Eduardo Jaramillo

Chinese companies that have received strategic investments from Huawei and Chinese government funds in recent years played a key role in Huawei’s new Mate 60 Pro smartphone, validating Beijing’s efforts to turbocharge its microchip industry in the face of American-led sanctions, according to industry analysts and Chinese corporate records examined by The China Project.

Most notably, China’s heavily subsidized flagship chipmaker, the Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation (SMIC), successfully manufactured the Mate 60’s processor, the Kirin 9000s. Upon investigation by research firm TechInsights, other components in the Mate 60 also were found to have been sourced from Chinese companies, whereas in previous Huawei models the components were supplied by American firms such as Qorvo and Skyworks Solutions.

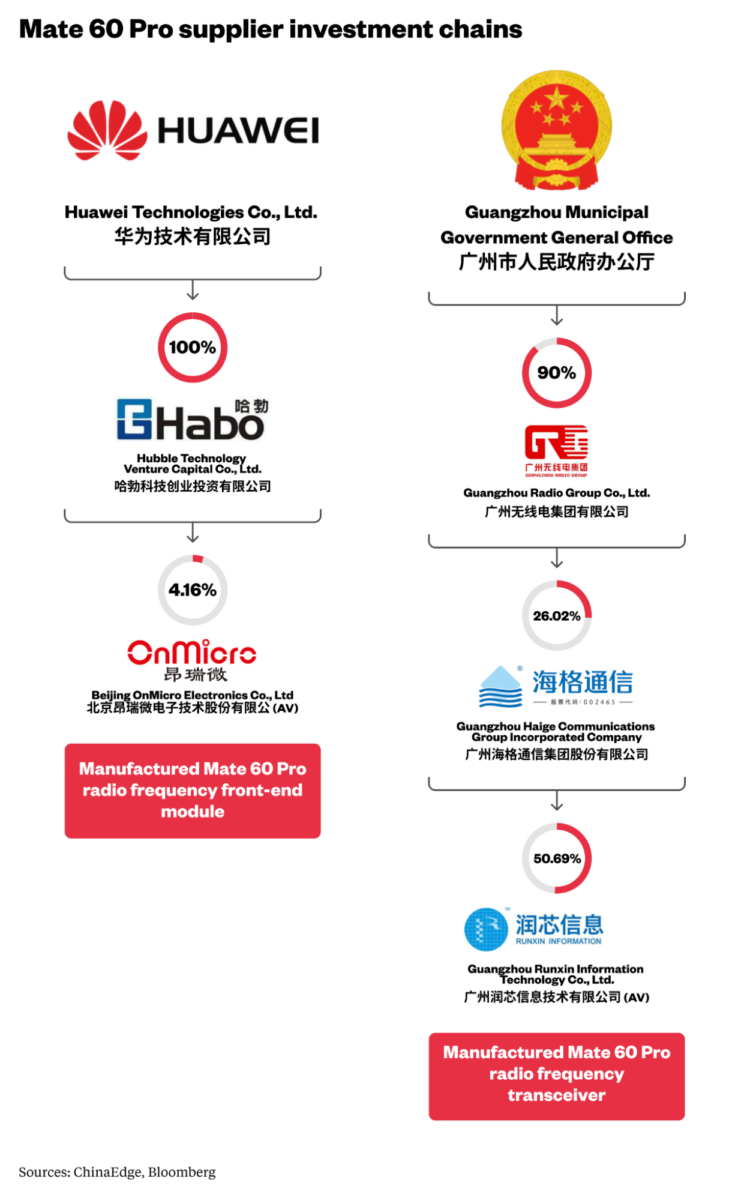

The Mate 60 Pro’s 5G-speed radio frequency front-end module, the part of the phone that receives and transmits radio signals, was manufactured by Chinese firm Beijing OnMicro Electronics Co., a company that has seen investment from Huawei-owned Hubble Technology Venture Capital.

The new phone’s radio frequency transceiver also was made domestically, as was its integrated circuit for power management, TechInsights Vice President Dan Hutcheson told The China Project.

“Huawei has significantly increased the share of ‘Made in China’ components in the Mate 60 Pro smartphone,” Hutcheson said. “Including [intellectual property] on the chips, an early estimate is about a 50% increase over previous smartphones.”

Established in 2019, Huawei’s Hubble Technology Venture Capital has invested in dozens of tech companies, many of which now are links in China’s semiconductor supply chain. Part of the benefit of investing in chip companies is that Huawei gets priority over other potential customers when it has an investment stake, one source told The Wall Street Journal last year.

Privately held Guangzhou Runxin Information Technology Co., Ltd., which has seen backing from entities invested in by the government of the city of Guangzhou, supplied Huawei with the Mate 60’s radio frequency transceiver, Bloomberg reported.

China’s central and local governments have overseen massive subsidies and investments in China’s chip companies. In 2022 alone, SMIC received 1.95 billion yuan ($267.2 million) in state subsidies.

“To some extent, Huawei’s ability to bring this phone to the market does signify that China’s subsidies are bearing fruit,” Hanna Dohmen, a research analyst at the Washington, D.C.–based Center for Security and Emerging Technology, said. “Huawei very likely would not have been able to do so without state-backed funding for SMIC.”

