apple’s pivot to India is Foxconn. By 2024, Foxconn hopes to nearly quadruple its production at this South Indian factory to 20 million iPhones per year, and reportedly plans to hire tens of thousands more workers to make that possible. Satellite images provided to TIME by Planet Labs show rapid expansion at the complex, with three new factory buildings constructed over the past two years and newly broken ground on space large enough to accommodate at least three more. Apple could manufacture 25% of all iPhones in India by 2025, up from just 5% in 2022, according to a JPMorgan analysis.

Satellite imagery courtesy of Planet Labs

This shift toward India has winners and losers. Foxconn has a history of low pay, harsh working conditions, and exacting targets in its Chinese factories. And as Foxconn rushed into India to meet Apple’s demand, it created comparable conditions there. In 2021, 159 factory workers were hospitalized with food poisoning, as a result of eating unhygienic food at a subcontractor-provided hostel. That incident set off a wave of protests that, for several days, drew media attention to the squalid living conditions faced by iPhone assembly workers. The hospitalizations were followed by a government inspection into the factory—which has not previously been reported—that described numerous safety risks and workers’-rights violations. That government inspection, carried out in December 2021, prompted Foxconn to spend $1.6 million on improving health and safety in the factory with oversight from Apple and the state government of Tamil Nadu, Foxconn said in a statement to TIME.

This story is based on an unreleased government document reviewed by TIME, as well as interviews this spring with four current workers and eight community organizers in and around Foxconn’s Sriperumbudur factory. All workers spoke on condition of anonymity, out of fear that speaking to the media would invite retaliation. “What we do in this factory is not what we studied for,” one female worker told TIME. “But it has become a matter of survival for our families.”

Apple declined TIME’s request for a reporter to be given a tour of the Sriperumbudur factory for this story, and refused two requests to make a senior executive available for an interview. Foxconn did not respond to similar requests. In a statement, an Apple spokesperson said that the issues at the Sriperumbudur factory were addressed after the food-poisoning incident, and added that regular Apple audits have found that the conditions in the factory are continually improving. Foxconn said the health and safety of its employees is “a top priority.”

An inspector calls

At 9 a.m. on Dec. 17, 2021, two days after the food-poisoning incident, a health and safety inspector from the Tamil Nadu state government turned up at the gates of the iPhone factory in Sriperumbudur.

The inspection found that six workers whose job was to manually solder iPhone parts together “were not provided with protective equipment” including safety goggles, chemical-resistant gloves, or respirators, according to a letter sent by the government inspector to Foxconn, a copy of which was reviewed by TIME. In the areas of the factory where soldering was carried out, the inspection found, the ventilation system was not sufficient to prevent “the escape and spread of toxic fumes into the working environment.” That soldering process, the letter said, was “highly hazardous to the health of workers.”

In another part of the factory, the inspector found that workers “were not provided with suitable goggles to protect their eyes from the excessive light and infrared radiation.” He identified 77 pieces of automated machinery that were missing crucial “interlock” mechanisms on their doors to prevent operation under dangerous conditions, and 262 instances of missing guards on pressing machinery. The lack of these protective mechanisms, the letter said, posed a risk of bodily injury. And six large industrial ovens used to attach tiny electrical components to iPhone circuit boards, the letter said, had not been “tested by a competent person” before factory workers were expected to use them.

The inspection also found several apparent employment-law violations, according to the letter. At least 11 workers in the factory, it said, had been required to work excessively high hours for the past three months. At least 17 workers had been required to work on Sundays—usually their only weekly day off—without being given a replacement day of leave within three days. “All latrines and urinals in the factory were not maintained in clean and sanitary conditions at all times,” the letter said, and debris was present on the ground floor of the factory that presented a safety risk. The factory manager had failed to keep a register of workers in the factory or a register of their wages, the inspector claimed. And more than 4,500 of the 6,126 workers in the factory at the time of inspection were allegedly employed not by Foxconn, but by 11 different subcontractors that were not legally registered with the Tamil Nadu directorate of industrial safety and health.

