KYLE MIZOKAM

The South China Sea, famous for its commerce, abundant fishing grounds, and massive oil and natural gas reservoirs, is now known as something else entirely: a chessboard for the struggle between the United States and China.

China’s military expansion into the sea is taking place at the expense of regional neighbors whose competing territorial claims are being ignored. Into this volatile mix comes the U.S., which is supporting longstanding allies and international rules of law.

1.35 Million Square Miles

The South China Sea is tricky to define by location. The sea is off the coast of Vietnam but also off the coast of China, the Philippines, Brunei, Malaysia, and Taiwan. That’s the defining geographic feature of the sea, that its border is shared by many countries—and also the problem.

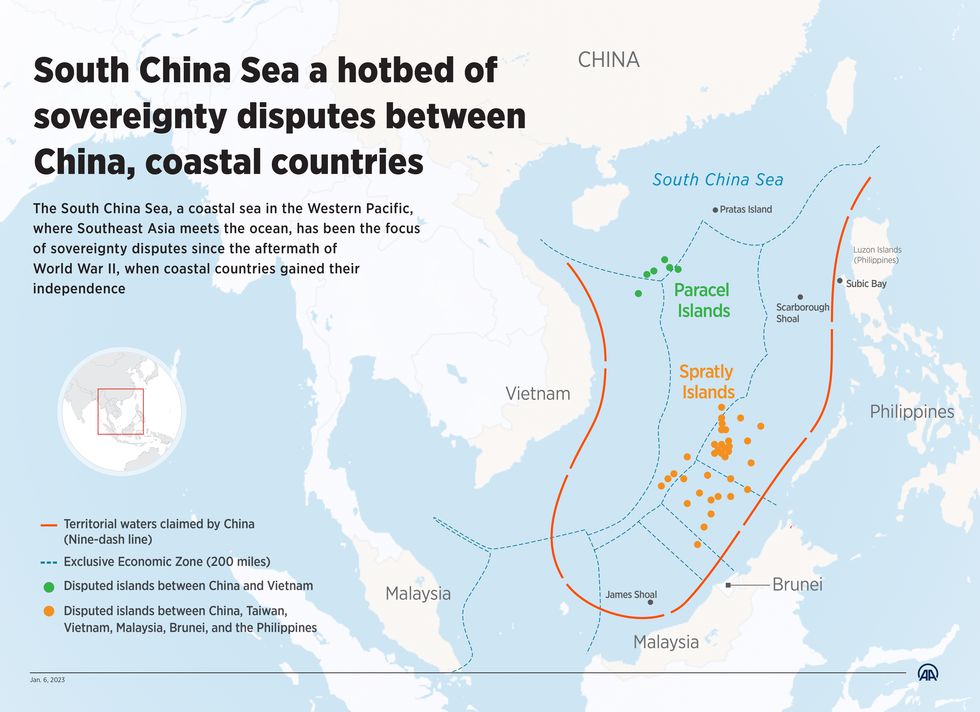

Various parts of the sea are claimed by all six countries, many of which also claim the islets, shoals, and reefs peppering the region. The two main islet groups are the Spratly Islands—the eastern grouping nearest to the Philippines, Malaysia, and Brunei—and the Paracel Islands, northwest of the Spratlys and closer to Vietnam, China, and Taiwan.

In recent years, none of the countries pushed their territorial claims in the South China Sea—that is, until China decided to. Unlike most countries in the region, which typically claim just a corner of the 1.35-million-square-mile sea, China claims 90 percent of it. And it has pushed its neighbors out much more aggressively than any other country in decades.

Fake Islands, Court Rulings, and Lasers

One problem is that territorial claims in the South China Sea are typically centered on land features. All countries have a right to claim territorial waters up to 12 nautical miles from land masses and claim exclusive economic development rights up to 200 miles from land. The South China Sea, however, is bereft of islands of any real significance, with most qualifying, at best, as atolls, islets, and shoals. These sorts of minor land features, some of which lose a significant amount of area at high tide, are not to be used to extend a country’s territory by international law.

That’s proven no big obstacle to China, which starting in the early 2010s moved dredging equipment into the sea, building up several of the minor land features into full-fledged islands. Using nearby seabed, places like Mischief Reef (legally a low-tide elevation), Fiery Cross Reef (legally a rock), and Woody Island (legally a rock/island). The construction of the islands, and the subsequent construction of buildings on the islands, were claimed by Beijing to be scientific research outposts. In 2016, Taiwan announced that the Chinese outpost on Woody Island was armed with surface-to-air missiles, the first of several discoveries of military equipment in the region.

In 2016, an international court of law in The Hague, the Netherlands, ruled that China’s vast territorial claims in the South China Sea had no basis in international law and were invalid. China angrily denounced the verdict, which carried no legal penalty.

American, Australian, Canadian, and other outside military forces have also sailed and flown through the region and near the Chinese “islands.” The sorties, known as “freedom of navigation operations,” or FONOPS, are meant to assert the right of any vessel, including foreign military vessels, to sail in an area illegally claimed by another country. China’s response to these ships and aircraft have run from relatively benign shadowing of warships by Chinese Navy ships to the use of lasers to harass and potentially blind aircraft pilots.

The Potential For War

China is in the midst of an unprecedented military expansion. Its Navy outnumbers the U.S. Navy in numbers of ships, and its armed forces are more powerful than all of the rest of the claimants in the South China Sea combined. Individually, none of these countries can oppose China’s expansion in the region.

None of this is all that new. Expanding powers have built empires at the expense of weaker states for thousands of years. In his History of the Peloponnesian War, the Greek historian Thucydides wrote,“The strong do what they can, the weak suffer what they must.”

In this situation, the weak have allies in the form of a loose coalition of western countries, including the United States, Australia, Canada, and the United Kingdom, plus nearby Japan and India. These countries want the existing rules-based international order to continue, for economic and political reasons, and are broadly in agreement with the international court ruling against China. If China pushes its neighbors too far, that could well draw in the United States and others, sparking a larger regional conflict—what some might even call World War III.

China has pushed back, claiming that that a coalition of foreign countries conspires to hem China in and isolate it. That’s not true: none of these countries, all of whom assisted China’s rise over the past 35 years, have an issue with China becoming an economically, politically, and militarily powerful country. The issue is with what China has done since it became powerful.

No comments:

Post a Comment