It’s still too early to say if China’s industrial policies aimed at Huawei’s consumer electronics business are an unqualified victory, however, said Dohmen, as the success of China’s industrial policies “depends on whether the costs of subsidies are worth the benefits achieved.”

Huawei, which manufactures telecommunications infrastructure equipment in addition to selling consumer electronics, faced a series of setbacks beginning in 2019 when the U.S. government placed it on a trade blacklist, accusing the Shenzhen-based firm of violating U.S. sanctions by doing business with Iran. Then, in 2020, Washington imposed new restrictions on the Chinese telecom giant, effectively barring any company in the world from selling Huawei any products that included any U.S.-made tech.

Huawei has faced criticism on various other fronts, including theft of intellectual property from U.S. firms, and inclusion of backdoor access to telecom equipment abroad that could be used for espionage. The U.S., Australia, the U.K., and other U.S.-aligned countries banned the use of Huawei’s 5G telecommunications infrastructure over espionage fears.

The Huawei Mate 40 smartphone, released in 2020, used radio frequency components from U.S. firm Qorvo and Japan’s Murata. The Huawei Mate 50 used a 4G Qualcomm chip after Qualcomm was granted a license by the U.S. government to supply Huawei with its less advanced chips. The U.S. government stopped granting export licenses to sell to Huawei in January 2023.

Huawei’s Mate 60 Pro still uses some products made outside China. The memory chips in the phone, stockpiled before Huawei was sanctioned in 2020, were made by South Korea’s SK Hynix.

Huawei declined to comment for this article, and SMIC, Hubble Technology, Beijing OnMicro, and Guangzhou Runxin didn’t respond to requests for comment.

A challenge for American policymakers

Huawei’s development of a more robust domestic supply chain makes it less vulnerable to threats of American measures meant to hobble it, giving U.S. policymakers less leverage over the company and fewer tools to restrict its activities in light of its various controversies.

Adding firms such as Guangzhou Runxin or Beijing OnMicro to the U.S. trade blacklist may not be the answer given the ease with which Chinese companies can evade such measures, Xiaomeng Lu, consulting firm Eurasia Group’s geo-technology practice director, said.

“There are a lot of work-arounds, whether it’s Huawei’s venture capital arm doing something, or a startup in China that we don’t know the name of,” Lu told The China Project. “It’s much harder for the U.S. government to identify those startups, and find out what they’re doing. They may only exist for a month, and then show up in a different office.”

Much of the U.S.-made equipment used for making chips, especially less advanced ones, is easily available for purchase online in small quantities, Lu said.

Critics of the American Huawei strategy have argued that the restrictions forced the Chinese company to innovate, shift its supply chains, and hurt American firms’ capacity to evolve and compete.

“The more we try to restrict them, the more they’re going to try to get around us,” TechInsights’ Hutcheson said. “It also takes the R&D dollars away from American, European, and Japanese companies, because they can’t sell there. The sanctions really do hurt you in the long term.”

“The nuclear option”

In a September 14 letter to the head of the U.S. Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security, tougher sanctions on SMIC and Huawei were proposed by a group of Congressional Republicans led by House Foreign Affairs Committee Chairman Mike McCaul (R-TX).

“U.S. Congressional China critics have called for essentially using a ‘nuclear option’ against both Huawei and SMIC,” Paul Triolo, technology policy lead at Dentons Global Advisors ASG, a Washington, D.C.–based consultancy, said.

The new measures would cut Huawei and SMIC off from the U.S. financial system and the banking systems of countries that usually comply with U.S. Treasury sanctions.

The proposed GOP move would affect the two Chinese firms by “complicating efforts to obtain components and equipment, and servicing for their existing equipment in the case of SMIC,” Triolo said.

Biden administration support for the proposed restrictions seems unlikely, as it could “scuttle the diplomatic thaw between the two countries and lead to significant Chinese retaliation against U.S. firms in China,” Triolo added.

Despite Congressional China hawks’ worries over Huawei’s progress and potential capacity for espionage, various analysts point out that it will be difficult for the company to keep moving up the value chain given current restrictions. Even producing the new Mate 60 Pro could be a challenge given that its memory chips were sourced from inventory, and producing replacement homegrown chips could prove costly.

U.S. Secretary of Commerce Gina Raimondo oversees some of the restrictions on SMIC and Huawei. Though the new phone’s release upset Raimondo’s visit to China in early September, it may be too early for Huawei to declare a decisive victory in the making of super speedy thin microchips.

“We don’t have any evidence that they can manufacture seven-nanometer at scale,” Raimondo said at a U.S. House hearing Tuesday, referring to the Mate 60’s Kirin 9000s processor.

Ramping up the restrictions on Chinese tech firms doesn’t just hurt the U.S. companies that sell to them, but could also have implications for the global economy if taken too far, said John Lee, the director of East-West Futures Consulting, where he focuses on China’s tech development.

“Serious technological containment of China means significant costs on the part of the U.S. and its allies, not to mention to the rest of the world that has to absorb the economic fallout, and the relevant cost-benefit debates have yet to play out,” said Lee.

No comments:

Post a Comment