The letter suggests that the inspector found multiple violations of state law. The same findings would also likely constitute violations of Apple’s 127-page “supplier code of conduct” which—on paper—guarantees the people who build iPhones the right to dignified work in a safe environment. This code says that Apple suppliers must provide “safe working conditions” including by providing personal protective equipment, ensuring adequate ventilation, and maintaining proper safety mechanisms on machinery. Any overtime must be voluntary, the document says. Workers should receive at least one day off per seven days, it adds, and have access to clean toilet facilities. Apple does not prevent its contractors from using third-party labor agencies to supply workers, but says these agencies must be legally registered. “Any violations of this Code may jeopardize a supplier’s business relationship with Apple up to and including termination,” Apple’s supplier code of conduct states.

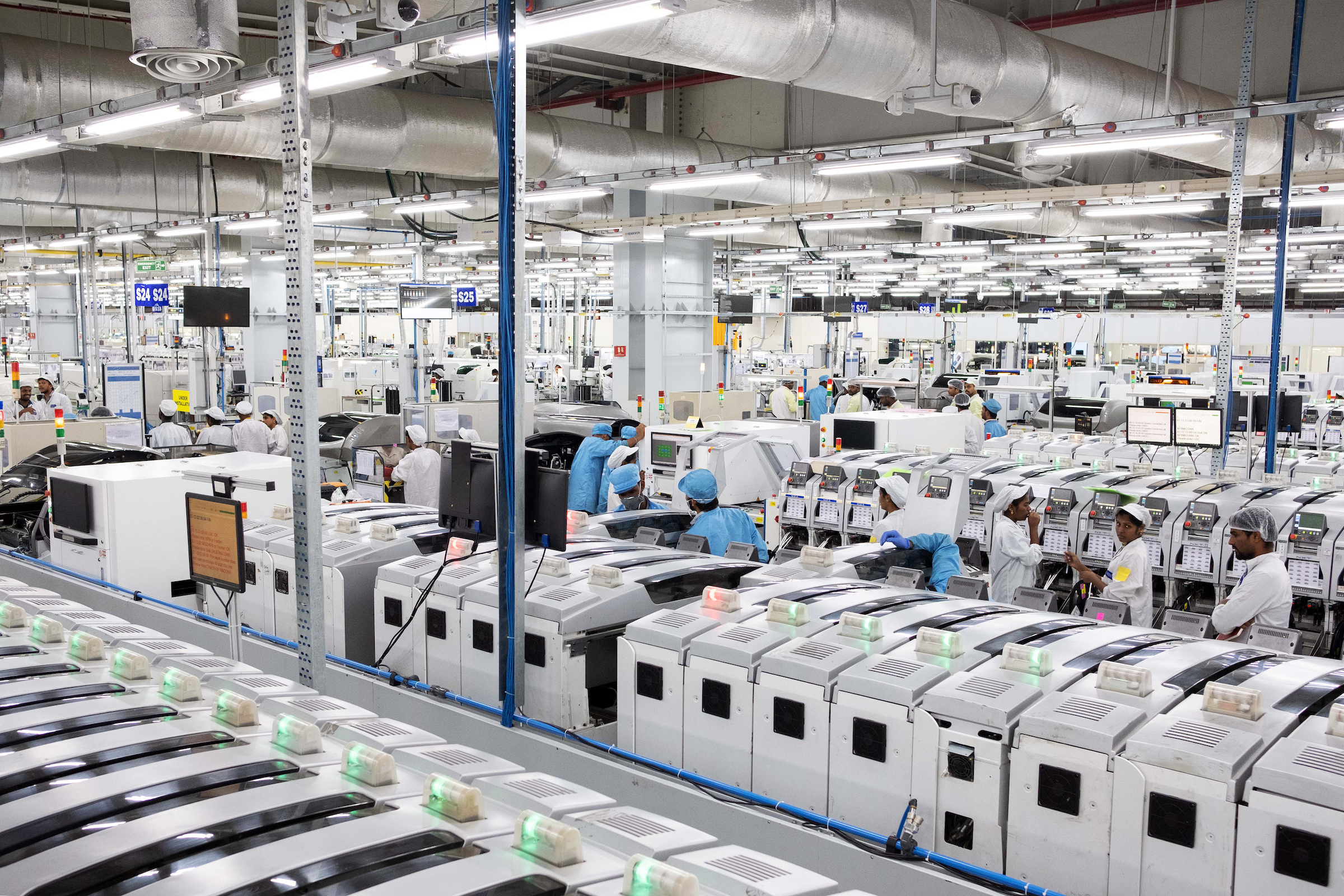

Employees work on an assembly line in the mobile phone plant of Rising Stars Mobile India Pvt., a unit of Foxconn Technology Co., in Sriperumbudur, Tamil Nadu, India, on Friday, July 12, 2019.

