David p. Goldman

Free trade has always been the favored policy of established economic powers, and protection has been the weapon of choice of the challengers. Exporting cheap goods to undercut nascent rivals has long been a mainstay in the imperial playbook. America’s controls on technology exports to China are a historical anomaly and may produce the opposite of the intended effect.

As Michael Lind observes in his economic history of the United States, Britain responded to the surge in American manufactures during the War of 1812 by dumping goods below cost in the American market. Lind cites Henry Brougham, then a member of Parliament and later Lord Chancellor, explaining why it paid Britain to sell to Americans at a loss: “It was well worthwhile to incur a glut upon the first exportation, in order, by the glut, to stifle, in the cradle, those rising manufactures in the United States, which the war had forced into existence, contrary to the natural course of things.”

America responded in 1816 with a 25% tariff on textiles, with the support of Southern states who thought it “essential that America protect what limited industry had been established” in case of a new war. By contrast, the South, an importer of British goods rather than a competitive producer, bitterly opposed the 1828 “tariff of abominations,” designed to protect the manufacturing industry from British dumping, because the war threat had long passed.

For similar reasons, China discouraged Google services starting in 2010, protecting fledging competitors like Baudi, China’s leading search engine. Whether Google initiated its departure from the Chinese market in frustration over government censorships and hacking attacks, or whether China effectively pushed Google out, remains in dispute. Then Google CEO Eric Schmidt fulminated, “You cannot build a modern knowledge society with that kind of censorship.” Matt Sheehan reported in MIT Technology Review:

But instead of languishing under censorship, the Chinese internet sector boomed. Between 2010 and 2015, there was an explosion of new products and companies. Xiaomi, a hardware maker now worth over $40 billion, was founded in April 2010. A month earlier, Meituan, a Groupon clone that turned into a juggernaut of online-to-offline services, was born; it went public in September 2018 and is now worth about $35 billion. Didi, the ride-hailing company that drove Uber out of China and is now challenging it in international markets, was founded in 2012. Chinese engineers and entrepreneurs returning from Silicon Valley, including many former Googlers, were crucial to this dynamism, bringing world-class technical and entrepreneurial chops to markets insulated from their former employers in the US. Older companies like Baidu and Alibaba also grew quickly during these years.

Protectionism worked for China’s Internet companies, which leapfrogged their American counterparts. Online sales comprised 27% of total retail sales in China in 2022, compared to 15% in the United States. Mobile payments in China reached $US 70 trillion with a total of 158 billion transactions, compared to $8 trillion in the United States.

Consider this contrafactual scenario: In 2020, China imported $378 billion in semiconductors, or 84% of its total consumption of the critical building blocks of the digital economy. The Chinese government tried to foster its domestic industry with subsidies, but the United States—taking a leaf from Britain’s nineteenth-century playbook—united with Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea to flood China with cheap chips, semiconductor equipment, and design tools. China’s inefficient state-owned foundry, Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corp (SMIC), couldn’t compete, much less the local startups in chip manufacturing equipment. China responded, in our fictional scenario, by imposing tariffs and some outright prohibitions on imports, in emulation of its earlier protection of the Internet sector. Washington lodged complaints with the World Trade Organization and other international bodies, denouncing China’s contempt for the rules-based international order. Within two years, though, China began to market smartphones and server processors with home-produced chips.

Of course, it didn’t happen that way. Instead, Washington, DC, in October 2022, banned the export of high-end computer chips (with a transistor gate width of 7 nanometers or less) as well as the tools and software needed to make them. Because advanced chips are made with a substantial proportion of US intellectual property, the US claimed extraterritorial rights to ban exports of these chips from Taiwan and South Korea, the only countries that can make them. It persuaded the Netherlands not to sell the Extreme Ultraviolet lithography machines required to etch impossibly small transistors on a silicon wafer, and cajoled Japan to stop selling other sophisticated equipment. US nationals were forbidden to work for Chinese chip companies and equipment firms were banned from servicing existing contracts.

