Rose Khattar

This article recommends that Congress and the Biden administration center the needs of workers as they respond to the development and adoption of AI tools and systems. Specifically, they should be designing policy solutions that seek to maximize the benefit to workers from technological change, including steering the generation of AI to augment rather than automate workers; preparing workers to adjust to AI adoption; and meeting the needs of displaced workers, including by strengthening the unemployment insurance (UI) system and adopting a jobs guarantee.

Advanced AI has the capacity to change work

The scale or the way that advanced AI adoption in the workplace—such as generative AI tools and systems—will impact workers remains relatively unknown. Some potential effects could include replacing workers, complementing workers, freeing workers up to do more productive tasks, or creating new jobs. Because advanced AI is being deployed in enterprise technology, large firms are the most likely to be initial adopters of advanced AI tools and systems, meaning that a larger number of workers are likely to be generally affected. Goldman Sachs estimates that “roughly two-thirds of current jobs are exposed to some degree of AI automation, and that generative AI could substitute up to one-fourth of current work.” A study by McKinsey Global Institute estimates that 29.5 percent of all hours worked could be automated by 2030.

Regardless of the degree of impact, the adoption of AI in the workplace will likely be different from prior instances of technological disruption. Over the last few decades, technological change has largely impacted routine tasks that were mostly part of middle-wage jobs. In contrast, the adoption of AI is likely to impact a much wider degree of occupations, automating or augmenting nonroutine tasks that had not been impacted by past automation. Nonroutine tasks are mostly found in low-wage jobs, such as janitorial services, home health aides and food services, or in high-wage jobs, such as managerial roles and roles within the knowledge economy, posing a set of issues unlike before.

AI can also lead to job creation. A recent study has shown that firms investing in AI tend to “shift towards more educated workforces, with greater emphasis on STEM degrees.” Beyond increasing demand for some STEM skills, the adoption of AI is also likely to lead to increased demand for soft skills, particularly work that requires high emotional intelligence.

AI’s impact on women and Black and Latino workers

A key question for policymakers to explore is how the impact of the introduction of AI tools in workplaces will impact occupational segregation and gender, racial, and ethnic wage gaps. While some of the roles exposed to AI are female dominated—such as office and administrative support as well as community and social service sector jobs—other exposed roles, such as management, architecture, and engineering roles, are overrepresented by men, largely white men. At an aggregate level, women tend to be overrepresented in roles that are exposed to AI automation, with 79 percent of women employed in roles that could be affected, compared to 58 percent of men. In addition, Latino and Black workers are overexposed to automation in some roles, notably health care support roles, but underrepresented in other roles with high exposure, including architecture, engineering, and management occupations. On net, a recent study found that Latino and Black workers are concentrated in the occupations most susceptible to automation.

Increased demand for STEM skills also has clear equity implications: Women, Black, and Latino workers are vastly underrepresented in STEM education and its associated workforce, particularly within high-paid roles. Given this fact, AI could worsen existing occupational segregation and widen gender, racial, and ethnic wage gaps without a proactive approach to ensuring that jobs complemented or created by AI are available to a wide pool of workers. To do this, policymakers need to work to break down barriers to STEM educational attainment and workforce participation. Given the recent Supreme Court decision that limits colleges’ and universities’ ability to consider race in their admissions processes, it is doubly important. This includes partnering with HBCUs, Hispanic-Serving Institutions, Tribal Colleges and Universities, women’s colleges, and community colleges, ensuring the STEM industry is safe and free from harassment and improving funding for the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) and Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs (OFCCP) to ensure better enforcement of federal anti-discrimination and harassment laws.