The Tamil Nadu inspector’s letter to Foxconn warned that “suitable action” would be taken against it within seven days, unless the company could explain why it “should not be prosecuted for the irregularities found” during the inspection. TIME was not able to confirm what measures, if any, the Tamil Nadu state government took in the aftermath of the letter. The Tamil Nadu directorate of industrial safety and health, which carried out the inspection, did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

The day after the inspection, Foxconn closed the factory. Shortly after, Apple sent in a team of independent auditors. But in public statements at the time, neither company mentioned that a government inspector had described a litany of failings inside the massive factory complex. Instead, both Apple and Foxconn issued statements saying that they were concerned by the hygiene failures at off-site hostels, and that they would quickly work to address the conditions there. The statements gave the impression that the main risk to workers’ health and safety came from hostels run by subcontractors—not from Foxconn’s very own factory floor. The factory remained closed for nearly a month, and a phased reopening began on Jan. 12, 2022.

In their statements to TIME for this story, Apple and Foxconn acknowledged that an inspection took place at the factory but did not comment on specific findings. “We took measures and addressed every issue the government raised from its inspection,” a Foxconn spokesperson said in a statement to TIME, without specifying what those issues were. “The health and safety of our employees is a top priority for Foxconn.”

An Apple spokesperson also declined to comment on specific findings. “The issues at Foxconn Sriperumbudur were investigated and addressed a year and a half ago and we placed the facility on probation,” the spokesperson said in a statement to TIME in May. “During this period Foxconn invested in significant improvements and through quarterly, and at times weekly audits, Apple and independent auditors have tracked meaningful upgrades to the facility with frequent visits and employee interviews.” Apple-run surveys found employee satisfaction at the factory to have increased by 27% between August and December 2022, the spokesperson said.

Life inside the Foxconn factory

Foxconn implemented some positive changes in the months after the inspection, protests, and factory closure, according to three workers who spoke with TIME. Foxconn removed a rule that workers had to live in subcontractor-provided hostels, and increased workers’ salaries by 5,000 rupees ($60) per month to cover the costs associated with renting accommodations independently. Both the food in the factory’s canteen and the working conditions on the factory floor have improved since the protests, the workers said, while acknowledging that significant problems remain.

Since the factory shut down and reopened, four current workers told TIME in May, it is generally a safer place to work. The same workers, however, complained of high production targets, as well as a system of subcontracting that in effect creates a two-tier workplace where a comparatively small number of Foxconn employees enjoy greater benefits and job security than a legion of temporary workers, hired by third-party Indian subcontractors, who also work inside the factory. (Three of the current workers TIME spoke with were employed via subcontractors; one was a Foxconn employee.)

While the workers TIME spoke to agreed that conditions in the factory had improved since the 2021 protests and subsequent inspection, they also said that many problems persist. One problem three workers mentioned was their wages: ranging from 82 to 101 rupees per hour for slightly different roles inside the factory, equivalent to between $0.99 and $1.22 per hour. While such wages are more than double Tamil Nadu’s minimum wage for electronics workers, and still better than the perils of unemployment or work in India’s vast informal sector, they give workers little opportunity to move up the economic ladder, especially since many of them have children and elderly parents to support. “In the Indian context, this is not a terrible wage. It’s not a fair wage, but it doesn’t shock me,” says Ramapriya Gopalakrishnan, a labor lawyer based in the nearby city of Chennai. To rent a room in the towns surrounding the factory would cost around one-third of a worker’s monthly paycheck, she says. “To support two kids in school on top of that, and support a mother and father, it would be very difficult.”

Before the beginning of each daily shift at Foxconn’s Sriperumbudur factory, Foxconn managers announce production targets. Some days, according to two assembly-line workers, the targets can require each worker to work on as many as 520 iPhones per hour—or one every seven seconds. At those rates, each worker on the production line could handle some $4 million worth of iPhones every day.

Every worker on this assembly line has a designated task. Some are experts at attaching a specific component to the iPhone’s motherboard. Others have learned the precise finger movements necessary to tighten an individual screw. At regular stages some workers perform quality checks, to make sure nothing has gone wrong as each phone barrels from one point along the assembly line to the next.