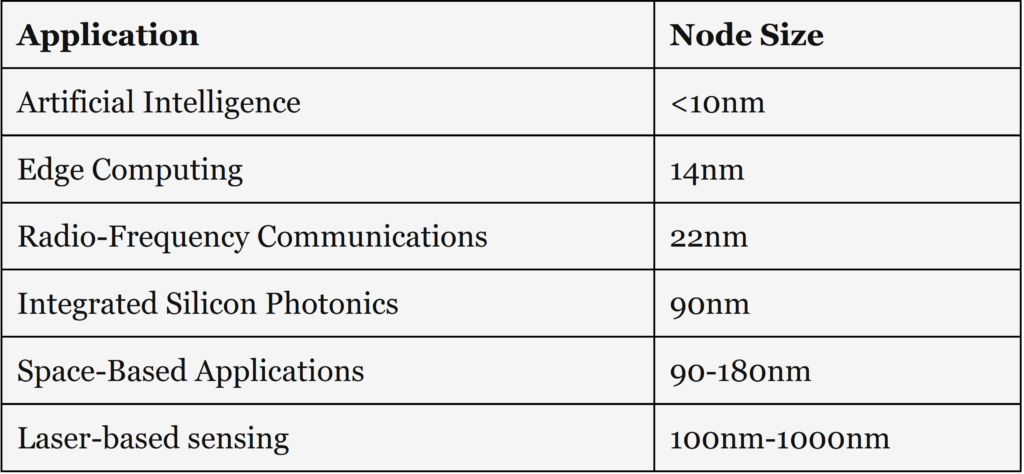

It isn’t clear what the Biden Administration was thinking. The official rationale for the chip control was to stop the Chinese military from gaining an advantage. According to a 2022 RAND Corporation study, virtually all military applications employ older chips (see chart below). The older processes are easier to harden, and most military software has been tested for years on existing hardware rather than rewritten for newer chips. Artificial Intelligence applications use faster chips, but it isn’t clear what these are. The 2,000 surface-to-ship missiles that China has pointed at our Pacific Fleet and the satellite sensors that guide them run on mature nodes.

If the objective was to hamstring China’s economy, it has failed. The chip ban undoubtedly imposed severe costs on China, which is attempting to reinvent large parts of the semiconductor supply chain at high cost. But China can recompense itself for those costs by turning excess supply into a vehicle to dominate semiconductor markets globally in the not-too-distant future.

In March 2020, the Trump Administration banned sales of high-end chips to Huawei, crushing its handset business. Without the newer, faster chips, Huawei could not make 5G smartphones, eliminating what had been the world’s biggest handset maker from the high end of the market.

Western media announced—prematurely—the death of China’s semiconductor industry. “This is what annihilation looks like: China’s semiconductor manufacturing industry was reduced to zero overnight,” wrote the Independent, in an article headlined, “US sanctions on Chinese semiconductors ‘decapitate’ industry, experts say.”

Yet in September 2023, China’s leading telecom equipment maker Huawei announced its Mate60 smartphone with 5G capability. The Canadian research firm TechInsights disassembled a copy and found a 7-nanometer chip inside manufactured by China’s SMIC. It was common knowledge that older chipmaking equipment could make a 7-nanometer chip through a laborious, iterative process, but American experts assumed that the engineering difficulties and high cost of such an exercise ruled out a commercial application. But the engineering difficulties of this exercise were formidable; in 2020, America’s largest chip fabricator, Intel, abandoned plans to manufacture a 7-nanometer chip.

We have no idea of the cost of Huawei’s 7-nanometer chip, nor how many it plans to produce, nor whether a Chinese government subsidy is involved. Chinese analysts are talking about a sales volume for the Mate60 of 6 million units, so it appears that the chip can be made in large numbers. More important is that the same chip powers Huawei’s Ascend chipset, used for its high-end Artificial Intelligence processor. The Ascend processor 910 AI processor, launched on August 29, reportedly offers performance comparable to Nvidia’s A100 chip, the instrument of choice for generative Artificial Intelligence applications. Under the American restrictions, Nvidia offers a somewhat slower version of the A100 to Chinese purchasers, namely the A800. Chinese tech companies Alibaba, Baidu, ByteDance, and Tencent have ordered $5 billion worth of Nvidia chips for delivery in 2023 and 2024, including 100,000 units of the A800.

It’s no longer accurate to think of China as a cheap labor manufacturer that takes jobs away from high-wage venues.