Policy responses to the impact of the use of AI

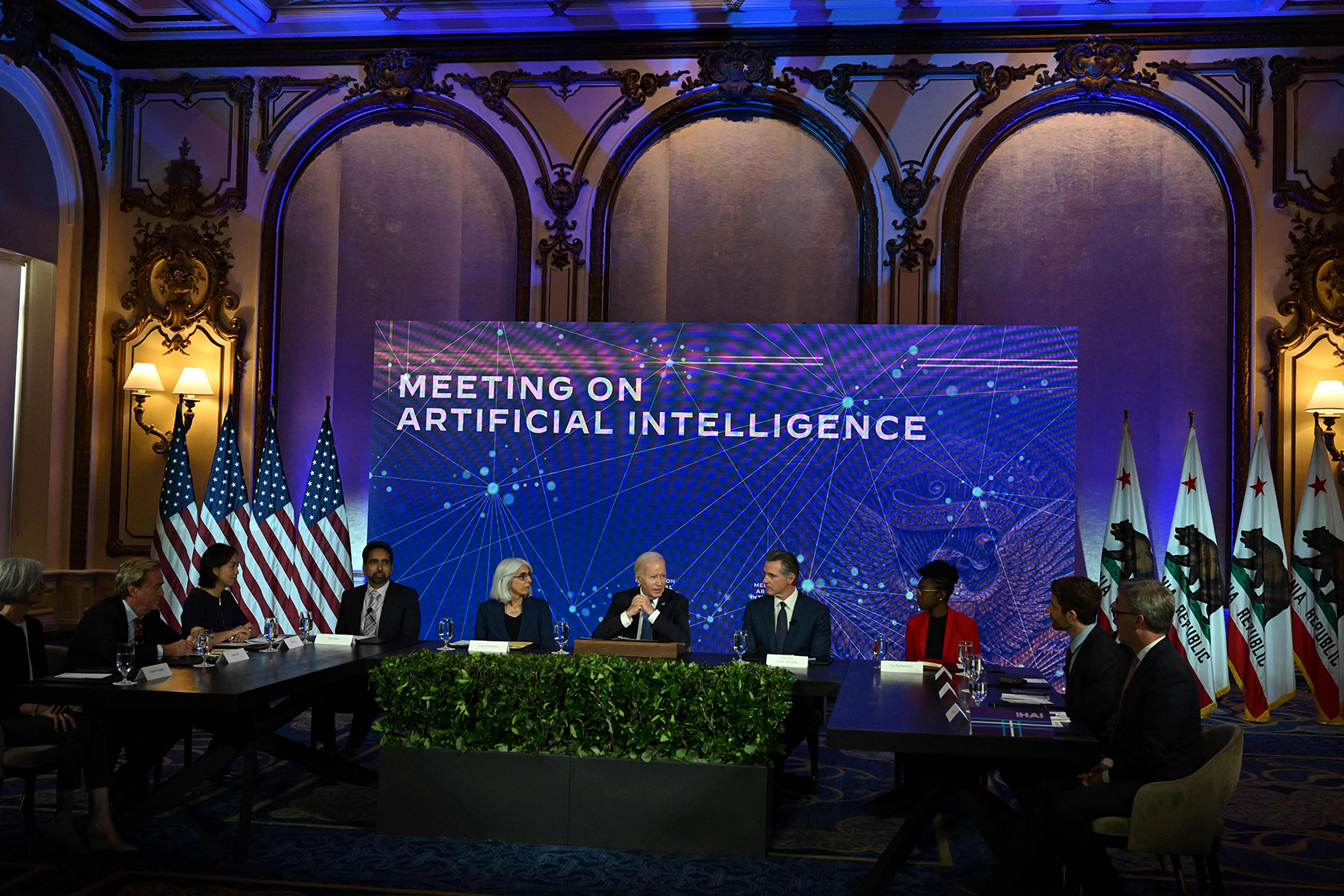

In their response to the design and deployment of AI tools and systems, the Biden administration—including through its National AI Strategy—and Congress must adopt a multifaceted, worker-centered approach to ensure workers share in the gains and that any harms are mitigated. This includes by steering the creation of AI to complement workers, preparing workers for the adoption of AI, and meeting the needs of displaced workers.

1. Steering the creation of AI to complement workers

AI does not have to replace workers and policymakers can work to steer AI policy in a manner to complement workers. Implementing stronger worker protections would bolster job security and job quality, especially if they were applicable beyond AI adoption. Such policies include: protecting workers through adopting EU-style laws limiting the ability of firms to lay off workers; banning certain uses and practices, including those that are discriminatory or violate worker privacy; helping workers better use collective bargaining, including sectoral bargaining; and encouraging worker involvement in the development of new technologies as technology increasingly disrupts industries.

2. Preparing workers for the adoption of AI

It is equally important policymakers invest in preparing workers for the adoption of AI by upskilling, reskilling, and retraining workers. Central to this is ensuring workers have access to paid, high-quality reskilling and retraining programs. This includes by adopting both active labor market policies, such as paid educational leave policies available in parts of the European Union, and labor management training partnerships, such as registered apprenticeships, which often help expand the pool of available workers in new roles to women and workers of color. Importantly, these approaches should be aimed at not just workers displaced from AI but also those who could be displaced by ensuring they are ready for the impacts of technological disruption on work. Moreover, it is equally important that workers benefit financially from the adoption of AI. This includes ensuring jobs created by AI are good jobs, with collective bargaining rights, and adopting worker ownership shares.

3. Meeting the needs of displaced workers

Some workers will be displaced by AI and policymakers must be focused on addressing their needs. Long-overdue enhancements to the social safety net must be pursued for those who lose their jobs to AI and are unable to find work. For example, Congress must modernize UI through expanding eligibility to those currently not eligible (such as independent contractors); increasing benefit levels; and significantly expanding time allowed on UI to allow for retraining. This would be similar to measures adopted during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, which helped the country weather a significant external shock and prevented a downward spiral of unemployment and economic depression. Additionally, UI could be further improved to allow the collection of UI by individuals who haven’t yet been laid off but are in vulnerable occupations or sectors for income during retraining via a jobseeker’s allowance.

Beyond reforms to the safety net, actively working to ensure displaced workers find work is critical. Central to this is adopting a job guarantee to help ensure workers are able to find employment. In addition, helping displaced workers gain in-demand skills requires policymakers to invest in retraining programs that allow people to get paid during retraining, including adopting a similar—though more robust—model to the Department of Labor’s Trade Adjustment Assistance but with a focus on job loss due to technological disruption. In addition, improved retraining interventions must be targeted at highly trained occupations that may also be displaced. This should be focused upon how to best leverage their skills in other related occupations that are less susceptible to AI displacement.

Conclusion

While technological disruption has long been associated with a doom-and-gloom narrative of “robots taking jobs” and mass unemployment that has not been realized, the potential impacts of AI on the labor market could be different from the past. On the one hand, the adoption of AI could create new jobs, complement existing work, raise worker productivity, lift wages, boost economic growth, and increase living standards. On the other hand, AI could displace workers, erode job quality, increase unemployment, and exacerbate inequities. Whether and how AI benefits or harms workers is not a foregone conclusion—it is up to the Biden administration and Congress to guide the users and adopters of AI in the right direction.

No comments:

Post a Comment