Meena, a contract worker on the factory floor, says she spends eight hours per day, six days per week, hunched over her station, fingers constantly in movement. “Some days, I don’t even get time to go to the restroom because I have to meet my production targets,” she says. “If the supervisor notices that products are piling up on the conveyor belt at my stage, he will reprimand me.” Her delicate task—the specifics of which, like her real name, TIME is not revealing in order to protect her identity—causes pain in her fingers, wrists, elbows, shoulders, neck, and back, Meena says. If she changes her position to alleviate the pain—for example by crossing her legs—a supervisor will often hassle her to sit properly, she says. Foxconn allows workers facing health issues to take short rests and provides them with over-the-counter pain medication, Meena says. But after her rest break, Meena says she is still expected to continue at a demanding pace for the rest of the day.

Meena is not employed directly by Foxconn. Instead, like many of her colleagues in the factory, she is employed by a third-party contractor. This system is not unique to Foxconn, according to Gopalakrishnan, the labor lawyer. It’s common in the Indian manufacturing sector, she says, because it helps factory owners maintain a flexible workforce to which they bear few legal obligations.

“Unlike fixed-term employees, these so-called contract laborers do not know even whether they can earn their livelihood beyond tomorrow—that is the degree of uncertainty we are talking about,” says Gopalakrishnan. “This whole contract labor system is designed to lower labor costs and evade responsibility for compliance with labor laws.”

At the Sriperumbudur factory, contract workers do not receive sick leave or vacation days, and are not given copies of their contracts, according to three who spoke with TIME. Foxconn earlier this year instituted a new policy there, the workers said, whereby if contract workers take leave on a consecutive Monday and Saturday, their monthly salary will be docked by 1,500 rupees ($18), the equivalent of several days’ pay. And if workers take three days of consecutive leave, their salary will be docked 5,000 rupees ($60), the workers said.

This appears to describe more violations of Apple’s supplier code of conduct. Apple says in the document that it holds its suppliers to the “highest standard” of labor. It specifically says that they must not use wage deductions as a form of discipline, must not prevent workers from taking bathroom breaks, and must take steps to mitigate “ergonomic hazards” including painful postures and repetitive movements.

In statements to TIME, neither Foxconn nor Apple commented on the allegations of wage deductions, poorer conditions for contract laborers, ergonomic hazards, or high production targets. “We work with relevant local agencies to ensure that all recruitment efforts follow Foxconn’s recruitment standards and guidelines, as well as local labor regulations,” a Foxconn spokesperson said. “Foxconn communicates and cooperates with stakeholders, wherever we are, to continuously create an operating environment that is healthy and competitive, while protecting the rights and interest of our employees.”

“We have the highest standards in the industry for our suppliers and regularly assess their compliance to our code of conduct,” an Apple spokesperson said. “With multiple feedback channels, including employee surveys and anonymous reporting, we are constantly looking for ways to raise the bar even further.”

An expanding system

Back at the perimeter of the Foxconn factory complex, past the mounds of dirt and the skeletal frame of the half-constructed warehouse, beyond a security hut manned by guards in white shirts, are two rows of what appear to be worker housing buildings. Both rows are four stories high and 100 meters long, and lined with concrete balconies.

These buildings may be a taste of what is to come. With Apple keen to ramp up iPhone production in India, Foxconn is reportedly planning to build huge hostels for as many as 60,000 workers near its Sriperumbudur factory. Construction is currently under way on a large plot of land inside the Foxconn complex. As a result, workers at the factory are concerned that Foxconn may again require its employees to live in company-run hostels, and could revoke the 5,000-rupee ($60) housing allowance that it currently pays its workers to cover the cost of their outside accommodation, according to three workers who spoke with TIME. (Foxconn declined to comment on its plans.)

Meanwhile, the most expensive iPhone 14 retails for $999. The most expensive iPhone 15 retails at $1,099. While Apple does not publicly disclose the difference between an iPhone’s final sale price and how much it costs to produce, the company’s most recent financial results say that for every dollar of income from product sales, the company makes around 35¢ as profit.

The four workers at the Sriperumbudur factory who spoke to TIME said that while it’s unlikely they would easily find higher wages elsewhere, they still feel they deserve better. It would take the lowest-paid among them around six months to save enough to buy a single iPhone 15—and that’s if the worker never paid for rent, food, or to support her family. “When I compare my salary to the cost of an iPhone, obviously they can pay me better,” one young woman says.

No comments:

Post a Comment