China’s application of Artificial Intelligence focuses on industrial rather than consumer applications. Huawei claims to have built fully automated factories where robots communicate via 5G networks and AI algorithms direct production, as well as “intelligent mines,” warehouses, and ports. In August, I toured one of Huawei’s factories near its sprawling Shenzhen headquarters, where fewer than a hundred workers produce 1,800 5G base stations per day. That’s a fifth of the world’s total installed 5G capacity at a single installation. I also visited the Tianjin Port, one of the world’s ten largest, where autonomous cranes communicate via 5G empty large container ships in less than an hour using an AI optimization algorithm. At our Long Beach, California port, the same work takes a day or two. Except for a couple of repairmen working on one of the autonomous trucks that move containers away from the autonomous cranes, there were no workers on the longshore and no operators in any of the equipment at the Tianjin Port. A handful of port employees monitor the machines from a distant tower.

AI applications are evident in the success of China’s Electric Vehicle industry, now the world’s largest as well as the world’s largest exporter. Robert Atkinson of the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation reports, “On a wage-adjusted basis, Southeast Asian nations lead the world in robot adoption. China leads the world with an astounding 8 times more robots adopted than expected, up from 1.6 times more in 2017. Korea has 4.8 times more robots than expected. Taiwan has 3.2 times more and Singapore 2.8 times more. The United States has just 70 percent of expected robots.”

It’s no longer accurate to think of China as a cheap labor manufacturer that takes jobs away from high-wage venues. Important parts of Chinese industry, notably autos, are more automated than their Western counterparts. Huawei claims that it has 10,000 contracts to install standalone 5G networks for business automation, including 6,000 factories. The Chinese government is using all of its power of persuasion as well as its checkbook to encourage businesses to get on board the so-called Fourth Industrial Revolution (the application of AI to manufacturing and logistics).

China can make the chips that train AI models on large datasets, a field dominated by America’s Nvidia. The company’s CFO last month warned, “Over the long-term, restrictions prohibiting the sale of our data center GPUs to China if implemented, will result in a permanent loss of an opportunity for the US industry to compete and lead in one of the world’s largest markets.” Qualcomm, which will sell over 40 million chipsets to Huawei in 2023, stands to lose over $10 billion in sales in 2024, according to some analysts.

For the time being, China’s production capacity for high-end chips will barely suffice to meet a portion of its domestic needs. SMIC’s engineering hat-trick with 7-nanometer chips still leaves it two generations behind Taiwan and South Korean fabricators. But that may not be the greatest risk to the Western chip industry. China may dominate the production of older (“legacy”) chips. American controls have forced China to duplicate capacity for semiconductors that it cannot buy (or fears it may not be able to buy) from the West. Global overcapacity could lead to a devastating price war that China is better situated to win.

“Legacy chips are at least as critical as advanced chips both in terms of economic importance and national security. Some 95% of the chips used in the automotive industry are legacy chips. Several other critical industries—medical devices, consumer electronics, infrastructure, industrial automation, and defense—also rely heavily on legacy chips. Russian military equipment found in Ukraine famously had legacy chips yanked from refrigerators and dishwashers,” wrote Rakesh Kumar in Fortune Magazine.

The Biden Administration’s CHIPS offers subsidies to Samsung and TSMC to build fabrication plants for advanced chips, with qualified success; TSMC’s Arizona plant is two years behind schedule, and the company has said that the chips it produces stateside will cost 30% more than the ones it produces at home.

A prominent Chinese commentator, the “Observer’s” Chen Feng, earlier this year compared China’s chip war with the United States to Mao Zedong’s revolutionary war in the 1940s. “Mid-to-low-end chips are still profitable,” Chen wrote in February, but China will not be satisfied with producing low-end chips. Instead, it will use mid-to-low-end chips as a springboard to move up to high-end chips. This is a sustainable development. China’s steel industry, which dominates the world, developed in this way. Whether we are speaking of China’s Revolutionary War or the world economy, China’s most successful strategy was encircling the cities from the countryside.

“By the same token,” Chen wrote, “the United States is focusing on high-end chips, and adopting the strategy of Menglianggu,” referring to the decisive 1947 battle where Mao’s Red Army annihilated the Nationalist Army’s mountain redoubt in Shandong Province. “But that is all the United States can do. The investment would be too costly and the payback cycle too long to rebuild the chip industry in the United States, so its only option is to start with high-end chips. It can only go to Menglianggu.”

There is a great deal we do not yet know about China’s progress in working around Washington’s technology curbs. What is clear is that China has adapted much faster than the Biden Administration expected, and that the consequences of US policy may be much harder to manage than we imagined.

No comments:

Post a Comment